Purchase cheap diabecon online

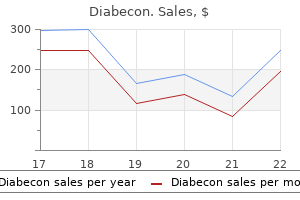

This device is not yet available commercially but will make cardiac wounds easier to manage in the Emergency Department diabetes insipidus newborn 60caps diabecon free shipping. Immediately transport the patient to the Operating Room for definitive repair of the cardiac wound and any other injuries by a Trauma or Cardiovascular Surgeon. Foley catheters can become dislodged and restart troublesome bleeding if pulled too tightly. The components include the silicone suction cup (O), flexible shaft, and low-profile collapsible blood flow locking membrane. A drop in cardiac output can result if the cuff obstructs the cardiac valves, impinges on the chordae tendineae, or occupies too much space within the cardiac chamber. The suture should be tied just tight enough to stop the bleeding and not necessarily achieve complete hemostasis. Care should be exercised to avoid ligation of the major coronary vessels and their branches. Dysrhythmias can result from occlusion of venous inflow (Sauerbruch maneuver) or injury to the coronary vasculature. If the patient is resuscitated, administer broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent any potential infectious complication. The great vessels also include the vena cava, aorta, innominate artery, subclavian artery, and subclavian vein. The mortality from injuries to the subclavian artery is approximately 5% if patients who are moribund on admission to the Emergency Department are excluded. In these cases, an Emergency Department thoracotomy may be performed for hypovolemic shock. The role of the Emergency Physician is to rapidly and temporarily control bleeding and ensure the transport of the patient to the Operating Room for definitive repair. The Emergency Physician must be versed in the techniques used to repair cardiac wounds and resuscitate the patient if there is a delay in transporting the patient to the Operating Room. Crush injuries, deceleration injuries, motor vehicle versus pedestrian collisions, and penetrating thoracic injuries may all signify an injury to a thoracic great vessel. The vessels that are most commonly injured include the aorta, innominate artery, pulmonary vein, and venae cavae. The portable anteroposterior chest radiograph is the initial radiographic screening. It may reveal loss of the aortic knob contour, left-sided pleural effusions, mediastinal widening, nasogastric tube deviation, or tracheal deviation, all of which suggest injury to a great vessel. Other findings suggestive of great vessel injury include depression of the left mainstem bronchus, left apical capping, narrowing of the carinal angle, sternal fractures, opacification of the aortopulmonary window, and widening of the paraspinous stripe. Numerous physical examination findings are suggestive of a thoracic great vessel injury. Asymmetric pulses or unequal blood pressures between the extremities are quick and simple to evaluate. Steering wheel contusions, sternal fractures, thoracic spine fractures, and a left-sided flail chest signify potential intrathoracic injury. A thoracic outlet hematoma or a hoarse voice can occur from injury to the aorta or one of its major branches. Bernardin B, Troquet J-M: Initial management and resuscitation of severe chest trauma. Refer to Chapter 54 for a discussion in which a thoracotomy is contraindicated, as any hilum or great vessel repair is also contraindicated. A pericardial tamponade or cardiac injury may require management prior to managing Reichman Section3 p0301-p0474. Unfortunately, the fingertip interferes with visualization of the wound and places the Emergency Physician at risk for a needlestick injury. Digital pressure and rapid transport to the Operating Room is the most practical method of dealing with injuries to the subclavian vessels. These vessels are extremely difficult to control through a traditional anterolateral thoracotomy incision. If digital pressure is ineffective, pack the apex of the thoracic cavity with laparotomy pads or gauze squares and apply compression from below. Inflate the cuff of the Foley catheter with sterile saline to check its integrity and look for leaks. Open the hemostat, inflate the cuff with 5 to 10 mL of sterile saline, and reclamp the Foley catheter. This step should be completed quickly to prevent air from being drawn through the catheter. The cuff is inflated and gentle traction (arrow) is applied to occlude the wound with the cuff. This will provide temporary hemostasis until definitive repair in the Operating Room. Injuries to the pulmonary vasculature in the region of the hilum are most expeditiously controlled by placing an atraumatic vascular clamp across the respective hilum. These patients should be immediately transported to the Operating Room to be placed on bypass