Cheap voltaren 100mg online

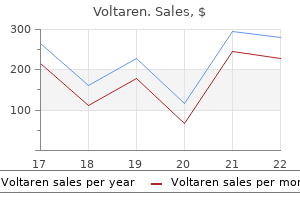

Translation has proven to be particularly important to the genetic engineer since many antibiotics target translation as their mechanism of inhibiting bacterial growth arthritis in dogs in winter purchase generic voltaren on-line. The protein chain contains information that directs post-translational processes and cellular compartmentalization in eukaryotes. Many proteins, in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, have this residue removed by an enzyme called methionine aminopeptidase such that the final protein sequence begins with the amino acid encoded by the second codon (Bradshaw, Briday and Walter, 1998). The 30S ribosomal subunit binds directly to this sequence and then recruits the 50S subunit. Many eukaryotic proteins are, however, destined for a particular compartment of the cell. The polypeptide itself encodes the information required for its final destination. As far back as the 1950s, it was noted that if a bacteriophage was prepared from a particular strain of E. The enzyme displayed a number of complex activities that made it difficult to study (Table 2. More than 900 restriction enzymes have now been isolated from over 230 species of bacteria. The letters were, by convention, written in italics, but recently this has changed so that they are now written in plain font (Roberts et al. The numbers following the nuclease name indicate the order in which the enzyme was isolated from the bacterial strain. Like many restriction enzymes, the genes encoding both the nuclease and the modifying enzymes are adjacent to each other in the genome. The methylated base presumably flips back into the helix when the enzyme dissociates. Reproduced from Blumenthal and Cheng (2001) by permission of Xiaodong Cheng (Emory University) can then be a substrate for the enzyme-catalysed chemical reaction (Cheng and Roberts, 2001). The methylation of adenine at this point does not affect its ability to base pair with thymine. The various methylase, restriction and specificity subunits are colour coded as indicated 2. The slow remethylation of oriC after one round of replication delays another round until the first is complete (von Freiesleben et al. The Dam- and Dcm-dependent methylation may interfere with cleavage by restriction endonucleases with recognition sites partially or completely overlapping such methylation sites. Once it encounters its particular recognition sequence, the restriction enzyme undergoes a large conformational change, which activates the catalytic sites. The positions of these two cuts, both in relation to each other, and to the recognition site itself, are determined by the individual restriction enzyme. The recognition site of each enzyme is shown, together with the cleavage site, indicated by the blue line. When the enzyme encounters this sequence, it cleaves each backbone between the G and the closest A base residues (Mertz and Davis, 1972). Once the cuts have been made, the resulting fragments are held together only by the relatively weak hydrogen bonds that hold the four complementary bases to each other. The cellular origin, or even the species origin, of the sticky ends does not affect their stickiness. Any particular 6 bp target would be expected to occur once every 46 (4096) bp, and an 8 bp target every 48 (65 536) bp. As we saw in Chapter 1, Chargaff noted that the amount of C + G residues in different organisms was different to the amount of A + T. The final step is a nucleophilic attack by the 3 -hydroxyl group on this activated phosphorus atom. In the vector the recognition sites for the restriction enzymes are located close to each other. Treating the vector with a phosphatase enzyme after it has been cut with the restriction enzymes, however, can prevent this. Phosphatases catalyse the removal of 5 phosphate groups from nucleic acids and nucleotide triphosphates. The basics of cloning into a plasmid vector containing a single unique restriction enzyme recognition site. The ligation of a compatible insert into this vector will result in the ligation of only the 5 -ends of the insert with the vector. The 3 -end of the insert (a hydroxyl group) and the 5 -end of the vector (also a hydroxyl group) will be unable to ligate. Other sites can be made blunt by either cleaving off the overhanging ends with a nuclease. Additionally, as we have already seen, bacteriophages can efficiently infect various strains of E. The different plasmids and bacteriophages that are used as vectors are described detail in Chapter 3. These markers, usually antibiotic resistance genes, will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. This chemical transformation treatment was also subsequently shown to allow plasmids to enter bacterial cells, at varying levels of efficiency. Increased transformation efficiencies have been observed using high voltage electric pulses in a process called electroporation, and using a gene gun. This single molecule may be amplified many times within the host, but all of the resulting molecules are identical. Essentially, the cells are grown to mid-log phase, harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a solution of calcium chloride. Nutrient medium is then added to the cells and they are allowed to grow for a single generation to allow the phenotypic properties conferred by the plasmid. Cells are treated with an electrical pulse, which mediates the formation of pores. The efficiency of transformation is governed by a number of host-specific and other factors, but the molecular processes by which transformation occurs are not well understood, and conditions by which efficient transformation can take place are determined empirically. If a suitable electric field pulse is applied, then the electroporated cells can recover, with the electropores resealing spontaneously, and the cells can continue to grow. The use of electroporation to transform both bacterial and higher cells became very popular throughout the 1980s. The mechanism by which electroporation occurs is not well understood and hence, like chemical transformation, the development of protocols for particular applications has usually been achieved empirically by adjusting electric pulse parameters (amplitude, duration, number and inter-pulse interval) (Ho and Mittal, 1996; Canatella et al. The pulse amplitude and duration are critical if electropores are to be induced in a particular cell. The product of the pulse amplitude and duration has to be above a lower limit threshold before pores will form, beyond which the number of pores and the pore diameter increase with the product of amplitude and duration. An upper limit threshold is eventually reached, at high amplitudes and durations, when the pore diameter and total pore area are too large for the cell to repair.

Glycerin Monolaurate (Monolaurin). Voltaren.

- The common cold, the flu (influenza), herpes, shingles, and other conditions.

- Dosing considerations for Monolaurin.

- What is Monolaurin?

- How does Monolaurin work?

- Are there safety concerns?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=97093

