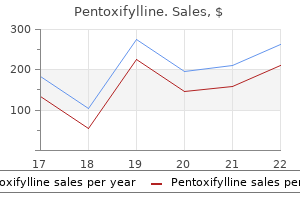

Order cheapest pentoxifylline

Microscopically rheumatoid arthritis weight gain buy pentoxifylline without prescription, the cells are typically very uniform with hyperchromatic nuclei that are slightly larger than normal lymphocytes. A moderate amount of palestaining or clear cytoplasm is present and this gives the cells a regularly spaced appearance. Scattered larger blastlike cells with more open nuclei and prominent nucleoli are present, but these cells are usually inconspicuous. Tumor stroma is typically lacking, but bands of hyaline connective tissue in these solid areas may represent residual lung structures and cytokeratin staining often reveals compressed cords of lung epithelium. Here the neoplastic cells follow lymphatic pathways to form dense interstitial infiltrates. Interlobular and alveolar septa widen and peribronchial, peribronchiolar and perivascular nodules are seen. Lymphoepithelial lesions are best seen in these areas, where bronchial or bronchiolar epithelium is infiltrated by small clusters of tumour cells. A follicular pattern is usually present in parts of the tumor and may even dominate the histology. Some of the apparent follicles consist entirely of tumor cells, with a uniform appearance, whereas others have a central zone consisting of normal follicle center cells, with a normal mix of small and large follicle center cells. Unlike a reactive lymphoid follicle, the boundary between the outer zone of neoplastic cells and the central group of follicle center cells is usually blurred. In most tumors this is not a prominent feature but it is occasionally more evident. Abundant immunoglobulin production may be associated with crystal-storing histiocytosis, in which large numbers of histiocytes contain crystalline immunoglobulin, usually of IgM kappa type. This process can be inferred if there is biopsy evidence of the sequence or if the two tumors are seen together in the same biopsy. This may be diffusely deposited in the stroma of the tumor or may form one or more nodules of amyloid. In follicular aggregates, T-cells tend to cluster in the residual germinal centers. The infiltrate follows lymphatic pathways in visceral pleura, interlobular septa and bronchovascular bundles. Some cells show plasmacytic differentiation and some have intranuclear inclusions, so called Dutcher bodies (arrows). Transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a mix of cells including large blasts and plasmacytic cells. Determination of malignancy, and the distinction from a reactive lymphoid infiltrate, may depend on the demonstration of light chain restriction in the tumor cells, the monotypic tumor cells contrasting with the polytypic population in residual benign follicles. Staining for heavy chains usually shows IgM production, and occasionally IgG or IgA. Proliferation markers, such as Ki67, show a uniformly low proliferation fraction, again in contrast to residual follicles, which may appear as clusters of cells in cycle. This is seen in patients without underlying autoimmune disease and correlates well with typical histology, lack of marked plasmacytic differentiation, and small numbers of large cells. The diagnosis is more easily established if the biopsies include airway epithelium with lymphoepithelial lesions. Frequently, the morphological features are considerably distorted and the dense infiltrate of crushed, hyperchromatic cells may easily be mistaken for small cell carcinoma. Other types of small B-cell lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma are rare as primary lung lesions and can usually be excluded by immunohistochemistry (Table 2). A needle-core biopsy showing a diffuse, dense lymphoid infiltrate with obliteration of normal lung structure. An intraoperative smear preparation showing uniform round nuclei with clumped chromatin and a zone of palestaining cytoplasm. It is very helpful in this situation to make imprint or smear preparations from the tumor in addition to the cryostat sections. This appearance is in contrast to small cell carcinoma, where the nuclei show a greater degree of pleomorphism and more dispersed granular chromatin, lack significant cytoplasm and tend to mold together. In smears from carcinoid tumors, the cells also tend to disperse but the nuclei have very uniform chromatin and are typically oval or commashaped. In frozen sections, a lymphomatous infiltrate can often be seen to be interstitial, and lymphoepithelial lesions may be apparent. The presence of lymphoid nodules or residual follicles may lead to a mistaken diagnosis of an inflammatory mass. An area of organizing pneumonia would not usually be mistaken for low-grade lymphoma, as the appearances are much more heterogeneous and areas of fibrosis are apparent. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, which has in the past been known by various terms including inflammatory pseudotumor and plasma cell granuloma, may contain large numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes, occasionally with reactive follicles (see Chapter 33). Treatment Treatment options include local resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and interferon-a. The 5-year survival rate is over 80% and 10-year survival rates range from 70% to 85%, despite recurrences in either the lung or other extranodal sites. The proliferation fraction, assessed by markers such as Ki67, is between 50% and 100%. The main differential diagnosis is from other undifferentiated tumors, particularly undifferentiated carcinoma of non-small cell type, or occasionally malignant Clinical features Excluding patients with known immunodeficiency, the age at presentation ranges from 30 to 80 years with a mean of about 60 years. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma must also be distinguished from other types of high-grade malignant lymphoma, such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma. High-grade extranodal lymphomas may carry other abnormalities, such as t(8;14)(q24;q32). Although an extremely rare finding, malignant follicles tracking through the lung in a lymphangitic pattern occurs. Primary lung involvement, with bilateral consolidation and no evidence of systemic disease elsewhere, is described. The patients typically showed nodular pulmonary infiltrates, often with central necrosis. Microscopically, these were associated with a polymorphous infiltrate, sometimes including atypical cells with a characteristic angiocentric pattern. As the name implies, the nature of the disease process was unclear and its course was very variable: in some patients it was very indolent, whereas in others it behaved as a high-grade malignant lymphoma. In a later expanded series of 152 patients, 12% had recognizable Other primary pulmonary B-cell lymphomas Primary involvement of the lung by other types of small B-cell lymphoma, without evidence of disease elsewhere, is rare. At present no specific markers are available for marginal zone cells and the antibodies shown in Table 2 should be used to exclude these other forms of lymphoma. This was in the belief that both conditions were post-thymic T-cell proliferations. In some patients with low-grade disease, probably corresponding to benign lymphocytic angiitis and granulomatosis, the process may completely resolve, suggesting a non-neoplastic etiology. The majority of patients are symptomatic, with respiratory symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, chest pain or hemoptysis; and systemic symptoms, such as pyrexia and weight loss. More rarely, the appearance mimics interstitial disease with ground-glass shadowing or reticulonodular opacities. Splenic and hepatic involvement is not apparent at presentation and lymphadenopathy is unusual. The lungs are involved in most cases, with skin involvement in 30:50% of patients and central or peripheral nervous system involvement in 10:30%. As the disease progresses there may be more widespread nodal or visceral involvement. They are mixed with variable numbers of plasma cells, histiocytes and, in some cases, scattered eosinophils. The neoplastic population of larger B-cells may be inconspicuous in routine sections, with vesicular nuclei resembling histiocytes, or there may be more abundant atypical blasts, with coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli. The characteristic vascular infiltration is best seen at the periphery of the dense nodular aggregates or in the surrounding, less severely involved lung, but vessels in the necrotic areas may be infiltrated or ringed by surviving atypical cells. These form a transmural infiltrate in the walls of both arteries and veins and typically separate the layers of the vessel walls. The intima is thickened with resulting narrowing of the lumen, but the overlying endothelium remains intact and thrombosis is unusual. Rarely, there may be an associated inflammatory vasculitis with granulomatous features.

