Buy voltarol 100mg on line

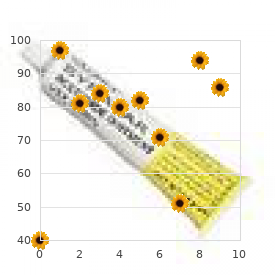

In intubated infants medications ending in pam buy voltarol 100 mg mastercard, tracheal aspirate smears may indicate the presence of inflammatory cells, and cultures may provide information about organisms colonizing the trachea. Because the microbiology of pneumonia in the newborn is the same as that of sepsis, the guidelines for management discussed in Chapter 6 are applicable. Initial antimicrobial therapy should include a penicillin (usually ampicillin) or a penicillinase-resistant penicillin (if staphylococcal infection is a possibility) and an aminoglycoside or a third-generation cephalosporin. The oxazolidinone antibiotic linezolid, an agent with a unique mechanism of action with activity against gram-positive organisms, has been studied in neonates. Sixty-three neonates with known or suspected resistant gram-positive infections were randomly assigned to receive linezolid or vancomycin. No difference in efficacy of the two agents was noted, and the authors concluded that linezolid is a safe and effective alternative to vancomycin in treatment of resistant gram-positive infections. Until techniques are developed that can distinguish infectious from noninfectious causes of respiratory distress syndrome, it is reasonable to treat all infants who present with clinical and radiologic signs of the syndrome. Therapy is instituted for sepsis, as outlined earlier, after appropriate cultures have been taken. If the results of cultures are negative and the clinical course subsequently indicates that the illness was not infectious, the antimicrobial regimen is stopped. Antibiotics are only part of the management of the newborn with pneumonia; supportive measures, such as maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, providing oxygen or support of respiration with continuous positive airway pressure, or instituting intubation and ventilation, are equally important. Drainage of pleural effusions may be necessary when accumulation of fluid results in respiratory embarrassment. Single or multiple thoracocenteses may be adequate when the volumes of fluid are small. If larger amounts are present, a closed drainage system with a chest tube may be needed. The tube should be removed as soon as its drainage function is completed because delay may result in injury to local tissues, secondary infection, and sinus formation. Empyema and abscess formation are uncommon but serious complications of pneumonia. Even autopsy studies are equivocal in determining the importance of pneumonia because respiratory disease may have been the cause of death, a contributing factor in death, or incidental to and apart from the main cause of death. Ahvenainen156 noted that pneumonia often is a fatal complicating factor in infants with certain underlying conditions, such as central nervous system malformations or disease, congenital heart disease, and anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract such as intestinal atresia. A prospective study of premature newborns found ventilator-associated pneumonia to occur frequently and to be significantly associated with death in extremely premature infants who remained in a neonatal intensive care unit for more than 30 days. Brasfield and colleagues243 studied a group of 205 infants hospitalized with pneumonitis during the first 3 months of life and identified radiographic and pulmonary function abnormalities that persisted for more than 1 year. Clark H, Barysh N: Retropharyngeal abscess in an infant of six weeks, complicated by pneumonia and osteomyelitis, with recovery: report of case, Arch Pediatr 53:417, 1936. Ravindra C, Merchant R, Dalal S, et al: Retropharyngeal abscesses in infants, Indian J Pediatr 50:449, 1983. Masaaki H, Hisashi I, Kyoko T: Retropharyngeal abscess in a 2-month-old infant-a case report, Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (Tokyo) 75:651, 2003. Falup-Pecurariu O, Leibovitz E, Pascu C, Falup-Pecurariu C: 2009 Bacteremic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus deep neck abscess in a newborn-case report and review of literature, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 73, 1824. Coulthard M, Isaacs D: Neonatal retropharyngeal abscess, Pediatr Infect Dis J 10:547, 1991. Young N, Finn A, Powell C: Group B streptococcal epiglottitis, Pediatr Infect Dis J 15:95, 1996. Durbaca S: Antitetanus and antidiphtheria immunity in newborns, Rom Arch Microbiol Immunol 58:267, 1999. Vahlquist B: the transfer of antibodies from mother to offspring, Adv Pediatr 10:305, 1958. Galazka A: the changing epidemiology of diphtheria in the vaccine era, J Infect Dis 181(Suppl 1):S2, 2000. Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, et al: Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children, J Infect Dis 175:1440, 1997. Edelman K, Nikkari S, Ruuskanen O, et al: Detection of Bordetella pertussis by polymerase chain reaction and culture in the nasopharynx of erythromycin-treated infants with pertussis, Pediatr Infect Dis J 15:54, 1996. Schaefer O: Otitis media and bottle feeding: an epidemiological study of infant feeding habits and incidence of recurrent and chronic middle ear disease in Canadian Eskimos, Can J Public Health 62:478, 1971. Turner D, Leibovitz E, Aran A, Piglansky L, et al: Acute otitis media in infants younger than two months of age: microbiology, clinical presentation and therapeutic approach, Pediatr Infect Dis J 21:669, 2002. Pestalozza G, Cusmano G: Evaluation of tympanometry in diagnosis and treatment of otitis media of the newborn and of the infant, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2:73, 1980. Meyer K, Girgis N, McGravey V: Adenovirus associated with congenital pleural effusion, J Pediatr 107:433, 1985. Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Kassis I, Bamberger E, et al: Fatal hospitalacquired Legionella pneumonia in a neonate, Pediatr Infect Dis J 29:280, 2010. Barter R: the histopathology of congenital pneumonia: a clinical and experimental study, J Pathol Bacteriol 66:407, 1953. Bernstein J, Wang J: the pathology of neonatal pneumonia, Am J Dis Child 101:350, 1961. In Charles D, Finland M, editors: Obstetric and perinatal infections, Philadelphia, 1973, Lea & Febiger, p 122. Jialin Y, Boman C, Guanxin L, Linyan H, Luquan L: Electron microscopic analysis of bacterial biofilm on tracheal tubes removed from intubated neonates and the relationship between bacterial biofilm and lower respiratory infections, Pediatrics 121:S121, 2008. In de Louvois J, Harvey D, editors: Infection in the newborn, New York, 1990, John Wiley, p 13. Ohlsson A, Bailey T: Neonatal pneumonia caused by Branhamella catarrhalis, Scand J Infect Dis 17:225, 1985. Andersson S, Larinkari U, Vartia T: Fatal congenital pneumonia caused by cat-derived Pasteurella multocida, Pediatr Infect Dis J 13:74, 1994. Brook I: Microbiology of empyema in children and adolescents, Pediatrics 85:722, 1990. Shamir R, Horev G, Merlob P, et al: Citrobacter diversus lung abscess in a preterm infant, Pediatr Infect Dis. Greenough A: Gains and losses from dexamethasone for neonatal chronic lung disease, Lancet 352:835, 1998. Onland W, Offringa M, van Kaam A: Late (7 days) inhalation corticosteroids to reduce bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Whitelaw A, Evans A, Corrin B: Immotile cilia syndrome: a new cause of neonatal respiratory distress, Arch Dis Child 56:432, 1981. Ramet J, Byloos J, Delree M, et al: Neonatal diagnosis of the immotile cilia syndrome, Chest 89:138, 1986. Ciliary dyskinesia and ultrastructural abnormalities in respiratory disease: Lancet 1:1370, 1988. Hjalmarson O: Epidemiology of classification of acute, neonatal respiratory disorders: a prospective study, Acta Paediatr Scand 70:773, 1981. In British Perinatal Mortality Survey, second report: perinatal problems, Edinburgh, 1969, Livingstone, p 184. Apisarnthanarak A, Holzmann-Pazgal G, Hamvas A, et al: Ventilator-associated pneumonia in extremely preterm neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit: characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes, Pediatrics 12:1283, 2003. Pacifico L, Panero A, Roggini M, et al: Ureaplasma urealyticum and pulmonary outcome in a neonatal intensive care population, Pediatr Infect Dis J 16:579, 1997. Thaarup J, Ellermann-Eriksen S, Sternholm J: Neonatal pleural empyema with group A Streptococcus, Acta Paediatr 86:769, 1997. World Health Organization: Acute respiratory infections in children: case management in small hospitals in developing countries, Geneva, 1990, World Health Organization. Soofi S, Ahmed S: 2012 Effectiveness of community based management of severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children aged 2-59 months in Matiari District, rural Pakistan: a cluster- randomized controlled trial, Lancet 379:729, 2012. Petersen S, Astvad K: Pleural empyema in a newborn infant, Acta Paediatr Scand 65:527, 1976. During the worldwide pandemic of staphylococcal disease from the early 1950s to the early 1960s, pediatric centers in Europe,1-5 Australia,6 and North America6-11 reported the infrequent occurrence of neonatal osteomyelitis, accounting for only one or two admissions per year at each institution. Nelson, personal communication, 1987) during the decade 1970 to 1979 indicated little or no change in the incidence of this condition.

