Generic 200mg red viagra otc

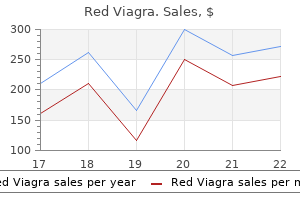

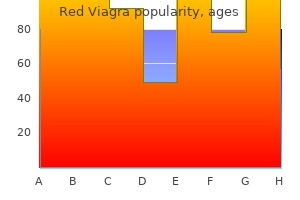

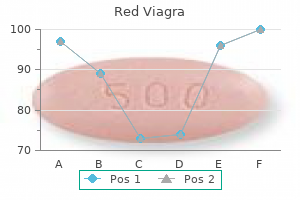

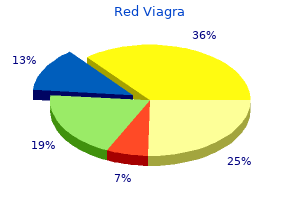

For example erectile dysfunction after drug use buy red viagra 200 mg otc, tumors in the ascending colon are more common among women and older patients whereas rectosigmoidal tumors are more common among men and younger patients. Mobile Ascending Colon When the inerior part o the ascending colon has a mesentery, the cecum and proximal part o the colon are abnormally mobile. This condition, present in approximately 11% o individuals, may cause cecal bascule (olding o the mobile cecum) or, less commonly, cecal volvulus (L. In this anchoring procedure, a tenia coli o the cecum and proximal ascending colon is sutured to the abdominal wall. Colitis, Colectomy, Ileostomy, and Colostomy Chronic infammation o the colon (ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease) is characterized by severe infammation and ulceration o the colon and rectum. In some cases, a colectomy is perormed, during which the terminal ileum and colon, as well as the rectum and anal canal, are removed. An ileostomy is then constructed to establish a stoma, an articial opening o the ileum through the skin o the anterolateral abdominal wall. The terminating ileum is delivered through and sutured to the periphery o an opening in the anterolateral abdominal wall, allowing the egress o its contents. Similarly, ollowing a partial colectomy, a colostomy or sigmoidostomy is perormed to create an articial cutaneous opening or the terminal part o the colon. Sometimes surgeons create a temporary ostomy to allow the bowel to heal ater resection and anasto- Diverticulosis Diverticulosis is a disorder in which multiple alse diverticula (external evaginations or outpocketings o the mucosa o the colon) develop along the intestine. Colonic diverticula are not true diverticula because they are ormed rom protrusions o mucous membrane only, evaginated through weak points (separations) developed between muscle bers rather than involving the whole wall o the colon. They occur most commonly on the mesenteric side o the two nonmesenteric teniae coli, where nutrient arteries perorate the muscle coat to reach the submucosa. Diverticula are subject to inection and rupture, leading to diverticulitis, which can distort and erode the nutrient arteries, leading to hemorrhage. Descending colon Volvulus o Sigmoid Colon Rotation and twisting o the mobile loop o the sigmoid colon and mesocolon-volvulus o the sigmoid colon. Obstipation (inability o the stool or fatus to pass) and ischemia (absence o blood fow) o the looped part o the sigmoid colon result. Volvulus is an acute emergency, and unless it resolves spontaneously, necrosis (tissue death) o the involved segment may occur i untreated. The esophagus penetrates the diaphragm at the T10 vertebral level, passing through its right crus, which decussates around it to orm the physiological inerior esophageal sphincter. The trumpet-shaped abdominal part, composed entirely o smooth muscle innervated by the esophageal nerve plexus, enters the cardial part o the stomach. The abdominal part o the esophagus receives blood rom esophageal branches o the let gastric artery (rom the celiac trunk). Submucosal veins drain to both the systemic and portal venous systems and thus constitute portocaval anastomoses that may become varicose in the presence o portal hypertension. Internally, in living people, the esophagus is demarcated rom the stomach by an abrupt mucosal transition, the Z-line. Stomach: the stomach is the dilated portion o the alimentary tract between the esophagus and the duodenum, continued on next page 486 Chapter 5 Abdomen the Bottom Line (continued) specialized to accumulate ingested ood and prepare it chemically and mechanically or digestion. The stomach lies asymmetrically in the abdominal cavity, to the let o the midline and usually in the upper let quadrant. However, the position o the stomach can vary markedly in persons o dierent body types. The abdominal portion o the esophagus enters its cardial portion, and its pyloric part leads to the exit to the duodenum. In lie, the internal surace o the stomach is covered with a protective layer o mucus, overlying gastric olds that disappear with distension. The stomach is intraperitoneal, with the lesser omentum (enclosing the anastomoses between right and let gastric vessels) attached to its lesser curvature and the greater omentum (enclosing the anastomoses between right and let gastro-omental vessels) attached to its greater curvature. The trilaminar smooth muscle o the stomach and gastric glands receives parasympathetic innervation rom the vagus; sympathetic innervation to the stomach is vasoconstrictive and antiperistaltic. The duodenum ollows a mostly secondarily retroperitoneal, C-shaped course around the head o the pancreas. The descending part o the duodenum receives both the bile and the pancreatic ducts. At or just distal to this level, a transition occurs in the blood supply o the abdominal part o the digestive tract. Proximal to this point, it is supplied by branches o the celiac trunk; distal to this point, it is supplied by branches o the superior mesenteric artery. The jejunum and ileum make up the convolutions o the small intestine occupying most o the inracolic division o the greater sac o the peritoneal cavity. The orad (proximal relative to the mouth) two fths is jejunum and the aborad (distal) three fths is ileum, although there is no clear line o transition. The diameter o the small intestine becomes increasingly smaller as the semiuid chyme progresses through it. Its blood vessels also become smaller, but the number o tiers o arcades increases while the length o the vasa recta decreases. The at in which the vessels are embedded within the mesentery increases, making these eatures more difcult to see. The ileum is characterized by an abundance o lymphoid tissue, aggregated into lymphoid nodules (Peyer patches). The intraperitoneal portion o the small intestine (jejunum and ileum) is suspended by the mesentery, the root o which extends rom the duodenojejunal junction to the let o the midline at the L2 level to the ileocecal junction in the right iliac ossa. Large intestine: the large intestine consists o the cecum; appendix; ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon; rectum; and anal canal. The large intestine is characterized by teniae coli, haustra, omental appendices, and a large caliber. The large intestine begins at the ileocecal valve; but its frst part, the cecum, is a pocket that hangs inerior to the valve. The pouch-like cecum, the widest part o the large intestine, is completely intraperitoneal and has no mesentery, so that it is mobile within the right iliac ossa. The ileocecal valve is a combination valve and weak sphincter, actively opening periodically to allow entry o ileal contents and orming a largely passive one-way valve between the ileum and the cecum, preventing reux. The appendix is an intestinal diverticulum, rich in lymphoid tissue, that enters the medial aspect o the cecum, usually deep to the junction o the lateral third and medial two thirds o the spino-umbilical line. Most commonly, the appendix is retrocecal in position, but 32% o the time, it descends into the lesser pelvis. The ascending colon is a superior, secondarily retroperitoneal continuation o the cecum, extending between the level o the ileocecal valve and the right colic exure. The transverse colon, suspended by the transverse mesocolon between the right and let exures, is the longest and most mobile part o the large intestine. The descending colon occupies a secondarily retroperitoneal position between the let colic exure and let iliac ossa, where it is continuous with the sigmoid colon. The S-shaped sigmoid colon, suspended by the sigmoid mesocolon, is highly variable in length and disposition, ending at the rectosigmoid junction. The part o large intestine orad (proximal) to the let colic exure (cecum, appendix, and ascending and transverse colons) is served by branches o the superior mesenteric vessels. Aborad (distal) to the exure, most o the remainder o the large intestine (descending and sigmoid colons and superior rectum) is served by the inerior mesenteric vessels. The let colic exure also marks the divide between cranial (vagal) and sacral (pelvic splanchnic) parasympathetic innervation o the alimentary tract. Sympathetic fbers are conveyed to the large intestine via abdominopelvic (lesser and lumbar) splanchnic nerves via the prevertebral (superior and inerior mesenteric) ganglia and peri-arterial plexuses. The middle o the sigmoid colon marks a divide in the sensory innervation o the abdominal alimentary tract: orad, visceral aerents or pain travel retrogradely with sympathetic fbers to spinal sensory ganglia, whereas those conveying reex inormation travel with parasympathetic fbers to vagal sensory ganglia; aborad, both types o visceral aerent fbers travel with parasympathetic fbers to spinal sensory ganglia. In spite o its size and the many useul and important unctions it provides, it is not a vital organ (not necessary to sustain lie). To accommodate these unctions, the spleen is a sot, vascular (sinusoidal) mass with a relatively delicate broelastic capsule. The thin capsule is covered with a layer o visceral peritoneum that entirely surrounds the spleen except at the splenic hilum, where the splenic branches o the splenic artery and vein enter and leave. Consequently, it is capable o marked expansion and some relatively rapid contraction. The spleen is a mobile organ although it normally does not descend inerior to the costal (rib) region; it rests on the let colic fexure.

