Order 60caps confido with mastercard

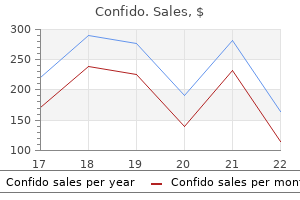

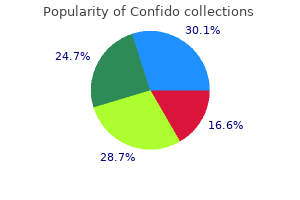

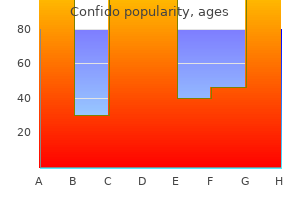

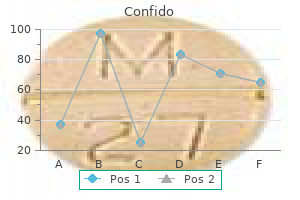

The diagnosis prostate yeast symptoms purchase confido 60 caps online, assessment and surgery are fraught with uncertainties and are best left to those with a well-developed interest in this problem. Pectus excavatum Other diseases of the chest wall Congenital abnormalities are often incidental findings on chest radiography. Cervical rib and thoracic outlet syndrome this rib is usually represented by a fibrous band originating from the seventh cervical vertebra and inserting onto the first thoracic rib. It may be asymptomatic, but because the sub- the sternum is depressed, with a dish-shaped deformity of the anterior portions of the ribs on one or both sides. It can be repaired to improve its cosmetic appearance either as an open procedure (the Ravitch procedure) which involves resecting the affected costal cartilages and mobilising the sternum, or as a minimally invasive technique, the Nuss procedure. It often comes to light during the growth spurt at adolescence when, of course, the teenager is particularly sensitive about appearance. Most patients are asymptomatic and the only justification for treatment is on cosmetic grounds. Some surgeons make a very good case for this but the risk of morbidity and of a less than perfect result must be clearly spelt out to the patient and his/her parents. Surgery involves mobilising the sternum with the costal cartilages so that the sternum can be flattened to a more anatomical position. Surgery is best left until the late teens, when further growth of the chest wall is unlikely. Much of this is due to the effects of atheroma on the arteries supplying the heart muscle (coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction) and brain (stroke), although atheroma is also common at other sites. This article addresses diseases that are typically the province of the vascular surgeon, namely those affecting the peripheral arterial system: vascular disease that alters the normal structure and function of the aorta, its visceral branches and the arteries of the lower extremity. Stenosis or occlusion produces symptoms and signs that are related to the organ supplied by the artery. The pain is exacerbated by lying down or elevation of the foot due to loss of the gravitational effects on perfusion pressure in the foot. The patient characteristically describes pain that is worse at night and may be lessened by hanging the foot out of bed or by sleeping in a chair (effects of gravity restored). Ulceration and gangrene Ulceration occurs with severe arterial insufficiency and may present as painful erosion between toes or as shallow, non-healing ulcers on the dorsum of the feet, on the shins and especially around the malleoli. Left superficial femoral occlusion with collateral vessels present, causing claudication. Features of chronic arterial stenosis or occlusion in the leg Intermittent claudication Intermittent claudication occurs as a result of anaerobic muscle metabolism and is classically described as debilitating cramp-like pain felt in the muscles that is: Colour, temperature, sensation and movement Unlike an acutely ischaemic foot that is often cold, white, paralysed and insensate, a chronically ischaemic limb tends to equilibrate with the temperature of its surroundings and may feel quite warm under the bedclothes. Patients with critical limb ischaemia who have been waiting for a consultation with their leg in dependence may have a red swollen foot that may be mistaken for cellulitis by the unwary clinician. The capillary refill time may be elicited by pressing the skin of the heel or toe causing blanching reliably brought on by walking; not present on taking the first step (unlike osteoarthritis); reliably relieved by rest both in the standing and sitting positions; usually within 5 minutes (unlike nerve compression from a lumbar intervertebral disc prolapse or osteoarthritis of the spine or spinal stenosis, which are typically relieved only when resting in the sitting position for greater than 5 minutes). The distance that a patient is able to walk without stopping varies (claudication distance) only slightly from day to day. It is decreased by increasing the work demands and hence oxygen requirements of the muscles affected. The muscle group affected by claudication is classically one anatomical level below the level of arterial disease and is usually felt in the calf because the superficial femoral artery is the most commonly affected artery (70% of cases). Diminution of a femoral and/or popliteal pulse can often be appreciated by comparing it with its opposite number; however, pedal pulses are either clinically palpable or absent. Popliteal pulses are often difficult to feel; a popliteal artery aneurysm should be suspected if the popliteal pulse is prominent with concomitant loss of the natural concavity of the popliteal fossa. In this case, exercise (walking until claudication develops) usually causes the pulse to disappear as vasodilation occurs below the obstruction, causing the pulse pressure to reduce. An arterial bruit, heard on auscultation over the pulse, indicates turbulent flow and suggests a stenosis. Aortoiliac obstruction Claudication in buttocks, thighs and calves Femoral and distal pulses absent in both limbs Bruit over aortoiliac region Impotence (Leriche) Iliac obstruction Unilateral claudication in the thigh and calf and sometimes the buttock Bruit over the iliac region Unilateral absence of femoral and distal pulses Femoropopliteal obstruction Distal obstruction Unilateral claudication in the calf Femoral pulse palpable with absent unilateral distal pulses Femoral and popliteal pulses palpable Ankle pulses absent Claudication in calf and foot Relationship of clinical findings to site of disease In most cases the site of arterial obstruction can be determined from the symptoms and signs (Table 56. Severe ischaemia (rest pain, ulceration, gangrene) is usually caused by multilevel disease. When further investigation is indicated, the purpose is to confirm the presence and severity of peripheral arterial disease, identify the anatomical location of disease and assess the suitability of the patient for intervention. Many patients have other age-related diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and malignancy, that may impact on both their symptoms and suitability for intervention. Blood tests to exclude anaemia, diabetes, renal disease and lipid abnormalities should include a full blood count, blood glucose, lipid profile and serum urea and electrolytes. High blood viscosity (polycythaemia and thrombocythaemia) may be caused by smoking but may also be associated with cancer; renal impairment (raised serum creatinine and low estimated glomerular filtration rate) may be caused by drugs and may be exacerbated by intravenous contrast agents used during angiography. Arterial blood gases and pulmonary function test may be appropriate in patients with severe lung disease. A continuous-wave ultrasound signal is transmitted from the probe at an artery, and a receiver within the probe itself picks up the reflected beam. The change in frequency in the reflected beam compared with that of the transmitted beam is due to the Doppler shift, resulting from the reflection of the beam by moving blood cells. The frequency change may be converted into an audio signal that is typically pulsatile. Doppler ultrasound equipment can be used in conjunction with a sphygmomanometer to assess systolic pressure in small vessels. Both the pressure and signal quality are important; a normal artery has a triphasic signal that can be detected by a trained observer. However, although the presence of a Doppler signal indicates moving blood, it does not necessarily indicate that the blood flow is sufficient to maintain limb viability and prevent limb loss. The highest pressure in the dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial or peroneal artery serves as the numerator, with the highest brachial systolic pressure being the denominator. The image is created because of the varying ability of different tissues to reflect the ultrasound beam. A second ultrasound beam is then used to insonate the imaged vessel and the Doppler shift obtained is analysed by a computer. Most scanners now have colour coding, which allows detailed visualisation of blood flow, turbulence, etc. Different colours indicate changes in direction and velocity of flow, with areas of high flow usually indicating a stenosis. In experienced hands, duplex scanning is as accurate as angiography and has the advantages of cost-effectiveness and safety. However, the aortoiliac segment can be difficult to visualise particularly in obese patients. The images obtained are digitalised by computer and the extraneous background (bone, soft tissues, etc. Furthermore, it is relatively expensive compared to other investigation modalities and its usage should be limited to patients in whom a concomitant intervention is predicted. They can be useful where duplex scanning is not possible (intrathoracic arteries) or produces poor images (aortoiliac segment). For patients with rest pain or tissue necrosis, intervention is usually required to prevent major amputation. Similarly, one-quarter of patients with claudication have significant atherosclerotic disease affecting their carotid and renal arterial systems. It is thus not surprising that the risk of suffering a major cardiovascular event per year in patients with claudication is >5%, and that 50% of claudicants will die within 10 years from myocardial infarction or stroke. The common modifiable risk factors for peripheral arterial disease mirror those for coronary artery disease: smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.