Buy cheap voltarol 100 mg on line

Ludwicka A medications 5 songs 100mg voltarol, Locci R, Jansen B, et al: Microbial colonization of prosthetic devices. Attachment of coagulase-negative staphylococci and "slime"-production on chemically pure synthetic polymers, Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B 177:527-532, 1983. Gristina A: Biomaterial-centered infection: microbial adhesion versus tissue integration, Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004:4-12, 1987. In vitro and in vivo studies with emphasis on staphylococcal-leukocyte interaction, J Clin Invest 55:561-566, 1975. Gusarov I, Shatalin K, Starodubtseva M, et al: Endogenous nitric oxide protects bacteria against a wide spectrum of antibiotics, Science 325:1380-1384, 2009. Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J: Alpha-toxin of Staphylococcus aureus, Microbiol Rev 55:733-751, 1991. Suttorp N, Fuhrmann M, Tannert-Otto S, et al: Pore-forming bacterial toxins potently induce release of nitric oxide in porcine endothelial cells, J Exp Med 178:337-341, 1993. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Schneewind O: Vaccine protection against Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, J Exp Med 205:287-294, 2008. Kaneko J, Kamio Y: Bacterial two-component and hetero-heptameric pore-forming cytolytic toxins: structures, pore-forming mechanism, and organization of the genes, Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:9811003, 2004. Heilman C, Hussain M, Peters G, et al: Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystrene surface, Mol Microbiol 24:1013-1024, 1997. Hussain M, Heilman C, Peters G, et al: Teichoic acid enhances adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis to immobilized fibronectin, Microb Pathog 31:261-270, 2001. Mack D, Nedelmann M, Krokotsch A, et al: Characterization of transposon mutants of biofilm-producing Staphylococcus epidermidis impaired in the accumulative phase of biofilm production: genetic identification of a hexosamine-containing polysaccharide intercellular adhesion, Infect Immun 62:3244-3253, 1994. McKenney D, Hubner J, Muller E, et al: the ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/ adhesin, Infect Immun 66:4711-4720, 1998. Hussain M, Herrmann M, von Eiff C, et al: A 140-kilodalton extracellular protein is essential for the accumulation of s Staphylococcus epidermidis strains on surfaces, Infect Immun 65:519-524, 1997. Kocianova S, Vuong C, Yao Y, et al: Key role of poly-gamma-dlglutamic acid in immune evasion and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis, J Clin Invest 115:688-694, 2005. Ohara-Nemoto Y, Ikeda Y, Kobayashi M, et al: Characterization and molecular cloning of a glutamyl endopeptidase from Staphylococcus epidermidis, Microb Pathog 33:33-41, 2002. Gessler P, Nebe T, Birle A, et al: Neutrophil respiratory burst in term and preterm neonates without signs of infection and in those with increased levels of C-reactive protein, Pediatr Res 39:843-848, 1996. Strunk T, Prosser A, Levy O, et al: Responsiveness of human monocytes to the commensal bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis develops late in gestation, Pediatr Res 72:10-18, 2012. Marrach P, Kappler J: the staphylococcal enterotoxin and their relatives, Science 248:705-711, 1990. Isaacs D, Fraser S, Hogg G, et al: Staphylococcus aureus infections in Australasian neonatal nurseries, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 89:F331-F335, 2004. Powell C, Bubb S, Clark J: Toxic shock syndrome in a neonate, Pediatr Infect Dis J 26:759-760, 2007. Takahashi N, Uehara R, Nishida H, et al: Clinical features of neonatal toxic shock syndrome-like exanthematous disease emerging in Japan, J Infect 59:194-200, 2009. Kikuchi K, Takahashi N, Piao C, et al: Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains causing neonatal toxic shock syndrome-like exanthematous disease in neonatal and perinatal wards, J Clin Microbiol 41:3001-3006, 2003. Takahashi N, Nishida H, Kato H, et al: Exanthematous disease induced by toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 in the early neonatal period, Lancet 351:1614-1619, 1998. Linder N, Hernandez A, Amit L, et al: Persistent coagulase-negative staphylococci bacteremia in very-low-birth-weight infants, Eur J Pediatr 170:989-995, 2011. Regev-Yochay G, Rubinstein E, Barzilai A, et al: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in neonatal intensive care unit, Emerg Infect Dis 11:453-456, 2005. Khashu M, Osiovich H, Henry D, et al: Persistent bacteremia and severe thrombocytopenia caused by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus in a neonatal intensive care unit, Pediatrics 117:340-348, 2006. Kuint J, Barzilai A, Regev-Yochay G, et al: Comparison of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia to other staphylococcal species in a neonatal intensive care unit, Eur J Pediatr 166:319-325, 2007. Hira V, Sluijter M, Estevao S, et al: Clinical and molecular epidemiologic characteristics of coagulase-negative staphylococcal bloodstream infections in intensive care neonates, Pediatr Infect Dis J 26:607-612, 2007. Isaacs D: A ten year, multicentre study of coagulase negative staphylococcal infections in Australasian neonatal units, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88:F89-F93, 2003. Falup-Pecurariu O, Leibovitz E, Pascu C, et al: Bacteremic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus deep neck abscess in a newborn- case report and review of literature, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 73:1824-1827, 2009. Mutlu M, Dereci S, Aslan Y: Deep neck abscess in neonatal period: case report and review of literature, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78:577-582, 2014. Spiegel R, Miron D, Sakran W, et al: Acute neonatal suppurative parotitis: case reports and review, Pediatr Infect Dis J 23:76-78, 2004. Bodemer C, Panhans A, Chretien-Marquet B, et al: Staphylococcal necrotizing fasciitis in the mammary region in childhood: a report of five cases, J Pediatr 131:466-469, 1997. Kapoor V, Travadi J, Braye S: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely premature neonate: a case report with a brief review of literature, J Paediatr Child Health 44:374-376, 2008. Peters B, Hentschel J, Mau H, et al: Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome complicating wound infection in a preterm infant with postoperative chylothorax, J Clin Microbiol 36:3057-3059, 1998. Farroha A, Frew Q, Jabir S, et al: Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome due to burn wound infection, Ann Burns Fire Disasters 25:140-142, 2012. Drinkovic D, Pottumarthy S, Knight D, et al: Neonatal coagulasenegative staphylococcal meningitis: a report of two cases, Pathology 34:586-588, 2002. Bauer F, Huttova M, Rudinsky B, et al: Nosocomial meningitis caused by Staphylococcus other than S. Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P: Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection: risk factors and long-term follow-up, Childs Nerv Syst 22:692-697, 2006. Reinprecht A, Dietrich W, Berger A, et al: Posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus in preterm infants: long-term follow-up and shunt-related complications, Childs Nerv Syst 17:663-669, 2001. Filka J, Huttova M, Tuharsky J, et al: Nosocomial meningitis in children after ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion, Acta Paediatr 88:576-578, 1999. Sherwin C, Broadbent R, Young S, et al: Utility of interleukin-12 and interleukin-10 in comparison with other cytokines and acute-phase reactants in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis, Am J Perinatol 25:629636, 2008. Plan O, Cambonie G, Barbotte E, et al: Continuous-infusion vancomycin therapy for preterm neonates with suspected or documented gram-positive infections: a new dosage schedule, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93:F418-F421, 2008. Jacqz-Aigrain E, Zhao W, Sharland M, et al: Use of antibacterial agents in the neonate: 50 years of experience with vancomycin administration, Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 18:28-34, 2013. Dotis J, Iosifidis E, Ioannidou M, et al: Use of linezolid in pediatrics: a critical review, Int J Infect Dis 14:e638-e648, 2010. Bergdahl S, Ekengren K, Eriksson M: Neonatal hematogenous osteomyelitis: risk factors for long-term sequelae, J Pediatr Orthop 5:564568, 1985. Wong M, Isaacs D, Howman-Giles R, et al: Clinical and diagnostic features of osteomyelitis occurring in the first three months of life, Pediatr Infect Dis J 14:1047-1053, 1995. Korakaki E, Aligizakis A, Manoura A, et al: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis and septic arthritis in neonates: diagnosis and management, Jpn J Infect Dis 60:129-131, 2007. Waseem M, Devas G, Laureta E: A neonate with asymmetric arm movements, Pediatr Emerg Care 25:98-99, 2009. Parmar J: Case report: septic arthritis of the temporomandibular joint in a neonate, Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46:505-506, 2008. Yuksel S, Yuksel G, Oncel S, et al: Osteomyelitis of the calcaneus in the newborn: an ongoing complication of guthrie test, Eur J Pediatr 166:503-504, 2007. Barrie D: Staphylococcal colonization of the rectum in the newborn, Br Med J 1:1574-1576, 1966. Soeorg H, Huik K, Parm U, et al: Genetic relatedness of coagulasenegative staphylococci from gastrointestinal tract and blood of preterm neonates with late-onset sepsis, Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:389-393, 2013. Masunaga K, Mazaki R, Endo A, et al: Colonic stenosis after severe methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus enterocolitis in a newborn, Pediatr Infect Dis J 18:169-171, 1999. The hospital infection control practices advisory committee, Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 17:53-80, 1996.