Order red viagra online now

Intervention for Aortic Valve Stenosis beyond the Neonatal Period Balloon dilation of the aortic valve is a low-risk procedure which serves both to reduce the transvalvular gradient and to promote growth of the aortic annulus erectile dysfunction doctors long island discount red viagra 200 mg with amex. The latter is important because aortic stenosis in children is often associated with hypoplasia of the aortic valve. Balloon dilation of a stenotic valve early in life, particularly if it results in a mild degree of aortic regurgitation, provides an important stimulus for growth of the valve. These gradients are considerably lower than those previously used as the threshold for surgical intervention in children. Early aggressive intervention by balloon dilation allows the child to grow and exercise and promotes annular growth. At present, there are essentially no indications for primary surgical intervention for a stenotic aortic valve with adequate annular dimensions. Ross later introduced the pulmonary autograft procedure41 which has subsequently been combined with the Konno procedure for patients with annular hypoplasia and particularly those with associated tunnel subaortic stenosis. However, aortic valve repair for predominant regurgitation is described in Chapter 21, Valve Repair and Replacement. Repair often includes techniques to eliminate a rigid raphe or commissural fusion which both contribute to stenosis when regurgitation coexists with stenosis. Aortic Valve Replacement with Aortic Annular Enlargement Aortic valve replacement for pure aortic valve stenosis with a normal aortic annular diameter is almost never indicated in the pediatric age group. If an aggressive policy of balloon valve dilation is followed it will also be rare that the aortic valve needs replacement because of annular hypoplasia. Posterior Enlargement of the Aortic Annulus: Manougian and Nicks Procedures these procedures are used alone when a modest degree of enlargement of the aortic annulus is required. They can be applied together with an anterior Konno-type annular procedure when more aggressive enlargement is needed (see below). Posterior 426 Comprehensive Surgical Management of Congenital Heart Disease, Second Edition root replacement using an aortic homograft in the small aortic root. They are generally not performed in conjunction with the Ross procedure (see below). Nicks Procedure A standard reverse hockey-stick incision is made extending the incision inferiorly toward the area between the left/noncommissure and the base of the noncoronary commissure. The incision is not carried into the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve but is simply carried into the area of fibrous continuity between the aortic and mitral valves. A collagen impregnated woven Dacron patch is used to supplement the annulus though in the smaller child autologous pericardium may be preferred. The aortic valve leaflets are excised and horizontal mattress pledgetted sutures are placed except in the region of the patch where they are passed through the patch. Inverting sutures placed below the prosthesis allow a larger prosthesis to be placed relative to everting sutures placed above the prosthesis. Another option is to place all sutures from outside the aorta with care to avoid compromise of the coronaries. The heart is de-aired in the usual fashion and when rewarming is completed discontinuation of bypass should be routine. Manougian Procedure the incision is as for the Nicks procedure but is extended across the intervalvular fibrosa into the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve at the commissure between the left and noncoronary leaflets. However, it can be easily picked up in the supplementing patch suture line and, in fact, serves a useful function in pledgetting the suture line. The Manougian procedure can be performed in conjunction with homograft replacement of the aortic root. In these circumstances, the annulus is supplemented by the mitral valve component of the homograft. Consideration should be given to using Prolene sutures pledgetted with pericardium to buttress this suture line. If a prosthetic valve replacement is performed rather than a homograft root replacement it is probably best to use autologous pericardium treated with glutaraldehyde to close the defect in the mitral valve and to enlarge the aortic annulus and aortic root. Extended Aortic Root Replacement with Aortic Homograft Although there are very few indications for this procedure it is occasionally useful in the setting of bacterial endocarditis. After extending the incision in the noncoronary sinus into the middle of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve, the now enlarged aortic annulus is sized and an appropriate aortic homograft is selected. The base of the homograft is now sutured to the supplemented aortic annulus using continuous 4/0 Prolene. A number of interrupted pledgetted horizontal mattress sutures are used as a second supporting row particularly across the muscular septal component of the homograft. Additional sutures should be placed as necessary as hemostasis in this area will be difficult when the procedure is completed. The distal ascending aortic anastomosis is fashioned after a marking suture has been placed externally to indicate the top of the anterior commissure of the homograft aortic valve. The root is distended with cardioplegia and the appropriate site for reimplantation of the right coronary artery is selected. Anteriorly the annulus can be enlarged with a Konno incision which extends between the right and left coronary cusps of the aortic valve. If the subaortic area is to be enlarged the Konno incision is extended into the ventricular septum. Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction 427 this button to avoid injuring the homograft aortic valve, the location of which is indicated by the marking suture. The Konno procedure ("classic Konno") was originally described to allow insertion of an adequate size prosthetic aortic valve. The procedure carries significant disadvantages and risks in children including the need for permanent anticoagulation, a risk of paravalvar leak with associated hemolysis as well as a risk of projection of the rigid mechanical valve into the right ventricular outflow tract. For these reasons we avoided the classic Konno procedure for many years preferring a homograft root replacement with Konno. However, longer-term follow-up of patients after homograft root replacement and after the Ross procedure when this is performed as a root replacement has caused us to reconsider use of the classic Konno procedure. Disadvantages of the Ross/Konno procedure include a need for lifelong homograft conduit changes in the right ventricular outflow tract, a risk of neoaortic root dilation with attendant neoaortic valve regurgitation as well as a risk of aneurysm formation of the subaortic patch. If the aortic annulus is to be enlarged a Konno-type incision is made between the right and left coronary leaflets extending into the ventricular septum. Cardiopulmonary Bypass Setup Two straight or right angle caval cannulas with caval tapes are employed with arterial cannulation of the ascending aorta. Multiple infusions of cardioplegia are given throughout this relatively lengthy procedure. The aortic root and aortic valve are completely excised in the manner of an extended aortic root replacement. The coronary arteries are mobilized with generous "U-shaped" buttons of aortic wall attached (the shape facilitates correct orientation during reimplantation). It is the support of the pulmonary valve by a ring of muscle, the subpulmonary conus, that makes the autograft procedure possible. The subpulmonary conus that is divided to harvest the autograft is subsequently used as the sewing ring to implant the pulmonary root. A right angle instrument is passed down through the valve and acts as a guide for the initial incision in the anterior wall of the infundibulum of the right ventricle. Failure to do this can result in placing the incision too close to the pulmonary valve. Consideration should be given to harvesting a little more infundibulum than for a standard Ross procedure if a Konno procedure is to be added as well. Following the initial incision in the anterior wall of the infundibulum the autograft is harvested with particular care being taken at the leftward extent of the incision which is always very close to the first septal perforator branch of the left anterior descending coronary artery. We generally excise this portion of the autograft last after careful posterior mobilization with visualization of the left main coronary and its bifurcation. If the septal perforator is injured it is very important that it be repaired or at least oversewn. Failure to repair an injured perforator is likely to result in a steal of blood from the entire left coronary system. This has potential to cause considerably more ischemic injury than would be expected from injury to the perforator alone. The autograft is stored in a bowl which is clearly marked and separated from the pulmonary homograft which should be undergoing thawing and rinsing at this stage.