Buy genuine confido

A limb is deadly when the putrefaction and infection of moist gangrene spreads to surrounding viable tissues mens health august 2013 buy generic confido pills. Other life-threatening situations for which amputation may be required include gas gangrene (as opposed to simple infection), neoplasm (such as osteogenic sarcoma) and arteriovenous fistula. For less extensive gangrene, if amputation is taken through a joint, healing is improved by removing the cartilage from the joint surface. A transmetatarsal amputation may be required when several toes are affected but the proximal circulation is adequate. Major amputation Choice of operation the major choice is between an above- and below-knee operation. A below knee amputation preserves the knee joint and gives the best chance of walking again with a prosthesis. However, an above knee amputation is more likely to heal and may be appropriate if the patient has no prospect of walking again. Unfortunately, the presence of a femoral pulse does not guarantee healing of a below-knee amputation, and sometimes a failed below-knee amputation may require revision to an above-knee procedure. For above- or below-knee amputations with a good stump shape, it is possible to hold a prosthesis in place simply by suction, without any cumbersome and unsightly straps. Gangrene Deadly limb Wet gangrene Spreading cellulitis Arteriovenous fistula Other. However, if the metatarsophalangeal joint region is involved, a ray excision is required, taking part of the corresponding metatarsal bone and cutting tendons back. For both methods, the total length of flap must be at least one and a half times the diameter of the leg at the point of bone section. The long posterior flap technique is the older method and remains the more popular, probably because of its relative simplicity. The proposed incision should be marked carefully: the tibial tuberosity identified and a distance 10 cm measured distally and marked with a sterile marker pen; this is the anterior landmark. The circumference is measured at this landmark with a long suture tie and this length divided into two thirds. The suture is centred over the anterior landmark so that there is one-third either side. The line of incision is now extended transversely around the back of the limb to join the distal extent of the longitudinal incisions. An incision is then made along the previously measured and marked lines through skin, subcutaneous fat and deep fascia. Anteriorly, the incision is deepened to bone and the lateral and posterior incisions are fashioned to leave the bulk of the gastrocnemius muscle attached to the flap, muscle and skin being transected together at the same level. Nerves are not clamped but pulled down gently and sharply transected as high as possible. The fibula is divided 2 cm proximal to the level of tibial division using bone cutters. The tibia is cleared and transected at the desired level, the anterior aspect of the bone being sawn obliquely before the cross-cut is made. This, with filing, gives a smooth anterior bevel, which prevents pressure necrosis of the flap. The area is washed with saline to remove bone fragments and the muscle and fascia are sutured with an absorbable material to bring the flap over the bone ends. The skew flap amputation makes use of anatomical knowledge of the skin blood supply. After division of bone and muscle in a fashion similar to that described above, the gastrocnemius myoplastic flap is sutured over the cut bone end to the anterior tibial periosteum with absorbable sutures. Finally, drainage and skin sutures are inserted and the limb dressed as for the long posterior flap operation. Through-knee amputation More recently through-knee or knee disarticulation has regained popularity as an alternative to above-knee amputation if soft-tissue viability permits. This amputation preserves the full length of the femur and patella, providing a long mechanical lever that is controlled by stronger muscles as the line of muscle transection is distal and occurs through fascial tissue, as opposed to thick muscular bellies as is the case with an above-knee amputation. The bulbous nature of the amputation end, initially thought a hindrance for subsequent prosthetic fitting, is now seen as beneficial as it allows for a self-suspending prosthetic that is less likely to rotate compared to an above-knee amputation prosthetic. The line of incision is marked preoperatively: equal anterior and posterior semicircular flaps are constructed, with the proximal extent of incision being the joint line laterally and medially, and the distal extent of the anterior flap being 3 cm below the tibial tuberosity and directly posterior to this level for the posterior flap. The anterior incision is carried down to the tibia and the patellar tendon insertion into the tibial tuberosity is identified and released. The patellar tendon is followed proximally to the patella, releasing it from surrounding fascial structures. The anterior knee capsule is entered and the lateral and medial capsule divided along with the collateral knee ligaments. The medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle along with its vascular pedicle is transected 3 cm below the tibial plateau. The lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle is divided at the level of the knee joint. The popliteal artery and vein are ligated distal to the medial head of gastrocnemius pedicle origin. The posterior flap incision is now carried through to join the anterior dissection and the limb is removed. The menisci do not need to be removed but can be trimmed to provide a smooth surface. With the hip flexed the patellar tendon is pulled down and sutured to the posterior cruciate ligament with polypropylene, restoring the normal position of the patellar tendon between the femoral condyles. The residual head of gastrocnemius is retroflexed and sutured to the knee capsule, to provide a covering of the femur and reduce synovial fluid drainage. A suction drain is applied to the muscle bed and the skin flaps closed with skin clips or sutures Above-knee amputation the site is chosen as indicated above but may need to be higher if bleeding is poor on incision of the skin. Equal curved anterior and posterior skin flaps are made of sufficient total length. The sciatic nerve is pulled down and transected cleanly, as high as possible, and the accompanying artery ligated. The muscle ends are united over the bone by absorbable sutures incorporating the fascia. A suction drain deep to the muscle is brought out through the skin clear of the wound. The fascia and subcutaneous tissues are further brought together so that the skin can be apposed by interrupted sutures. Care of the good limb must not be forgotten, as a pressure ulcer on the remaining foot will delay mobilisation despite satisfactory healing of the stump. Early assessment of the home is part of the programme; it allows time for minor alterations, such as the addition of stair rails, movement of furniture to give support near doors and provision of clearance in confined passages. They can either be true aneurysms, containing the three layers of the arterial wall (intima, media, adventitia) in the aneurysm sac, or false aneurysms, having a single layer of fibrous tissue as the wall of the sac. Aneurysms can also be grouped according to their shape (fusiform, saccular) or their aetiology (atheromatous, traumatic, mycotic, etc. The term mycotic is a misnomer because, although it indicates infection as the cause of the aneurysm, it is due to bacteria, not fungi. Aneurysms may occur in the aorta, iliac, femoral, popliteal, subclavian, axillary, carotid, cerebral, mesenteric, splenic and renal arteries and their branches. Complications Early complications include haemorrhage, which requires return to the operating room for haemostasis; haematoma, which requires evacuation; and infection, usually in association with a haematoma. Wound dehiscence and gangrene of the flaps are caused by ischaemia; a higher amputation may be necessary. Amputees are at risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the early postoperative period and prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin is essential. Later complications include pain resulting from unresolved infection (sinus, osteitis, sequestrum), a bone spur, a scar adherent to bone and an amputation neuroma. Patients frequently remark that they can feel the amputated limb (phantom limb) and sometimes remark that it is painful (phantom pain). Other late complications include ulceration of the stump because of pressure effects of the prosthesis or increased ischaemia.