Discount pentoxifylline american express

Progressive systemic sclerosis-polymyositis overlap syndrome with eosinophilic pleural effusion arthritis back chiropractic buy genuine pentoxifylline on-line. Pleural fluid glucose with special reference to its concentration in rheumatoid pleurisy with effusion. Pleuropulmonary manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical features of its subgroups. Clinical features and pleural fluid characteristics with special reference to pleural fluid antinuclear antibodies. Pleuro-pulmonary endometriosis and pulmonary ectopic deciduosis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 10 cases with emphasis on diagnostic pitfalls. Endometriosisrelated pneumothorax: clinicopathologic observations from a newly diagnosed case. Gorham-Stout syndrome in a male adolescent-case report and review of the literature. An unusual case of calcifying fibrous pseudotumour of the cervicothoracic junction. Calcifying fibrous pseudotumor versus inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a histological and immunohistochemical comparison. Immunohistochemical analysis of anaplastic lymphoma kinase expression in deep soft tissue calcifying fibrous pseudotumor: evidence of a late sclerosing stage of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor Translocation (2;3)(p21;p26) as the sole anomaly in a benign localized fibrous mesothelioma. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: report of a case with cytogenetic analysis. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura presenting dry cough induced by postural position. Immunohistochemical localization of endothelial cell markers in solitary fibrous tumor. Brief report: activity of imatinib in a patient with platelet-derivedgrowth-factor receptor positive malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura with associated hypoglycemia: Doege-Potter syndrome: a case report. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: computed tomography-pathological correlation and comparison with computed tomography of benign solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Localized fibrous tumours of the pleura: 15 new cases and review of the literature. Myxoid solitary fibrous tumor: a study of seven cases with emphasis on differential diagnosis. A cytologic-histologic study with clinical, radiologic, and immunohistochemical correlations. Cytokeratin-positive malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura: an unusual pitfall in the diagnosis of pleural spindle cell neoplasms. Epithelioid, cytokeratin expressing malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura. Ultrastructural spectrum of solitary fibrous tumor: a unique perivascular tumor with alternative lines of differentiation. Lines of cell differentiation in solitary fibrous tumor: an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of 10 cases. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: clinicopathological characteristics, immunohistochemical profiles, and surgical outcomes with long-term follow-up. D2: 40-positive solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: diagnostic pitfall of biopsy specimen. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the pleura mimicking a malignant solitary fibrous tumor and associated with dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the mediastinum: usefulness of cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses. Pleuropulmonary desmoid tumors: immunohistochemical comparison with solitary fibrous tumors and assessment of beta-catenin and cyclin D1 expression. Immunohistochemical comparison of gastrointestinal stromal tumor and solitary fibrous tumor. Sensory receptors in the visceral pleura: neurochemical coding and live staining in whole mounts. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: an analysis of 110 patients treated in a single institution. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: results of surgical treatment and long-term prognosis. Syndrome of pleural and retrosternal "bridging" fibrosis and retroperitoneal fibrosis in patients with asbestos exposure. The importance of lung function, nonmalignant diseases associated with asbestos, and symptoms as predictors of ischaemic heart disease in shipyard workers exposed to asbestos. Mortality among British asbestos workers undergoing regular medical examinations (1971: 2005). Radiographic abnormalities among Finnish construction, shipyard and asbestos industry workers. Modelling prevalence and incidence of fibrosis and pleural plaques in asbestos-exposed populations for screening and followup: a cross-sectional study. Environmental fiber-induced pleuro-pulmonary diseases in an Anatolian village: an epidemiologic study. Bilateral pleural plaques in Corsica: a marker of non-occupational asbestos exposure. Decreasing prevalence of pleural calcifications among Metsovites with nonoccupational asbestos exposure. Pleural plaques and exposure to mineral fibres in a male urban necropsy population. Occupational asbestos exposure and predictable asbestos-related diseases in India. Asbestos related diseases from environmental exposure to crocidolite in Da-yao, China. An investigation of crocidolite contamination and mesothelioma in a rural area of China. Hyaline and calcified pleural plaques as an index for exposure to asbestos: a study of radiological and pathological features of 100 cases with a consideration of epidemiology. Analysis of asbestos fibers in lung parenchyma, pleural plaques, and mesothelioma tissues of North American insulation workers. Pleural plaques in dentists from occupational asbestos exposure: a report of three cases. Human epidemiology: a review of fiber type and characteristics in the development of malignant and nonmalignant disease. Survey of the biological effects of refractory ceramic fibres: overload and its possible consequences. Health effects of refractory ceramic fibres: scientific issues and policy considerations. Abnormalities of pulmonary function and pleural disease among titanium metal production workers. Epidemiologic study of lung cancer mortality in workers exposed to titanium tetrachloride. Effect of smoking on attack rates of pulmonary and pleural lesions related to exposure to asbestos dust. The preformed stomas connecting the pleural cavity and the lymphatics of the pleura. Milky spots (taches laiteuses) as structures which trap asbestos in mesothelial layers and their significance in the pathogenesis of mesothelial neoplasia. The pathogenesis of pleural plaques and pulmonary asbestosis: possibilities and impossibilities. Translocation of mineral fibres through the respiratory system after injection into the pleural cavity of rats. Asbestos retention in human respiratory tissues: comparative measurements in lung parenchyma and in parietal pleura. Asbestos upregulates expression of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor on mesothelial cells. Glutathione Stransferase and N-acetyltransferase genotypes and asbestos-associated pulmonary disorders. Genetic susceptibility to malignant pleural mesothelioma and other asbestos-associated diseases. Asbestos, asbestosis, and lung cancer: a critical assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Asbestos content of lung tissue and carcinoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic correlation and mineral fiber analysis of 234 cases.