Order red viagra 200mg mastercard

Its head has two acets or articulation with the bodies o the T1 and T2 vertebrae; its main atypical eature is a rough area on its upper surace erectile dysfunction age onset cheap red viagra line, the tuberosity or serratus anterior, rom which part o that muscle originates. Costal cartilages prolong the ribs anteriorly and contribute to the elasticity o the thoracic wall, providing a fexible attachment or their anterior ends (tips). The rst 7 costal cartilages attach directly and independently to the sternum; the 8th, 9th, and 10th articulate with the costal cartilages just superior to them, orming a continuous, articulated, cartilaginous costal margin. The 11th and 12th costal cartilages orm caps on the anterior ends o the corresponding ribs and do not reach or attach to any other bone or cartilage. The spaces are named according to the rib orming the superior border o the space- or example, the 4th intercostal space lies between ribs 4 and 5. Intercostal spaces are occupied by intercostal muscles and membranes, and two sets (main and collateral) o intercostal blood vessels and nerves, identied by the same number assigned to the space. The space below the 12th rib does not lie between ribs and thus is reerred to as the subcostal space, and the anterior ramus (branch) o spinal nerve T12 is the subcostal nerve. The spaces widen urther with inspiration and on contralateral extension and/or lateral fexion o the thoracic vertebral column. Each rib has a spongy interior containing bone marrow (hematopoietic tissue), which orms blood cells. False (vertebrochondral) ribs (8th, 9th, and usually 10th ribs): Their cartilages are connected to the cartilage o the rib above them; thus, their connection with the sternum is indirect. Floating (vertebral, ree) ribs (11th, 12th, and sometimes 10th ribs): the rudimentary cartilages o these ribs do not connect even indirectly with the sternum; instead, they end in the posterior abdominal musculature. Tubercle: located at the junction o the neck and body; a smooth articular part articulates with the corresponding transverse process o the vertebra, and a rough nonarticular part provides attachment or the costotransverse ligament. Body (shat): thin, fat, and curved, most markedly at the costal angle where the rib turns anterolaterally. The angle also demarcates the lateral limit o attachment o the deep back muscles to the ribs. The concave internal surace o the body has a costal groove paralleling the inerior border o the rib, which provides some protection or the intercostal nerve and vessels. T1 has a vertebral oramen and body similar in size and shape to a cervical vertebra. The planes o the articular acets o thoracic vertebrae defne an arc (red arrows) that centers on an axis traversing the vertebral bodies vertically. Superior and inerior costal acets (demiacets) on the vertebral body and costal acets on the transverse processes. The rib moves (elevates and depresses) around an axis that traverses the head and neck o the rib (arrows). Characteristic eatures o thoracic vertebrae include the ollowing: Bilateral costal acets (demiacets) on the vertebral bodies, usually occurring in inerior and superior pairs, or articulation with the heads o ribs. Costal acets on the transverse processes or articulation with the tubercles o ribs, except or the inerior two or three thoracic vertebrae. Atypical thoracic vertebrae bear whole costal acets in place o demiacets: the superior costal acets o vertebra T1 are not demiacets because there are no demiacets on the C7 vertebra above, and rib 1 articulates only with vertebra T1. Clavicular notch Jugular notch Costal cartilage of 1st rib Synchondrosis of first rib Manubrium (M) Sternal angle (manubriosternal joint) (A) 3rd Costal notches 2nd Costal notches 3rd Clavicular notch T10 has only one bilateral pair o (whole) costal acets, located partly on its body and partly on its pedicle. T11 and T12 also have only a single pair o (whole) costal acets, located on their pedicles. The spinous processes projecting rom the vertebral arches o typical thoracic vertebrae. They cover the intervals between the laminae o adjacent vertebrae, thereby preventing sharp objects such as a knie rom entering the vertebral canal and injuring the spinal cord. The convex superior articular acets o the superior articular processes ace mainly posteriorly and slightly laterally, whereas the concave inerior articular acets o the inerior articular processes ace mainly anteriorly and slightly medially. The bilateral joint planes between the respective articular acets o adjacent thoracic vertebrae deine an arc, centering on an axis o rotation within the vertebral body. Thus, small rotatory movements are permitted between adjacent vertebrae, limited by the attached rib cage. The thin, broad membranous bands o the radiate sternocostal ligaments pass rom the costal cartilages to the anterior and posterior suraces o the sternum-is shown on the upper right side. Observe the thickness o the superior third o the manubrium between the clavicular notches. Thoracic Wall 297 or mediastinal viscera in general and much o the heart in particular. In adolescents and young adults, the three parts are connected together by cartilaginous joints (synchondroses) that ossiy during middle to late adulthood. The easily palpated concave center o the superior border o the manubrium is the jugular notch (suprasternal notch). Inerolateral to the clavicular notch, the costal cartilage o the 1st rib is tightly attached to the lateral border o the manubrium-the synchondrosis o the irst rib. The manubrium and body o the sternum lie in slightly dierent planes superior and inerior to their junction, the manubriosternal joint. Its width varies because o the scalloping o its lateral borders by the costal notches. The sternebrae articulate with each other at primary cartilaginous joints (sternal synchondroses). These joints begin to use rom the inerior end between puberty (sexual maturity) and age 25. The nearly fat anterior surace o the body o the sternum is marked in adults by three variable transverse ridges. The xiphoid process, the smallest and most variable part o the sternum, is thin and elongated. Although oten pointed, the process may be blunt, bid, curved, or defected to one side or anteriorly. It is cartilaginous in young people but more or less ossied in adults older than age 40. The xiphoid process is an important landmark in the median plane because its junction with the sternal body at the xiphisternal joint indicates the inerior limit o the central part o the thoracic cavity; this joint is also the site o the inrasternal angle (subcostal angle) ormed by the right and let costal margins. Thoracic Apertures While the thoracic cage provides a complete wall peripherally, it is open superiorly and ineriorly. The larger inerior opening provides the ring-like origin o the diaphragm, which completely occludes the opening. Excursions o the diaphragm primarily control the volume/internal pressure o the thoracic cavity, providing the basis or tidal respiration (air exchange). Structures that pass between the thoracic cavity and neck through the oblique, kidney-shaped superior thoracic aperture include the trachea, esophagus, nerves, and vessels that supply and drain the head, neck, and upper limbs. The superior thoracic aperture is the "doorway" between the thoracic cavity and the neck and upper limb. The inerior thoracic aperture provides attachment or the diaphragm, which protrudes upward so that upper abdominal viscera. Because o the obliquity o the 1st pair o ribs, the aperture slopes antero-ineriorly. These joints are discussed with the Back in Chapter 1; the sternoclavicular joints are discussed with the Upper Limb in Chapter 3. The inerior thoracic aperture is much more spacious than the superior thoracic aperture and is irregular in outline. It is also oblique because the posterior thoracic wall is much longer than the anterior wall.