Discount confido express

Isolated fractures of the ulna prostate cancer wristbands cheap confido 60 caps with mastercard, the so-called nightstick fracture, are a little more controversial, as non-operative management is possible but in this location risks delayed union and non-union, hence treatment depends on patient factors. Operative fixation with plate and screw fixation is technically simple and allows early predictable return to function. Undisplaced fractures <2 mm gap or step at the articular surface can be treated non-operatively. In displaced fractures the extensor mechanism is interrupted and the articular surface requires anatomical reduction and stable fixation to allow early movement. Fixation may comprise K-wire and figure-ofeight tension band wiring or plate fixation. In multifragmentary fractures or fractures associated with an elbow dislocation, increased stability is required with the use of a plate and screws. This fracture could not be controlled by non-operative means and was treated with lag screws protected by a plate. Treatment of a humeral shaft fracture with a concomitant radial nerve palsy remains topical. In general, if the nerve injury occurs at the time of the original injury, non-operative treatment can be considered. If it occurs after the injury, for example at the time of brace application, then it should be explored. When exploring the radial nerve, plate and screw fixation is then undertaken to stabilise the humerus. Internal fixation with an intramedullary device or plate and screw construct can restore length, alignment and rotation. This can improve the speed and amount of functional restoration, but carries all the risks of surgical treatment. Proximal femoral fractures the blood supply to the femoral head is a prime consideration in treating femoral neck fractures. The joint capsule anteriorly inserts along the intertrochanteric line and posteriorly half way along the femoral neck. Fractures proximal to the hip capsule are intracapsular and those distal to the capsule are extracapsular fractures. Fractures of the proximal humerus In fractures of the proximal humerus consideration is given to the vascularity of the humeral head. The most common classification of the proximal humerus is the Neer classification looking at the four individual pieces of the proximal humerus (articular head fragment, lesser tuberosity, greater tuberosity and the shaft). If a fragment is displaced by more than 1 cm or angulated by more than 45 degrees in respect of another fragment, it is considered a part. As such, based on the fracture pattern, it may be undisplaced, 2 part, 3 part or 4 part. Consideration is then given to potential joint dislocation, anterior or posterior. The greater the number of parts, the higher the chances of interruption of the vascularity to the humeral head and the more complex the injury. Three factors can be used to predict avascularity of the humeral head: Intracapsular femoral neck fractures Intracapsular fractures are further broken down into whether they are displaced or undisplaced. Undisplaced intracapsular fractures are generally stable and interruption of the blood supply to the femoral head is rare. Therefore, treatment is aimed at ensuring the head fragment does not displace during rehabilitation. This can be achieved with cannulated screws inserted along the femoral neck into the head. A displaced intracapsular fracture disrupts the blood supply to the femoral head and risks avascular necrosis. If the patient is physiologically young, reduction and internal fixation with cannulated screws or a dynamic hip screw might be attempted to preserve the native head. If the patient is older and would benefit from a single operation, then the head may be sacrificed and replaced with a prosthetic head. With displaced fractures, where the head is avascular, occurring in older patients who may have osteoporosis and other co-morbidities, consideration may be given to replacing the humeral head. One of the limitations of trauma hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures involves reliable healing of the tuberosities and the rotator cuff. This implant does not rely on tuberosity healing, as it functions under the power of the deltoid muscle. A variety of fixation methods are available: percutaneous fixation, intramedullary nails and plate fixation. Extracapsular femoral neck fractures If the fracture is extracapsular, vascularity of the head is not an issue. Unstable fractures include a reverse oblique pattern or where the medial calcar is comminuted (lesser trochanter) fracture. In unstable fractures a dynamic hip screw can also be used, but due to the unfavourable mechanical environment relating to the loss of the medial calcar or a reverse oblique pattern, an intramedullary device might be considered. Clavicle fractures Diaphyseal fractures of the middle third of the clavicle have traditionally been treated non-operatively with a broad arm sling for comfort and social protection, followed by increasing use of the arm. There is, however, a subset of clavicle fractures that may be slow to heal and that do impact on shoulder girdle function. Displaced, comminuted fractures show a propensity to be slow to heal and increasing age and female gender further negatively impact on fracture healing. It has been shown that 2 cm of shortening of the clavicle Femoral shaft fractures It is possible to treat diaphyseal fractures of the femoral shaft non-operatively. The fracture can be reduced and held in position until union with traction; however, it takes 3 months. This is a long time to be in hospital and carries all the potential risks of prolonged bed rest. A tension band construct may be augmented by using circumferential wiring of the patella. Dynamic hip screw Tibial plateau fractures Intraarticular fractures of the tibial plateau are common. The articular surface once reduced is often held with plate and screw fixation or fine wire external fixation. This allows for compression at the fracture site on load-bearing and protects the femoral head from penetration by the screw when the osteoporotic bone settles; (b) insert to show the sliding screw in the barrel. Tibial shaft fractures For an undisplaced non-comminuted fracture of the tibial shaft, closed reduction and above knee cast is a safe and inexpensive treatment. Cast treatment requires close and constant monitoring of the position of the fracture site. A patient may choose to have an intramedullary nail to allow free knee and ankle movement. This is another situation where information and shared decision making can allow the patient to select the most appropriate treatment option. For comminuted and complex fractures of the tibial shaft, although cast treatment is possible, intramedullary nailing is preferred despite the potential complications of infection and anterior knee pain. Fractures at the diaphyseal metaphyseal junction at the knee and ankle are difficult to hold with an intramedullary nail and as such may be held with a plate and screws. Tibial fractures are also very amenable to external fixation with either a monolateral frame or fine wire circular construct, particularly where surgical skills and implants are not available for intramedullary nailing. With modern locked intramedullary implants, the patient will be up and out bed the following day and, if it is an isolated injury, home within a few days. If there is a simple fracture pattern with cortical apposition, it will be possible to mobilise with crutches, weight bearing as comfort allows. Although it may still take 3 months or more for the fracture to unite, the implant will be able to carry the load until union, allowing earlier return to function out of the hospital.