and repair the injuries. It is not recommended for the Emergency Physician to suture great vessel injuries in an attempt to repair them. Immediately transport the patient to the Operating Room for definitive repair of the great vessel injury and any other injuries by a Trauma or Cardiovascular Surgeon. A Satinsky vascular clamp may be used to partially occlude the great vessel and isolate the injury. Providing complete hemostasis can result in excessive traction on the catheter causing the cuff to pull through the wound. It does not interfere with visualization of the wound or the simultaneous performance of cardiac massage. Inaccurate digital control can lead to unnecessary loss of blood during transport of the patient to the Operating Room. Foley catheters, if pulled too tightly, can become dislodged and restart troublesome bleeding. An overly rough mobilization and clamping can increase the size of the injury and cause massive bleeding. Cross-clamping of the aorta and/or pulmonary artery will obstruct peripheral blood flow. The vessel must be repaired or the patient placed on bypass to prevent anoxia and permanent neurologic dysfunction. The survival of the patient depends on their presenting condition as well as the speed and accuracy with which the intrathoracic hemorrhage is controlled. It arches to the left and backward at the level of the sternal angle to become the aortic arch. The arch gives rise to the brachiocephalic trunk, left common carotid artery, and left subclavian artery. The aortic arch is directed inferiorly after giving rise to the left subclavian artery and is known as the descending aorta. The descending aorta is subdivided into the thoracic portion above the diaphragm and the abdominal portion below the diaphragm. It descends through the posterior mediastinum, lying first against the left side of the fifth thoracic vertebral body. As it descends, it gradually approaches the midline of the 12th thoracic vertebral body, at which point it passes through the diaphragm. It travels forward, away from the vertebral bodies, and to the right at the level of the ninth thoracic vertebral body. It lies posterior and medial to the descending thoracic aorta throughout most of its course. Anatomy of the aorta and surrounding structures of the mediastinum and left hemithorax. These patients should have the appropriate indications to perform an anterolateral thoracotomy (Chapter 54). The thoracic aorta may also be occluded immediately prior to laparotomy if the patient has a tense abdomen filled with blood. The abdominal incision will decompress the abdomen and result in hypotension, decreased coronary and cerebral perfusion pressure, exsanguination, and death. Uncontrollable hemorrhage anywhere below the diaphragm can be controlled by temporarily occluding the descending thoracic aorta.

Quality 60 caps diabecon

Bone will appear hyperechoic and easily differentiated from muscle and subcutaneous tissue definition of gestational diabetes mellitus generic diabecon 60 caps otc. The needle can be inserted with or without ultrasound guidance once the landmarks are identified. This helps avoids any sudden and painful movements of the needle within the joint cavity. Gently aspirate synovial fluid to confirm the proper needle position within the joint cavity. If bone is encountered, slightly withdraw the needle and advance it in a different direction. The patient is prepared by draping the lateral joint where the needle will be inserted (A) or by dressing the area with a sterile clear dressing (B). Note the "seagull sign," which is a V-shaped hypoechoic area surrounded by hyperechoic bone. Advance the needle to a depth of 1 to 2 cm and aspirate until synovial fluid is obtained. Ultrasound transducer placement: Start with transducer placement longitudinally and lateral or medial to the patella for a first view of the possible fluid collection. Remarks: the blind lateral and medial parapatellar approaches are used with high relative success. This is most likely due to the large joint space and minimal accessory structures. Pooled studies demonstrate an overall lower success rate with the blind medial midpatellar approach (64%) compared with the blind superior lateral patellar approach (87%). Some studies suggest that 150 to 180 mL may be necessary for ruling out joint capsule involvement. The knee may allow for 30 mL or more, whereas the finger may accommodate only 1 mL of fluid. Often, it is only necessary to inject a minimal amount of dye before extravasation is seen. If the joint capsule is ruptured, a greater amount of fluid can be injected, as it will escape through the breach. There is often visible swelling of the skin around the injected joint if there is no breach. The relatively thin dermal and subcuticular layers over the phalanges often make one wonder about deep