Purchase pentoxifylline 400mg otc

Leiomyosarcomatous differentiation has not been reported and liposarcomatous differentiation is very rare arthritis ginger buy pentoxifylline 400mg without a prescription. This M:F ratio was higher than in other published cases of mesothelioma with heterologous elements. Of the 27 mesotheliomas, 16 (59%) were sarcomatoid, 10 (37%) were biphasic and one was reported as epithelioid but this was a needle biopsy diagnosis. Osteosarcomatous elements account for most cases (40%), 19% showed areas of only rhabdomyosarcoma, 19% contained areas of chondrosarcoma and 22% exhibited osteochondromatous elements. The difficulty of differentiating osteoid from hyaline collagen was highlighted in the paper. The proportion of the rhabdoid cells seen in these cases constituted 15:75% of the individual tumors. Cytoplasmic staining in the rhabdoid cells was seen for pan-keratin in all 10 cases, for calretinin in 9/10 and for cytokeratin 5/6 in seven of nine. Only one case showed desmin positivity in sparse cells in the non-rhabdoid component of the tumor. Ultrastructurally there were paranuclear collections of intermediate filaments, but no evidence of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation was seen. The differential diagnosis includes primary and secondary pleural sarcomas, including osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas, as well as pleomorphic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) involving the pleura. Heterologous elements can be identified in pulmonary carcinosarcomas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Lack of labeling for cytokeratins in a spindle cell/sarcomatoid tumor does not exclude mesothelioma, irrespective of the heterologous elements. If the anatomical distribution conforms to a mesothelioma, a diagnosis of "heterologous mesothelioma" should be made in preference to a diagnosis of primary pleural osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma, regardless of cytokeratin positivity. This issue is discussed below in the differential diagnosis section, where the problem of cytokeratin-negative mesotheliomas as well as cytokeratin-positive sarcomas is presented. This tumor poses a difficult diagnostic problem, even for experienced pathologists serving on reference panels. The arrangement of the collagenous areas varies but often there are no sarcomatoid foci. Such tumors should be thoroughly sampled and, if only little tissue is provided, multiple levels cut to try and identify sarcomatoid foci. The most common pattern is a complex network and anastomosing bands, often of hyalinized collagen, with a prominent whorled, micronodular or storiform pattern. This is always bland without any associated inflammation and on H&E sections resembles fibrinoid necrosis. In the latter there is often chronic inflammation, and if it is recent there is zonation, i. Another guide is in fibrosing pleurisy, there is often a relatively clear-cut line between the fibrotic pleura and fat. There will be some bland fibrous tissue extending between fat, but on low power it is possible to see a plane of cleavage. On the other surface, it grows into the lung parenchyma, along interlobar and interlobular septa and may extend into alveoli, resembling organizing pneumonia. Fourteen out of 16 cases coming to post-mortem had metastases, the commonest site being the contralateral lung. There are relatively few other biphasic lesions in the pleura to consider in the differential diagnosis (see below). It may be difficult in some cases of epithelioid mesothelioma to decide whether the stroma is sarcomatoid or part of the stromal reaction to the tumor. Deciduoid mesothelioma with characteristic large cells with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm. Subsequently several publications have shown that some of these rare variants have prognostic significance. Deciduoid peritoneal mesothelioma It was initially suggested that deciduoid mesothelioma was a distinct subtype with specific clinical and pathological features. Later reports showed this subtype may occur in elderly people in all three main serous cavities. Cases with this pattern as a single cell type are rare but deciduoid cells admixed with a tubulopapillary pattern are increasingly recognized. In 75 female peritoneal mesotheliomas, only two purely deciduoid cases were present. They are large, round, ovoid and polygonal with sharp cell outlines, abundant, glassy, eosinophilic cytoplasm and round vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Microcystic mesothelioma (adenomatoid) this tumor may affect the pleura and peritoneum, though is uncommon in the former site. The tumors are continuous with the parietal pleura and adherent to the visceral pleura. Small buds or clumps of mesothelial cells are sometimes seen within the cystic spaces. Some of the stromal cells between the cysts had features suggestive of a smooth muscle origin. It is essential to separate this entity from well differentiated papillary mesothelioma (see below). The tumor is characterized morphologically and ultrastructurally by numerous intracytoplasmic lipid vacuoles and numerous long branching and intertwining microvilli, characteristic but not diagnostic of epithelioid mesothelioma. Clear cell mesothelioma this variant may be confused with other metastatic clear cell tumors, especially renal and pulmonary clear cell carcinomas. Electron microscopy and special stains showed that the cytoplasmic clearing seen on H&E resulted from multiple factors, either singly or in combination. The most frequent cause was accumulation of large amounts of intracytoplasmic glycogen. Tumor giant cells are seen as well as an abnormal mitosis; (b) calretinin stain on this tumor (see text). Other rarer causes were marked mitochondrial swelling, the presence of numerous intracytoplasmic vesicles, and a large number of intracytoplasmic lumina. The nuclei were eccentric, round to oval, uniform and contained indistinct nucleoli. The cytoplasm had large numbers of round vesicles, bounded by a single membrane, which varied in size. Many vesicles were empty, others contained one or more smaller vesicles or an aggregate of electron-dense material. Clear cell carcinoma metastases to the pleura have been the most frequent cases for diagnostic confirmation in the French Mesothelioma Panel (2008; recent unpublished data). A rare clear cell sarcoma presenting in the pleura can cause diagnostic difficulties. Pleomorphic (giant cell) mesothelioma A rare variant of mesothelioma is the pleomorphic or giant cell type. This tumor may be confused with the giant cell or pleomorphic carcinoma of lung or a sarcoma, primary or secondary (see below for pleural sarcomas). If carcinoma is considered, mucin and neuroendocrine stains should be done to exclude an adeno- or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Large cell carcinoma, pleomorphic carcinoma, including the giant cell subtype, and small cell carcinoma can show nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity with calretinin. Some features may be useful in diagnosing poorly differentiated epithelioid mesotheliomas. These include a mosaic pattern of closely associated tumor cells with a few long, narrow cytoplasmic processes, lying parallel to adjacent plasma membranes. There is abundant cytoplasm with limited organelles, usually with a polar arrangement. The nuclei have a markedly disaggregated chromatin and prominent nucleolonemal-type nuclei. Small cell mesothelioma with no nuclear molding or other features of small cell carcinoma. This included reactivity of both epithelioid and/or spindle cell components in biphasic tumors.