Discount voltarol 100mg on-line

In addition schedule 8 medications victoria order voltarol online pills, postslaughter treatments, including heating and freezing, play an important role. Findings on the isolation of parasites from various food animals in the United States were reviewed by Hill and Dubey. Analysis of the hearts from 383 lambs that were raised in the United States and butchered in commercial abattoirs for human consumption found that greater than 27% were seropositive, and viable cysts were isolated from 78% of the positive animals. The consumption of undercooked mutton or lamb was found to be associated with acute infection in pregnant European women: in France,340 where it is traditionally considered to be an important source of infection, but also in Norway,315 in a study in five European countries,316 and it was also involved in several outbreaks. Toxoplasma gondii infection is also common in goats, and prevalence rates reached 75% in some surveys. High rates were reported in the United States for white-tailed deer (30%65%), wild boars (up to 37%), and bears (75%-85%). Raw eggs from hens raised in contemporary high-density production facilities are unlikely to transmit Toxoplasma infection,326 but caution is probably warranted for eggs from free-range hens, although any cooking will kill the parasite. Epidemiologic studies have provided indirect evidence that this route contributes to a large proportion of human infections in South America and Africa and, to a lesser extent, in Asia. Recent findings suggested that it may also play a predominant role in developed countries. A new test has been developed that enables the recognition in serum samples of antibody responses to an 11-kDa sporozoite protein, which indicate that infection was acquired by the ingestion of oocysts within the previous 6 to 8 months. Cats usually become infected soon after they begin to hunt and ingest contaminated prey, and oocysts in their environment are less pathogenic than viable cysts in infected prey. Shedding of oocysts in the feces begins on average 3 to 5 days after initial infection and lasts for up to 21 days, with a median of 8 days. After this short period, cats are unlikely to shed oocysts again in their lifetime. Given their grooming habits, adult cats do not carry oocysts in their fur,32 and cat bites or scratches are not considered to be risk factors for Toxo plasma infection. Of five European case-control studies that investigated a possible association between cat ownership and acute infections in pregnancy, only one identified cleaning the litter box as a significant risk factor,315 although an association between cat ownership and past Toxoplasma infection was found in several seroprevalence surveys. The significance of these findings is difficult to determine because, in most studies, other factors were also detected that indirectly result from the presence of cats at or close to the home, such as contact with the soil, which might be the true risk factor. The burden of oocysts has been demonstrated to be very high20,286,318 as a consequence of two factors. The first is the remarkable stability of oocysts, which may remain viable for more than 1 year in the soil, especially when they are deposited at moist, temperate, and shady locations. In a review, Jones and Dubey20 found that the seroprevalence in domestics cats worldwide varied from 2% in China to 89% in South America. Variations exist within countries and within cities because of the influences of lifestyle and age. Oocysts were found to be widely distributed in rural376 as well as residential urban377,378 areas. High densities were reported around elementary schools,379 sandpits, and playgrounds,380 which are favorite defecation sites for cats. Standard municipal systems in developed countries should be able to filter oocysts, but small or malfunctioning systems could fail to do so. Contaminated drinking water has been implicated in several outbreaks,20 and consistent evidence from several epidemiologic surveys has shown that contaminated drinking water also causes endemic Toxoplasma infection. Drinking untreated lake and river water was identified as a risk factor in a survey that compared seropositivity rates among military personnel involved in jungle operations and urban soldiers in Colombia. In solid-organ transplantations, infection results from the transmission of the parasite via the transplanted organ from an infected donor to an uninfected recipient. This risk is highest for heart transplants and is significantly lower for other solid organs. In hematopoietic stem cell transplants, complications result mainly from the reactivation of a preexisting latent infection under intense suppressive therapy. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients are exposed to a much higher risk than those receiving autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Tachyzoites have also been transmitted via blood products, in particular those containing the white cell fraction, and by accidental injection in the laboratory. Results from one retrospective study involving patient cohorts in France supported the notion that treatment of congenitally infected infants should be continued for 12 or more months to avert late clinical manifestations of disease and recurrences, although changes in specific antibody titers did not differ, depending on duration of treatment. Pyrimethamine dosages of 1 mg/kg of body weight/day yield serum drug levels of approximately 1000 to 2000 ng/mL 4 hours after the administration of the drug. When the same dose is administered on alternate days three times per week, serum levels of approximately 500 ng/mL are attained 4 hours after the each dose. The inhibitory and the parasiticidal concentrations of these drugs depend upon the nature of the assay and the calibration systems, as well as upon the strain of the parasite. Although several triple therapies have been shown to afford some benefits, they are not generally advocated for routine clinical use because the number of tablets that would need to be swallowed would be increased to an unpalatable level (7-8 times per day). To date, pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine is the most widely applied therapy and is generally well tolerated, whereas the combination of pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine is also used outside of the United States. Compared with sulfadiazine or sulfadoxine, other tested sulfonamides, namely, sulfapyrazine, sulfamethazine, sulfamerazine, sulfathiazole, sulfapyridine, sulfadimidine, and sulfisoxazole, have not been found to confer any benefits and are, moreover, not so universally available. Of note, levels of pyrimethamine achieved in infants being treated for overt congenital toxoplasmosis can vary by factors of 8- to 25-fold, and those of sulfonamides between 4and 5-fold. The lack of commercially available suspensions of pyrimethamine and sulfonamide, specifically for pediatric use, exacerbates the problem of defining suitable doses for infants. A regimen of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and spiramycin was used in the past but is not currently used extensively in France. An alternative regimen of pyrimethamine in combination with sulfadoxine, marketed commercially as Fansidar, is used by some groups outside of the United States. Because sulfadoxine has a much longer half-life than sulfadiazine, this combination is typically administered orally every 10 days for 1 year at doses of 1. Outside of the United States, Fansidar is available as syrup, which simplifies administration. In our experience, this regimen is well tolerated and seldom leads to relevant neutropenia405; regular hematologic testing is nevertheless needed as with the standard pyrimethamine/sulfadiazine treatment regimen (see later). In a small cohort study, Fansidar has also been used to treat pregnant women in whom fetal infection was confirmed using a dosage of 25 mg of pyrimethamine and 500 mg of sulfadoxine per 20 kg of body weight and 50 mg of folinic acid on a twice-monthly basis. Under steady-state conditions, the ratio of fetal-to-maternal drug concentrations in umbilical vein blood at the time of delivery ranged from 0. After birth, the combination was continued, with the dose adjusted to the weight of the infant. Because pyrimethamine inhibits the activity of dihydrofolate reductase, a precursor of folic acid, it induces, as expected, a reversible and usually gradual suppression of hematopoiesis. Neutropenia is the most severe and common side effect of treatment with pyrimethamine, although reduced platelet counts and anemia are not uncommon. When the drugs are administered at the recommended doses, their plasma concentrations usually fall within the expected therapeutic limits, and the intervention is generally well tolerated (in 86% of cases). Available data afford no evidence of teratogenicity when administered in the recommended dosage,474,475 but pyrimethamine/sulfonamides should not be given in the first 14 weeks of gestation in any case. Because the toxic effects of pyrimethamine on hematopoiesis are a consequence of the induced deficiency in folic acid, which is required for cell division, this problem can be ameliorated by the co-administration of folinic acid (leucovorin). Leucovorin calcium is usually administered three times per week at a dose of 5 to 20 mg, with which regimen the inhibitory action of pyrimethamine on the proliferation of T. In rare cases, the latter can lead to severe or even fatal allergic dermatitis (Stevens-Johnson and Luell syndromes). During this phase, spiramycin can clear the parasite from the blood and reduce the frequency of placental infection. The infectious load of the placenta is also reduced, although, to attain this effect, a longer treatment duration is necessary than is required with a pyrimethamine/sulfonamide regimen.