Cheap voltaren 50mg on-line

Diagnosis relies on careful clinical assessment arthritis pain lying down buy 100 mg voltaren mastercard, complemented, in most cases, by appropriate brain or spinal imaging. Current stroke management mandates urgent evaluation of unilateral limb weakness However, focal limb weakness can be caused by many non-stroke pathologies and these should not be overlooked in the rush to definitive management. Saddle anaesthesia, bilateral leg pain, urinary retention and reduced anal tone suggest cauda equina syndrome, and should prompt urgent imaging. Other causes fe e fre e Encephalitis may cause limb weakness as part of a constellation of central neurological symptoms including confusion, seizures and co m be bulbar involvement but sensory features are absent. Migraine occasionally causes limb weakness (hemiplegic migraine) but this is a diagnosis of exclusion. If the current presentation of limb weakness is confined to one side of the body assess as per unilateral limb weakness (this includes patients with contralateral facial weakness). Otherwise, continue on the current diagnostic pathway, even if signs are markedly asymmetrical. Otherwise, seek urgent neurological review and continue to assess as described below. To assess for a sensory level test light touch and pinprick sensation in each dermatome on both sides. If sensation is abnormal in the lower dermatomes, move progressively upwards through the truncal/upper limb dermatomes until it normalizes. Obtain specialist neurological input in any suspected case of motor neuron disease or multiple sclerosis, or if the cause remains unclear. C Ulnar nerve D Common bo Flexor carpi ulnaris o oo o Motor k ok s Limb weakness bilateral limb weakness: step by-step assessment ks multiplex; if suspected, arrange neurophysiological assessment and investigate for an underlying malignant vasculitic or infiltrative disorder. At risk groups include the elderly, cirrhotic, malnourished patients and ethnic minority groups, but this is overall a more common problem than is recognized. No re Yes Consider spaceoccupying lesion, meningoencephalitis c Likely stroke See Further assessment of stroke (p. No Consider plexopathy, multi-root compression, stroke, motor neuron disease, migraine, functional weakness r Yes Radiculopathy / mononeuropathy. Exclude a unilateral cord lesion if there is dissociated sensory loss (ipsilateral proprioception/ vibration; contralateral pain/temperature) or a clear sensory level. If weakness is confined to a single limb, consider mu ti-level root compression (see Table 22. Otherwise, consider mononeuritis multiplex (see above), an atypical presentation of motor neuron disease (usually bilateral) or functional weakness. Investigate for an unusual cause of stroke in younger patients without vascular risk factors. It predominantly affects young and middle-aged adults, often following bending or lifting. The pain tends to be worse during activity, relieved by rest, and is not associated with sciatica, leg weakness, sphincter disturbance, claudication or systemic upset. In most cases, the pain resolves after a few weeks but recurrence or persistent low-grade symptoms are relatively common. Risk factors for developing chronic, disabling pain include depression, job dissatisfaction, disputed compensation claims and a history of other chronic pain syndromes. Ankylosing spondylitis typically presents in early adulthood with an insidious onset of progressive back pain and stiffness over months to years. A thorough history and examination, supplemented where necessary by spinal imaging, is critical to identify patients with low back pain who have serious and/or treatable pathology. Patients often have longstanding, non-specific low back pain before developing dull or cramping discomfort in the buttocks and thighs precipitated by prolonged standing walking and eased by sitting or lying down (neurogenic claudication). A patient with localized low back pain following trauma requires imaging to evaluate instability and involvement of the spinal canal/cord. Yes Spinal X ray Vertebral fracture Spinal tumour / other cause Refer to rheumatologist o 1 Bilateral lower limb neurology, sphincter dysfunction or perianal sensation Pain radiating from the back down the front of the leg to the knee indicates L2/ L3/L4 nerve root tension. Consider further investigation if there are any red flag features, other than age (see below). B When femoral roots are tightened by flexion of the knee +/- extension of the hip pain may be felt in the back. Suspect lumbar spinal stenosis if the patient is >50 years with a slow progressive onset of symptoms and/or features of neurogenic claudication (see below). Suspect lumbar disc herniation in acute-onset radicular pain, especially if the nerve stretch test is positive. If pain persists, look for features of depression and explore other potential psychosocial factors. Spinal imaging is unlikely to be helpful but seek specialist input if there are persistent or progressive disabling symptoms. Refer to rheumatology for further evaluation of possible inflammatory back pain if there are X-ray features of spondylitis. Consider neurogenic claudication if low back pain is accompanied by bilateral thigh or leg discomfort. Evaluate first for vascular claudication if the patient has a history of atherosclerotic disease, >1 vascular risk factor. Younger patients can usually be rapidly categorized into an underlying aetiology, but evaluation of elderly patients is more complex. Moreover, mobility problems may be self-reinforcing, as reduced activity leads to loss of muscle function and confidence. A thorough, systematic approach is essential to identify adverse consequences of immobility, serious underlying pathology and potentially reversible contributing factors. In these cases, assessment should focus, initially, on the underlying primary problem to determine the cause. Some patients with apparent falls may actually be experiencing blackouts and, again, this necessitates a different diagnostic approach. Acute illness or drug reaction Some falls are the unavoidable consequence of a trip or stumble. In the absence of significant injury, recurrent mobility problems or other concerns these patients do not require detailed assessment. Multifactorial mobility problems In patients with recurrent falls or other chronic mobility problems, there is often no single identifiable cause but rather multiple contributing factors. In those with chronic underlying mobility problems, a relatively minor insult may lead to a major deterioration in mobility. No Primary prob em = focal limb weakness / blackout / dizziness / acute joint pain Yes Yes Yes Evaluate and treat: fractures / wounds / head injury / pain / hypothermia / rhabdomyolysis / dehydration 2 Accidental trip 3 re e No No Assess gait (Box 24. Assess the perfusion and function of any limb with bruising, deformity, pain or swelling and consider the need for X-rays. If there is a history of head injury, arrange neuroimaging if any of the features in Box 24. Otherwise, assess as in Chapter 10, but complete a full mobility assessment, especially if no specific disorder is identified.