soft tissue avulsions or lacerations and the potential involvement of the joint capsule. Injection with methylene blue is an ideal method to assess joint capsule integrity. The success rate of arthrocentesis is much lower in the phalangeal joints than larger joints. The overlying ligaments and tendons are more prominent and the synovial capsule is smaller. A failure rate of 15% for finger arthrocentesis was found among skilled surgeons and as high as 32% among first-year residents. Remarks: the application of distal traction often causes a depression to appear on both sides of the extensor tendon. The concern for joint capsule rupture without the concomitant need for operative exploration and fixation is rare in joints other than the knee and fingers. The knee is relatively easy to inject while the fingers and toes are more difficult. Arthrocentesis with methylene blue injection in the knee and finger is discussed below. Extravasation of methylene blue through the injury site is indicative of a ruptured joint capsule. These require exploration, high-volume irrigation, and adjunctive medical treatment. Although some wounds can be closed primarily in the Emergency Department after consultation with an Reichman Section06 p0775-p0970. A minimal amount of methylene blue needs to be injected before visible extravasation will occur. Aspiration of blue fluid provides additional confirmation of intracapsular needle placement. Maintain a high index of suspicion for a joint capsule rupture in the face of a negative study given the significant rate of ectopic needle placements. Methylene blue injections may not be sensitive enough to identify violation of the joint capsule and may lead to an unacceptable rate of false negatives in the setting of puncture or stab wounds. The patient may already be receiving opioid analgesics in the setting of a significant traumatic injury. Warn the patient or their representative that urine excretion of methylene blue can change the color of their urine. A hemarthrosis may be insidious, appear with progressive swelling and pain with joint motion, and often without joint warmth. Tendon and cartilage damage may not be apparent for some time and may present with joint stiffness or arthritis. Septic arthritis is the most concerning complication, evidenced by swelling, erythema, warmth, pain with range of motion, and systemic symptoms. Cellulitis may also complicate the procedure and appear with local warmth, erythema, and induration over the site. Refer to Chapter 97 for a more complete discussion regarding the complications of arthrocentesis. The postprocedural care consists of monitoring for external bleeding and swelling. This procedure can help to determine between repairing a wound and sending the patient home or admitting a patient to the hospital for joint exploration and closure. Stradling B, Aranha G, Gabram S: Adverse skin lesions after methylene blue injections for sentinel lymph node localization. Pichler W, Grechenig W, Grechenig S, et al: Frequency of successful intraarticular puncture of finger joints: influence of puncture position and physician experience. Metzger P, Carney J, Kuhn K, et al: Sensitivity of the saline load test with and without methylene blue dye in the diagnosis of artificial traumatic knee arthrotomies. Forces that cause injury can be large enough to result in fractures, displaced fractures, and joint dislocations. While each injury is different, some general principles can be applied to all displaced fractures and joint dislocations. Specific instructions on the techniques to reduce common fractures and dislocations are in Chapters 101 through 113. The direction of fracture displacement is influenced by muscle contraction following the injury. Humeral shaft fracture between the insertions of the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles. A fall forward on an outstretched arm is the most common mechanism of injury of the upper extremity. It results in elbow dislocations occurring most frequently in a posterior direction. Distal radius fractures occur most often as Colles fractures, and supracondylar fractures are extension-type fractures in 95% of cases. No joint benefits from a prolonged dislocation as damage to articular cartilage increases with time. Reduction should occur on an emergent basis when perfusion to the extremity is absent. The earlier perfusion is restored, the better is the chance of avoiding tissue necrosis. Note the presence of an expanding hematoma, absent distal pulses, or delayed capillary refill. Orthopedic injuries more commonly associated with vascular injury include knee dislocations, posterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations, and supracondylar fractures. The importance of early reduction and repair of vascular injuries is emphasized in knee dislocations.