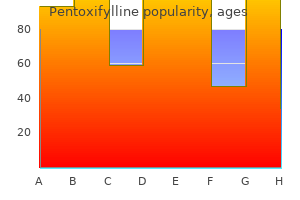

| Comparative prices of Pentoxifylline | ||

| # | Retailer | Average price |

| 1 | Menard | 269 |

| 2 | Dillard's | 712 |

| 3 | PetSmart | 838 |

| 4 | Sports Authority | 705 |

| 5 | Abercrombie & Fitch | 120 |

| 6 | Family Dollar | 518 |

| 7 | ShopRite | 760 |

| 8 | Sherwin-Williams | 916 |

| 9 | Starbucks | 911 |

Buy 400 mg pentoxifylline free shipping

Case Presentation You and your partner are transporting a seriously injured bicyclist arthritis medication that causes weight loss discount 400mg pentoxifylline with amex, who crashed into a parked vehicle, to a trauma capable hospital. The temporal bone (temple) is quite thin and easily fractured, as are portions of the base of the skull. The fibrous coverings of the brain are inside the skull and include the dura mater ("tough mother"), which covers the entire brain; the thinner pia arachnoid (called simply the arachnoid), which lies underneath the dura and in which are suspended both arteries and veins; and the very thin pia mater ("soft mother"), which lies underneath the arachnoid and is adherent to the surface of the brain. Because the brain "floats" inside the cerebrospinal fluid and is anchored at its base, there is greater movement at the top of the brain than at the base. On impact, the brain is able to move within the skull and can strike bony prominences within the cranial cavity. This concept (the Monro-Kellie Doctrine) is of great importance in the pathophysiology of head trauma. Because of the fixed space within rigid skull, as the brain tissue swells, it takes up more volume of the skull. Cerebrospinal fluid (also called spinal fluid) is a nutrient fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord. Spinal fluid is continually created within the ventricles of the brain at a rate of 0. The arachnoid granulations protruding into the superior sagittal sinus are the major site of absorption of spinal fluid. Primary and Secondary Brain Injuries primary brain injury: the immediate damage to the brain tissue that is the direct result of an injury force. Primary brain injury is the immediate damage to the brain tissue that is the direct result of the injury force and is essentially fixed at the time of injury. Primary brain injury is better managed by prevention, using measures such as the use of occupant restraint systems in autos; the use of helmets in sports, work, and cycling; and firearms education. Most closed head primary injuries occur either as a result of external forces applied against the exterior of the skull or from movement of the brain inside the skull. In deceleration injuries, the head usually strikes an object such as the windshield of an automobile, which causes a sudden deceleration of the skull. The brain continues to move forward, impacting first against the skull in the original direction of motion ("third" collision of a motor-vehicle collision) and then rebounding to hit the opposite side of the inner surface of the skull (a "fourth" collision). Thus, injuries may occur to the brain in the area of original impact ("coup") or on the opposite side ("contracoup"). Secondary brain injury is the result of hypoxia and/or decreased perfusion of brain tissue. As a consequence of other injuries, hypoxia or hypotension may occur with either insult damaging to brain tissue. The increase in cerebral water (edema) does not occur immediately, but develops over hours. Early efforts to prevent the accumulation of edema and to maintain perfusion of the brain can be life saving. In the past, swelling was believed to be worsened if there was increased blood flow to the injured brain. This increased pressure would in turn decrease blood flow to the brain, adding insult to injury. Research has shown that hyperventilation actually has only a slight effect on brain swelling, but causes a significant decrease in cerebral perfusion from that same vasoconstriction, resulting in cerebral hypoxia. However, hypoxia and hypotension appear to eliminate any neuroprotective mechanism normally afforded by age. If the child with a serious brain injury is allowed to become hypoxic or hypotensive, the chance of recovery is even worse than an adult with the same injury. Intracranial Pressure Brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid, and blood reside within the skull and fibrous coverings of the brain. An increase in the volume of any one of those components must be at the expense of the other two because the adult skull (a rigid box) cannot expand. Although there is some displacement volume of cerebrospinal fluid and venous blood, it accounts for little space and cannot offset rapid brain swelling. The body senses the rise in systemic blood pressure, and this triggers a drop in the pulse rate as the body tries to lower the systemic blood pressure. Signs include dilatation of pupils, contralateral paralysis, elevated blood pressure, and bradycardia. As stated earlier, the injured brain loses the ability to autoregulate blood flow. In this situation perfusion of the brain is directly dependent on arterial blood pressure. Remember, hypotension and the associated poor perfusion is devastating to the injured brain. This leads to obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid and applies significant pressure to the brainstem, resulting in cerebral herniation syndrome. In this situation the danger of immediate herniation outweighs the risk of cerebral ischemia that can follow hyperventilation. The cerebral herniation syndrome is the only situation in which hyperventilation is still indicated. Bilateral dilated and fixed pupils usually are a sign of brainstem injury and are associated with greater than 90% mortality. A unilateral dilated and fixed pupil has been associated with good recovery in up to 54% of patients. Remember that hypoxemia, orbital trauma, drugs, lightning strike, and hypothermia also affect pupillary reaction, so take this into account before beginning hyperventilation. If the patient has signs of herniation (as listed earlier) and the signs resolve with hyperventilation, you should discontinue the hyperventilation. Hyperventilation, although known to cause ischemia, may decrease brain swelling temporarily. Although a desperate measure, this might buy enough time to get the patient to surgery that might be life saving. Call ahead so that a neurosurgeon can be available and the operating room prepared by the time you arrive at the hospital. Facial wounds can range from minor contusions, abrasions, and lacerations to wounds that can be fatal from airway compromise or hemorrhagic shock. Most bleeding can be controlled by direct pressure, but some hemorrhage from the nose or pharynx can be life threatening and impossible to control in the prehospital setting. Nasal fractures are the most common fractures of facial bones and rarely are associated with severe hemorrhage. Fractures of the bones of the face and jaw are common, and the greatest danger is airway compromise caused by swelling and bleeding or loss of facial stability. Treatment of eye trauma in the field should be gentle irrigation with normal saline if needed for chemicals and then application of an eye shield. If there is a possible open globe, characterized by an irregularly shaped pupil, do not irrigate. Do not allow any pressure on the globe itself to prevent extrusion of the eye contents. Scalp Wounds the scalp is highly vascular and often bleeds briskly when lacerated. Because many of the small blood vessels are suspended in an inelastic matrix of supporting tissue, the normal protective vasospasm that would limit bleeding is inhibited, which may lead to prolonged bleeding and significant blood loss. Though an uncommon cause of shock in an adult, a child may develop shock from a briskly bleeding scalp wound, due to a smaller blood volume. Most bleeding from the scalp can be easily controlled in the field with direct pressure if your exam reveals no unstable fractures under the wound. Suspect an underlying skull fracture in adults who have a large contusion or darkened swelling of the scalp. There is very little that can be done for skull fractures in the field except to avoid placing Impaled object direct pressure on an obvious depressed or compound skull fracture. The real concern is that the amount of force that can cause a skull fracture may cause a brain injury.