50 mg voltaren mastercard

Laterally arthritis in fingers what is treatment cheap 50 mg voltaren with mastercard, the infratemporal fossa located below the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The medial pterygoid and lateral pterygoid muscles occupy the infratemporal fossa. On the left side, the medial and lateral pterygoids have been removed to expose the internal maxillary artery and the mandibular nerve (V1) as it exits from the foramen ovale. Also seen are the internal carotid artery, the tensor veli palatini, levator veli palatini, and the muscles of the eustachian tube. Laterally, the medial pterygoid plates form the lateral boundaries of the nasopharynx. Attached to the posterior margins of the medial pterygoid plates is the thick dense pharyngobasilar fascia. The bony orifice of the posterior choana is formed by the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the palatine bone. The numerous bony foramina located within and near the nasopharynx are important routes of extension or invasion of both benign and malignant lesions. Anteriorly, the sphenopalatine foramen transmits the sphenopalatine artery and is commonly the site of origin of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, which often expand the foramen and extend into the pterygopalatine fossa laterally. Thus, the nasopharyngeal roof extends down to the middle clivus in the midline, but is confined to the upper clivus by the longus capitis muscle on either side. The configuration of the nasopharynx is determined by the very tough pharyngobasilar fascia, which attaches to the base of the skull from the posterior margin of the medial pterygoid plate to the petrous part of the temporal bone immediately in front of the carotid foramina. The fascia forms an entirely closed and very resistant fibrotic chamber, which is perforated only by the passage of the eustachian tube. Eustachian Tube System and Soft Palate the eustachian tube is a prominent anatomic feature on the lateral nasopharyngeal wall. It connects the nasopharynx to the middle ear, is 3 to 4 cm long, and opens into the lateral wall of the nasopharynx immediately behind the medial pterygoid plate by an inverted J-shaped protuberance called the torus tubarius. Associated with this mucosa is a variable amount of lymphoid tissue, known as the nasopharyngeal tonsils or adenoids. The nasopharynx can be thought of as a fibromuscular sling suspended from the basisphenoid. The inner longitudinal layer consists of the salpingopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and stylopharyngeus. The tensor and levator veli palatini, which are muscles of the soft palate, also contribute to this layer at their superior ends. The outer circular layer at the level of the nasopharynx is formed by the superior constrictor, with the superior aspect of the middle constrictor overlapping it inferiorly. The median raphe of the superior constrictor is attached to the pharyngeal tubercle superiorly. Lateral to the pharyngeal tubercle on each side, the longus capitis muscle is attached to the middle and the lower clivus. The anterior surface of this muscle, which is convex forward on each side of the midline, also furnishes attachment to the pharyngobasilar fascia and the prevertebral fascia on the middle clivus. The border between the roof and posterior wall of the nasopharynx is sited at the. The torus tubarius is formed by the medial end of the cartilaginous tube elevating the overlying mucosa. The medial or posterior limb of the cartilage is longer than the lateral or anterior limb. The eustachian tube is bounded anteriorly and laterally by the tensor veli palatini and posteriorly and inferiorly by the levator veli palatini. The levator veli palatini originates from the quadrate area of the petrous bone and partly from the short limb of the cartilaginous eustachian tube and runs almost parallel to it. Along with the cartilaginous portion of the eustachian tube, the levator veli palatini passes directly to the soft palate through the sinus of Morgagni. Isotonic contraction of this muscle elevates the soft palate and expands the tubal orifice as it splays open the medial and lateral limbs. The tensor veli palatini originates from the scaphoid fossa of the sphenoid bone anterolateral to the levator veli palatini muscle. The tensor veli palatini muscle reaches the palate indirectly by hooking around the hamulus of the medial pterygoid and inserts into the median raphe. It opens the tube by traction on the lateral tubal membrane and the lateral limb of the cartilage. The recess is bounded anteriorly by the levator veli palatini, posteriorly by the longus capitis muscle, and its roof is attached to the thick connective tissue covering the foramen lacerum above. The posterolateral depth of the recess is separated from the cervical internal carotid artery by only a layer of fibroconnective tissue. The motor supply is derived from the nucleus ambiguous, by way of the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve, which supplies all pharyngeal muscles except the stylopharyngeus, which is the only muscle controlled by the glossopharyngeal nerve. Sensory innervation is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve, with the exception of a small patch behind the eustachian tube, which is supplied by the pharyngeal branch of V2. The cell bodies of these afferent fibers are located in their respective ganglia, with central connections to the nucleus of the tractus solitarius and the spinal tract of V. The parasympathetic secretomotor supply arise from the superior salivary nucleus, whose fibers travel from the brainstem via the nervus intermedius, through the geniculate ganglion, proceeding anteriorly in the greater superficial petrosal nerve, and reaching the pterygopalatine ganglion via the nerve of the pterygoid canal. Sympathetic fibers, as in the rest of the body, travel together with the blood vessels. The preganglionic cell bodies arise from the lateral column of T1 through T3, traveling up the sympathetic trunk to synapse in the superior cervical ganglion. Histology the epithelium of the nasopharynx is mainly pseudostratified ciliated columnar type near the choanae and adjacent part of the roof of the nasopharynx, becoming stratified squamous in the lower and posterior regions. Almost 60% of the nasopharynx is lined by stratified squamous epithelium derived from endoderm. Areas of transitional epithelium are encountered in the junctional zone of the roof and lateral walls. The transitional zone between the nasopharynx and oropharynx is lined by stratified columnar epithelium, which changes to the nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium of the oropharynx. Typical of respiratory mucosa, mucus production is by goblet cells, although there are seromucinous glands in the submucosa. Deep to the mucosa lies the lamina propria, which is frequently infiltrated by lymphoid tissue, which, in the child, forms a midline aggregation posteriorly of varying size, termed the adenoid (nasopharyngeal tonsil). These lymphoid aggregates, although found mainly in the lamina propria, may extend into the submucosa if hypertrophic. Branches are given off to supply the pharyngeal wall as it ascends, with a palatine branch passing over the superior edge of the superior constrictor, which supplies the soft palate and mucosa. The ascending palatine branch of the facial artery and the greater palatine and pterygoid branches of the internal maxillary artery also contribute. The sphenopalatine artery and its posterior septal branch contribute to the blood supply of the roof and choanal aspects of the nasopharynx. Venous drainage of the nasopharynx consists of two layers of venous plexuses, namely the submucous layer and the external pharyngeal plexus. These plexuses are continuous from the nasopharynx inferiorly into the oropharynx. The pharyngeal plexus of the nasopharynx drains laterally into the pterygoid plexus and downward into the internal jugular vein. Imaging Radiologic Anatomy Conventional radiographs yield limited information about the nasopharynx. These modalities are complementary and are often used together to demonstrate the full disease extent. A discrepancy of more than 5 mm between sides should prompt suspicion of a lesion. The cartilaginous end of the eustachian tube is usually of similar or lower signal intensity than surrounding muscle. Tubular tonsillar tissue present in this area may give a fairly intense signal depending on the amount of lymphoid tissue present and the effects of volume averaging.

Safe 50mg voltaren

One explanation could be related to the deposition of the spray in the nasal cavity arthritis in neck with dizziness buy discount voltaren 50 mg on line. In fact, it has been shown that only a small amount of nasally applied drugs reaches the olfactory epithelium, which is situated in an anatomically protected area of the nasal cavity. This situation can be slightly improved by the application of sprays in a "head-down-forward position" or devices that project the steroids directly into the olfactory cleft. Some antibiotics, such as macrolides, may be used for their additional specific immunomodulatory effects. Other Treatments In addition to the use of steroids and antibiotics, there are other treatments that have been proposed to restore olfactory loss. They include antileukotrienes, saline nasal lavages, dietary changes, acupuncture, antihistamine treatments, desensitization, and specific immunotherapy, such as omalizumab. However, these treatments still need further studies confirming therapeutic evidence. The surgical concept is to reduce the amount of inflammatory tissue and to open the blocked sinuses mechanically and restore the drainage of mucus. In most studies, however, the follow-up is only 1 year or less, and there is limited knowledge about the long-term success of surgery regarding the improvement of olfaction. To control the inflammatory disease of the ethmoid, the middle turbinate is often medialized or even partly resected to gain wide access to the ethmoidal mucosa. However, by medializing the middle turbinate, the width of the olfactory cleft is reduced. This may be a cause for persistent blockage and inflammatory disease of the olfactory cleft mucosa. A newer surgical concept is to keep the middle turbinate in a slightly lateralized position. This leads to a wider olfactory cleft with better ventilation and better access for topical steroids and probably less inflammation of the mucosa in the cleft. Care must be taken that the lateralization of the middle turbinate does not impair the frontoethmoidal and maxillary-ethmoidal drainage. Although the concept of a wider olfactory cleft due to lateralization of the middle turbinate suggests a good effect on olfactory function, it is not yet known whether it is superior to the traditional concept that focuses on wide access to the ethmoid by medializing the middle turbinate. Interestingly, the histologic analysis of these epithelia revealed numerous neuromas within the olfactory epithelium. One report also treated parosmia with selective resection of the olfactory bulb and a recent study rediscovered the technique used by Leopold to treat parosmia. Good long-term results (5 years), including restoration of the sense of smell, are seen after endoscopic sinus surgery. Slightly lateralized position of the middle turbinate leads to wide access of the olfactory cleft. Right nose: Wide view in the olfactory cleft due to lateralization of the middle turbinate. Note that the anterosuperior origin of the middle turbinate is not lateralized to keep the frontoethmoidal drainage open. Furthermore, the maxillary sinusotomy is lower than the inferior border of the middle turbinate to keep the maxillary sinus open. However, the study was conducted without a control group, which makes it difficult to distinguish such an effect from the spontaneous recovery rate. Although frequently mentioned as a therapeutic option, studies on zinc treatment for olfactory dysfunction have produced negative results. In postmenopausal women, estrogens have been reported to provide a certain protection against olfactory disturbances. However, recent studies indicate that estrogens are probably ineffective in the treatment of olfactory loss. Finally, although discussed frequently, the potential therapeutic use of orally administered vitamin A is questionable unless appropriate double-blinded studies become available. A different approach to the treatment of olfactory disorders is the detection and treatment of underlying causes. This approach may also involve the replacement of drugs suspected to have side effects affecting the sense of smell. If you give a systemic steroid treatment, the patient should undergo formal smell testing after the end of the treatment. The situation is similar for posttraumatic olfactory loss where efficient therapeutic options are lacking. However, smell training has recently been identified as a promising treatment option. In contrast, nostril closure in rats led to olfactory impairment and poor recovery rates. After 3 months both groups had improved olfactory function, but the group who completed smell training had a significantly better mean olfactory function. Due to this first promising study, it is now emphasized to ask patients to do smell training regularly. Numerous candidates for the pharmacological treatment of olfactory dysfunction have been proposed, without any clear benefit. Several studies estimate up to 5% of people to be anosmic without being aware of it. Testing olfactory function is preferable over simply asking the patient about smell function. Because one of the most frequent causes of olfactory disorders is sinonasal disease, endoscopy is highly likely to clarify any chronic sinonasal involvement. Sinonasal disease states can be treated, and consequently olfactory function will recover. It gives precious information about possible origin, further investigations to make, and possible prognosis. Principles of glomerular organization in the human olfactory bulb: implications for odor processing. Spatio-temporal dynamics of olfactory processing in the human brain: an event-related source imaging study. Chromatographic separation of odorants by the nose: retention times measured across in vivo olfactory mucosa. Intranasal trigeminal stimulation from odorous volatiles: psychometric responses from anosmic and normal humans. Taste, olfactory, and food texture processing in the brain, and the control of food intake. Chemosensory interaction: acquired olfactory impairment is associated with decreased taste function. Frequency and localization of the putative vomeronasal organ in humans in relation to age and gender. What is the estimated average percentage of anosmia within the general population Perceptual differences between chemical stimuli presented through the ortho- or retronasal route. Recovery of olfactory function following closed head injury or infections of the upper respiratory tract. The significance of post-traumatic amnesia as a risk factor in the development of olfactory dysfunction following head injury. Odour identification as a marker for postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a pilot study. Increasing olfactory bulb volume due to treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis-a longitudinal study. Complaints of olfactory disorders: epidemiology, assessment and clinical implications. Efficacy of systemic corticosteroid treatment for anosmia with nasal and paranasal sinus disease. It is therefore important that patients with persistent upper airway disease are evaluated for asthma by history, chest examination, and, if possible and when necessary, assessment of airflow obstruction before and after bronchodilation. It is important to not only assess whether patients have symptoms of lower airway disease but also to check whether those who know that they have asthma are well controlled.