Buy genuine confido online

Other common audiological tests include speech audiometry mens health 2012 grooming awards confido 60 caps with visa, tympanometry, stapedial reflexes, electric response audiometry, otoacoustic emissions, caloric testing and electronystagmography (see Further reading). The patient sits in a soundproof room and the audiologist presents sounds at different thresholds and records the responses. An individual can have a congenital abnormality of the pinna and middle ear with a normal cochlea and therefore the potential for normal hearing. Trauma A haematoma of the pinna occurs when blood collects under the perichondrium. The cartilage receives its blood supply from the perichondrial layer and will die if the haematoma is not evacuated, resulting in a so-called cauliflower ear. The air-filled middle ear and the incus and stapes and the lateral and semicircular canals and internal acoustic meatus can be seen. In the right ear the entire middle ear and mastoid is opaque and filled with soft tissue. General anaesthesia may be required in children and those with learning difficulties. The cause is often cotton bud use, moist enviroment, immunocompromise, allergies or skin disorders, such as psoriasis and eczema. Common pathogens are Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus bacteria, Candida and Aspergillus. Once the skin of the ear canal becomes oedematous, skin migration stops and debris collects in the ear canal. The initial treatment is with a topical antibiotic and steroid ear drops together with analgesia. If this fails, meticulous removal of the debris with the aid of an operating microscope is required. The treatment is meticulous removal of the fungus and any debris, as well as stopping any concurrent antibiotics. Both may present as ulcerating or crusting lesions that grow slowly and may be ignored by elderly patients. All resectable malignant tumours of the ear are treated primarily with surgery, with or without the addition of radiation therapy. Trauma can also result in ossicular discontinuity and it is usually the incus that is displaced. Damaged ossicular chain and tympanic membrane are repaired by ossiculoplasty or tympanoplasty, respectively. Intensive systemic antibiotics are required and the disease process should be monitored by high-resolution imaging. The most common infecting organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. The most common complication is mastoiditis because the mastoid air cells connect freely with the middle ear space. If complications arise or the infection does not resolve quickly, a cortical mastoidectomy is required, which decompresses the mastoid cavity, together with a myringotomy and grommet insertion to ventilate the middle ear space. It has a bimodal incidence affecting 40% of 2 year olds and 20% of 5 year olds mainly in the winter months, suggesting an infective aetiology. Infection and inflammation of the immature Eustachian tube results in poor middle ear ventilation, negative pressure and the transudation of fluid. The following symptoms may be associated with glue ear: hearing impairment, which often fluctuates; delayed speech; behavioural problems; recurrent ear infections (the exudate is an ideal culture medium for microorganisms); reading and learning difficulties at school. A middle ear effusion in adults is often associated with an upper respiratory tract infection. A persistent unilateral effusion in an adult requires examination of the postnasal space to exclude obstructive nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which is the most common carcinoma in men in southern China. The cholesteatoma matrix destroys the structures in its path through the release of lytic enzymes, inflammatory mediators and pressure necrosis. The recommended treatment is mastoid surgery using a drill under microscopic or endoscopic guidence to access and remove the cholesteatoma. Often the ossicles are involved or eroded so an ossiculoplasty (to restore hearing by reconstructing the ossicular chain) is performed at the same time. A diagnosis should be suspected in any patient with a conductive hearing loss and a normal tympanic membrane. In the temporal bone, three types of glomus tumour are recognised and classification depends on the location: glomus tympanicum (arising in the middle ear), glomus jugularae (arising next to the jugular bulb) and glomus vagale (skull base). Symptoms include pulse synchronous tinnitus, conductive and sensorineural hearing loss, and lower cranial nerve palsies. The treatment of choice is preoperative embolisation followed by surgical excision. Squamous carcinomas usually arise in a chronically discharging ear and can arise in a chronically infected mastoid cavity. Radical surgical excision with or without radiotherapy provides the only chance of cure. Of the genetic hearing loss 75% is non-syndromic, of which the most common is a connexin 26 gene mutation. Syndromic causes include Usher, Pendred, Jervell and Lange-Nielsen, Waardenberg, Treacher Collins, Alport, Stickler neurofibromatosis type 2 and branchio-oto-renal syndromes. If some hearing is present, the early fitment of hearing aids can maximise the neural plasticity that is present in the developing brain. Most cases of profound sensorineural hearing loss are due to loss of cochlear hair cells, so an implant inserted through the round window can selectively stimulate the cochlear neurones, which usually remain intact. Presbycusis Presbycusis is characterised by a gradual loss of hearing in both ears, with or without tinnitus. The consonants of speech lie within the high-frequency range, which makes speech discrimination difficult. Many patients with presbycusis are concerned that they may lose their hearing completely and they need reassurance. Tinnitus Tinnitus is the perception of sound when no external sound source is present. It may have an extrinsic cause; for example, the pulsatile tinnitus of a glomus tumour. Tinnitus frequently accompanies presbycusis, as well as any other condition that affects hearing. Most individuals habituate to the presence of tinnitus but in some patients it proves intrusive. Treatment is with reassurance, masking and hearing aids (for patients with hearing loss). Sudden sensorineural hearing loss Defined as >30 dB sensorineural hearing loss at 3 frequencies within 3 days. History and examination should focus on a cause, which may be infective, neoplastic, traumatic, ototoxic, neurological or autoimmune. Sixty per cent are idiopathic and the recommended treatment is oral +/- intratympanic steroids with salvage intratympanic steroids for those that do not recover after a month. These are traditionally described as either longitudinal (80%) or transverse (20%); however, the majority have longitudinal and transverse components. Vestibular neuronitis Infection or inflamation of the supererior vestibular nerve, often caused by a upper respiratory or chest infection, results in persistent vertigo lasting a few days. Treatment is supportive with vestibular sedatives such as prochlorperazine in the first week followed by early mobilisation. Drug ototoxicity Antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, vancomycin and erythromycin, loop diuretics such as frusemide, chemotherapy agents such as cisplatin and carboplatin, and salicylates such as aspirin and quinine are all ototoxic. Recognition of risk factors, such as poor renal function in patients being treated with aminoglycosides, is therefore important. There is certainly evidence of endolymphatic hydrops (long-standing high pressure changes within the inner ear) in pathological specimens of patients who have had the condition.