Buy generic red viagra

While not true terminal arteries erectile dysfunction treatment in kenya generic red viagra 200 mg on line, unctional terminal arteries (arteries with ineectual anastomoses) supply segments o the brain, liver, kidneys, spleen, and intestines; they may also exist in the heart. Both eects make it easier or the musculovenous pump to overcome the orce o gravity to return blood to the heart. Examples o medium veins include the named supercial veins (cephalic and basilic veins o the upper limbs and great and small saphenous veins o the lower limbs) and the accompanying veins that are named according to the artery they accompany. Large veins are characterized by wide bundles o longitudinal smooth muscle and a well-developed tunica adventitia. Although their walls are thinner, their diameters are usually larger than those o the corresponding artery. The thin walls allow veins to have a large capacity or expansion and do so when blood return to the heart is impeded by compression or internal pressures. Since the arteries and veins make up a circuit, it might be expected that hal the blood volume would be in the arteries and hal in the veins. Although oten depicted as single vessels in illustrations or simplicity, veins tend to be double or multiple. This arrangement serves as a countercurrent heat exchanger, the warm arterial blood warming the cooler venous blood as it returns to the heart rom a cold limb. The accompanying veins occupy a relatively unyielding ascial vascular sheath with the artery they accompany. As a result, they are stretched and fattened as the artery expands during contraction o the heart, which aids in driving venous blood toward the heart-an arteriovenous pump. Systemic veins are more variable than arteries, and venous anastomoses-natural communications, direct or indirect, between two veins-occur more oten between them. The outward expansion o the bellies o contracting skeletal Veins generally return low-oxygen blood rom the capillary beds to the heart, which gives the veins a dark blue appearance. The large pulmonary veins are atypical in that they carry oxygen-rich blood rom the lungs to the heart. Because o the lower blood pressure in the venous system, the walls (specically, the tunica media) o veins are thinner than those o their companion arteries. Small veins are the tributaries o larger veins that unite to orm venous plexuses (networks o veins), such as the dorsal venous arch o the oot. In the limbs, and in some other locations where the fow o blood is opposed by the pull o gravity, the medium veins have valves. Venous valves are cusps (passive faps) o endothelium with cup-like valvular sinuses that ll rom above. When they are ull, the valve cusps occlude the lumen o the vein, thereby preventing refux o blood distally, making fow unidirectional (toward the heart but not in the reverse direction; see. The valvular mechanism also breaks columns o blood in the veins into shorter segments, Accompanying veins (L. Although most veins o the trunk occur as large single vessels, veins in the limbs occur as two or more smaller vessels that accompany an artery in a common vascular sheath. Cardiovascular System 41 muscles in the limbs, limited by the deep ascia, compresses the veins, "milking" the blood superiorly toward the heart; another (musculovenous) type o venous pump. The valves o the veins break up the columns o blood, thus relieving the more dependent parts o excessive pressure, allowing venous blood to fow only toward the heart. Capillaries are generally arranged in capillary beds, networks that connect the arterioles and venules. The blood enters the capillary beds through arterioles that control the fow and is drained rom them by venules. As the hydrostatic pressure in the arterioles orces blood into and through the capillary bed, it also orces fuid containing oxygen, nutrients, and other cellular materials out o the blood at the arterial end o the capillary bed (upstream) into the extracellular spaces, allowing exchange with cells o the surrounding tissue. Muscular contractions in the limbs unction with the venous valves to move blood toward the heart. The outward expansion o the bellies o contracting muscles is limited by deep ascia and becomes a compressive orce, propelling the blood against gravity. In some situations, blood passes through two capillary beds beore returning to the heart; a venous system linking two capillary beds constitutes a portal venous system. The venous system by which nutrient-rich blood passes rom the capillary beds o the alimentary tract to the capillary beds or sinusoids o the liver-the hepatic portal system-is the major example. A common orm, atherosclerosis, is associated with the buildup o at (mainly cholesterol) in the arterial walls. A calcium deposit orms an atheromatous plaque (atheroma)-well-demarcated, hardened yellow areas or swellings on the intimal suraces o arteries. The consequences o atherosclerosis include ischemia (reduction 42 Chapter 1 Overview and Basic Concepts o blood supply to an organ or region) and inarction (local death, or necrosis, o an area o tissue or an organ resulting rom reduced blood supply). Varicose veins have a caliber greater than normal, and their valve cusps do not meet or have been destroyed by infammation. Varicose veins have incompetent valves; thus, the column o blood ascending toward the heart is unbroken, placing increased pressure on the weakened walls, urther exacerbating the varicosity problem. Incompetent ascia is incapable o containing the expansion o contracting muscles; thus, the (musculoascial) musculovenous pump is ineective. A weakened vein dilates under the pressure o supporting a column o blood against gravity. The Starling hypothesis (see "Blood Capillaries" in this chapter) explains how most o the fuid and electrolytes entering the extracellular spaces rom the blood capillaries is also reabsorbed by them. Furthermore, some plasma protein leaks into the extracellular spaces, and material originating rom the tissue cells that cannot pass through the walls o blood capillaries, such as cytoplasm rom disintegrating cells, continually enters the space in which the cells live. I this material were to accumulate in the extracellular spaces, a reverse osmosis would occur, bringing even more fuid and resulting in edema (an excess o interstitial fuid, maniest as swelling). However, the amount o interstitial fuid remains airly constant under normal conditions, and proteins and cellular debris normally do not accumulate in the extracellular spaces because o the lymphoid system. The lymphoid system thus constitutes a sort o "overfow" system that provides or the drainage o surplus tissue fuid and leaked plasma proteins to the bloodstream, as well as or the removal o debris rom cellular decomposition and inection. Lymphatic vessels (lymphatics), thin-walled vessels with abundant lymphatic valves that comprise a nearly body-wide network to drain lymph rom the lymphatic capillaries. In living individuals, the vessels bulge where each o the closely spaced valves occur, giving lymphatics a beaded appearance. Lymphatic trunks are large collecting vessels that receive lymph rom multiple lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic capillaries and vessels occur almost everywhere blood capillaries are ound, except or example, teeth, bone, bone marrow, and the entire central nervous system. Except or the right superior quadrant o the body (pink), lymph ultimately drains into the let venous angle via the thoracic duct. The right superior quadrant drains to the right venous angle, usually via a right lymphatic duct. Lymph typically passes through several sets o lymph nodes, in a generally predictable order, beore it enters the venous system. Small black arrows indicate the ow (leaking) o interstitial uid out o blood capillaries and (absorption) into the lymphatic capillaries. Lymph nodes, small masses o lymphatic tissue located along the course o lymphatic vessels through which lymph is ltered on its way to the venous system. Lymphocytes, circulating cells o the immune system that react against oreign materials. Lymphoid organs, parts o the body that produce lymphocytes, such as the thymus, red bone marrow, spleen, tonsils, and the solitary and aggregated lymphoid nodules in the walls o the alimentary tract and appendix. Superfcial lymphatic vessels, more numerous than veins in the subcutaneous tissue and anastomosing reely, converge toward and ollow the venous drainage. These vessels eventually drain into deep lymphatic vessels that accompany the arteries and also receive the drainage o internal organs. It is likely that the deep lymphatic vessels are also compressed by the arteries they accompany, milking the lymph along these valved vessels in the same manner described earlier or accompanying veins. Both supercial and deep lymphatic vessels traverse lymph nodes (usually several sets) as they course proximally, becoming larger as they merge with vessels draining adjacent regions. Large lymphatic vessels enter large collecting vessels, called lymphatic trunks, which unite to orm either the right lymphatic duct or the thoracic duct.