Order 100mg voltaren overnight delivery

Transnasal endoscopic surgery is in accordance with the concept of minimally invasive surgery because it leaves anatomic structures intact and provides maximal control of the surgical target rheumatoid arthritis vitamin d buy voltaren 100mg fast delivery. The development of transnasal neuroendoscopy was made possible due to improvements in surgical technique, such as four-handed endonasal techniques,20 and dedicated surgical instrumentation. In fact, during the last decade, technological innovations have accompanied the evolution of the technique with corresponding improvements in its potential. Some of the major advances in instrumentation include rigid 45-degree endoscopes that are used in combination with double-angle instruments, and powered instruments such as intranasal drills, shavers, ultrasonic aspirators, and optic-cleaning systems that have reduced surgical times and allowed for the introduction of hydroscopy. Using such instrumentation, it is possible to access the entire ventral skull base, from the crista galli to the odontoid process. Lesions located intracranially can be reached through an inverted cone-shaped "tunnel," constituted by the nasosphenoidal tract. This avoids violation of the facial skeleton, both anteriorly and laterally, and, in selected cases, permits preservation of important vascular and nervous structures. For surgical approaches involving the cavernous sinus and the petrous apex, anatomic and surgical knowledge of the sphenoid sinus is fundamental as it should be considered the main avenue to access the cranial base via a transnasal route. Patient Selection/Indications Preoperative workup includes assessment of respiratory and cardio-circulatory function in addition to routine blood and urine tests. The former can be temporarily replaced with low molecular weight heparin (bridging therapy) and the latter substituted with paracetamol (acetaminophen) or codeine-based drugs. Patients should be informed about the risks associated with tumor excision, including vascular and neural injury, as well as of the possibility of duraplasty and the need to convert to an open procedure. The type of approach depends on tumor location, histologic type, and relation with major vessels. In general, transnasal neuroendoscopic surgery is indicated when it is favorable to approach the lesion in a mediolateral direction and when neurovascular structures are on the periphery of the lesion. Tumors with limited vascular supply and/or that compress and devascularize the cavernous sinus are most favorable for endoscopic resection. The possibility of a minimally invasive access for biopsy procedures is particularly advantageous for lesions that are amenable to nonsurgical treatment. A purely endoscopic approach is also contraindicated in cases in which neurovascular surgery (shunting)31,32 or orbital exenteration are needed. At the level of the petrous apex and the middle cranial fossa, it is extremely important to identify the relation between the lesion and adjacent arteries and veins (especially if aneurysm or thrombosis is suspected). Surgical Anatomy the cavernous sinuses are large venous spaces located laterally to the sphenoid body and interconnected by the intercavernous sinuses, almost forming a circular sinus (anterior coronary sinus, posterior and anterior to the foramen of Winslow). This is an osteofibrous conduit between the petrous apex and the petro-sphenoidal ligament of Gruber. The petrous apex is the portion of temporal bone located between the inner ear and the clivus. It may present with various degrees of pneumatization and varying quantities 630 Rhinology Table 47. The internal acoustic meatus divides it into an anterior compartment that is larger and more frequently involved by pathologic processes, and a posterior compartment that borders the semicircular canals. The petrous apex adjoins the temporal lobe and cerebellum, cranial nerves, and large blood vessels. The petrous sinuses run posteriorly and inferiorly to the posterior margin, which is in relation with dura mater that covers the anterior portion of the pontocerebellar angle. Inferiorly, it adjoins with the infratemporal fossa; medially, with the clivus; and laterally, with the otic capsule. A prerequisite of paramount importance in understanding this difficult anatomy is adequate experience in an anatomic laboratory, which can make the surgeon more familiar with the numerous anatomic variations. The main goal of cadaver dissection is to acquire a three-dimensional understanding of the anatomy to create a "patient-specific" navigation. In the live case, this experience leads the surgeon to safely identify anatomic landmarks and to select. After removal of the osseous posterosuperior wall of the sphenoid, the sellar and suprasellar content is evident. In this regard, the classic neurosurgical subdivision of the cavernous sinus walls into subunits based on the different surgical approaches (anteromedial triangle, paramedial triangle, Parkinson triangle, oculomotor trigone, anterolateral triangle, lateral triangle, posterolateral triangle, and posteromedial triangle) is not particularly helpful in a transnasal endoscopic approach. The tails of the turbinates guide the surgeon toward the natural ostium and allow localization of the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery (tail of the superior turbinate). These structures, which are the most important landmarks in surgery of the cavernous sinus and petrous apex, can be more or less evident depending on the extent of pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus. There are three basic patterns of sphenoid sinus pneumatization: sellar (complete pneumatization of the parasellar sphenoid with full exposure of the sellar bulge); presellar (partial pneumatization of the sphenoid but without extension to the sella); and conchal (nonpneumatized sphenoid). In the conchal variant, the lack of pneumatization makes it impossible to recognize the anatomic landmarks and thus requires special caution during surgical 631. After a wide right sphenoethmoidectomy with drilling of the pterygoid bone, the bony wall covering the lateral parasellar region was removed. The lateral (light blue) and medial (yellow) component of the cavernous sinus are highlighted with different colors. If the dura is preserved and only the bony component is removed, it is possible to observe the venous plexus connecting the two cavernous sinuses. Moving laterally, it is possible to observe the imprints of the third and fourth cranial nerves that are contained within the dural portion of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. Independent of the sphenoidal anatomy, the approach to lateral lesions of the cavernous sinus and petrous apex may also require creation of a surgical corridor via ethmoidectomy, partial excision of the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and opening of the pterygomaxillary fossa (transethmoidal-pterygoidal-sphenoidal approach). In a sellar or presellar sphenoid sinus, the first step is a complete removal of the anterior wall of the sphenoid. This leads to exposure of its floor, up to the lateral recess, and of its lateral bony wall, which has a quadrangular shape. In case of a conchal sphenoid, the absence of anatomic landmarks makes it necessary to identify them through careful dissection. Toward this purpose, the dissection should proceed, starting from the anterior margin of the floor of the sphenoid sinus, from medial to lateral, to identify the vidian foramen and the foramen rotundum. Following the protrusion of the lateral wall dorsally to the foramen, the lateral part of the cavernous sinus is reached. After a wide left ethmoidal-sphenoidotomy, important landmarks are evident on the posterior sphenoid wall as bony protrusions and depressions. Superolaterally, the interoptic-carotid recess and the protrusion of the optic canal and cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery are visible. Following the same route, it is also possible to reach the petroclival region, which, to be exposed, generally requires removal of part of the petrous bone. At this point, the bone of the petroclival region is removed until the underlying dura is exposed by 634 Rhinology. Endoscopic transnasal approach to the cavernous sinus versus transcranial route: anatomic study. The cavernous sinus and the middle cranial fossa represent the limits of superior and lateral dissection, respectively. During anatomic dissection, after completing the drilling of the clival bone and opening of the prepontine dura, one can observe the basilar artery, posterior cerebral arteries, and the superior cerebellar artery. In conclusion, the vidian canal is an important anatomic landmark: surgical access medial to it leads to the dura of the posterior fossa without encountering significant vascular or nervous structures. Medial and inferior to this point of access, the orbital apex can be accessed safely. After removal of the bony wall covering the medial and posterior cranial fossa and after exposure of the right cavernous sinus and opening of the posterior cranial fossa dura, it is possible to follow the sixth cranial nerve from its origin to its intracavernous portion. Surgical Technique As already mentioned, the approach to the sphenoid sinus and its complete exposure are the first steps in surgical treatment of the adjacent anatomic structures. The technique varies from a paraseptal to a transethmoidalpterygoidal approach depending on the lateral extent of the lesion. In all cases, it is advisable to fully expose the sinus by creating a single cavity that is fully open anteriorly. The extension of the lesion will also determine the route of access beyond the sphenoid. The techniques used for extra- or intradural dissection of a mass under endoscopy require that initial debulking has already been performed.