Confido 60 caps free shipping

While postoperative review by the surgical team is encouraged mens health blog 60 caps confido overnight delivery, the discharge should not be delayed by failure of their timely attendance. It implies that a physical force exerted on a person has led to a physical injury. External energy forms and forces that can lead to injury include chemical, thermal, ionising radiation and, most frequently, those of mechanical origin. The degree and severity of trauma sustained can vary substantially and depend upon the magnitude of force exerted. In the next group of chapters, trauma will be examined from a variety of viewpoints, interconnected to different specialties. It is notable that the major burden of injury is increasingly occurring in middle- and low-income countries as they industrialise and adopt motorised transportation. In terms of the annual incidence and trends over time there is variation from country to country. Information is usually obtained from national statistics organisations that use the International Classification of Disease, a system that can be limited in providing accurate descriptions of injury severity. Of these, 21 657 people were seriously injured, among whom 1730 lost their lives, representing a 3% decrease compared with 2014. Of the 32 countries covered, 21 had an increase in the number of fatalities in 2015, ten had a decrease, and one remained unchanged. The only European countries with a better rate than this in 2015 were Sweden with 26. A large proportion of the severely injured survivors experience long-term or permanent disability as a result of their injuries. Almost 30% of them are no longer able to return to their previous occupation and a great deal of time is lost from work. These individuals end up having profound changes in their lifestyle, with long-term pain and suffering. Countries marked with a red outline have fewer than 150 deaths per year and therefore the fatality rate can vary signi cantly between years. Moreover, additional costs, due to loss of earnings, loss of productivity and quality of life damage, increase the total sum significantly. While young patients are involved in road traffic accidents characterised by high energy transfer, older patients may sustain injuries from falls (low energy transfer). Approximately 65 000 to 70 000 patients are admitted annually with proximal femoral fractures, among whom 30% over the age of 65 will die within a year of the incident. Most of the rest will end up having diminished independence and functional capacity. It is therefore no surprise that this particular cohort of patients, which will increase in the coming years owing to the anticipated increase in life expectancy, is thought to represent a huge burden on healthcare services and society in general. In general terms, the vast majority of injuries sustained are not limb threatening or life threatening. They are straightforward and most patients are expected to recover fully and return to their preinjury status. Nonetheless, the challenge remains to appreciate and diagnose the injuries at an early stage, with an awareness of important features that may influence the outcome. Of note, it has been shown that in 66% of cases when children die as a result of abuse, there has been some previous interaction with a health professional or social services but the seriousness of the situation was not fully appreciated. Our initial assessment and concepts of management have specific objectives and are usually based on knowledge acquired over a long period of time in practice. A better understanding of the physiological processes underpinning the host responses to an acute threat to our homeostatic mechanisms, together with protocols formulated to allow clinicians to use standardised measures and to speak a common language, have revolutionised the way we manage patients. All of the above help to reduce delays, particularly when under pressure to make a decision. However, it remains crucial to understand the reasoning as to why we are carrying them out. In trauma, as in other acute conditions, the patient is particularly reliant upon the clinician. A patient with a chronic condition is familiar with the nature of their problem and the way in which it is progressing. The surgeon may offer a remedy and the patient may consider the potential benefits and choose appropriately whether to accept it. The injured patient does not know what will happen without treatment and so relies on their surgeon to inform them of both the natural history and the potential benefits of any intervention. In the seconds prior to the application of the external injury force or vector, the patient is at their normal baseline, which can be called time zero. Moreover, the timeline allows evaluation of any progress made from time zero to other important events and to reflect on whether a specific course of action could have been performed better. Overall, interventions can be distinguished as emergency (life saving), acute (restoring haemodynamic stability) and delayed or semielective, focusing on the treatment of postfracture fixation complications (non-union, infection and malunion from the orthopaedic trauma point of view). It is essential to appreciate that the physiological crisis initiated in the immediate aftermath of trauma will continue to evolve and the risk of mortality is substantial unless the correct and timely interventions are performed. For instance, conditions such as airway obstruction, tension haemothorax and haemopericardium can progress very rapidly if left untreated and should be given priority in terms of our initial medical response to the injured patient. Thus, the seriousness and the immediate impact of a specific clinical condition should be prioritised and treated in a systematic approach (what kills first should be managed first). Evaluating and diagnosing a condition can be challenging, as the initial clinical signs may be non-specific. The clinical condition will continue to evolve as the time progresses, but by the time the diagnosis has been made it may be too late to prevent mortality. Surgical decompression can be organised speedily, reducing the risk of morbidity and mortality. Reducing the diagnosis time and response time of our interventions is dependent not only on the clinical staff but also on the availability of resources. Recently, the 24/7 availability of the trauma team and the designation of regional hospitals to operate as Level I Trauma Centres, with the availability of all disciplines and appropriate equipment on site, has provided the necessary foundation for the development of a unified trauma care system in England. Indeed, the first reports published on its effectiveness in saving lives have been very positive. Such a strategy may reduce the risk of having undiagnosed injuries and delays in their treatment. A number of studies have been published reporting on missed injuries and making some recommendations on how to avoid this. The timeline following an injury is continuous, and the accumulated documentation may become voluminous, complex and confusing. It is helpful periodically to make the effort to stand back and summarise the situation. The associations among these three factors are usually very clear, but can be hidden. For instance, a 50-year-old male restrained passenger in a car involved in a head-on collision with another vehicle may sustain rib fractures, a sternal fracture, thoracic spine fracture and possibly cardiac contusion. Abdominal injuries could also be suspected but, overall, the clinician, knowing the mechanism, can proceed quickly in making the diagnosis and initiating treatment. We will now analyse how the clinician can make best use of the information available. It can be seen that relying on obvious clinical signs gives insufficient time to respond effectively. The key issue, irrespective of the type of patient managed, with or without multiple injuries, is to reduce unnecessary delays in making the diagnosis and initiating appropriate treatment. Such a global approach would save lives, minimise morbidity and would make the healthcare system more efficient in terms of resource utilisation, as well as cost-effectiveness. Finally, it should not be forgotten that all clinical conditions are characterised by a dynamic process. This implies that our observations and analysis of the situation can change rapidly and to an extent that interventions would have to be modified accordingly. Ongoing evaluation of the patient is therefore essential in order to identify and respond to the changes noted in a timely fashion (as previously discussed).