Purchase red viagra 200 mg on line

The palmar and dorsal cutaneous branches arise rom the ulnar nerve in the orearm impotence exercise buy 200mg red viagra mastercard, but their sensory bers are distributed to the skin o the hand. The median nerve has no branches in the arm other than small twigs to the brachial artery. In addition, the ollowing unnamed branches o the median nerve arise in the orearm: Articular branches. The nerve to the pronator teres usually arises at the elbow and enters the lateral border o the muscle. This branch runs distally on the interosseous membrane with the anterior interosseous branch o the ulnar artery. However, its sensory and motor bers are distributed in the orearm by two separate branches, the supercial (sensory or cutaneous) and deep radial/posterior interosseous nerve (motor). It divides into these terminal branches as it appears in the cubital ossa, anterior to the lateral epicondyle o the humerus, between the brachialis and brachioradialis. The posterior cutaneous nerve o the orearm arises rom the radial nerve in the posterior compartment o the arm, as it runs along the radial groove o the humerus. Thus, it reaches the orearm independent o the radial nerve, descending in the subcutaneous tissue o the posterior aspect o the orearm to the wrist, supplying the skin. The supercial branch o the radial nerve is also a cutaneous nerve, but it gives rise to articular branches as well. In the orearm, the radial artery courses between the extensor and the exor muscle groups. Deep dissection o the distal part o the orearm and proximal part o the hand showing the course o the arteries and nerves. The deep branch o the radial nerve, ater it pierces the supinator, runs in the ascial plane between supercial and deep extensor muscles in close proximity to the posterior interosseous artery. It supplies motor innervation to all the muscles with feshy bellies located entirely in the posterior compartment o the orearm (distal to the lateral epicondyle o the humerus). The medial cutaneous nerve o the orearm (medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve) is an independent branch o the medial cord o the brachial plexus. With the posterior cutaneous nerve o the orearm rom the radial nerve, each supplying the area o skin indicated by its name, these three nerves provide all the cutaneous innervation o the orearm. Except or the supercial veins, which oten course independently in the subcutaneous tissue, these neurovascular structures usually exist as components o neurovascular bundles. These bundles are composed o arteries, veins (in the limbs, usually in the orm o accompanying veins), and nerves as well as lymphatic vessels, which are usually surrounded by a neurovascular sheath o varying density. Surace Anatomy o Forearm Three bony landmarks are easily palpated at the elbow: the medial and lateral epicondyles o the humerus and the olecranon o the ulna. Forearm 235 posterolaterally when the orearm is extended, the head o the radius can be palpated distal to the lateral epicondyle. The posterior border o the ulna is subcutaneous and can be palpated distally rom the olecranon along the entire length o the bone. The black dot on the dorsum o the hand indicates the position o the medial epicondyle. The larger radial styloid process can be easily palpated on the lateral side o the wrist when the hand is supinated, particularly when the tendons covering it are relaxed. The radial styloid process is located approximately 1 cm more distal than the ulnar styloid process. This relationship o the styloid processes is important in the diagnosis o certain injuries in the wrist region. Proximal to the radial styloid process, the suraces o the radius are palpable or a ew centimeters. Pain is elt over the lateral epicondyle and radiates down the posterior surace o the orearm. Repeated orceul fexion and extension o the wrist strain the attachment o the common extensor tendon, producing infammation o the periosteum o the lateral epicondyle (lateral epicondylitis). Fracture o Olecranon Fracture o the olecranon, called a "ractured elbow" by laypersons, is common because the olecranon is subcutaneous and protrusive. The typical mechanism o injury is a all on the elbow combined with sudden powerul contraction o the triceps brachii. The ractured olecranon is pulled away by the active and tonic contraction o the triceps. Because o the traction produced by the tonus o the triceps on the olecranon ragment, pinning is usually required. Mallet or Baseball Finger Sudden severe tension on a long extensor tendon may avulse part o its attachment to the phalanx. This deormity results rom the distal interphalangeal joint suddenly being orced into extreme fexion (hyperfexion) when, or example, a baseball is miscaught or a nger is jammed into the base pad. These actions avulse (tear away) the attachment o the tendon to the base o the distal phalanx. Synovial Cyst o Wrist Sometimes a nontender cystic swelling appears on the hand, most commonly on the dorsum o the wrist. The cause o the cyst is unknown, but it may result rom mucoid degeneration (Salter, 1999). Synovial cysts are close to and oten communicate with the synovial sheaths on the dorsum o the wrist (purple in gure). A cystic swelling o the common fexor synovial sheath on the anterior aspect o the wrist can enlarge enough to produce compression o the median nerve by narrowing the carpal tunnel (carpal tunnel syndrome). This syndrome produces pain and paresthesia (partial numbness, burning, or prickling) in the sensory distribution o the median nerve and clumsiness o nger movements (see the clinical box "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome"). High Division o Brachial Artery Sometimes the brachial artery divides at a more proximal level than usual. In this case, the ulnar and radial arteries begin in the superior or middle part o the arm, and the median nerve passes between them. Deep fascia of arm Superfcial Ulnar Artery In approximately 3% o people, the ulnar artery descends supericial to the lexor muscles. This variation must be kept in mind when perorming venesections or withdrawing blood or making intravenous injections. I an aberrant ulnar artery is mistaken or a vein, it may be damaged and produce bleeding. I a pulse cannot be elt, try the other wrist because an aberrant radial artery on one side may make the pulse dicult to palpate. Variations in Origin o Radial Artery the origin o the radial artery may be more proximal than usual; it may be a branch o the axillary or brachial arteries. When a supercial vessel is pulsating near the wrist, it is probably a supercial radial artery. Flexion o the distal interphalangeal joints o the 2nd and 3rd digits is also lost. The ability to fex the metacarpophalangeal joints o the 2nd and 3rd digits is aected because the digital branches o the median nerve supply the 1st and 2nd lumbricals. Thus, when the person attempts to make a st, the 2nd and 3rd ngers remain partially extended ("hand o benediction"). Thenar muscle unction (unction o the muscles at the base o the thumb) is also lost, as in carpal tunnel syndrome (see the clinical box "Carpal Tunnel Syndrome"). When the anterior interosseous nerve is injured, the thenar muscles are unaected, but paresis (partial paralysis) o the fexor digitorum proundus and fexor pollicis longus occurs. When the person attempts to make the "okay" sign, opposing the tip o the thumb and index nger in a circle, a "pinch" posture o the hand results instead owing to the absence o fexion o the interphalangeal joint o the thumb and distal interphalangeal joint o the index nger (anterior interosseous syndrome). Hypesthesia and activity-induced paresthesias Pain Pronator syndrome Pronator Syndrome Pronator syndrome, a nerve entrapment syndrome, is caused by compression o the median nerve near the elbow. The nerve may be compressed between the heads o the pronator teres as a result o trauma, muscular hypertrophy, or brous bands.