Buy 100mg voltaren otc

Finally arthritis pain vs fibromyalgia generic voltaren 50 mg overnight delivery, the incision is closed as described in open reduction and internal fixation. Naso-Orbito-Ethmoid Complex Fractures Most naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures are caused by highvelocity injuries associated with motor vehicle accidents, assaults, and sports activities. Note that the intercanthal distance is normally equivalent to the nasal base width and half the interpupillary distance. It then diverges to become the pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital orbicularis oculi muscle. It then splits to surround the lacrimal sac and inserts on the anterior and posterior lacrimal crest, as well as the frontal process of the maxilla. The bony horizontal buttresses of the naso-orbito-ethmoid complex are the superior and inferior orbital rims. The vertical buttresses are the frontal process of the maxilla and the frontal bone. The secondary buttresses (nasal septum, ethmoid, and lacrimal bones) provide little structural support. The key anatomic feature of naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures is disruption of the medial orbit. This ligament-bone complex has been termed the central fragment because it is central to both the diagnosis and surgical repair of these injuries. Diagnosis Physical Examination Injuries to the naso-orbito-ethmoid complex can be difficult to diagnose when there is significant facial swelling. Physical findings suggestive of a naso-orbito-ethmoid fracture include: (1) widening of the intercanthal distance greater than 30 to 35 mm; (2) narrowing of the palpebral fissure width; (3) widening of the nasal dorsum; and (4) rotation, deprojection, and shortening of the nose. Lack of support along the entire nasal dorsum is an indication that bone grafting will be necessary for reconstruction. The medial canthus/ eyelid can be grasped with forceps and gently lateralized to evaluate the stability of the medial canthal ligament insertion on the maxillary/lacrimal bones. A second technique involves insertion of a Boies elevator into the nose and bimanual palpation of the medial canthal insertion. Because the nasofrontal recess is just medial to the naso-orbito-ethmoid complex, the frontal sinus outflow tract must be carefully evaluated (see frontal sinus fractures). Characteristic naso-orbito-ethmoid fracture findings include: (1) disruption and widening of the nasal dorsum in the coronal plane; (2) a "Y-sign," occurring when the frontal process of the maxilla/lacrimal bone fractures is at the insertion of the canthal ligament, resulting in a Y-shaped bone fragment. The 3D reconstruction can be quite helpful to determine how many bone fragments are present in the fracture, and to give the patient/family a better understanding of the injury. Facial fractures peripheral to the naso-orbito-ethmoid complex (maxillary, zygomatic, and frontal sinus) are generally repaired first. This reconstitutes a stable scaffold upon which to base the naso-orbito-ethmoid repair. Although existing lacerations can provide helpful access points for the surgical repair, extended access is generally required for an accurate reduction. The standard surgical approaches used include: a coronal incision for access to the nasal root and application of bone grafts (see frontal sinus fractures treatment); transconjunctival incision(s) for access to the inferior orbital rim and medial orbital wall; and a sublabial incisions for access to the frontal process of the maxilla. Some surgeons prefer a subciliary eyelid incision instead of a transconjunctival incision, because it allows for more direct access to the medial orbital rim and frontal process of the maxilla. The authors prefer to avoid a subciliary eyelid incision to reduce the risk of postoperative ectropion, and to gain direct access to the medial orbit. Instead, the transconjunctival incision is combined with a limited (5 to 10 mm) lower eyelid incision in the "periorbital sulcus" over the frontal process of the maxilla. This limited exposure allows for application of hardware on the frontal process of the maxilla without the risk of ectropion. Incisions across the eyebrows and glabella ("open sky") result in unacceptable scarring/ paresthesias and should be avoided. If the central fragment is too small and/or unstable for internal fixation with miniplates, a transnasal wire should be used. Transnasal wires are applied via the coronal approach by drilling two holes in the central fragment: one above and one below the attachment of the medial canthal ligament. One end of a 28-gauge wire is then passed, from lateral to medial, through each of the holes. The free ends are then twisted down tightly onto the internal (nasal) surface of the central fragment. A 14-gauge needle (or wire passer) is then passed from the contralateral (uninjured) medial canthal region, behind the nasal bones, below the skull base, and exposing the needle tip on the injured side. It must also be passed posterior and superior to the lacrimal fossa to ensure the appropriate angle pull for an accurate reduction. Placement anterior to the lacrimal fossa will simply "splay" the canthal ligaments and result in postoperative telecanthus. Because the canthal ligament is intact, caution must be used to ensure that iatrogenic disruption does not occur. Location of the ligament can be determined by passing a 25-gauge needle through the skin just above the medial canthal complex. Subperiosteal elevation from the coronal incision will then expose the needle, alerting the surgeon to stop the dissection prior to reaching the medial canthal ligament. Exposure of the central fragment from above and below is continued until fracture reduction can be achieved. The plate is not placed spanning the central fragment because this exposure would likely result in iatrogenic detachment of the ligament from the central fragment. A second plate is generally applied inferiorly from the central fragment to the maxilla below, via the sublabial incision and the limited lower eyelid incision. Gross realignment of septal fractures should also be addressed in the acute setting whenever possible because this will improve support for the nasal dorsum and tip. The central fragment is then reduced with direct, cutaneous pressure on the medial canthal region. Finally, the wire is fixated to a miniscrew in the glabella region on the contralateral (uninjured) side. Over-reduction of the central fragment reduces the risk of postoperative telecanthus, and excessive narrowing of the intercanthal distance rarely if ever occurs. After closure of the incisions, nasal bolsters are applied to assist with redraping the medial canthal soft tissues. Each splint is wrapped in iodoform gauze to protect the underlying tissue from pressure necrosis. The bolsters are placed along the lateral nasal side wall and the first of two 14-gauge needles is passed through the holes in the bolster, through the fractured nasal bones just below the nasal root, and through a hole in the opposite bolster. A second needle is passed through the bolsters in a similar fashion, just below the nasal bones. The wires are twisted down simultaneously on each side, helping to redrape the soft tissues of the medial canthal region and lateral nasal sidewall. The wires should be twisted tight enough to apply gentle pressure to the overlying skin, but not result in necrosis. The skin underlying the bolsters should be checked on a daily basis to ensure adequate vascularity. Reconstitution of the medial canthal complex can be performed with one of two techniques: (1) bone graft reconstruction of the central fragment; or (2) use of a "canthal barb. The medial canthal ligament is then located by applying internal traction to the medial canthal soft tissue with forceps, and observing the cutaneous skin movement. The area that results in 1:1 motion of the skin with traction on the soft tissues is the medial canthal ligament. A 28-gauge wire suture is then passed through the internal medial canthal ligament remnant twice. The needle is removed and each end of the wire is passed through one of the holes in the bone graft. The free ends of the wire are twisted down tightly onto the internal (nasal) surface of the bone graft to secure the medial canthal ligament. The wire is pulled through the incision until the barb catches deep in the medial canthal ligament. The barb becomes buried in the soft tissue and provides excellent control of the medial canthal complex. After these steps have been completed, a 14-gauge needle is passed from the contralateral side, below the skull base, exposing the tip on the injured side.