Generic 60 caps diabecon visa

Connecting the handheld manometer (A) or mercury manometer (B) to the gastric aspiration port newcastle diabetes symptoms questionnaire cheap diabecon 60caps on-line. Inflate the esophageal balloon to a pressure of 25 mmHg if bleeding continues through the gastric aspiration port or the nasogastric tube. If bleeding continues to persist, increase the esophageal balloon pressure in 5 mmHg increments until 45 mmHg is achieved or the bleeding stops. The gastric balloon is inflated with 50 to 100 mL increments of air to a volume of 250 to 300 mL. Fill the gastric balloon with more air gradually up to a total volume of 300 mL of air. The only difference is that it only has the esophageal balloon and inflation port. Deflate the esophageal balloon for 5 minutes every 6 hours to avoid esophageal pressure necrosis. Oral medications, if required, may be administered through the gastric aspiration port. Monitor the patient continuously for signs of chest pain, respiratory distress, and aspiration. Migration of the esophageal balloon into the hypopharynx of an awake patient will result in respiratory distress. The esophageal balloon should not remain inflated for more than 24 hours to avoid mucosal necrosis. If there is no bleeding after 24 hours, deflate the esophageal balloon and leave the gastric balloon inflated for an additional 24 hours. If variceal hemorrhage recurs, reinflate the appropriate balloons while alternative therapy to control bleeding is sought. Control of esophageal variceal bleeding can be achieved by balloon tamponade in 50% to 94% of patients. A video laryngoscope can be used to place the tube into the esophagus and not the trachea. Periodic deflation of the esophageal balloon every 6 hours will help prevent this. These can be prevented by adhering to proper balloon inflation techniques with pressure monitoring. Cardiac arrhythmias and pulmonary edema can occur and require continuous monitoring in the setting of an Intensive Care Unit. The patient may become agitated from the discomfort of the tube, migration of the tube into the hypopharynx resulting in hypoxemia and asphyxiation, or as chest and back pain is experienced from a misplaced or overdistended balloon. Excessive traction on the tube can result in epistaxis or pressure necrosis of the lips, nose, or tongue. Liquid in the balloons causes them to be heavy, increases the risk of pressure necrosis, and makes them hard to deflate. Only 25% of patients with ascites, jaundice, and encephalopathy achieve lasting hemostasis with balloon tamponade. Khaliq A, Dutta U, Kochhar R, et al: Pressure necrosis of ala nasi by Sengstaken-Blackmore tube. Teres J, Planas R, Panes J, et al: Vasopressin/nitroglycerin infusion vs esophageal tamponade in the treatment of acute variceal bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices: Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices: a prospective multicenter study. Angelico M, Carli L, Piat C, et al: Isosorbide-5-mononitrate versus propranolol in the prevention of the first bleeding in cirrhosis. Kashiwagi H, Shikano S, Yamamoto O, et al: Technique for positioning the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube as comfortably as possible. Rosat A, Martin E: Tracheal rupture after misplacement of SengstakenBlakemore tube. Fogg T, Court L, Reid C: Critical care transport following balloon tamponade of variceal haemorrhage. Panes J, Teres J, Bosch J, et al: Efficacy of balloon tamponade in treatment of bleeding gastric and esophageal varices: results in 151 consecutive episodes. Indications for enteral feeding tube placement include prolonged neurogenic or mechanical dysphagia, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and poor intake. Relatively common complications related to enterostomy tubes encountered in the Emergency Department include tube dislodgement, tube occlusion, leakage around the tube, and skin changes. Emergency Physicians fill a valuable role in solving G-tube problems as many Reichman Section5 p0657-p0774. This article reviews the methods and materials used in gastrostomies and the approaches to replacing displaced or malfunctioning G-tubes. Each of the techniques attempts to create a leakproof interface between the stomach, the feeding tube, and the anterior abdominal wall. All three techniques involve suturing the stomach wall to the undersurface of the abdominal wall. The stomach wall remains attached to the abdominal wall, and chance of intraperitoneal contamination is decreased if a surgically placed G-tube is accidentally dislodged in the early postoperative period. Modern endoscopic techniques have provided a less invasive option for the placement of percutaneous feeding tubes. Popular endoscopic techniques in use today require two persons- an Endoscopist and an operator at skin level. The Endoscopist then visualizes the light of the endoscope as it transilluminates the abdominal wall. The guidewire is secured around a G-tube and pulled retrograde from the mouth to the exit site on the anterior abdominal wall. Regardless of which technique is used to establish the gastrostomy, the stomach is not sutured to the abdominal wall. A fibrous tract eventually forms between the anterior abdominal wall and the stomach. Administration of the nutrients directly into the jejunum through a percutaneously placed jejunostomy tube is recommended to bypass the stomach and decrease the risk for aspiration. The anterior abdominal wall is pierced with a cannula or needle under endoscopic guidance. A suture or guidewire is then introduced into the gastric lumen and grasped with a snare. A basic understanding of G-tubes is all that is needed to diagnose and treat most problems. Familiarity with the characteristics of G-tubes is helpful in assessing tube function and determining appropriate replacements. Standard de Pezzer and mushroom catheters modified with rings or bolsters may require endoscopy for removal. Contact the provider who inserted the tube to determine if removal can be completed safely in the Emergency Department when in doubt. The visible portion of the G-tube outside the skin may or may not indicate what type of internal stabilization exists. The essential features of the G-tube include the tube, an internal bolster, an external fixation. Surgical gastrostomies commonly use Foley balloon catheters, mushroom-tip de Pezzer catheters, or Malecot catheters. Some internal bolsters are deformable and allow removal with gentle traction on the external tube. Others are not intended to give way with traction and require more invasive techniques for removal. The nature of the internal bolster will determine if a G-tube can be removed in the Emergency Department or requires endoscopic removal. Premature removal of a tube in an immature tract, particularly if it is endoscopically placed, can lead to gastric spillage and peritonitis. A conservative approach is to consider any tract less than 4 weeks old to be immature. The specialist who performed the original procedure should be consulted prior to any manipulation of the immature tract. Then, while providing traction on the tube, press a flat, gloved hand against the abdominal wall for countertraction.