Cheap 60caps confido fast delivery

Penetrating thoracic wounds vary according to the prevalence of civil violence androgen vs hormone generic confido 60 caps mastercard, with a mortality rate of 3% for simple stabbing to 15% for gunshot wounds. The indications for emergency room thoracotomy are similar to those for blunt chest trauma. The standard approach is a left anterior thoracotomy, unless the penetrating injury is in the right chest, however it may be necessary to extend the incision to bilateral thoracotomies or a clampshell incision. Early deaths after thoracic trauma are caused by hypoxaemia, hypovolaemia and tamponade. The first steps in treating such patients should be to diagnose and treat these problems as early as possible because they may be readily corrected. Young patients have a large physiological reserve, and serious injury may be overlooked until this reserve is used up, by which time the situation is critical and may be irretrievable. The best approach is to remain highly suspicious if lifethreatening conditions are to be anticipated and treated. The usual sites of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: 1, foramen of Morgagni; 2, oesophageal hiatus; 3, foramen of Bochdalek (pleuroperitoneal hernia); 4, dome. The foramen of Morgagni: a hernia in the anterior part of the diaphragm with a defect between the sternal and costal attachments. Unless there is severe bleeding or strangulation of the viscera it is best managed after an interval. In a severely injured patient being ventilated it can wait until other injuries are dealt with and weaning from the ventilator is being considered. When the diaphragm is breached, as in anatomical disorders, repair with either primary closure or with a mesh is usually possible via a thoracotomy. Diaphragmatic paralysis, particularly idiopathic unilateral paralysis, can be treated by plication, returning the diaphragm to a lower position and improving thoracic volume. They are treated similarly to those that occur at other sites and require specialist surgical input only if major resection and chest wall reconstruction are contemplated. The left pleural cavity is occupied by intestine, the mediastinum is displaced to the right and the right lung is aerated very little. The lower trunk of the plexus (mainly T1) is compressed, leading to wasting of the interossei and altered sensation in the T1 distribution. Compression of the subclavian artery may result in a poststenotic dilatation with thrombus and embolus formation. Therefore, the two main aims when treating claudication are prevention of major cardiovascular morbidity through risk factor modification and symptom relief/improvement. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk and severity of claudication proportional to the duration of affliction. Strict control in combination with weight loss in the obese patient is vital to reduce cardiovascular risk and prevent symptom deterioration. Other agents, such as vasodilators, are unlikely to provide either significant or sustained benefit. Following percutaneous femoral artery puncture under local anaesthetic, a guidewire is inserted and negotiated through the stenosis or occlusion under fluoroscopic control. A balloon catheter is then inserted over the guidewire and positioned within the lesion. The balloon is then inflated at high pressure for approximately 30 seconds and deflated. Long occlusions may be treated by the technique of subintimal angioplasty, where the guidewire crosses the lesion in the subintimal space (in the arterial wall) and a new lumen is created by inflation of the balloon. This may be introduced on a balloon catheter and expanded by balloon inflation; or alternatively, a self-expanding stent may be used that is contained inside a plastic sheath and deployed by withdrawal of the sheath. The advantage of this technique is that it can be carried out under local anaesthesia using the Seldinger technique of percutaneous arterial puncture, and is therefore especially useful in the treatment of patients who are medically unfit for major surgery. The stenosis was probably due to fibromuscular hyperplasia, but no tissue was available for histological diagnosis. Operations for arterial stenosis or occlusion Site of disease and type of operation Surgical operations are usually reserved for patients with severe symptoms where angioplasty has failed or is not possible. In unfit patients, an axillofemoral bypass is an alternative, although patency rates are less. If only one iliac system is occluded, an iliofemoral or femorofemoral crossover graft may be performed. Isolated common femoral artery or profunda disease can be treated with endarterectomy and patch (vein or prosthetic) or a short bypass in the groin. Sometimes, in patients with critical leg ischaemia, the occlusion extends beyond the popliteal artery into the tibial vessels. Limb salvage can be attempted with a femorodistal bypass, with success even more dependent on the state of the run-off vessel and the quality of the vein conduit (minimum diameter 3 mm). The risk of early graft failure with limb loss is high and these long bypasses are only appropriate for limb salvage. Technical details For aortofemoral bypass, the aorta should be approached through a midline abdominal incision; a transverse abdominal incision divides the inferior epigastric vessels (important collateral vessel in patients with an occluded aorta) and should be avoided. The common femoral arteries and their branches are exposed through vertical groin incisions. A vertical incision is made in the anterior aspect of the aorta to which an obliquely cut, bifurcated Dacron graft is sutured end-to-side with a nonabsorbable suture (polypropylene). The graft limbs are then fed down to the groins where they are anastomosed end-toside to the common femoral arteries or, if there is evidence of profunda stenosis, to an arteriotomy running from the common femoral vessel down into the profunda. For femoropopliteal bypass the popliteal artery above or below the knee is exposed through a medial incision. First, it may be excised, its tributaries tied, and the vein used in a reversed fashion so the valves do not obstruct the flow of blood. Alternatively, it may be left in place (in situ) and the valves disrupted with a valvulotome. The graft is sutured to the femoral artery proximally and to the popliteal artery distally. Femorodistal bypass involves fashioning the distal anastomosis to a tibial vessel. A femorofemoral crossover graft involves tunnelling a prosthetic graft subcutaneously above the pubis between the groins. An axillofemoral graft is tunnelled subcutaneously between the axillary artery proximally, to reach one or both femoral arteries; the patency rate of an axillobifemoral bypass is better than that of an axillo(uni)femoral bypass. Other sites of atheromatous occlusive disease the principles of arterial surgery outlined above can be applied at other arterial sites. These short-lived mini-strokes are often recurrent and cause unilateral motor or sensory loss in the arm, leg or face, transient blindness (amaurosis fugax) or speech impairment. They are caused by distal embolisation of platelet thrombi that form on the atheromatous plaque into the cerebral circulation. This involves clamping the vessels, an arteriotomy in the common carotid artery continued up into the internal carotid artery through the diseased segment, removal of the occlusive disease (endarterectomy) and closure of the arteriotomy, often with a patch. Many surgeons also use a temporary shunt to maintain cerebral blood flow while the carotid system is clamped. Results of operation Long-term results of aortoiliac reconstructive surgery are good, usually marred only by progressive infrainguinal disease. Immediate postoperative success for vein bypass exceeds 90% but the 5-year patency is around 60%. Although the results of femorodistal bypass are even less satisfactory, such surgery can ensure limb salvage in patients who are generally debilitated and whose expected lifespan is limited; long-term patency is less important. It usually affects the most distal part of a limb because of arterial obstruction (from thrombosis, embolus or arteritis). Dry gangrene occurs when the tissues are desiccated by gradual slowing of the bloodstream; it is typically the result of atheromatous occlusion of arteries. Crepitus may be palpated as a result of infection by gas-forming organisms, commonly in diabetic foot problems, and should be considered a surgical emergency with urgent tissue debridement or amputation required.