Syndromes

- Learn how to take other medicines and when to eat

- Trembling or twitching

- KOH exam

- Poor appetite

- The average flow rate for females is 18 mL/sec.

- Electric shock

- Dehydration (from severe diarrhea)

- Include adequate fiber in your diet. Fiber is found in green leafy vegetables, fruit, beans, bran flakes, nuts, root vegetables, and whole-grain foods.

- Glaucoma

- Breathing problems

Buy cheap voltaren line

Infection occurs as a result of the interaction of the envelope proteins with specific receptors on the surface of the host cell (Sommerfelt arthritis in dogs meloxicam order cheapest voltaren, 1999). The production of new viruses does not directly result in host cell death, but rather the newly formed particles bud from the cell surface. The diseases associated with retroviral infections are usually a consequence of the site of retroviral insertion into the host genome, or as a result of alterations made to the types of cell they infect. To compress this number of genes into a small genome, the virus utilizes a number of strategies such as splicing and ribosomal frameshifting (Farabaugh, 1996). Packaging constraints on the amount of additional nucleic acid that can maintained within the viral genome mean that most vectors based on retroviruses are usually replication defective. Therefore, as we discussed for adenoviral vectors above, infective viral particles must be produced in specially constructed cell lines that can provide the necessary viral proteins. The recombinant viral shuttle vector is then transfected into a cell line that constitutively expresses the viral reverse transcriptase and capsid proteins. Viruses produced from this cell line can then be used to infect the target cells, where the vector will become integrated into the genome and the foreign gene expressed. The major advantages to using retroviral based vectors arise from the stability of the integration of the viral genome into the host. The disadvantages of such vectors are the random nature of the integration process, which may have deleterious effects on the host cell, and the general requirement that retroviruses have to infect only dividing cells. Therefore, much effort has been directed into making suitably safe lentivirus vectors (Zufferey et al. Some of the first experiments to identify transfected animal cells involved the complementation of a nutritional defect in a cell line. A number of other such metabolic markers have also been used to monitor the transfection process, but they all suffer from the requirement of a mutant cell line in order to detect transformed cells. This need has been overcome by using dominant selectable markers that confer a drug resistance phenotype to the transfected cells (Table 12. Antibiotics such as ampicillin have no effect on eukaryotic cells due to the lack of an animal cell wall. Some other antibiotics, particularly those that are protein synthesis inhibitors, are active against both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. At higher concentrations, aminoglycosides also inhibit protein synthesis in mammalian cells probably through non-specific binding to eukaryotic ribosomes and/or nucleic acids (Mingeot-Leclercq, Glupczynski and Tulkens, 1999). To achieve resistance as a method of selection, another gene encoded within the Tn5 transposon (producing neomycin phosphotransferase) is placed under the 12. We will discuss promoters used to drive expression of genes in animal cells in more detail below. The exposure of animal cells to high levels of toxic drugs for prolonged periods for the purposes of recombinant selection can give rise, at a very low frequency, to the formation of cells that have become spontaneously highly resistant to the drug. Mutations in this last class are particularly important for the high-level expression of foreign genes. This is then transfected into methotrexate-resistant cells and recombinants selected for in the presence of high levels of the drug. The insertion of a foreign gene into an animal cell is usually insufficient to direct its efficient expression and the production of the encoded protein. The foreign gene to be expressed must be associated with transcriptional and translational control elements appropriate for the cell type in which the protein will be produced. Most promoters used to drive the expression of foreign genes in animal cells are constitutive. We have previously discussed the Tet expression system for producing proteins in mammalian cells (Chapter 8). Many of the constitutive promoters used to drive gene expression in transfected cells are transcriptionally active in a wide range of cell types and tissues, but most exhibit some degree of tissue specificity. In addition to a suitable promoter, genes to be expressed in animal cells also require a polyadenylation site, a transcriptional termination signal and a variety of translational control elements. Immediately after the sperm enters the egg, the fertilized Analysis of Genes and Genomes Richard J. The maternal and paternal pronuclei then fuse with each other to form a single fertilized nucleus. At this stage, the zygote is called a blastocyst and the cavity is called the blastocoele. The cavity divides the cells of the blastocyst into an inner cell mass (which will become the embryo) and an outer trophoblast (which will form the placenta). Before implanting into the wall of the uterus, the blastocyst floats in the uterine cavity for 2 days and sheds the zona pellucida, allowing its adherence to the uterine wall. Not all of the newly divided cells will go on to form parts of the animal; some are programmed to die as part of the normal developmental process (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977). The mouse has long been the organism of choice for this type of manipulation as a laboratory mammal that has relatively well understood and amenable genetics. The production of altered mouse embryos for the creation of transgenic mice is certainly well advanced but other animals, particularly farm animals, have also been modified using similar techniques. Immediately following fertilization, the large male and small female pronuclei are visible under the microscope as discrete entities. The injected embryos are cultured in vitro until the morula stage and then implanted into a pseudo-pregnant female mouse that has been previously mated with a vasectomized male. The stimulus of mating elicits the appropriate hormonal changes needed to make her uterus receptive. Mating two of the heterozygotes can produce homozygous mice, with one in four of their offspring being homozygous for the transgene. Assuming that the transgene integrated before the first cell division, the pups should be heterozygous for the transgene. Inbreeding of the heterozygotes will generate homozygous individuals rat growth hormone was microinjected into the pronuclei of fertilized mouse eggs (Palmiter et al. Of 21 mice that developed from the injected eggs, seven carried the fusion gene and six of these grew significantly larger than their littermates. At 74 days of age, the transgenic mice weighed up to 44 g, while their non-transgenic littermates weighed approximately 29 g. The technique has also been used to attempt to produce therapeutic proteins within transgenic animals. It cannot be used to delete genes (knock-out), or to alter existing genes within the genome. The randomness of the insertion can have dramatic effects on the expression of the foreign gene depending on the precise site of the insertion within individual animals. That is, the offspring of highly expressing parent animals may show considerably different levels of expression. In some cases, this may be due to altered genomic methylation patterns at the site of the transgene (Palmiter, Chen and Brinster, 1982). The production of transgenic mice by pronuclear injection can occasionally result in a mosaic animal, where the transgene is only present in a limited set of tissues and organs of the animal. This happens when integration of the transgene is delayed until after the first cell division. They can be cultured in vitro by growing them in a dish coated with mouse embryonic skin cells that have been treated so they will not divide. Unlike most other animal cells, they can be maintained in culture, through successive cell divisions, for long periods. The blastocyst is then implanted into the uterus of a pseudopregnant female and pups produced. The chimeric pups are then crossed with wild-type animals to generate true heterozygotes, which can then subsequently be inbred to create a homozygote. This means that targeted transgenes can be produced in which specific genes of the genome are either deleted or altered (Thomas and Capecchi, 1987). Cells containing the tk gene may be killed by treatment with ganciclovir, which is phosphorylated by thymidine kinase, and then undergoes further phosphorylation by cellular kinases. If, however, homologous integration has occurred, then the tk gene will be lost and cells will survive ganciclovir treatment (Mansour, Thomas and Capecchi, 1988). In addition to supplying a mechanism to delete genes (knock-out), specific genes may also be replaced with mutated versions of themselves. The ability to specifically knock out genes can provide an immensely powerful approach to assigning gene function in whole animals, especially the mouse (Osada and Maeda, 1998).