Cheap 100mg voltarol with amex

Other diagnostic considerations in neonates include infection with parainfluenza viruses and coxsackieviruses holistic medicine 100 mg voltarol for sale, drug-induced parotitis, and facial cellulitis. In addition to these conditions in neonates, the differential diagnosis in pregnant women includes anterior cervical lymphadenitis, idiopathic recurrent parotitis, salivary gland calculus with obstruction, sarcoidosis with uveoparotid fever, and salivary gland tumors. Other entities should be considered when the manifestations appear in organs other than the parotid. Testicular torsion in infancy may produce a painful scrotal mass resembling mumps orchitis. Williams V, Gershon A, Brunell P: Serologic response to varicellazoster membrane antigens measured by indirect immunofluorescence, J Infect Dis 130:669, 1974. Zaia J, Oxman M: Antibody to varicella-zoster virus-induced membrane antigen: immunofluorescence assay using monodisperse glutaraldehyde-fixed target cells, J Infect Dis 136:519, 1977. Forghani B, Schmidt N, Dennis J: Antibody assays for varicella-zoster virus: comparison of enzyme immunoassay with neutralization, immune adherence hemagglutination, and complement fixation, J Clin Microbiol 8:545, 1978. LaRussa P, Steinberg S, Waithe E, et al: Comparison of five assays for antibody to varicella-zoster virus and the fluorescent-antibodyto-membrane-antigen test, J Clin Microbiol 25:2059, 1987. Shehab Z, Brunell P: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for susceptibility to varicella, J Infect Dis 148:472, 1983. Gershon A, Kalter Z, Steinberg S: Detection of antibody to varicellazoster virus by immune adherence hemagglutination, Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 151:762, 1976. Gold E, Godek G: Complement fixation studies with a varicella-zoster antigen, J Immunol 95:692, 1965. Passive Immunization Passive immunization for mumps is not effective, and no mumps immune globulin is available. However, prudence dictates that mothers who develop parotitis or other manifestations of mumps in the period immediately antepartum or postpartum should be isolated from other mothers and neonates who lack evidence of mumps immunity, including their own baby. Although one clinical report highlighted that transmission of mumps occurred in a hospital setting, despite isolation of patients with mumps from the time of onset of parotitis,618 isolation of mumps patients is recommended because mumps virus continues to be shed after parotitis onset. There is no scientific evidence that live-attenuated mumps virus vaccine is protective when administered postexposure. It can be considered for exposed hospital personnel and puerperal mothers who lack evidence of mumps immunity, to protect them from future exposures. Some hospitals have the facilities to test for susceptibility to mumps by measurement of antibody titers, whereas others do not. Testing for evidence of immunity on an ongoing basis could eliminate some use of vaccine for the previously described situation. Isolation procedures for mumps include the use of a single room for a patient with the door closed at all times except to enter. Personnel with evidence of mumps immunity caring for the patient should implement droplet precautions (gown and gloves). Bogger-Goren S, Baba K, Hurley P, et al: Antibody response to varicella-zoster virus after natural or vaccine-induced infection, J Infect Dis 146:260, 1982. Luby J, Ramirez-Ronda C, Rinner S, et al: A longitudinal study of varicella zoster virus infections in renal transplant recipients, J Infect Dis 135:659, 1977. Weigle K, Grose C: Molecular dissection of the humoral immune response to individual varicella-zoster viral proteins during chickenpox, quiescence, reinfection, and reactivation, J Infect Dis 149:741, 1984. Gershon A, Steinberg S: Antibody responses to varicella-zoster virus and the role of antibody in host defense, Am J Med Sci 282:12, 1981. Stevens D, Merigan T: Zoster immune globulin prophylaxis of disseminated zoster in compromised hosts, Arch Intern Med 140:52, 1980. Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson J, et al: Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases, Lancet 343:1548, 1994. In Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P, editors: Vaccines, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2013, Saunders, pp 837-869. Watson B, Civen R, Reynolds M, et al: Validity of self-reported varicella disease history in pregnant women attending prenatal clinics, Public Health Rep 122:499, 2007. Baba K, Yabuuchi H, Takahashi M, et al: Increased incidence of herpes zoster in normal children infected with varicella-zoster virus during infancy: community-based follow up study, J Pediatr 108:372, 1986. Gershon A, Raker R, Steinberg S, et al: Antibody to varicella-zoster virus in parturient women and their offspring during the first year of life, Pediatrics 58:692, 1976. Hanngren K, Falksveden L, Grandien M, et al: Zoster immunoglobulin in varicella prophylaxis: a study among high-risk patients, Scand J Infect Dis 15:327, 1983. Gershon A, Steinberg S, Brunell P: Zoster immune globulin: a further assessment, N Engl J Med 290:243, 1974. Bruusgaard E: the mutual relation between zoster and varicella, Br J Dermatol Syphilis 44:1, 1932. Schimpff S, Serpick A, Stoler B, et al: Varicella-zoster infection in patients with cancer, Ann Intern Med 76:241, 1972. Hayakawa Y, Torigoe S, Shiraki K, et al: Biologic and biophysical markers of a live varicella vaccine strain (Oka): identification of clinical isolates from vaccine recipients, J Infect Dis 149:956, 1984. In Krugman S, Gershon A, editors: Infections of the fetus and newborn infant, New York, 1975, Alan R Liss. Systematic differences in contact rates and stochastic effects, Am J Epidemiol 98:469, 1973. Brunell P: Placental transfer of varicella-zoster antibody, Pediatrics 38:1034, 1966. Pinquier D, Gagneur A, Balu L, et al: Prevalence of anti-varicellazoster virus antibodies in French infants under 15 months of age, Clin Vaccine Immunol 16:484, 2009. Leuridan E, Hens N, Hutse V, et al: Kinetics of maternal antibodies against rubella and varicella in infants, Vaccine 29:2222, 2011. Baba K, Yabuuchi H, Takahashi M, et al: Immunologic and epidemiologic aspects of varicella infection acquired during infancy and early childhood, J Pediatr 100:881, 1982. Khandaker G, Marshall H, Peadon E, et al: Congenital and neonatal varicella: impact of the national varicella vaccination programme in Australia, Arch Dis Child 96:453, 2011. Gold E: Serologic and virus-isolation studies of patients with varicella or herpes zoster infection, N Engl J Med 274:181, 1966. Nelson A, St Geme J: On the respiratory spread of varicella-zoster virus, Pediatrics 37:1007, 1966. Trlifajova J, Bryndova D, Ryc M: Isolation of varicella-zoster virus from pharyngeal and nasal swabs in varicella patients, J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 28:201, 1984. Ozaki T, Ichikawa T, Matsui Y, et al: Lymphocyte-associated viremia in varicella, J Med Virol 19:249, 1986. Asano Y, Itakura N, Hiroishi Y, et al: Viremia is present in incubation period in nonimmunocompromised children with varicella, J Pediatr 106:69, 1985. Feldman S, Epp E: Isolation of varicella-zoster virus from blood, J Pediatr 88:265, 1976. Feldman S, Epp E: Detection of viremia during incubation period of varicella, J Pediatr 94:746, 1979. Koropchak C, Graham G, Palmer J, et al: Investigation of varicellazoster virus infection by polymerase chain reaction in the immunocompetent host with acute varicella, J Infect Dis 163:1016, 1991. Mainka C, Fuss B, Geiger H, et al: Characterization of viremia at different stages of varicella-zoster virus infection, J Med Virol 56:91, 1998. Feldman S, Chaudary S, Ossi M, et al: A viremic phase for herpes zoster in children with cancer, J Pediatr 91:597, 1977. Gershon A, Steinberg S, Silber R: Varicella-zoster viremia, J Pediatr 92:1033, 1978. Szanton E, Sarov I: Interaction between polymorphonuclear leukocytes and varicella-zoster infected cells, Intervirology 24:119, 1985. Novakova L, Lehuen A, Novak J: Low numbers and altered phenotype of invariant natural killer T cells in recurrent varicella zoster virus infection, Cell Immunol 269:78, 2011. Etzioni A, Eidenschenk C, Katz R, et al: Fatal varicella associated with selective natural killer cell deficiency, J Pediatr 146:423, 2005.