Effective diabecon 60 caps

Cottontipped applicator with silver nitrate matchstick taped to the opposite side diabetes telltale signs purchase diabecon 60 caps line. These trays are available from the Operating Room, hospital central supply, or the surgical clinics. The trays may contain disposable single-use instruments or multiuse instruments depending on the institution. The shaft is approximately 30 to 40 cm in length and has 1 cm increments marked on the outside. The distal end of the obturator is smooth, occludes the shaft of the scope, and projects 1 to 2 cm distal to the scope. Discuss the order of examination, the importance of relaxing, the reason for multiple insertions and withdrawals of the rigid rectosigmoidoscope, and what you expect to find. It is important to explain the reason for insufflating air and how this may produce discomfort. Explain that the procedure should not require procedural sedation and that the patient should inform the Emergency Physician of any discomfort. Assure the patient that the complaint of pain will at least temporarily stop the examination. While it is possible to perform an examination with rigid rectosigmoidoscopy on an unprepared rectum, more information about the mucosa will be obtained if the bowel has been prepared. Two 4-ounce phosphate soda enemas given at 2 hours and 1 hour before the examination will provide adequate preparation in most patients. The preparations used for colonoscopy are expensive, involve too much preparation, and cause patient discomfort for the extent of the examination. The judicious use of intravenous sedation may be required in some patients who are anxious. The eyepiece on the proximal end of the scope should open easily, close easily, and seal against the rigid rectosigmoidoscope. Open the eyepiece and insert the obturator completely within the rigid rectosigmoidoscope. The bulb of the insufflator must pump air into the rigid rectosigmoidoscope and should reinflate after the bulb is released. Liberally lubricate the distal 5 cm of the rigid rectosigmoidoscope and the obturator. Examination in this position is relatively easy and less air inflation is required during the procedure, thus reducing patient discomfort. Examination in this position requires some experience and is not recommended for novices. The Emergency Physician should be prepared with an impermeable gown and one glove on the left hand and two on the right hand (if right handed). As in anoscopy, it is important to carefully inspect the entire perineum and anal verge prior to the examination. Many types of pathology such as fissures, fistulas, hemorrhoids, condylomata, and dermatologic conditions may be seen at this time. Digital rectal examination with a well-lubricated, gloved finger is mandatory prior to rigid rectosigmoidoscopy. This step allows the examiner to find pathology that is better palpated than viewed and allows greater focus on a specific area. It will also allow the examiner to evaluate the size and angle of the anal canal, assess for patient sensitivity or tenderness prior to rectosigmoidoscopy, and prelubricate the anal canal making insertion of the rigid rectosigmoidoscope easier. Use 2% lidocaine jelly as a lubricant and to provide some local anesthesia if the patient has pain from excoriation. Remove the extra glove from the dominant hand before picking up the rigid sigmoidoscope. Grasp the handle of the rigid rectosigmoidoscope with the right, Reichman Section5 p0657-p0774. The left lateral decubitus position on an examination table with the buttocks extended over the edge of the table. The left (nondominant) hand is placed on the buttocks and used to spread the buttocks. The right (dominant) hand is used to insert and advance the scope while the thumb keeps the obturator properly seated. This is necessary so that if the patient moves, the instrument will move with the patient. The sigmoid colon can also be identified by the presence of transverse folds that are lacking in the rectum. It is necessary to use the rigid rectosigmoidoscope to gently straighten the colon while completely inserting the instrument to a depth of 25 cm. Maintain communication with the patient, inform them of what is happening, and ensure patient comfort throughout the procedure. Open the eyepiece if it becomes clouded with moisture and wipe it with dry gauze so the view is kept clear. This flattens out the haustra and valves of Houston so that the entire mucosal surface can be viewed. The nondominant hand stabilizes the scope while the dominant hand advances it under direct visualization. Open the eyepiece just prior to completely removing the rigid rectosigmoidoscope to release as much of the insufflated air as possible. The viewing window, which seals in the air, must be opened if it is necessary to biopsy or to grasp something. The obturator should be reinserted if it is necessary to reinsert or readvance the rigid rectosigmoidoscope. The rectosigmoid junction is located approximately 16 cm from the anus, where the rectal lumen turns anteriorly and to the right. The rigid