Buy generic voltaren 50mg on-line

A second arthritis pain hips symptoms generic 50 mg voltaren, labelled, antibody (the secondary antibody) is then used to detect the presence of the first antibody. This has several advantages; firstly, the multivalent nature of antibody binding means that a substantial increase in sensitivity is achieved, and secondly, a single secondary antibody can be used to detect a number of different primary antibodies. The isolation of nuclear material from cells is a relatively straightforward process. The primary antibody will specifically bind to the antigen to which it was raised. A labelled secondary antibody is then added to detect the location of the primary antibody. The secondary antibody is often labelled with an enzyme whose activity, in the presence of appropriate substrates, results in either a colour change on the membrane or the emission of light that can be detected using X-ray film the cell wall will result in the nuclear material spilling out from the broken cells. The method used for the lysis procedure depends upon the nature of the host cell itself. For instance, bacterial cells are often treated with the enzyme lysozyme to weaken their cell wall before being lysed with detergents. The remaining soluble material will then be vortexed in the presence of phenol to remove proteins by denaturing then. Chloroform is often used in conjunction with phenol (as a phenol/chloroform solution) since it is also a protein denaturant, but it also stabilizes the rather unstable boundary between the aqueous phase and a pure phenol layer. The nucleic acid remaining in the aqueous layer can then be precipitated using ethanol. Insufficient cell lysis will result in low plasmid yields, while cells that have been lysed too much suffer similar problems. This method, termed the alkaline lysis procedure, takes advantage of the fact that at alkali pH (between 12. Under these conditions, other contaminants will not bind to the matrix and can be washed away. It is part of the normal flora of the human mouth and gut, helping to protect the intestinal tract from bacterial infection, aiding digestion and producing small amounts of vitamins B12 and K. The bacterium, which is also found in soil and water, is widely used in laboratory research and is probably the most thoroughly studied life form. A cut-away model of the bacterium showing some of the cellular layers and components, and E. As far back as the mid-1940s it was known that bacterial cells were able to exchange genetic material with each other in a semisexual manner. The experiments of Lederberg and Tatum clearly demonstrated the transfer of genetic information through bacterial conjugation (Lederberg and Tatum, 1946). The ability to perform this transfer is conferred by a set of genes called F (for fertility). When conjugation occurs, the F genes start travelling across the pilus, dragging the rest of the genome behind them. The bacterial genome can be measured, in minutes, from the origin of transfer with the amount of time it takes for a particular gene to be transferred from one bacterium to another indicating how far it is from the origin of replication. However, the size of the F episome precludes easy analysis and manipulation and its gene transfer properties can make it unstable. Most commonly used vectors are based either upon plasmids or bacteriophage lambda (). In general, vectors can be thought of as a series of discrete modules that provide requirements essential for efficient molecular cloning. A huge array of different types of vector is available today, with many being highly specialized and designed to perform a specific function. In this chapter, I will discuss some of the general points of vector design, but will concentrate on vectors that are commonly used in cloning experiments (Table 3. Plasmids are widely distributed throughout prokaryotes and range in size from approximately 1500 bp to over 300 kbp. The replication of the plasmid is often coupled to that of the host cell in which it is maintained, with plasmid replication occurring at the same time as the host genome is replicated. Plasmids are often described as being either relaxed or stringent on the basis of the number of copies of the plasmid that are maintained within the cell. At least part of the basis of this difference is the different mechanisms employed by plasmids in order to replicate themselves. In general, relaxed plasmids replicate using host derived proteins, while stringent plasmids encode protein factors that are necessary for their own replication. Other gene names reflect biological function, for example, Hbb for the haemoglobin -chain, and Adh for alcohol dehydrogenase enzymatic activity. The assignment of chromosomal locations for genes of unknown function developed soon after the establishment of successful metaphase spreads, chromosome banding methodologies, somatic cell hybrids, isozyme separation and the ability to associate genes and phenotypes with a particular site on the chromosome. It has also become common to use the same name for the gene as for the enzyme or other protein that it encodes. Often, the gene name is italicized whereas the gene product is not to distinguish between the two. This can, however, be a source of confusion, since there is not necessarily a one-to-one relationship between the two entities. Additionally, nomenclature used for one organism or species may be different in another. Traditionally, recombinant plasmids tend to bear the initials of their creator(s) followed by a number that may indicate the numerical order in which the plasmids were produced, or perhaps has some deeper meaning. Although many attempts have been made to standardize nomenclature (White, Mattais and Nebert, 1998), historical names tend to be maintained. Most plasmids in common use today are based upon the replication origin of the naturally occurring E. Colicin E1 is a transmembrane protein that causes lethal membrane depolarization in bacteria (Konisky and Tokuda, 1979). The drug resistance gene codes for a protein that interferes with the action of colicin by inhibiting its ability to form a channel through the bacterial membrane (Zhang and Cramer, 1993). Bacteria harbouring the ColE1 plasmid can be distinguished from their counterparts that do not possess the plasmid by their ability to grow on plates containing colicin E1. Unlike the bacterial origin of replication (OriC), however, the replication of ColE1 proceeds in one direction only. It codes for, amongst other things, the bacteriocin colicin E1 (the product of the cea gene) and an immunity protein (the product of the imm gene) that prevents the toxic effects of the bacteriocin in cells harbouring the plasmid. The relative positions of these replication control elements to the origin (ori) are shown. This is important for cloning experiments when a mixed population of plasmids, which is often the result of a ligation reaction, is transformed into bacteria. Individual transformants produced in this way will contain a single plasmid and not a mixed population. What was required was a plasmid that could be replicated in the same way as ColE1, but in which recombinants could be easily recognized. This plasmid contains the ColE1 origin of replication (ori and rop), together with two antibiotic resistance genes. Transformed cells are first grown on bacterial plates containing ampicillin to kill all the cells that do not contain a plasmid. Those cells that grow on ampicillin are then replica plated onto medium containing both ampicillin and tetracycline. Embedded within the coding sequence of lac Z are the recognition sites for a number of restriction enzymes. Certain mutations in the 5 region of lacZ prevent subunit association of the resultant protein (-peptide) and the monomers lack enzyme activity (Ullmann, 1992). In some such mutants, subunit assembly (and enzyme activity) can be restored by the presence of a small (50- or so amino-acid) amino-terminal fragment of the lacZ product (the -polypeptide) (Juers et al.