Purchase cheap voltarol

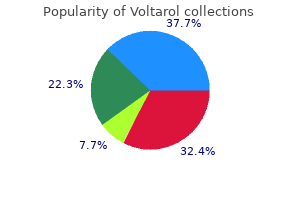

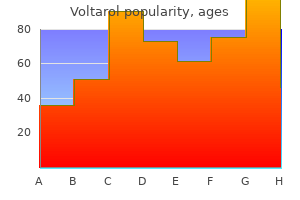

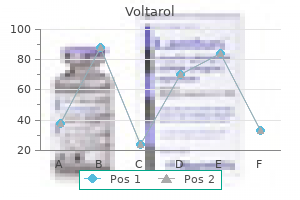

This variation is clearly reflected in the differences seen in the reported cases of gonorrhea the United States in 2011 medications a to z cheap voltarol 100 mg with amex, the most recent year for which this data has been compiled. The United States has set a goal of reducing the national prevalence of gonorrhea to less than 19 cases per 100,000 among adults; however, that goal is unlikely to be met in the near future. Gonorrhea prevalence rates have decreased from 1980, when the prevalence among women was 166/100,000 population. In 2008, the prevalence among women in Canada was approximately 34 per 100,000, which represents a significant increase from 1997, when rates were the lowest at 11 per 100,000. The increase has occurred primarily among women 15 to 19 years of age and 20 to 24 years of age; in these age groups, rates rose from 69 and 60 per 100,000, respectively, in 1997 to 186. Also, as in the United States, rates in Canada vary considerably among the different provinces and territories. Women who have multiple sexual partners or whose partners have multiple sexual contacts markedly increase their risk of exposure to N. Women who do not use condoms or other barrier protection increase their risk of acquisition of N. Factors that are markers for an increased likelihood of gonococcal infection among pregnant women include younger age, unmarried status, homelessness, problems with drug or alcohol abuse, prostitution, low-income professions, and, in the United States, being black. Gonococcal infections are diagnosed more frequently in the summer months in the United States, probably reflecting transient changes in social behavior during vacations. It has been estimated that colonization and infection of the neonate occur in only one third of instances in which the mother is infected. In instances of an ascending infection, the consequences include premature rupture of the membranes with early onset of labor with premature delivery or septic abortion. Worldwide, there has been concern about the development and transmission of antibacterial resistance among isolates of N. Newer testing protocols that involve nonculture techniques have made tracking the development of antibiotic resistance more difficult. Once the resistance rate to an antibiotic is 5% or more, the involved drug is not recommended for general use to treat gonococcal infections. As a result, in the United States penicillin is no longer recommended for primary therapy for gonococcal disease, and tetracycline ointment is not recommended for newborn ocular prophylaxis. When grown in anaerobic conditions, virulent strains express a lipoprotein called Pan 1. Its function is unknown, but it elicits an immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody response in acute infection. Pinpoint colonies, classified as P+ and P++, usually are seen only on primary isolation. This characteristic is related to the expression of a specific surface protein called Opa. Clinical isolates from mucosal surfaces tend to express Opa and form opaque colonies, whereas gonococci isolated from systemic infections tend not to express Opa, and the colonies are more transparent on culture media. Typing of gonococcal isolates for epidemiologic purposes has changed significantly over the past decade with the introduction of newer technologies. Penetration of the gonococcus into cells occurs through either phagocytosis or endocytosis. Several bacteria usually are found within each infected cell, but whether this represents invasion of the cell by multiple organisms or growth and multiplication of organisms within the infected cell is unknown. Gonococci possess a cytotoxic lipopolysaccharide and produce proteases, phospholipases, and elastases that ultimately destroy the infected cells. Some strains of gonococci seem to be relatively less susceptible to phagocytosis and are thought to be more capable of causing disseminated infection. Gonococci are found in the subepithelial connective tissue very quickly after infection. This dissemination may be due to the disruption of the integrity of the epidermal surface with cell death, or the gonococci may migrate into this area by moving between cells. Epithelial cell death triggers a vigorous inflammatory response with the development of small abscesses below the mucosal surface and the production of pus. Initially, this is primarily due to neutrophils but is then replaced over time by macrophages and lymphocytes if the individual is not treated. Human serum contains IgM antibody directed against lipopolysaccharide antigens on the gonococcus, which inhibits invasion. An IgG antibody directed against a surface protein antigen present on some gonococci (classified as serum-resistant gonococci) will block the bactericidal action of the antilipopolysaccharide IgM antibody. Because such infection does not occur frequently, additional protective factors must function to prevent it. This inactivation facilitates mucosal colonization and probably plays a role in the poor mucosal protection seen against subsequent gonococcal reinfection. IgA1 protease is also a proinflammatory factor and can trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines from human monocytic subpopulations and a dose-dependent T-helper type 1 T-cell response. In general, antibody responses are modest after initial infection, however, and no evidence of a boosting effect has been found when antibody levels are studied in response to subsequent infections. Significant antibacterial polypeptide activity has been shown in human amniotic fluid and within the vernix caseosa. At present, chromosomally-mediated resistance is the predominant mechanism for penicillin resistance in North America. The alterations responsible for chromosomal resistance to penicillin include the mtr gene mutation, which increases efflux of antibiotics out of the bacterial cell and which affects several other antibiotics in addition to penicillin; the penA gene mutation, which alters the penicillin binding proteins; and the penB gene mutation, which affects the antibiotic transit through the bacterial membranes. Of recent concern has been the effect of these mutations (which may have been transferred to N. Although not applicable to the pediatric population for systemic use, high levels of resistance rapidly developed for both tetracycline and quinolone classes of antibiotics and eliminated their potential for topical use to prevent infection. Infection of the cornea can lead to ulcerations, perforation, or rarely panophthalmitis, which may result in loss of the eye. Pathology In most affected infants, gonococcal disease manifests as infection of mucosal membranes. The eye is most frequently involved, but funisitis and infant vaginitis, rhinitis, and urethritis also have been observed. When pharyngeal colonization is evaluated, it is found in 35% of ophthalmia neonatorum cases. Gram stain of the exudate usually reveals the gramnegative, intracellular, bean-shaped diplococci typical of N. A definitive diagnosis is important because of the public health and social consequences of the diagnosis of gonorrhea in an infant. If gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum is suspected on the basis of the Gram stain appearance, cultures should be obtained from additional mucosal sites in the infant. Samples of the exudate should be collected by swabbing and should be inoculated directly onto blood agar, MacConkey agar, and chocolate agar or chocolate-inhibitory media. Further testing to confirm the identification of the isolate may be done in a reference laboratory if desired. Their suitability for diagnosis of gonorrheal infections in children without the additional use of culture methods, with the associated legal implications in older children, has not been extensively studied, however. In addition, extensive use of these methods for primary diagnosis impairs the tracking of antimicrobial resistance patterns unless there is a surveillance system such as that in place in the United States. On occasion, the initial presentation is more subacute or the onset may be delayed beyond 5 days of life. The differential diagnosis of cutaneous or systemic gonococcal infection of the neonate includes the bacterial or fungal pathogens that are frequently involved in these types of infections during this time period and are discussed in more detail in Chapters 6, 10, 33, and 34. In other areas, the risk of gonococcal ophthalmia is higher depending on the prevalence of gonococcal infection among the pregnant women in the population.