Purchase pentoxifylline 400mg on line

Several investigators consider so-called "triple signal intensity" sign juvenile arthritis in back cheap 400 mg pentoxifylline mastercard, because of a combination of cystic and solid elements, fibrous tissue, hemorrhage, and hemosiderin deposition, as the most characteristic for this tumor. Treatment includes a wide local resection, followed with adjuvant chemotherapy with combination of Adriamycin, cisplatin, vincristine, doxorubicin, and ifosfamide. Postoperative radiation therapy is reserved for the patients in whom surgical intervention was not able to ascertain clear margins of resection. It may arise as a primary synovial tumor, or it may develop as a malignant transformation of synovial (osteo)chondromatosis. The concept of malignant degeneration of synovial chondromatosis is still controversial and the entity is rare, with fewer than 40 well-documented cases on record. These malignancies show a slight predominance in men, and patients range in age from 25 to 70 years. The symptoms include pain and swelling, with duration in most patients exceeding 12 months. In patients with primary synovial (osteo)chondromatosis, malignant transformation to synovial chondrosarcoma should be clinically suspected if there is development of soft tissue mass at the site of the affected joint. Radiologically, the presence of chondroid calcifications within the joint, destruction of the adjacent bones, and a soft tissue mass are highly suggestive of a synovial chondrosarcoma. In patients with documented primary synovial (osteo)chondromatosis, a soft tissue mass and destructive changes in the joint should suggest the development of a secondary synovial chondrosarcoma. The histopathologic distinction between primary synovial chondromatosis and secondary malignancy in synovial chondromatosis has been a matter of dispute. Manivel and associates suggested that histologic features equivalent to those of grade 2 or 3 central chondrosarcoma must be present before chondrosarcoma arising in synovial chondromatosis can be diagnosed. Occasional foci of increased cellularity showing hyperchromatic atypical cells, consistent with grade 1 chondrosarcoma, should not be sufficient evidence for a malignant change in synovial chondromatosis. Bertoni and coworkers have attempted to develop criteria for making this crucial distinction. The distinguishing features of synovial chondrosarcoma include the following: tumor cells arranged in sheets, myxoid changes in the matrix, hypercellularity with crowding and spindling of nuclei at the periphery, necrosis, and permeation of bone trabeculae. Remarking on the danger of misinterpreting synovial chondromatosis as chondrosarcoma on both radiographic and histopathologic examination, Bertoni and colleagues singled out pulmonary metastases as the only distinguishing feature. A: Anteroposterior radiograph of the left hip of a 37-year-old man shows an osteolytic lesion in the femoral neck bordered laterally by sclerotic margin (arrows). B: Scintigraphic (blood pool) examination demonstrates increased vascularity to the left hip joint (open arrows). Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the right foot of a 57-year-old woman show a large soft tissue mass containing calcifications, affecting mainly the plantar aspect of the foot. Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the left knee of a 34-year-old man show a large soft tissue mass adjacent to the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle containing calcifications. Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the right ankle of a 64-year-old man with a long history of synovial chondromatosis show a large soft tissue mass on the dorsal aspect of the ankle joint, eroding the talus. A: the chondrocytes with clearly pleomorphic and occasionally large nuclei (lower right corner) are unevenly distributed. The main differential diagnosis is between synovial chondrosarcoma and synovial (osteo)chondromatosis. Frequently, the imaging findings in both conditions are similar, although the development of destructive changes around the affected joint favors synovial chondrosarcoma. However, these destructive changes should be differentiated from periarticular erosions occasionally present in synovial chondromatosis. Intra-articular low-grade myxoid liposarcoma and high-grade intra-articular liposarcoma, both tumors located within the knee joint, have been reported. Extra-osseous localized non-neoplastic bone and cartilage formation (so-called myositis ossificans). Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip joint (review of the literature and report of personal case material). An immunohistological study of giant-cell tumor of bone: evidence for an osteoclast origin of the giant cells. Dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica: radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging features and clinical outcome of complete and incomplete resection. Giant cell tumor of bone with pulmonary metastases: six case reports and a review of the literature. Malignant giant cell tumor of the tendon sheaths and joints (malignant pigmented villonodular synovitis). Synovial chondromatosis of the hip: evaluation with air computed arthrotomography. Intra-articular synovial chondromatosis of shoulder with extra-articular extension. Treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis with yttrium-90: changes in immunologic features. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip: review of radiographic features in 58 patients. Synovial hemangioma: report of 20 cases with differential diagnostic considerations. Particular imaging features and customized thermal ablation treatment for intramedullary osteoid osteoma in pediatric patients. Giant-cell tumor of tendon sheath origin: a consideration of bone involvement and report of 2 cases with extensive bone destruction. Localized nodular synovitis of the knee: a report of two cases with abnormal arthrograms. Synovial hemangioma: imaging features in eight histologically proved cases, review of the literature, and differential diagnosis. Radiology of giant cell tumors of bone: computed tomography, arthrotomography, and scintigraphy. Fibrous xanthoma of synovium (giant-cell tumor of tendon sheath, pigmented nodular synovitis). Malignant transformation of extra-articular synovial chondromatosis: report of a case. Synovial sarcoma: a clinical, pathological, and ultrastructural study of 26 cases supporting the recognition of monophasic variant. Diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the foot and ankle treated with surgery and radiotherapy. Pigmented villonodular synovitis and related lesions: the spectrum of imaging findings. Pigmented villonodular synovitis and giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath: radiologic and pathologic features. Pigmented villonodular synovitis and tenosynovitis, a clinical epidemiologic study of 166 cases and literature review. Primary malignant giant cell tumor of bone: a study of eight cases and review of the literature. Treatment of diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee with combined surgical and radiosynovectomy. Chondrosarcoma complicating synovial chondromatosis: findings with magnetic resonance imaging. Bullous erythema nodosum leprosum masquerading as systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case report. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath and synovial membrane).