50mg voltaren for sale

Although some sympathetic fibers reach the nasal cavity via the nasociliary nerve how is arthritis in back diagnosed purchase voltaren 100 mg without prescription, the main autonomic pathway is through the pterygopalatine ganglion and its branches. Most of the parasympathetic fibers are derived from the facial nerve originating from the superior salivary the pterygopalatine fossa is a space located lateral to the nasal cavity and posterior to the maxillary sinus. It is situated medial to the infratemporal fossa and anteroinferior to the middle cranial fossa. It houses various vascular and neural structures and serves as a conduit to adjacent structures via multiple fissures, canals, and foramina. In the medial wall lies the previously mentioned sphenopalatine foramen, which connects to the nasal cavity and contains the sphenopalatine artery and nerve. The inferior orbital fissure in the anterior wall of the "box" connects the pterygopalatine fossa to the orbit and contains the infraorbital artery and nerve. Inferiorly, the pterygopalatine fossa continues into the pterygopalatine canal, which connects to the roof of the oral cavity. This canal contains the descending palatine artery and 16 1 Nasal and Paranasal Sinus Anatomy and Embryology I Basic Science and Patient Assessment nerve and eventually leads to the greater and lesser palatine foramina. Lastly, through the lateral wall of the "box," the pterygopalatine fossa communicates with the infratemporal fossa through the pterygomaxillary fissure. The Paranasal Sinuses There are four paired sinus cavities that arise and pneumatize at different times during development. The ethmoid sinuses are further divided into anterior and posterior sinuses by the basal lamella of the middle turbinate. The center piece of the "box" is the ethmoid complex, with which all other sinuses border and are intimately related. Development of the paranasal sinuses varies from individual to individual and can be affected by disease states. For example, patients with cystic fibrosis often have underdeveloped paranasal sinuses in comparison to ageand gender-matched controls. Another theory regarding the role of the sinuses in evolutionary development is that the pneumatization of the facial skeleton made the head lighter, allowing human. Note the star-shaped pattern of mucociliary clearance emanating from the floor of the maxillary sinus against gravity to the natural ostial region. Note the left posterior sphenoethmoid cell pneumatizing posteriorly into the face of the left sphenoid sinus (red oval). Note the soft tissue swelling consistent with chronic rhinosinusitis in the right anterior ethmoid. Furthermore, the sinuses may have aided the development of verbal communication by serving as the resonance chamber of the human voice, much like the hollow cavity of a string instrument. Note Patients with cystic fibrosis often have underdeveloped paranasal sinuses in comparison to age- and gender-matched controls. It is thought to originate from the anterior ethmoid sinuses in 88% of cases and from the posterior ethmoid in 12% of cases. The corresponding nerves, as well as the greater palatine nerve, provide the innervation to the sinus. Venous drainage is performed by the facial vein anteriorly and the maxillary vein posteriorly. Each maxillary sinus is a space within the maxilla, shaped like a pyramid on its side. The base of the pyramid is along the lateral nasal wall, and the apex is pointing laterally toward the zygoma. The sinus is bounded anteriorly by the soft tissue of the face, posteriorly by the infratemporal fossa, superiorly by the orbital floor, inferiorly by the alveolar surface of the maxilla, and medially by the lateral nasal wall. The maxilla bone itself articulates with eight different bones: frontal, ethmoid, palatine, nasal, zygomatic, lacrimal, inferior turbinate, and vomer. The ostium of the maxillary sinus opens into the posteroinferior half of the ethmoid infundibulum in a crevice created by the uncinate process of the ethmoid. The mucus generated within the maxillary sinus is mobilized by the cilia against gravity, up from the sinus floor toward the maxillary sinus ostia in a stellate pattern. The uncinate process of the ethmoid bone forms a significant portion of the medial antral wall within the middle meatus. This is reported to be associated with episodes of recurring acute rhinosinusitis. Sphenoid Sinuses Note the cause of perforations in the bony medial wall of maxillary sinuses is not known, but they can result in naturally recurring recirculation of mucus back into the maxillary sinus. Another anatomical variation is the infraorbital ethmoid cell (Haller cell), which is an ethmoid cell that pneumatizes into the roof of the maxillary sinus/floor of the orbit the sphenoid sinuses are centrally located in the skull base and are intimately related to the sella turcica posteriorly, cavernous sinuses and internal carotid arteries laterally, and optic nerves superiorly. Also, the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and the vidian nerve neighbor the sinus. The sphenoid sinus drains through the sphenoethmoid recess, which is located in the space between the superior turbinate, septum, and skull base. The sphenoid bone, which is located at the most posterior portion of the nasal cavity, articulates with the ethmoid, frontal, vomer, occipital, parietal, temporal, zygomatic, and palatine bones. The sphenoid sinus does not begin its pneumatization process until the third year of life, and the pneumatization pattern varies greatly, ranging from being limited to the sphenoid bone itself to extending into the greater wing of the sphenoid, the pterygoid process, and even the occipital bone. Pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus is classified into four categories: conchal, presellar, sellar, and postsellar, each type comprising 4. The intersinus septum may lie obliquely, anchoring itself to the internal carotid artery or the optic nerve, as seen in. Separate from the intersinus septum that divides the left from the right sphenoid are occasional incomplete septations, which are commonly inserted onto the carotid artery. Note the space lateral to the dotted red line drawn from the foramen rotundum to the canal of the vidian represents the pterygoid recess of the sphenoid sinus (orange). Note the relative position of the mastoid air cells (yellow) and petrous apex with cochlea (red circle). Occasionally, the anterior clinoid process itself can be pneumatized, forming a recess within the sphenoid sinus. Again, this is of clinical importance in the management of lateral sphenoid sinus encephaloceles associated with Sternberg canal. The posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus is part of the clivus (Latin for "slope"), which is an anatomical region comprised of the sphenoid and occipital bones extending from the foramen magnum to the posterior boundary of the sella turcica called the dorsum sellae. A chordoma, a tumor that is thought to arise from the cellular remnants of a notochord, is the most common tumor of the clivus. Note A chordoma, a tumor that is thought to arise from the cellular remnants of a notochord, is the most common tumor of the clivus. Note the intersinus septum of the sphenoid sinus may lie obliquely, anchoring itself to the internal carotid artery or the optic nerve. A highly pneumatized posterior ethmoid cell occasionally extends posteriorly and "invades" the superior, lateral, and posterior portions of the sphenoid bone. Note the saddle-shaped depression of the sella turcica between the posterior planum sphenoidale and the clivus. The sphenoethmoid cell may pneumatize to a variable extent around the optic nerve, which can be manifested simply as a lateral bulge, or in extreme cases, appear to cross through the center of the cell. It has been noted that genetic factors may also play a role, as sphenoethmoid cells appear to be more common in Asian patients. It articulates with the ethmoid, lacrimal, maxillary, nasal, parietal, sphenoid, and zygomatic bones. The drainage passageway of the frontal sinus is an hourglass-shaped area composed of three different components. The top portion of the hourglass is the frontal infundibulum, which is the inferiormost aspect of the frontal sinus. The narrow portion of the hourglass is the frontal sinus ostium that sits in the posteromedial part of the sinus at the inferior end of the frontal infundibulum. The inferior portion of the hourglass is the frontal recess, a narrow cleft within the anterior ethmoid complex that is akin to an upside-down funnel. Mucus generated within the frontal sinus circulates around the sinus in a superolateral-to-inferomedial direction before draining out through the frontal recess17. Narrowing in any of these structures or disease within the anterior ethmoid sinus can result in frontal sinusitis. Anatomical variations are common in the frontal sinus and have been discussed in great detail elsewhere. Several ifferent classification systems are available for these, but none is widely agreed upon.

Buy voltaren amex