Buy cheap confido 60caps line

Paralysis mens health 6 pack challenge diet buy confido 60 caps low price, paraesthesia and pallor are late signs and pulselessness is an extremely late sign. Compartment pressure monitoring may be useful in cases of diagnostic uncertainty and in patients with altered levels of consciousness (intubated, head injury). Measure multiple sites near but not in the fracture site, in all the compartments of the affected limb. Emergency treatment involves splitting casts and or dressings to the skin and elevating the extremity. Senior input should be sought and arrangements put in place to perform definitive treatment with fasciotomies. The incidence of compartment syndrome associated with high and low energy injuries is nearly equal. The depletion of the ozone layer and global warming mean that the future may hold in store calamitous events with even greater magnitude than those experienced before. Nevertheless, there are numerous common elements and it has been shown that countries that invest in disaster preparedness are better equipped to cope with such catastrophes. Recent wars and disasters have highlighted the increasingly crucial role of surgeons in these scenarios. Conversely, natural disasters, such as earthquakes and tsunamis, leave in their wake massive destruction over large areas that can transcend national boundaries. Large numbers of people may require immediate shelter, clean water and food, in addition to any medical needs. A breakdown of communication is inevitable and can be accompanied by widespread panic and a disruption of civil order. Access to the disaster area may be limited because of the destruction of bridges, affecting road and rail links. Earthquakes can unleash havoc in seconds but floods and hurricanes may continue for several days. Another important factor is the state of resources of the country; disasters in poorer countries can seldom be managed without significant outside assistance. Nonetheless, there is an inevitable lag period between the occurrence of the disaster and the response from the establishment. However, these areas are densely populated and may have limited access by road and air. Disasters in remote areas can be particularly difficult to manage because relief efforts are hampered by geographical isolation and the lack of infrastructure. Damage assessment the first objective in disaster management is an assessment of the damage and the number of casualties. Mobilising resources the next step is mobilisation of human and material resources appropriate to the extent of the disaster. The teams who make up the initial response must include experienced staff who can assess the situation and who have the authority to take immediate decisions. Coordinating the efforts of these organisations is essential for optimal results, as medical aid in isolation is inadequate without the simultaneous provision of safe drinking water, food, clothing and shelter. Rescue operation Early coordination of the rescue effort allows optimal use of resources. The first priority is to prevent further damage from occurring, both to people and to the infrastructure. Triage should be undertaken by someone senior, who has the experience and authority to make these critical decisions. To keep pace with the changing clinical picture of an injured person, triage needs to be undertaken in the field, before evacuation and at the hospital. Triage areas For efficient triage the injured need to be brought together into any undamaged structures that can shelter a large number of wounded. Separate areas should be reserved for patient holding, emergency treatment and decontamination (in the event of discharge of hazardous materials). Practical triage Emergency life-saving measures should proceed alongside triage and can actually help the decision-making process. The assessment and restoration of airway, breathing and circulation are critical and are discussed in Chapter 23. Vital signs and a general physical examination should be combined with a brief history taken by a paramedic or by a volunteer worker if one is available. It is essential to establish a working relationship between the media and the rescue teams. With careful handling the media can become a powerful ally and play a constructive role in identifying problems, galvanising aid and keeping the public informed. Documentation for triage Accurate documentation is an inseparable part of triage and should include basic patient data, vital signs with timing, brief details of injuries (preferably on a diagram) and treatment given. By sorting out the minor injuries, triage lessens the immediate burden on medical facilities. Priority First (I) Colour Red Medical need Immediate Clinical status Triage categories All methods of triage use simple criteria based on vital signs. This is done on the basis of need so that resources can be allocated by good prioritisation. An adequate supply of essentials such as intravenous fluids, dressings, pain medication, and oxygen must be arranged (see Chapter 30). Whether the traditional tented structure or the modular type housed in containers is employed, the facility must be equipped with radiograph capability, operating rooms, vital signs monitors, sterilising equipment, a blood bank, ventilators and basic laboratory facilities. Management in the field Field hospitals principally function in three main areas (Table 29. Field hospitals the decision to deploy field hospitals depends on the location, the number of casualties and the speed with which Summary box 29. This will include ensuring that the airway is secure, haemorrhage is under control and compartments are decompressed in the chest, skull, abdomen and the limbs. Examples First aid Emergency care for lifethreatening injuries Suturing cuts and lacerations, splinting simple fractures Endotracheal intubation, tracheotomy, relieving tension pneumothorax, stopping external haemorrhage, relieving an extradural haematoma, emergency thoracotomy/laparotomy for internal haemorrhage Debridement of contaminated wounds, reduction of fractures and dislocations, application of external fixators, vascular repairs Further Review at local hospital After damage control surgery, transfer patients to base hospitals once stable Initial care for non-lifethreatening injuries Transfer patients to base hospitals for definitive management developing into infection. A needle thoracocentesis will relieve a tension pneumothorax and a chest drain will be needed before a patient with a significant chest injury is transferred by air. Amputation for clearly devitalised limbs and gas gangrene should be undertaken at field hospitals as delay will be fatal. Specific aspects of care are discussed in the relevant chapters elsewhere in this book. Initial care for non-life-threatening injuries Many patients sustain serious injuries that require prolonged care. These include compound limb fractures, degloving injuries, dislocations of major joints, major facial injuries and complex hand injuries. These patients will need specialised care requiring transfer to the appropriate facility. Replantations of amputated limbs and other extensive procedures should not be attempted in field hospitals as they are time-consuming and divert resources and personnel to the treatment of a few patients. Debridement reduces the chances of anaerobic and necrotising infections and can prevent systemic sepsis. The following principles of debridement apply to all contaminated wounds: (a) After the administration of anaesthesia, the injured area is copiously irrigated with normal saline. Dirt and debris enmeshed in soft tissues can only be removed by excision of those tissues. Wounds with extensive cavitation should be enlarged longitudinally to gain better access and allow full decompression of the underlying muscles. This helps to visualise the damaged structures, and allow the surgeon to gain proximal and distal control of vascular injuries, and to identify severed ends of major nerves and tendons. Skin excision is kept to a minimum and only the margins of the wound need be trimmed back to healthy bleeding edges.