Purchase pentoxifylline visa

The pathologist should follow the recommendations made by Churg and Cagle to make a diagnosis of atypical mesothelial proliferation and let the clinician decide whether or not he/she will perform a new biopsy or await appropriate treatment arthritis in neck buy pentoxifylline 400mg on line. In a few publications patients have tissue asbestos levels similar to those with pleural plaques. Patients with diffuse pleural fibrosis have levels intermediate between those of patients with plaques and patients with asbestosis. Autopsied patients had more than 10 000 asbestos bodies in the lung, which indicated heavy asbestos exposure. These results suggest that rounded atelectasis may appear after high-dose exposure to asbestos. Pathology of the invagination was significantly associated with pleural thickening (P < 0. Atypical mesothelial hyperplasia with loss of cohesion of cells, increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratios and mild submesothelial hyperplasia. Note, even at this magnification, the nuclear hyperchromatism and the pseudoinvasion in the center of the field (saffron counterstain). There are apparent mesothelial foci deep in the pleura and this lesion requires multiple levels and clinico-pathological correlation before a diagnosis is made. Atypical mesothelial hyperplasia, where the reactive mesothelial cells extend deep and are close to fat but not definitely surrounding it. Common architectural patterns were single layer, stratified and papillary proliferations. There is no clear-cut morphological delineation between these last three different phases of carcinogenesis. No reliable immunohistochemical markers help to differentiate reactive hyperplasia from preneoplasia. Contrary to lung cancer, the exact sequence of the diverse morphological and molecular alterations is unknown. Half the cases progressed after 1 year and were probably mesotheliomas at the time of initial biopsy and represented sampling problems. Among the remaining cases, the mesothelioma arose after an interval free of disease of 3 to 13 years (unpublished data, Professor Galateau Salle). They showed superficial mesothelial proliferation composed of a single row of mesothelial cells with a "picket fence" appearance may define an in situ mesothelioma in the presence of an invasive mesothelioma in the vicinity. Full-thickness cellularity and cells entering in the parietal fat are almost always malignant. Recently a case report described mesothelial cells in dermal vessels associated with a huge umblical hernia. Most of the vessels were filled with glomeruloid- like and solid aggregates of polygonal cells, reminiscent of lymphovascular invasion or a vascular neoplasm at lower magnification. These aggregates were composed of the same cellular and stromal constituents present within the hernial sac. Reactive mesothelial hyperplasia with some hyperplastic mesothelial cells to the right of the field, amidst some mild chronic inflammation and much edema. Ancillary techniques in reactive mesothelial hyperplasia versus neoplastic processes Some immunohistochemical markers could lead to a diagnosis of malignancy and others may give more confidence to the pathologist in the diagnosis of a neoplastic process. Positive staining with broad-spectrum anti-keratin is not specific for malignancy and is seen in active mesothelial proliferation. Nevertheless, keratin is extremely helpful in showing the distribution of the mesothelial cells ("raining down" pattern), highlighting linear arrays parallel to the pleural surface (favoring a benign process) and subtle penetration into fat or distal alveoli of the lung parenchyma (suggesting mesothelioma). Eighteen percent of mesotheliomas were desmin-positive, with 86% positivity in reactive mesothelial cells. However, the range of p53 expression in other studies is variable and Attanoos et al. A statistical analysis, based on the interobserver agreement of some morphological criteria correlated with the follow-up of 52 cases, detected some promising criteria that might predict an aggressive clinical course. In genuine invasion by mesothelioma, the number of cells is more extensive than seen in entrapped reactive mesothelial cells. In such cases, a diagnosis of superficial mesothelial proliferation of undetermined malignancy should be given to avoid overdiagnosis. Simple, non-branching glands, often with a flattened mesothelium, are often benign. The formation of branching glands and/or papillae raises the suspicion of malignancy. Papillae or branching glands are characteristic of some forms of epithelial mesothelioma. Benign processes commonly appear atypical and mesotheliomas are often deceptively monotonous. Cytological atypia is therefore often unhelpful in separating benign from malignant processes. As with all new studies, these results need validating in a larger series of cases. Mesothelin is one of the more specific markers in the serum or in pleural and/or peritoneal effusion fluid and might be useful for the diagnosis and assessment of tumor progression. These are notoriously inaccurate, especially from the histopathological viewpoint. If asbestos exposure were mentioned in mesothelioma deaths, the detection rates in future epidemiological studies may improve. In one study, death certificates reported the diagnosis of histologically confirmed mesothelioma accurately. The British mesothelioma death rate is now the highest in the world, with 1749 deaths in men (1 in 40 of all male cancer deaths below 80 years of age) and 288 in women in 2005. The reduction in asbestos use since the mid-1970s has been followed 20 years later by a rapid fall in the number of mesothelioma deaths at 35:49 years of age in British men (289 in 1990:1994, 122 in 2000:2004), although the decline is less in women (56 in 1990:1994, 39 in 2000:2004). The number of deaths is predicted to peak at between 1950 and 2450 deaths per year, between 2011 and 2015. The eventual death rate will depend on the background level and any residual asbestos exposure. Between 1968 and 2050 there will have been approximately 90 000 deaths from mesothelioma in Great Britain, over two-thirds occurring after 2001. For the worst affected cohorts: men born in the 1940s: mesothelioma may account for around 1% of all deaths. Willis,493 one of the authorities on human tumors, gave such strict criteria for the identification of this tumor that it was virtually impossible to diagnose. Pleural mesothelioma is probably due to accumulation of fibers in the pleura, the route having been documented previously. Approximately 90:95% of these tumors arise in the pleural cavity and 5:10% in the peritoneum. Rarely, they are seen in the pericardium, tunica vaginalis,497:499 ovary, testis (see below) and liver. Mesothelioma has an incidence rate of 193 per 100 000 in the period 2000:2005 in Australia. Forty years after the crocidolite mine and mill at Wittenoom, Western Australia, had closed, there is still a high toll from cancer among the former female residents of the town and company workers. The incidence in New South Wales, Australia, increased for both genders by approximately 15-fold. Latency periods between first exposure to asbestos and development of mesothelioma are mostly longer than 40 years. An inverse relationship exists between intensity of asbestos exposure and length of the latency period. Mesothelioma generally develops after long-time exposures to asbestos and probably duration of exposure. While a leveling-off in mesothelioma incidence has been registered in some countries, a worsening of the epidemic is predictable in large parts of the world, especially the developing world. They suggested male mesothelioma deaths in Western Europe would almost double over the next 20 years, from 5000 in 1998 to about 9000 around 2018. They then expected a decline, with a total of about a quarter of a million deaths over the next 35 years.