Helmet Flower (Aconite). Voltarol.

- How does Aconite work?

- Dosing considerations for Aconite.

- Nerve pain, feeling of coldness, facial paralysis, joint pain, gout, inflammation, wounds, heart problems, and other conditions.

- Are there safety concerns?

- What is Aconite?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96604

Best 100 mg voltarol

Zhong H medications that cause dry mouth voltarol 100 mg on-line, Lin Y, Su L, et al: Prevalence of human parechoviruses in central nervous system infections in children: a retrospective study in Shanghai, China, J Med Virol 85:320, 2013. Murphy W: Response of infants to trivalent poliovirus vaccine (Sabin strains), Pediatrics 40:980, 1967. Robino G, Perlman A, Togo Y, et al: Fatal neonatal infection due to Coxsackie B2 virus, J Pediatr 61:911, 1962. Tuuteri L, Lapinleimu K, Meurman L: Fatal myocarditis associated with coxsackie B3 infection in the newborn, Ann Paediatr Fenn 9:56, 1963. Van Creveld S, De Jager H: Myocarditis in newborns, caused by Coxsackie virus: clinical and pathological data, Ann Pediatr 187:100, 1956. Volakova N, Jandasek L: Epidemic of myocarditis in newborn infants caused by Coxsackie B1 virus, Cesk Epidemiol 13:88, 1963. Hasegawa A: Virologic and serologic studies on an outbreak of echovirus type 11 infection in a hospital maternity unit, Jpn J Med Sci Biol 28:179, 1975. Jack I, Grutzner J, Gray N, et al: A survey of prenatal virus disease in Melbourne, Personal communication, July 21, 1967. Steinmann J, Albrecht K: Echovirus 11 epidemic among premature newborns in a neonatal intensive care unit, Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg 259:284, 1985. Daboval T, Ferretti E, Duperval R: High C-reactive protein levels during a benign neonatal outbreak of echovirus type 7, Am J Perinatol 23:299, 2006. Kusuhara K, Saito M, Sasaki Y, et al: An echovirus type 18 outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit, Eur J Pediatr 167:587, 2008. Sato K, Yamashita T, Sakae K, et al: A new-born baby outbreak of echovirus type 33 infection, J Infect 37:123, 1998. Levy O: Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates, Nat Rev Immunol 7:379, 2007. A comparison of viral multiplication and histopathology in infant, adult, and cortisone-treated adult mice infected with the Conn-5 strain of coxsackie virus, J Exp Med 102:753, 1955. Wang J, Atchinson R, Walpusk J, et al: Echovirus hepatic failure in infancy: report of four cases with speculation on the pathogenesis, Pediatr Dev Pathol 4:454, 2001. Kew O, Morris-Glasgow V, Landaverde M, et al: Outbreak of poliomyelitis in Hispaniola associated with circulating type 1 vaccinederived poliovirus, Science 296:356, 2002. Santti J, Hyypia T, Kinnunen L, Salminen M: Evidence of recombination among enteroviruses, J Virol 73:8741, 1999. Simmonds P, Welch J: Frequency and dynamics of recombination within different species of human enteroviruses, J Virol 80:483, 2006. Eisenhut M, Algawi G, Wreghitt T, et al: Fatal coxsackie A9 virus infection during an outbreak in a neonatal unit, J Infect 40:297, 2000. Iwasaki T, Monma N, Satodate R, et al: An immunofluorescent study of generalized coxsackie virus B3 infection in a newborn infant, Acta Pathol Jpn 35:741, 1985. Konen O, Rathaus V, Bauer S, et al: Progressive liver calcifications in neonatal coxsackievirus infection, Pediatr Radiol 30:343, 2000. Chambon M, Delage C, Bailly J, et al: Fatal hepatitis necrosis in a neonate with echovirus 20 infection: use of the polymerase chain reaction to detect enterovirus in the liver tissue, Clin Infect Dis 24:523, 1997. Ventura K, Hawkins H, Smith M, et al: Fatal neonatal echovirus 6 infection: autopsy case report and review of the literature, Mod Pathol 14:85, 2001. Renna S, Bergamino L, Pirlo D, et al: A case of neonatal human parechovirus encephalitis with a favourable outcome, Brain Dev 36:70, 2014. Ito M, Kodama M, Masuko M, et al: Expression of coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor in hearts of rats with experimental autoimmune myocarditis, Circ Res 86:275, 2000. Teisner B, Haahr S: Poikilothermia and susceptibility of suckling mice to coxsackie B1 virus, Nature 247:568, 1974. Arola A, Kalimo H, Ruuskanen O, et al: Experimental myocarditis induced by two different coxsackievirus B3 variants: aspects of pathogenesis and comparison of diagnostic methods, J Med Virol 47:251, 1995. Seko Y, Yoshifumi E, Yagita H, et al: Restricted usage of T-cell receptor Va genes in infiltrating cells in murine hearts with acute myocarditis caused by coxsackie virus B3, J Pathol 178:330, 1996. Philipson L: Association between a recently isolated virus and an epidemic of upper respiratory disease in a day nursery, Arch Gesamte Virusforsch 8:204, 1958. Frisk G, Diderholm H: Increased frequency of coxsackie B virus IgM in women with spontaneous abortion, J Infect 24:141, 1992. Axelsson C, Bondestam K, Frisk G, et al: Coxsackie B virus infections in women with miscarriage, J Med Virol 39:282, 1993. Niklasson B, Samsioe A, Papadogiannakis N, et al: Zoonotic Ljungan virus associated with central nervous system malformations in terminated pregnancy, Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 85:542, 2009. Ouellet A, Sherlock R, Toye B, et al: Antenatal diagnosis of intrauterine infection with coxsackievirus B3 associated with live birth, Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 12:23, 2004. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Congenital Malformations, the Hague, Netherlands, September 7-13, 1969, Amsterdam, 1970, Exerpta Medica International Congress. Harjulehto T, Hovi T, Aro T, et al: Congenital malformations and oral poliovirus vaccination during pregnancy, Lancet 1:771, 1989. Eilard T, Kyllerman M, Wennerblom I, et al: An outbreak of coxsackie virus type B2 among neonates in an obstetrical ward, Acta Paediatr Scand 63:103, 1974. Barre V, Marret S, Mendel I, et al: Enterovirus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in a neonate, Acta Paediatr 87:467, 1998. Grossman M, Azimi P: Fever, hepatitis and coagulopathy in a newborn infant, Pediatr Infect Dis J 11:1069, 1992. Bangalore H, Ahmed J, Bible J, et al: Abdominal distension: an important feature in human parechovirus infection, Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:260, 2011. Eyssette-Guerreau S, Boize P, Thibault M, et al: [Neonatal parechovirus infection, fever, irritability and myositis. Harvala H, Robertson I, Chieochansin T, et al: Specific association of human parechovirus type 3 with sepsis and fever in young infants, as identified by direct typing of cerebrospinal fluid samples, J Infect Dis 199:1753, 2009. Pineiro L, Vicente D, Montes M, et al: Human parechoviruses in infants with systemic infection, J Med Virol 82:1790, 2010. Schuffenecker I, Javouhey E, Gillet Y, et al: Human parechovirus infections, Lyon, France, 2008-10: evidence for severe cases, J Clin Virol 54:337, 2012. Shoji K, Komuro H, Kobayashi Y, et al: An infant with human parechovirus type 3 infection with a distinctive rash on the extremities, Pediatr Dermatol 31:258, 2014. Shoji K, Komuro H, Miyata I, et al: Dermatologic manifestations of human parechovirus type 3 infection in neonates and infants, Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:233, 2013. Chawareewong S, Kiangsiri S, Lokaphadhana K, et al: Neonatal herpangina caused by coxsackie A-5 virus, J Pediatr 93:492, 1978. Murray D, Altschul M, Dyke J: Aseptic meningitis in a neonate with an oral vesicular lesion, Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 3:77, 1985. Nakayama T, Urano T, Osano M, et al: Outbreak of herpangina associated with coxsackievirus B3 infection, Pediatr Infect Dis J 8:495, 1989. Helin I, Widell A, Borulf S, et al: Outbreak of coxsackievirus A-14 meningitis among newborns in a maternity hospital ward, Acta Paediatr Scand 76:234, 1987. Matsumoto K, Yokochi T, Matsuda S, et al: Characterization of an echovirus type 30 variant isolated from patients with aseptic meningitis, Microbiol Immunol 30:333, 1986. Schurmann W, Statz A, Mertens T, et al: Two cases of coxsackie B2 infection in neonates: clinical, virological, and epidemiological aspects, Eur J Pediatr 140:59, 1983. Arnon R, Naor N, Davidson S, et al: Fatal outcome of neonatal echovirus 19 infection, Pediatr Infect Dis J 10:788, 1991. Grangeot-Keros L, Broyer M, Briand E, et al: Enterovirus in sudden unexpected deaths in infants, Pediatr Infect Dis J 15:123, 1996. Aradottir E, Alonso E, Shulman S: Severe neonatal enteroviral hepatitis treated with pleconaril, Pediatr Infect Dis J 20: e457, 2001. Somekh E, Cesar K, Handsher R, et al: An outbreak of echovirus 13 meningitis in central Israel, Epidemiol Infect 130:257, 2003.