rectosigmoidoscope is rotated in a circular motion while simultaneously withdrawing the scope and visualizing the mucosa. They may experience mild discomfort, flatus, and spotting of blood in the stool for several hours. Instruct the patient to immediately return to the Emergency Department if they develop a fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bright red blood per rectum, or if they have any concerns. Follow-up should be arranged with a Family Practitioner, Internist, Gastroenterologist, or Surgeon depending on the findings of the examination. The most frequent types of items found in the anus from ingestion are undigested fish or chicken bones. It is important to attempt to identify the characteristics of the foreign body to devise the safest method of removal. The glue that attaches the metal base to the glass loosens with moisture and time. If the glass breaks, it may take a long time to remove the fragments and cause considerable damage to the surrounding rectal mucosa or the examining finger. The idea is to remove the foreign body without causing further damage to the rectum or the anal sphincter muscle. The more knowledge the Emergency Physician has about the foreign body and how it was inserted, the more likely it is that it will be removed safely. Perforation can occur with forceful insertion of the instrument without viewing the colonic lumen or if the patient moves suddenly and the scope is not supported properly. Trauma to the mucosa from the rigid rectosigmoidoscope or instrumentation from related procedures. Brisk bleeding can be controlled by the judicious use of a silver nitrate matchstick. An important anatomic consideration in removing rectal foreign bodies include the axis of the lumen of the anus. When the object is being removed by bringing the distal end anteriorly, the middle portion may push anteriorly. The important physiologic considerations include the anal sphincter muscles, edema, and the creation of a vacuum.

Diabecon 60caps low price

The initial resuscitation to achieve hemostasis is paramount in the Emergency Department and often overshadows the search for the underlying etiology blood sugar 66 discount diabecon 60caps without a prescription. The origin of the bleeding directs the algorithm for further management after stabilization. There have been more than two million video capsule endoscopies performed worldwide and thousands of research papers on its various aspects. An Emergency Physician must be familiar with its potential complications and current limitations. The foregut gives rise to the abdominal esophagus, the stomach, the proximal half of the duodenum, the liver, the gallbladder, and the pancreas. The hindgut gives rise to the distal third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and the proximal anal canal. It should be noted that the branches of these arteries frequently anastomose with each other and provide alternative routes of arterial supply. The common hepatic artery supplies the liver, gallbladder, stomach, duodenum, and pancreatic head and neck. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery supplies the head of the pancreas and the duodenum. The ileocolic artery supplies the ileum, cecum, appendix, and proximal ascending colon. The left colic artery supplies the distal transverse colon and the descending colon. The portal vein is the main venous drainage system and is formed by the combination of the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic veins. The superior mesenteric vein drains portions of the foregut and all of the midgut. The splenic vein drains the spleen, pancreas, portions of the foregut, and all the hindgut derivatives via the inferior mesenteric vein. Similar to the arterial supply, the portal system has many anastomoses that prevent total occlusion should one of the major veins become obstructed. This ligament is a suspensory ligament classically attached to the distal segments of the duodenum or the duodenojejunal flexure, although considerable anatomic variation exists. The designation of upper versus lower remains essential as the pathophysiology greatly varies, the secondary diagnostic modalities differ, and the therapeutic modalities differ. Other causes include focal nodular hyperplasia, portal vein thrombosis, schistosomiasis, and idiopathic. Intrahepatic is the case with cirrhosis or other liver disease affecting hepatic sinusoidal blood flow. The excessive pressure can cause the variceal veins to rupture and hemorrhage due to poor vascular wall strength. It is imperative to distinguish variceal bleeding from other etiologies when the undifferentiated patient enters the Emergency Department due to the high mortality rate of variceal hemorrhages. This includes the primary survey, hemodynamic stabilization, airway management, clinical scoring systems for risk stratification, the use of a nasogastric tube, capsule endoscopy or other means to determine the bleeding etiology, the use of initial antibiotics if a variceal bleed is suspected, the use of pre-endoscopic erythromycin to increase