Buy online pentoxifylline

For Class I bone resorption arthritis in back spondylosis generic pentoxifylline 400 mg, implants of regular or even wide platform diameter may be placed, because the bone loss is minimal in both width and height (recent tooth loss). Detailed description of these procedures is beyond the scope of this book, but a brief overview of each of these techniques is provided in the following sections so that the reader can become familiar with the options available for alveolar ridge augmentation in areas of compromised anatomy. Instead, a modi ed procedure called the two-stage horizontal alveolar bone splitting using pedicled sandwich plasty technique is recommended. The ostoetomies should be deep enough to reach the cancellous bone layer and should be well connected. Proceeding with implant placement during stage-one surgery is not recommended, because the full-thickness ap from the rst surgery will disrupt the blood supply to the bone that is provided via the periosteum, which might lead to bone segment necrosis when the bone segment is mobilized during implant placement. A healing period of at least 28 days is observed for the purpose of reattaching the periosteum layer to the bony surface. It is less challenging than using a particulate bone graft and a membrane alone, because there is less chance of collapse due to soft tissue pressure or pressure from removable provisional appliances. However, proper patient selection for this method is important, and primary closure must be achieved, among many other factors, for a successful outcome. This angulation will lead to many biomechanics-related complications, including fracture of the restoration, retaining screw, abutment, or implant body; osseous destruction by unfavorable loading; and dif culties with oral hygiene because of the ridge lap pontic design. Friberg et al28 reported a 7 month evaluation of 10 patients and found hypesthesia or paresthesia in 30% of them. Rosenquist30 noted that 6 of 100 patients had either diminished or complete lack of neurosensation at 18 months postoperatively. Jensen et al31 reported that 10% of the patients in their study had signs of neurosensory disturbance. Although in the majority of the cases affected sensation appears to be transient,27,35 risks regarding neurosensory disturbance should be considered and explained to the patient during treatment planning. Forcing movement of the mental nerve without rst excising these incisive nerves will damage it. However, excising these nerves will permanently eliminate the sensation of the roots anterior to the mental foramen, hence why it is so important that no teeth are present there. The procedure starts by exposing the nerve and carefully removing the bone around it using a piezotome tip. The lingual periosteum must not be injured, and thus a nger can be placed over the lingual mucosa to feel the piezotome cutting tip as it exits the bone. Complications with this procedure include risk of sensory nerve damage, failure of the graft to consolidate, and failure to achieve the required vertical dimension. The segment is then xated to the inferior intact mandibular bone with more screws, and the site is grafted with allograft bone material. Distance between external cortical bone and mandibular canal for harvesting ramus graft: A human cadaver study. Partial-thickness cortical bone graft from the mandibular ramus: A non-invasive harvesting technique. Mandibular cortical bone grafts part 1: Anatomy, healing process, and in uencing factors. Mandibular cortical bone graft part 2: Surgical technique, applications, and morbidity. Ramus or chin grafts for maxillary sinus inlay and local onlay augmentation: Comparison of donor site morbidity and complications. Variations in the posterior division branches of the mandibular nerve in human cadavers. Clinical recommendations for avoiding and managing surgical complications associated with implant dentistry: A review. Sensory outcomes of the anterior tongue after lingual nerve repair in oropharyngeal cancer. Repair of the lingual nerve after iatrogenic injury: A follow-up study of return of sensation and taste. The course and distribution of the inferior alveolar nerve in the edentulous mandible. Risk assessment of lingual plate perforation in posterior mandibular region: A virtual implant placement study using cone-beam computed tomography. Pedicled sandwich plasty: A variation on alveolar distraction for vertical augmentation of the atrophic mandible. Inferior alveolar nerve repositioning in conjunction with placement of osseointegrated implants. Fixture placement posterior to the mental foramen with transposing of the inferior alveolar nerve. Repositioning the inferior alveolar nerve for placement of endosseous implants: Technique note. Implant placement in combination with nerve transposing: Experience with the rst 100 cases. Nerve transposing and implant placement in the atrophic posterior mandibular alveolar ridge. Does the risk, of complication make transposing the inferior alveolar nerve in conjunction with implant placement a 'last resort' surgical procedure Endosseous implant placement in conjunction with inferior alveolar nerve transposing: An evaluation of neurosensory disturbance. Reconstruction of atrophic anterior mandible using piezoelectric sandwich osteotomy: A case report. Piezoelectric vertical bone augmentation using the sandwich technique in an atrophic mandible and histomorphometric analysis of mineral allografts: A case report series. Use of the sandwich osteotomy plus an interpositional allograft for vertical augmentation of the alveolar ridge. Piezoelectric and conventional osteotomy in alveolar distraction osteogenesis in a series of 17 patients. Surgical management of the partially edentulous atrophic mandibular ridge using a modi ed sandwich osteotomy: A case report. This chapter also describes the anatomical manifestations of different bone resorption patterns in the anterior mandible and the proper treatment planning for each, as well as the anatomical considerations for harvesting a block graft from the chin. Distance B is the actual distance available above the nerve, and it is considerably greater than distance A (usually by 2 to 5 mm). In the middle of the alveolar bone, the nerve is considerably lower than the superior border of the foramen. On the right side of the mandible, however, the desired implant will invade the mental foramen level; therefore, to be at a safe distance from the anterior loop, the pilot drill (ie, the initial osteotomy) should be located 7 mm from the mesial border of the mental foramen. The initial osteotomy should always be placed 7 mm anterior to the most mesial border of the mental foramen if the implant is to invade the level of the mental foramen apicocoronally. In such cases, care should be taken not to harm the mental nerve; this can be accomplished by placing the midcrestal incision slightly toward the lingual and by gently re ecting a full-thickness ap until the foramen is identi ed. It was decided that 12 mm away from the midline was a safe area in which to drill, thus avoiding the risk of damaging the mental nerve by the scalpel. A periodontal probe (f) was used after each drill to verify that the osteotomy was completely within bone. Because the vertical cantilever on the future prosthesis would be extensive, the patient was treatment planned for a Locator overdenture (Zest Anchors). The Locator caps will allow the prosthesis to disengage its attachments before transferring too much stress onto the implants and creating a weak link in the prosthesis-implant interface. However, in some cases the incisive nerve presents as a true canal with large lumen (0. The existence of the canal can be problematic; as an extension of the inferior mandibular nerve, it should be considered to contain the same neurovascular elements,5 and thus osteotomies should not be made though this canal. Although this canal is only 8 to 10 mm above the inferior border of the mandible, it may still lie in the pathway of the osteotomy in a severely resorbed mandible. Cross-sectional images of the right mental foramen (b), mandibular right canine (c), left mental foramen (d), and mandibular left canine (e) are shown. On the left side, the mental foramen is located between the rst molar and the second premolar, and the cross-sectional image of the canine does not show an incisive mandibular canal.