Buy generic red viagra 200mg on-line

The arteries to the ductus deerens erectile dysfunction pills cheap 200mg red viagra with mastercard, usually branches o the superior (but requently inerior) vesical arteries, supply the ejaculatory ducts. The umbilical ligaments, like the urinary bladder, are embedded in extraperitoneal or subperitoneal ascia (mostly removed in this dissection). The ejaculatory ducts are ormed by the merger o the duct o the seminal gland and the ductus deerens. The vestigial prostatic utricle, usually seen as an invagination in an anterior view, appears in this posterior dissection as an evagination lying between the ejaculatory ducts. The glandular part makes up approximately two thirds o the prostate; the other third is bromuscular. The fbrous capsule o the prostate is dense and neurovascular, incorporating the prostatic plexuses o veins and nerves. Pelvic part o ureters, urinary bladder, seminal glands, terminal parts o ductus deerens, and prostate. The let seminal gland and ampulla o the ductus deerens are dissected ree and sliced open. The perineal membrane lies between the external genitalia and the deep part o the perineum (anterior recess o ischio-anal ossa). It is pierced by the urethra, ducts o the bulbo-urethral glands, dorsal and deep arteries o the penis, cavernous nerves, and the dorsal nerve o the penis. The anterior surace is separated rom the pubic symphysis by retroperitoneal at in the retropubic space. Although not clearly distinct anatomically, the ollowing lobes o the prostate are traditionally described. It is bromuscular, the muscle bers representing a superior continuation o the external urethral sphincter muscle to the neck o the bladder, and contains little, i any, glandular tissue. Right and let lobes o the prostate, separated anteriorly by the isthmus and posteriorly by a central, shallow longitudinal urrow, may each be subdivided or descriptive purposes into our indistinct lobules dened by their relationship to the urethra and ejaculatory ducts and-although less apparent-by the arrangement o the ducts and connective tissue: 1. An ineroposterior (lower posterior) lobule that lies posterior to the urethra and inerior to the ejaculatory ducts. This lobule constitutes the aspect o the prostate palpable by digital rectal examination. An inerolateral (lower lateral) lobule directly lateral to the urethra, orming the major part o the right or let lobe. A superomedial lobule, deep to the ineroposterior lobule, surrounding the ipsilateral ejaculatory duct. An anteromedial lobule, deep to the inerolateral lobule, directly lateral to the proximal prostatic urethra. This region tends to undergo hormone-induced hypertrophy in advanced age, orming a middle lobule that lies between the urethra and the ejaculatory ducts and is closely related to the neck o the bladder. Enlargement o the middle lobule is believed to be at least partially responsible or the ormation o the uvula (L. Lobules and zones o prostate demonstrated by anatomical section and ultrasonographic imaging. The ducts o the glands in the peripheral zone open into the prostatic sinuses, whereas the ducts o the glands in the central (internal) zone open into the prostatic sinuses and the seminal colliculus. Prostatic fuid, a thin, milky fuid, provides approximately 20% o the volume o semen (a mixture o secretions produced by the testes, seminal glands, prostate, and bulbo-urethral glands that provides the vehicle by which sperms are transported) and plays a role in activating the sperms. The prostatic arteries are mainly branches o the internal iliac artery (see Table 6. This prostatic venous plexus, between the brous capsule o the prostate and the prostatic sheath, drains into the internal iliac veins. The ducts o the bulbourethral glands pass through the perineal membrane with the intermediate urethra and open through minute apertures into the proximal part o the spongy urethra in the bulb o the penis. They traverse the paravertebral ganglia o the sympathetic trunks to become components o lumbar (abdominopelvic) splanchnic nerves and the hypogastric and pelvic plexuses. Presynaptic parasympathetic bers rom S2 and S3 spinal cord segments traverse pelvic splanchnic nerves, which also join the inerior hypogastric/pelvic plexuses. Synapses with postsynaptic sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons occur within the plexuses, en route to or near the pelvic viscera. As part o an orgasm, the sympathetic system stimulates contraction o the internal urethral sphincter to prevent retrograde ejaculation. Simultaneously, it stimulates rapid peristalticlike contractions o the ductus deerens, and the combined contraction o and secretion rom the seminal glands and prostate that provide the vehicle (semen), and the expulsive orce to discharge the sperms during ejaculation. The unction o the parasympathetic innervation o the internal genital organs is unclear. However, parasympathetic bers traversing the prostatic nerve plexus orm the cavernous nerves that pass to the erectile bodies o the penis, which are responsible or producing penile erection. During this procedure, part o the ductus deerens is ligated and/or excised through an incision in the superior part o the scrotum. Hence, the subsequent ejaculated fuid rom the seminal glands, prostate, and bulbo-urethral glands contains no sperms. The unexpelled sperms degenerate in the epididymis and the proximal part o the ductus deerens. The ends o the sectioned ductus deerentes are reattached under an operating microscope. Abscesses in Seminal Glands Localized collections o pus (abscesses) in the seminal glands may rupture, allowing pus to enter the peritoneal cavity. Seminal glands can be palpated during a rectal examination, especially i enlarged or ull. They can also be massaged to release their secretions or microscopic examination to detect gonococci (organisms that cause gonorrhea), or example. The middle lobule usually enlarges the most and obstructs the internal urethral oriice. The prostate is examined or enlargement and tumors (ocal masses or asymmetry) by digital rectal examination. A ull bladder oers resistance, holding the gland in place and making it more readily palpable. Because o the close relationship o the prostate to the prostatic urethra, obstructions may be relieved endoscopically. The instrument is inserted transurethrally through the external urethral orice and spongy urethra into the prostatic urethra. In more serious cases, the entire prostate is removed along with the seminal glands, ejaculatory ducts, and terminal parts o the deerent ducts (radical prostatectomy). The distal portion o the ductus is superfcial within the scrotum (and, thereore, easily accessible or deerentectomy or vasectomy) beore it penetrates the anterior abdominal wall via the inguinal canal. The pelvic portion o the ductus lies immediately external to the peritoneum, with its terminal portion enlarging externally as its lumen becomes tortuous internally, orming the ampulla o the ductus deerens. Seminal glands, ejaculatory ducts, and prostate: Obliquely placed seminal glands converge at the base o the bladder, where each o their ducts merges with the ipsilateral ductus deerens to orm an ejaculatory duct. The two ejaculatory ducts immediately enter the posterior aspect o the prostate, running closely parallel through the gland to open on the seminal colliculus. The seminal glands and prostate produce by ar the greatest portion o the seminal uid, indispensable or transport and delivery o sperms. These internal genital organs, located within the anterior male pelvis, receive blood rom the inerior vesicle and middle rectal arteries, which drain into the continuous prostatic/vesicle venous plexus. Sympathetic fbers rom lumbar levels stimulate the contraction and secretion resulting in ejaculation. In prepubertal emales, the connective tissue capsule (tunica albuginea o the ovary) comprising the surace o the ovary is covered by a smooth layer o ovarian mesothelium or surace (germinal) epithelium, a single layer o cuboidal cells that gives the surace a dull, grayish appearance, contrasting with the shiny surace o the adjacent peritoneal mesovarium with which it is continuous.