Cheap voltarol 100 mg with amex

Because infection involves the placenta40 and spreads hematogenously to the fetus treatment ingrown hair buy generic voltarol 100mg on-line, widespread involvement is characteristic. No matter which organ is involved, the essential microscopic appearance of lesions is that of perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes, with obliterative endarteritis and extensive fibrosis. In pregnancy, a gradual dampening of the intensity of immune responses to favor the maintenance and growth of the fetus may thus result in incomplete clearance of T. Overall, phagocytosis occurs relatively slowly and is facilitated by the presence of immune serum. A 47-kDa treponemal lipoprotein can activate human vascular endothelial cells directly to upregulate cell surface expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and procoagulant activity. Clinically measureable delayed-type hypersensitivity to treponemal antigens appears only late in secondary syphilis and may be related to the onset of latency. Humoral immunity has been a subject of study in syphilis since the serendipitous discovery of antibody to cardiolipin by Wassermann early in the 19th century. As would be expected based on the transplacental transfer of IgG, the IgG levels and antigen specificity of infected infants largely match those of their mothers. In the 19th century in Dublin, Colles124,125 observed that wet nurses who breastfed infants with congenital syphilis often developed chancres of the nipple, whereas the mothers of such infants did not, implying that they were somehow protected from repeated infection; this has become known as the Colles law. Subsequent studies in which prison volunteers in the United States were inoculated with T. Nineteenth-century physicians knew that a degree of maternal immunity is acquired during infection. In 1846, Kassowitz observed that the longer syphilis exists untreated in a woman before pregnancy occurs, the more likely it is that when she does become pregnant, her treponemes will be held in check, and the less likely it is that her fetus will be affected (the Kassowitz law). It also is not clear why some infants who are infected in utero are born without any clinical manifestations, with the subsequent development of overt disease in the first weeks or months of life or even later at puberty. In summary, although active or prior syphilis modifies the response of the patient to subsequent reinfection, protection is unpredictable. Acquired syphilis is a lifelong infection that progresses in three clear characteristic stages93,123: after initial invasion through mucous membranes or skin, the organism undergoes rapid multiplication and disseminates widely. Spread through the perivascular lymphatics and then through the systemic circulation occurs even before the clinical development of the primary lesion. Ten to 90 days later (usually within 3 to 4 weeks), the patient manifests an inflammatory response to the infection at the site of the inoculation. The resulting lesion, the chancre, is characterized by the profuse discharge of spirochetes, accumulation of mononuclear leukocytes and the swelling of capillary endothelia. The regional lymph nodes become enlarged as well, with the cellular infiltrate in the lymph node resembling that of the primary chancre lesions. Resolution of the primary lesion eventually occurs via fibrosis (scarring) at the primary chancre site, and reconstruction of the normal architecture in the lymph node. Secondary lesions develop when tissues of ectodermal origin, such as skin, mucous membranes, and central nervous system, become infected, resulting in vasculitis. There is little or no necrosis, and healing of secondary lesions occurs without scarring. Tertiary syphilis appears to be the result of chronic swelling of the capillary endothelium, resulting in tissue fibrosis or necrosis and may involve any organ system. Gummata are lesions typified by extensive necrosis, a few giant cells, and a paucity of organisms. The other major form of tertiary lesion is a diffuse chronic perivascular inflammation, with plasma cells and lymphocytes but without caseation, that may result in an aortic aneurysm, paralytic dementia, or tabes dorsalis. Of note, most pathologic studies were done on stillborn infants or infants who died early in life, producing significant heterogeneity in the findings secondary to varying length of infection before pathologic examination. Similar to the acquired form, in congenital syphilis, an intense inflammatory response is also focused on the perivascular environment rather than distributed throughout the parenchyma. Other tissues, such as the brain, pituitary gland, lymph nodes, and lungs, may be infected as well. Spirochetes may be identified in placental tissue by using conventional staining, although they may be difficult to visualize,40,48,132 whereas nucleic acid amplification methods readily identify T. The chorionic villi are enlarged and contain dense laminated connective tissue, and the capillaries distributed throughout the villi are compressed by this connective tissue proliferation. The gastrointestinal tract shows a pattern of mononuclear cell infiltration in the mucosa and submucosa, with subsequent thickening resulting from the ensuing fibrosis. Radiographs of long bones show evidence of osteochondritis and periostitis, especially in the long bones and ribs. The excessive fibrosis occurring at the osseous-cartilaginous junction is referred to as "syphilitic granulation tissue" and contains numerous blood vessels surrounded by the inflammatory infiltrate. The basic process of the osseous disturbance seems to involve a failure to convert cartilage in the normal sequence to mature bone. Guarner and associates141 reported that a constant feature throughout the dermal tissues was concentric macrophage infiltrate around vessels, giving an onionskin appearance. The neuropathologic features of congenital syphilis are comparable with those of acquired syphilis, except that the parenchymatous processes (general paresis, tabes dorsalis) are rare. Meningeal involvement is apparent as a discoloration and thickening of the basilar meninges,95 especially around the brainstem and the optic chiasm. Microscopically, endarteritis typically is present, depending on the severity and chronicity of the infection as well as on the blood vessels involved. As the infection resolves, fibrosis can occur, with formation of adhesions that obliterate the subarachnoid space, leading to an obstructive hydrocephalus or to a variety of cranial nerve palsies. Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, at times accompanied by focal necrosis, also have been reported among infants with congenital syphilis. An evolving anterior pituitary gumma was noted at autopsy in a 3-dayold infant with congenital syphilis that did not respond to treatment. Similarly, any generalized skin eruption, regardless of its morphology, should be viewed as secondary (disseminated) syphilis until proven otherwise. Late syphilis, on the other hand, consists of late latent, tertiary, and, depending on nomenclature, quaternary syphilis (or "metalues"). Primary Syphilis in Pregnancy the time between infection with syphilis and the start of the first symptom can range from 10 to 90 days (average, 21 days), at which point a dark red macule or papule develops at the site of inoculation and rapidly progresses to an erosion called a chancre. Chancres often are unrecognized in women because they cause no symptoms and because their location on the labia minora, within the vagina, or on the cervix or perineum makes detection difficult. As a result, only 30% to 40% of infected women are diagnosed in the primary stage. Because the chancre can appear 1 to 3 weeks before a serologic response, direct detection of the pathogen. The mechanism for healing is obscure; it is believed that local immunity is partly responsible because secondary lesions appear during or after the regression of the primary one. However, if adequate treatment is not administered, the infection progresses to the secondary stage. Secondary Syphilis in Pregnancy Two to 10 weeks after the primary lesions, an infected woman may experience secondary disease, characterized by fever, fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, pharyngitis, myalgia, arthralgia, and generalized lymphadenopathy. Because of the protean clinical manifestations, secondary syphilis is often misdiagnosed. However, rashes with a different appearance may occur on any part of the body, and pustular, papular, lichenoid, nodular, ulcerative, plaquelike, annular, and even urticarial and granulomatous forms can occur. The vesiculobullous eruption that is common in congenital syphilis rarely occurs in adults. Contrary to a widely held belief, the exanthema can itch, especially in dark-skinned patients. Rashes associated with secondary syphilis can already appear as the chancre is healing (in approximately 15%, the chancre is still present) or several weeks after the chancre has healed. Various mucosal manifestations can be of diagnostic importance and are present in one third to one half of patients.