Discount pentoxifylline 400 mg otc

A V-shape radiolucent defect in the lateral aspect of the physis arthritis at 25 buy pentoxifylline 400 mg with mastercard, known as a Gage sign (arrow), indicating a "head-at-risk" is demonstrated in this 7-year-old girl. Treatment the therapy is individualized on the basis of the clinical and imaging findings, including the age of onset, the range of motion in the hip joint, the extent of femoral head abnormalities, and the present or absence of femoral deformity and lateral subluxation. Although some orthopedic surgeons have suggested eliminating weight bearing to prevent deformity of the femoral head, prevention requires measures that maintain the femoral head within the acetabulum (containment), thereby preventing extrusion and subluxation, as well as obtaining a full range of motion in the hip joint. In this respect, Salter advocated full weight bearing together with containment methods of treatment. The surgical treatment consists of femoral (varus derotational) or pelvic (innominate bone) osteotomy, aimed at covering the femoral head with the acetabulum. Osteonecrosis of the femoral condyle after arthroscopic reconstruction of a cruciate ligament. Core decompression and conservative treatment for avascular necrosis of the femoral head: a meta-analysis. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head in patients with inflammatory arthritis on asthma receiving corticosteroid therapy. The importance of increased intraosseous pressure in the development of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: implications for treatment. Response: the role of core decompression in treatment of ischemic necrosis of the femoral head. The natural history of untreated asymptomatic hips in patients who have nontraumatic osteonecrosis. Systemic fat embolism after renal transplantation and treatment with corticosteroids. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphism in patients with nontraumatic femoral head osteonecrosis. Osteonecrosis in patients receiving dialysis: report of two cases and review of the literature. The radiolucent crescent line-an early diagnostic sign of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. The fate of nontraumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head: a radiologic classification to formulate prognosis. Risk factors of avascular necrosis of the femoral head in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus under high-dose corticosteroid therapy. Prediction of collapse with magnetic resonance imaging of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Magnetic resonance imaging of osteonecrosis in divers: comparison with plain radiographs. Is avascular necrosis of the femoral head the result of inhibition of angiogenesis Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: natural history and magnetic resonance imaging. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head after intramedullary nailing of a fracture of the femoral shaft in an adolescent. Avascular necrosis after scaphoid fracture: a correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head with free vascularized fibular grafting. The cause of this condition is unknown, but it is probably a multifactor disorder with genetic, humoral, biomechanical, and environmental factors. Bateson has demonstrated convincingly that Blount disease and physiologic bowleg deformity are part of the same condition, which is influenced by early weight-bearing and racial factors. On the basis of a study of South African black children, among whom there is an increased incidence of this disorder, Bathfield and Beighton have suggested that its cause might be related to the custom of mothers carrying children on their backs. Two forms of Blount disease have been identified: infantile tibia vara, which is usually bilateral and affects children younger than 10 years of age, with onset most commonly between ages 1 and 3 years, and adolescent tibia vara, which is usually unilateral and occurs in children between the ages 8 and 15 years. The course of the adolescent form of disease is less severe and its incidence less frequent than that of the infantile form. Regardless of its variants, Blount disease must be differentiated from other causes of genu varum, such as in variety of arthritides. Imaging Features Radiographically, the early stages of Blount disease are marked by hypertrophy of the nonossified cartilaginous portion of the tibial epiphysis and hypertrophy of the medial meniscus, which represent compensatory changes secondary to growth arrest at the medial aspect of the physis. The medial aspect of the tibial metaphysis is characteristically depressed, exhibiting an abrupt angulation and formation of a beaklike prominence, which is associated with cortical thickening of the medial aspect of the tibia. Because of the sharp angulation of the metaphysis and adduction of the diaphysis, the tibia assumes a varus configuration. As the metaphysis and growth plate become depressed, the cartilage decreases in height. In advanced stages of the disease, there is premature fusion of the growth plate on the medial side. The presence of fusion is important information for surgical planning because either resection of the bony bridge or epiphysiodesis (fusion of the physis) would be required in addition to corrective osteotomy. In the past, double-contrast arthrography was a valuable technique in the imaging evaluation of Blount disease, because it permitted visualization of nonossified cartilage of the medial plateau. A: Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee of a 4-year-old girl with unilateral congenital tibia vara shows depression of the medial tibial metaphysis associated with a beak formation and medial slant of the tibial epiphysis. A varus deformity of the tibia, associated with irregularity of the growth plate and a small beak at the medial metaphysis; usually seen in children from 2 to 3 years of age. Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee of an 8-year-old girl shows the typical changes of congenital tibia vara. There is, in addition, a fusion of the medial portion of the growth plate (arrow). A definite depression of the medial portion of the metaphysis, associated with slanting of the medial aspect of the epiphysis; usually seen in children from 2 to 4 years of age. Progression of the varus deformity and a very prominent beak, with occasional fragmentation of the medial portion of the metaphysis; seen in children between 4 and 6 years of age. Marked narrowing of the growth plate and severe slanting of the medial aspect of the epiphysis, which shows an irregular border; usually seen in children between 5 and 10 years of age. Marked deformity of the medial epiphysis, which is separated into two parts by a clear band, the distal part having a triangular shape; seen in children between 9 and 11 years of age. An osseous bridge between the epiphysis and metaphysis and possible fusion of the triangular fragment of the separated medial epiphysis to the metaphysis; seen in children between 10 and 13 years of age. Recently, Smith introduced a simplified classification of Blount disease in attempt to relate the grade of deformity to the need for treatment. His scheme comprises four grades: grade A, potential tibia vara; grade B, mild tibia vara; grade C, advanced tibia vara; and grade D, physeal closure. A: Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee of a 10-year-old boy demonstrates the classic appearance of this condition, as evident in the depression of the medial metaphysis associated with a beak formation and slanting of the medial tibial epiphysis (arrow). B: Arthrographic spot film shows contrast outlining the thickened nonossified cartilage of the medial tibial plateau (open arrow). C: Anteroposterior radiograph of the right knee of a 4year-old boy shows more advanced deformities of the medial tibial epiphysis and metaphysis. D: Double-contrast arthrogram shows hypertrophy of the medial meniscus and thick nonossified articular cartilage at the medial aspect of the proximal tibial epiphysis. Fluoroscopic spot film of a knee arthrogram in a 4-year-old girl shows hypertrophy of the medial aspect of the proximal tibial articular cartilage and an enlarged medial meniscus. A: Anteroposterior radiograph of the left knee demonstrates the characteristic depression of the medial tibial plateau and medial epiphyseal fragmentation (arrow). B: Coronal T1-weighted image demonstrates the irregular, depressed epiphyseal cartilage of the medial tibial plateau (arrowhead) with partial calcification and fragmentation of the depressed medial epiphyseal cartilage (arrow). Note the irregularity and widening of the growth plate, not evident on the radiograph (double arrows). If the deformity continues to progress despite such treatment, a high valgus tibial osteotomy may be required to achieve normal alignment of the limb; usually, correction of a rotary deformity requires an osteotomy of the proximal fibula as well. Boys are affected more often than girl, and children of both genders with this disorder are often overweight.