Buy confido with american express

Mastitis of infants Mastitis of infants is at least as common in boys as in girls man health pay bill pay bill purchase confido 60caps fast delivery. On the third or fourth day of life, if the breast of an infant is pressed lightly, a drop of colourless fluid can be expressed; a few days later, there is often a slight milky secretion, which disappears during the third week. It is caused by stimulation of the fetal breast by prolactin in response to the drop in maternal oestrogens and is essentially physiological. Diffuse hypertrophy Diffuse hypertrophy of the breasts occurs sporadically in otherwise healthy girls at puberty (benign virginal hypertrophy) and, much less often, during the first pregnancy. This tremendous overgrowth is apparently caused by an alteration in the normal sensitivity of the breast to oestrogenic hormones and some success in treating it with antioestrogens has been reported. Traumatic fat necrosis Traumatic fat necrosis may be acute or chronic and usually occurs in stout, middle-aged women. This may mimic a carcinoma, even displaying skin tethering and nipple retraction, and biopsy is required for diagnosis. A seatbelt may transect or avulse the breast with a sudden deceleration injury, as in a road traffic accident. This advice has been replaced with the recommendation that repeated aspirations under antibiotic cover (if necessary using ultrasound for localisation) be performed. This often allows resolution without the need for an incision and will also allow the patient to continue breast-feeding. The presence of pus can be confirmed with needle aspiration, and the pus should be sent for bacteriological culture. When in doubt, an ultrasound scan may clearly define an area suitable for drainage. Acute and subacute inflammations of the breast Bacterial mastitis Bacterial mastitis is the most common variety of mastitis and is associated with lactation in the majority of cases. The intermediary is usually the infant; after the second day of life, 50% of infants harbour staphylococci in the nasopharynx. Although ascending infection from a sore and cracked nipple may initiate the mastitis, in many cases the lactiferous ducts will first become blocked by epithelial debris leading to stasis; this theory is supported by the relatively high incidence of mastitis in women with a retracted nipple. Once within the ampulla of the duct, staphylococci cause clotting of milk and, within this clot, organisms multiply. This is a large, sterile, brawny oedematous swelling that takes many weeks to resolve. It used to be recommended that the breast should be incised and drained if the infection did not resolve within 48 hours or if after being emptied of milk there was an area of tense induration or other evidence of an underlying abscess. Operative drainage of a breast abscess this is less commonly needed as prompt commencement of antibiotics and repeated aspiration is usually successful. The usual incision is sited in a radial direction over the affected segment, although if a circumareolar incision will allow adequate access to the affected area this is preferred because it gives a better cosmetic result. Every part of the abscess is palpated against the point of the artery forceps and its jaws are opened. Finally, the artery forceps having been withdrawn, a finger is introduced and any remaining septa are disrupted. The wound may then be lightly packed with ribbon gauze or a drain inserted to allow dependent drainage. Chronic intramammary abscess A chronic intramammary abscess, which may follow inadequate drainage or injudicious antibiotic treatment, is often a very difficult condition to diagnose. When encapsulated within a thick wall of fibrous tissue the condition cannot be distinguished from a carcinoma without the histological evidence from a biopsy. Tuberculosis of the breast Tuberculosis of the breast, which is comparatively rare, is usually associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis or tuberculous cervical adenitis. Tuberculosis of the breast occurs more often in parous women and usually presents with multiple chronic abscesses and sinuses and a typical bluish, attenuated appearance of the surrounding skin. Healing is usual, although often delayed, and mastectomy should be restricted to patients with persistent residual infection. In the absence of injury or infection, the cause of thrombophlebitis (like that of spontaneous thrombophlebitis in other sites) is obscure. The pathognomonic feature is a thrombosed subcutaneous cord, usually attached to the skin. The differential diagnosis is lymphatic permeation from an occult carcinoma of the breast. The condition usually subsides within a few months without recurrence, complications or deformity. The classical description of the pathogenesis of duct ectasia asserts that the first stage in the disorder is a dilatation in one or more of the larger lactiferous ducts, which fill with a stagnant brown or green secretion. In some cases, a chronic indurated mass forms beneath the areola, which mimics a carcinoma. There is often little correlation between the histological appearance of the breast tissue and the symptoms. Nodularity Frequency An alternative theory suggests that periductal inflammation is the primary condition and, indeed, anaerobic bacterial infection is found in some cases. A marked association between recurrent periductal inflammation and smoking has been demonstrated. This was thought by some to indicate that arteriopathy is a contributing factor in its aetiology, although others believe that smoking increases the virulence of the commensal bacteria. It is certainly clear that cessation of smoking increases the chance of a long-term cure. Antibiotic therapy may be tried, the most appropriate agents being co-amoxiclav or flucloxacillin and metronidazole. It is particularly important to shave the back of the nipple to ensure that all terminal ducts are removed. Pathology the disease consists essentially of four features that may vary in extent and degree in any one breast. Fat and elastic tissues disappear and are replaced with dense white fibrous trabeculae. Hyperplasia of epithelium in the lining of the ducts and acini may occur, with or without atypia. The epithelial hyperplasia may be so extensive that it results in papillomatous overgrowth within the ducts. Aberrations of normal development and involution Nomenclature the nomenclature of benign breast disease is confusing. This is because over the last century a variety of clinicians and pathologists have chosen to describe a mixture of physiological changes and disease processes according to a variety of clinical, pathological and aetiological terminology. As well as leading to confusion, patients were often unduly alarmed or overtreated by ascribing a pathological name to a variant of physiological development. Lumpiness may be bilateral, commonly in the upper outer quadrant or, less commonly, confined to one quadrant of one breast. The changes may be cyclical, with an increase in both lumpiness and often tenderness before a menstrual period. It should be distinguished from referred pain, for example a musculoskeletal disorder. About 5% of breast cancers exhibit pain at presentation, but rarely as the sole presenting feature. It is perhaps worthwhile reviewing the patient at a different point in the menstrual cycle, for example 6 weeks after the initial visit as often the clinical signs will have resolved by that time. There is a tendency for women with lumpy breasts to be rendered unnecessarily anxious and to be submitted to multiple random biopsies because the clinician lacks the courage of his or her convictions. Rapid referral into the secondary health care sytem often means patients are assessed without an intervening menstrual cycle and this may lead to additional concerns. Initially, firm reassurance that the symptoms are not associated with cancer will help the majority of women. Acknowledgement that this is a real symptom, a non-dismissive attitude and an explanation of the aetiology are all helpful in managing this condition. In the first instance, an appropriately fitting and supportive bra should be worn throughout the day and a soft bra (such as a sports bra) worn at night.