Generic red viagra 200 mg otc

Consequently impotence at 16 proven 200 mg red viagra, when visceral aerent ibers are stimulated by stretching, the bladder contracts relexively, the internal urethral sphincter relaxes (in males), and urine lows into the urethra. With toilet training, we learn to suppress this relex when we do not wish to void. The sympathetic innervation that stimulates ejaculation simultaneously causes contraction o the internal urethral sphincter, to prevent relux o semen into the bladder. Sensory bers rom most o the bladder are visceral; refex aerents ollow the course o the parasympathetic bers, as do those transmitting pain sensations. The superior surace o the bladder is covered with peritoneum and thereore is superior to the pelvic pain line (see Table 6. The intramural and prostatic parts o the urethra are supplied by prostatic branches o the inerior vesical and middle rectal arteries. The veins rom the proximal two parts o the urethra drain into the prostatic venous plexus. The nerves are derived rom the prostatic plexus (mixed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and visceral aerent bers). The prostatic plexus is one o the pelvic plexuses (an inerior extension o the vesical plexus) arising as organ-specic extensions o the inerior hypogastric plexus. The distal intermediate part and spongy urethra will be described urther with the perineum. The intramural (preprostatic) part o the urethra varies in diameter and length, depending on whether the bladder is lling. During lling, the neck o the bladder is tonically contracted so the internal urethral orice is small and high. The most prominent eature o the prostatic urethra is the urethral crest, a median ridge between bilateral grooves, the prostatic sinuses. The seminal colliculus is a rounded eminence in the middle o the urethral crest with a slit-like orice that opens into a small cul-de-sac, the prostatic utricle. The utricle is the vestigial remnant o the embryonic uterovaginal canal, the surrounding walls o which, in the emale, constitute the primordium o the uterus and a part o the vagina (Moore et al. The ejaculatory ducts open into the prostatic urethra via minute, slit-like openings located adjacent to and occasionally just within the orice o the prostatic utricle. The emale urethra (approximately 4 cm long and 6 mm in diameter) passes antero-ineriorly rom the internal urethral orice o the urinary bladder. The musculature surrounding the internal urethral orice o the emale bladder is not organized into an internal sphincter. The emale external urethral orifce is located in the vestibule o the vagina, the clet between the labia minora o the external genitalia, directly anterior to the vaginal orice (ostium). The urethra lies anterior to the vagina (orming an elevation in the anterior vaginal wall; see. One group o glands on each side, the para-urethral glands, are homologs to the prostate. These glands have a common para-urethral duct, which opens (one on each side) near the external urethral orice. Blood is supplied to the emale urethra by the internal pudendal and vaginal arteries. The nerves to the urethra arise rom the vesical (nerve) plexus and the pudendal nerve. Visceral aerents rom most o the urethra run in the pelvic splanchnic nerves, but the termination receives somatic aerents rom the pudendal nerve. A portion o the posterior wall o the bladder has been removed to reveal the intramural part o ureter and the ductus deerens posterior to the bladder. The interureteric old runs between the entrances o the ureters into the bladder lumen, demarcating the superior limit o the trigone o the bladder. The prominence o the posterior wall o the internal urethral orifce (at the tip o the leader line indicating this orifce), when exaggerated, becomes the uvula o the bladder. This enlarged detail o the boxed area in (A) demonstrates the bulbo-urethral glands embedded in the substance o the external urethral sphincter. The sigmoid colon is intraperitoneal, suspended by the sigmoid mesocolon, but the rectum becomes retroperitoneal and then subperitoneal as it descends. The peritoneum has been removed superior to sacral promontory and right iliac ossa, revealing the superior hypogastric plexus lying in the biurcation o the abdominal aorta and the internal iliac artery, ureter, and ductus deerens crossing the pelvic brim to enter the lesser pelvis. At this point, the teniae coli o the sigmoid colon spread to orm a continuous outer longitudinal layer o smooth muscle, and the atty omental appendices are discontinued. The rectum ollows the curve o the sacrum and coccyx, orming the sacral exure o the rectum. The rectum ends anteroinerior to the tip o the coccyx, immediately beore a sharp postero-inerior angle (the anorectal exure o the anal canal) that occurs as the gut perorates the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani). With the fexures o the rectosigmoid junction superiorly and the anorectal junction ineriorly, the rectum has an S shape when viewed laterally. Three sharp lateral exures o the rectum (superior and inerior on the let side and intermediate on the right) are apparent when the rectum is viewed anteriorly. The fexures are ormed in relation to three internal inoldings (transverse rectal olds): two on the let side and one on the right side. The dilated terminal part o the rectum, lying directly superior to and supported by the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani) and anococcygeal ligament, is the ampulla o the rectum. The ampulla receives and holds an accumulating ecal mass until it is expelled during deecation. The ability o the ampulla to relax to accommodate the initial and subsequent arrivals o ecal material is another essential element o maintaining ecal continence. Peritoneum covers the anterior and lateral suraces o the superior third o the rectum, only the anterior surace o the middle third, and no surace o the inerior third because it is subperitoneal (see Table 6. In males, the peritoneum refects rom the rectum to the posterior wall o the bladder, where it orms the foor o the rectovesical pouch. In emales, the peritoneum refects rom the rectum to the posterior part o the ornix o the vagina, where it orms the foor o the recto-uterine pouch. In both sexes, lateral refections o peritoneum rom the superior third o the rectum orm pararectal ossae. Despite their name, the inerior rectal arteries, which are branches o the internal pudendal arteries, mainly supply the anal canal. The three sharp lateral exures o the rectum reect the way in which the lumen navigates the transverse rectal olds (shown in part B) on the internal surace. This coronal section o the rectum and anal canal demonstrates the arterial supply and venous drainage. The internal and external rectal venous plexuses are most directly related to the anal canal. In males, the rectum is related anteriorly to the undus o the urinary bladder, terminal parts o the ureters, ductus deerentes, seminal glands, and prostate. The rectovesical septum lies between the undus o the bladder and the ampulla o the rectum and is closely associated with the seminal glands and prostate. In emales, the rectum is related anteriorly to the vagina and is separated rom the posterior part o the ornix and the cervix by the recto-uterine pouch. Inerior to this pouch, the weak rectovaginal septum separates the superior hal o the posterior wall o the vagina rom the rectum. Because the superior rectal vein drains into the portal venous system and the middle and inerior rectal veins drain into the systemic system, these anastomoses are clinically important areas o portocaval anastomosis. The submucosal rectal venous plexus surrounds the rectum, communicating with the vesical venous plexus in males and the uterovaginal venous plexus in emales. Although these plexuses bear the term rectal, they are primarily "anal" in terms o location, unction, and clinical signicance (see "Venous and Lymphatic Drainage o Anal Canal"). The right and let middle rectal arteries, which oten arise rom the anterior divisions o the internal iliac arteries in the pelvis, supply the middle and inerior parts o the rectum.