Discount voltarol master card

This observation probably reflects the fact that in humans medications similar to vyvanse buy cheap voltarol 100mg online, vascular endothelial cells of the retina are more susceptible than those of other tissues to infection with T. Small vessels in the vicinity of intact bradyzoites are occasionally subject to infiltration with inflammatory cells, and lymphocytes may be observed to adhere to the vascular endothelium and to perivascular tissues but not to neurons. It mediates the control of parasitic proliferation by the activation of microglia, astrocytes, and macrophages, as well as by the local recruitment of T cells. Ocular lesions represent a local manifestation of systemic infection that has spread to the eye by parasite transit through the blood-retina barrier. Reactivation of a latent retinal infection is presumed to follow the rupturing of bradyzoites in the vicinity of preexisting scars and may secondarily involve the choroid, thereby leading to retinochoroiditis. Because toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is deemed to be a local event, it does not usually evoke a systemic immune response. These delayed manifestations have been attributed to the local rupture of cysts within the specific immunoprivileged environment of the eye and brain. In animal models, a positive effect of treatment on the number of tissue cysts in the brain has been reported. However, there is at present no direct evidence that risk is correlated with the number of cysts in the affected tissue compartment. Rupturing of cysts may, however, not represent the sole mechanism underlying recurrences. This finding might imply that leakage, rather than rupturing of cysts, may lead to the formation of smaller satellite cysts. Toxo plasma-containing cysts are encountered within the retina and the optic nerve, irrespective of whether the disease is severe or mild, but less frequently in the latter case. Mild forms of the disease are characterized by low-grade uveitis and by lymphatic perivasculitis. In more severely affected eyes, the retinal destruction may be focal, affect only certain sectors, or be complete. Inflammatory destruction of the outer retina is also sometimes evident and is associated with death of cells or infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells; granulomatous reactions are rare. In very severe cases, the retina may be subject to complete necrosis and calcification. In the adult murine brain, subacute inflammatory tissue changes are manifested in the vicinity of intact bradyzoites in chronic infection. However, this dogma is now being challenged in the face of evidence for active interaction between the immune system and the eye and for an ocular presentation of exogenous and endogenous antigens. According to current knowledge, cell-mediated immune responses and noninflammatory humoral ones are regulated in the eye by cytokine-mediated, active immunosuppressive mechanisms, which include the apoptosis of alloreactive lymphocytes to curb the tissue-destructive effects of inflammatory reactions, both locally and in the brain. Because it develops as an extension of the neural tube, it shares in common with the brain several membranous and cytoplasmic antigens, which include those of the neural and glial filaments. Several antigens that are specific to the nervous system are also abundant in the retina. Antigens that are specific to the eye include those of the retinal pigmented epithelium, retinal ganglion cells, and astrocytes. The outer segments of the photoreceptor cells contain soluble antigens which, when injected into rats, rabbits, guinea-pigs, or monkeys, evoke varying degrees of intraocular inflammation. The inflammatory response can lead to uveitis, to retinal detachment, to degeneration of the photoreceptor cells and occasionally to retinovasculitis. Autoimmunity that is specific to the retina can develop upon its detachment and in conjunction with diabetic retinopathy; in the latter case, particularly after photocoagulation with argon laser light. In patients with systemic immune disorders, such as lupus erythematosus, antibodies against retinal antigens have been detected even in the absence of ocular involvement. Hence the precise pathogenetic role of retinal autoimmunity in ocular diseases, including Toxoplasma-related ocular disease, is not known with certainty. It may represent no more than an epiphenomenon that develops after physically, immunologically, or microbially induced retinal damage. On the other hand, although retinal autoimmunity alone may fail to evoke ocular inflammation, it could perpetuate and sustain the level of a preexisting inflammatory state, thereby leading to further destruction of ocular tissues. Specific IgE was detected in two thirds of the patients with autoimmune uveitis but not in the control group or in individuals with bacterial uveitis. In patients with ocular toxoplasmosis, a strong antiretinal signal in the photoreceptor cell layers was reported to occur in greater than 90% of the individuals, whereas in healthy control subjects and in subjects with retinovasculitis, a lower level of reactivity was detected at the same site in only 40% of cases. Antibodies against the retinal S-antigen were detected in 75% of the patients suffering from either ocular toxoplasmosis or retinovasculitis but also in greater than 60% of the healthy control subjects. The prevalence of antiphotoreceptor antibodies indicates that they occur naturally, although the higher degree of reactivity in those with ocular toxoplasmosis suggest that such antibodies could play a contributory role in disease pathogenesis. The position of necrotic foci and lesions in general suggests that the organisms reach the brain and all other organs through the bloodstream. Noteworthy is the remarkable variability in distribution of lesions and parasites among the different reported cases. After the appearance of early reports of cases of congenital toxoplasmosis, the prevailing impression was that the infection manifested itself in infants mainly as an encephalomyelitis and that visceral lesions were uncommon and insignificant. This view reflected the observation of a marked degree of damage * In the absence of relevant new data, this portion of the chapter has remained unchanged from the 7th edition Chapter 31, by Jack S. Active regeneration of extraneural tissues may be observed even in the most acute stages of infection in the infant. The diffuse character of the lung changes contrasts with the more focal lesions found in other organs and tissues. Zuelzer197 pointed out that this difference may be due to the position of the lungs in the route of circulation. Before dissemination to other tissues of the body all blood with parasites entering the venous circulation must first pass through the alveolar capillaries. In five cases studied by Benirschke and Driscoll,203 the most consistent findings in the placentas were chronic inflammatory reactions in the decidua capsularis and focal reactions in the villi. Single or multiple neighboring villi with low-grade chronic inflammation, activation of Hofbauer cells, necrobiosis of component cells, and proliferative fibrosis may be seen. Although villous lesions frequently are observed in placental toxoplasmosis, histologic examination of these foci does not reveal parasites; they occur in free villi and in villi attached to the decidua. Lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells, but rarely plasma cells, make up the intravillous and perivillous infiltrates. Mellgren and coworkers,201 Benirschke and Driscoll,203 and Nowakowska and coworkers209 observed one specimen from which the parasite was isolated, in which contiguous decidua capsularis, chorion, and amnion contained organisms. In a retrospective histologic examination of 13 placentas of newborns with serologic test results suggestive of congenital T. Of interest is that in 10 of their cases, on gross examination, the placenta was found to be abnormal, suggesting the diagnosis of prolonged fetal distress, hematogenous infection, or both. The fetal villi showed hydrops, an abundance of Hofbauer cells, and vascular proliferation. Elliott202 described lesions in a placenta after a third-month spontaneous abortion of a macerated fetus. The placenta showed nodular accumulations of histiocytes beneath the syncytial layer. In villi that had pronounced histiocytic infiltrates, the syncytial layer was raised away from the villous stroma, and the infiltrate had spilled into the intervillous space. Disruption of the syncytium was associated with coagulation necrosis of the villous stroma and fibrinous exudate. The location of the organisms varied, but they seemed to be concentrated at the interface between the stroma and the trophoblast. This aggregation of histiocytes and organisms at the stroma-trophoblast interface suggested to Elliott that this is a favored site of growth for the parasite. D, Section of brain showing abscess (left), normal brain (right), and area of gliosis (middle). The pia-arachnoid overlying destructive cortical or spinal cord lesions shows congestion of the vessels and infiltration of large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and eosinophils. This type of change is particularly noticeable around small arterioles, venules, and capillaries.