Buy discount red viagra on-line

The majority o the thoracic cavity is occupied by the lungs impotence zargan cheap 200 mg red viagra overnight delivery, which provide or the exchange o oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air and blood. Most o the remainder o the thoracic cavity is occupied by the heart and structures involved in conducting the air and blood to and rom the lungs. Also, the esophagus, a tubular structure carrying nutrients (ood) to the stomach, traverses the thoracic cavity. In terms o unction and development, the breasts are related to the reproductive system; however, the breasts are located on and typically dissected with the thoracic wall and thereore are included in this chapter. The anterolateral axio-appendicular muscles (see Chapter 3, Upper Limb) that overlie the thoracic cage and orm the bed o the breast are encountered in the thoracic wall and may be considered part o it but are distinctly upper limb muscles based on unction and innervation. The domed shape o the thoracic cage provides remarkable rigidity, given the light weight o its components, enabling it to perorm the ollowing unctions: Protect vital thoracic and abdominal organs (most air or fuid lled) rom external orces. Resist the negative (subatmospheric) internal pressures generated by the elastic recoil o the lungs and inspiratory movements. Provide the anchoring attachment (origin) o many o the muscles that move and maintain the position o the upper limbs relative to the trunk, as well as provide the attachments or muscles o the abdomen, neck, back, and respiration. Although the domed shape o the thoracic cage provides rigidity, its joints and the thinness and fexibility o the ribs allow it to absorb external blows and compressions without racture and to change its shape or respiration. Because the most important structures within the thorax (heart, great vessels, lungs, and trachea), as well as its foor and walls, are constantly in motion, the thorax is one o the most dynamic regions o the body. With each breath, the muscles o the thoracic wall, working in concert with the diaphragm and muscles o the abdominal wall, vary the volume o the thoracic cavity. This is accomplished rst by expanding the capacity o the cavity, thereby causing the lungs to expand and draw air in, and then, due to lung elasticity and muscle relaxation, decreasing the volume o the cavity and causing them to expel air. The shape and size o the thoracic cavity and thoracic wall are dierent rom that o the chest (upper trunk or torso) because the latter includes some proximal upper limb bones and muscles and, in adult emales, the breasts. The thorax includes the primary organs o the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The thoracic cavity is divided into three compartments: the central mediastinum, occupied by the heart and structures transporting air, blood, and ood; and the right and let pulmonary cavities, occupied by the lungs. The mammary glands o the breasts lie within the subcutaneous tissue o the (continued on p. The osteocartilaginous thoracic cage includes the sternum, 12 pairs o ribs and costal cartilages, and 12 thoracic vertebrae and intervertebral discs. The clavicles and scapulae orm the pectoral (shoulder) girdle, one side o which is included here to demonstrate the relationship between the thoracic (axial) and upper limb (appendicular) skeletons. The red dotted line indicates the position o the diaphragm, which separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Thoracic Wall 293 Skeleton o Thoracic Wall the thoracic skeleton orms the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage. The ribs and costal cartilages orm the largest part o the thoracic cage; both are identied numerically, rom the most superior (1st rib or costal cartilage) to the most inerior (12th). It has a single acet on its head or articulation with T1 vertebra only and two transversely directed grooves crossing its superior surace or the subclavian vessels. The 2nd rib has a thinner, less curved body and is substantially longer than the 1st rib. By closing the inerior thoracic aperture, the diaphragm separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities almost completely. Structures passing rom the thorax to the abdomen, or vice versa, pass through openings that traverse the diaphragm. Just as the size o the thoracic cavity (or its contents) is oten overestimated, its inerior extent (corresponding to the boundary between the thoracic and abdominal cavities) is oten incorrectly estimated because o the discrepancy between the inerior thoracic aperture and the location o the diaphragm (foor o the thoracic cavity) in living persons. Although the diaphragm takes origin rom the structures that make up the inerior thoracic aperture, the domes o the diaphragm rise as high as the level o the 4th intercostal space, and abdominal viscera, including the liver, spleen, and stomach, lie superior to the plane o the inerior thoracic aperture, within the thoracic wall. Joints o Thoracic Wall Although movements o the joints o the thoracic wall are requent-or example, in association with normal respiration- the range o movement at the individual joints is relatively small. Nonetheless, any disturbance that reduces the mobility o these joints intereres with respiration. During deep breathing, the excursions o the thoracic cage (anteriorly, superiorly, or laterally) are considerable. The type, participating articular suraces, and ligaments o the joints o the thoracic wall are provided in Table 4. The intervertebral joints between the bodies o adjacent vertebrae are joined by longitudinal ligaments and A typical rib articulates posteriorly with the vertebral column at two joints, the joints o heads o ribs and costotransverse joints. The heads o the ribs connect so closely to the vertebral bodies that only slight gliding movements occur at the (demi)acets (pivoting around the intra-articular ligament o the head o the rib). Abundant ligaments lateral to the posterior parts (vertebral arches) o the vertebrae provide strength to and limit the movements o these joints, which have only thin joint capsules. A costotransverse ligament passing rom the neck o the rib to the transverse process and a lateral costotransverse ligament passing rom the tubercle o the rib to the tip o the transverse process strengthen the anterior and posterior aspects o the joint, respectively. A superior costotransverse ligament is a broad band that joins the crest o the neck o the rib to the transverse process superior to it. The aperture between this ligament and the vertebra permits passage o the spinal nerve and the posterior branch o the intercostal artery. The strong costotransverse ligaments binding these joints limit their movements to slight gliding. However, the articular suraces on the tubercles o the superior 6 ribs are convex and it into concavities on the transverse processes. As a result, rotation occurs around a mostly transverse axis that traverses the intra-articular ligament and the head and neck o the rib. This results in elevation and depression movements o the sternal ends o the ribs and sternum in the sagittal plane (pump-handle movement). The weak joint capsules o these joints are thickened anteriorly and posteriorly to orm radiate sternocostal ligaments. These continue as thin, broad membranous bands passing rom the costal cartilages to the anterior and posterior suraces o the sternum, orming a elt-like covering or this bone. Movements o Thoracic Wall Movements o the thoracic wall and the diaphragm during inspiration produce increases in the intrathoracic volume and diameters o the thorax. Consequent pressure changes result in air being alternately drawn into the lungs (inspiration) through the nose, mouth, larynx, and trachea and expelled rom the lungs (expiration) through the same passages. During passive expiration, the diaphragm, intercostal muscles, and other muscles relax, decreasing intrathoracic volume and increasing the intrathoracic pressure. This allows the stretched elastic tissue o the lungs to recoil, expelling most o the air. The vertical dimension (height) o the central part o the thoracic cavity increases during inspiration as contraction o the diaphragm causes it to descend, compressing the abdominal viscera. During expiration, the vertical dimension returns to the neutral position as the elastic recoil o the lungs produces subatmospheric pressure in the pleural cavities, between the lungs and the thoracic wall. As a result o this and the absence o resistance to the previously compressed viscera, the domes o the diaphragm ascend, diminishing the vertical dimension. Because the ribs slope ineriorly, their elevation also results in anteroposterior movement o the sternum, especially its inerior end, with slight movement occurring at the manubriosternal joint in young people, in whom this joint has not yet synostosed (united). The transverse dimension o the thorax also increases slightly when the intercostal muscles contract, raising the middle (lateralmost parts) o the ribs (especially the lower ones)-the bucket-handle movement. The combination o all these movements moves the thoracic cage anteriorly, superiorly, and laterally. The middle parts o the lower ribs move laterally when they are elevated, increasing the transverse dimension (bucket-handle movement).