endoscopy diagnostic yield, and a proton pump inhibitor to increase the gastric pH to stabilize the clot. It is the direct visualization and stabilization of the lesion with the use of bipolar electrocoagulation, banding, sclerosant clips, or a heater probe. Third is the pharmacological management beyond the initial resuscitation measures. This involves longer term management such as continuous proton pump inhibitor infusions, treatment of suspected H. This includes surveillance for the possibility of rebleeding and alternative management if bleeding remains refractory. These include a thorough history and physical examination followed by clinical scoring systems. The pertinent medical history is also important to obtain, especially a history of liver disease or other comorbidities that may predispose to complications with management. Examples are heart or lung disease predisposing to subsequent hypoxemia, cancers or leukemias and their treatments that hinder coagulation, or dementia or hepatic encephalopathy, which increases the risk of aspiration. For example, several episodes of nonbloody emesis followed by hematemesis make a Mallory-Weiss tear more likely, versus a sudden onset of copious hematemesis, which is more characteristic of a variceal bleed. The objective appearance of the blood may help determine if there is a significant risk of hemorrhage. The Glasgow-Blatchford scale aims to predict which patients will eventually require intervention in the form of blood transfusion, endoscopy, or surgery. The Glasgow-Blatchford scale was found to be far superior in its respective goal compared to the Rockall score in terms of negative predictive value since none of the patients with a score of 0 on the Glasgow-Blatchford scale required endoscopy. This confirmed the findings of a similar earlier pilot study, which predicted 100% of the highand low-risk patients. The removal of stomach contents may enhance visualization of the anatomy when an endoscopy is later performed. There was a statistically significant correlation between a bloody lavage and high-risk lesions on subsequent endoscopy, with an odds ratio of 4. A study compared the use of erythromycin alone versus nasogastric lavage plus erythromycin as a means to prepare patients for subsequent endoscopy. Based on this study, it is not necessary to rely on nasogastric lavage to improve visualization during endoscopy. Nasogastric lavage has not shown any significant improvement in the patient outcomes of mortality, hospital length of stay, or the need for subsequent transfusions. Video capsule endoscopy is much less invasive, better tolerated, and has been shown to have more consistent results than nasogastric aspirate and lavage in relatively small studies. Of the 17% of bleeding lesions missed, approximately one-third of missed bleeds were due to battery death before reaching the duodenum. This study also found that there was no significant difference between the identification of peptic or inflammatory lesions between capsule endoscopy and upper endoscopy, although upper endoscopy remains the gold standard. The results from video capsule endoscopy are easy to interpret and do not require specialist training. Video capsule endoscopy is a cost-effective method for early lowrisk bleeding detection and risk stratification when compared to the Glasgow-Blatchford scale (and all further testing it required), nasogastric lavage, and an admit-all strategy using standard decision analysis software. Protection of the airway and initial resuscitation from blood loss always takes precedence over all further diagnostic studies. In patients with altered mental status, dementia, or swallowing difficulties, aspiration of the capsule can occur. Known dysphagia, esophageal strictures, esophageal webs, or disorders that may potentially hinder the passage of the capsule through the digestive tract. It has also been proposed that patients with cardiac pacemakers or defibrillators should not be considered candidates for video capsule endoscopy due to potential radiofrequency interference. However, multiple studies have shown that video capsule endoscopy can be used safely with pacemakers and defibrillators, and therefore, these are a relative contraindications. Pregnancy is considered a relative contraindication to the use of video capsule endoscopy. This is due to the increased risk of impaction requiring surgical intervention and thus potential harm to the fetus. Consult a Gastroenterologist before performing video capsule endoscopy on these patients. The data from the lenses is transmitted via ultra-high-frequency band radio telemetry through the sensory pads and belt to the data recorder, which then transmits the date to the computer or handheld device. The studies evaluating the success of video capsule endoscopy discussed earlier took this aspect into account, and all results were in patients who lacked the ideal preparation. The main preparation required prior to this procedure is initial stabilization of airway, breathing, and circulation as well as assessing for and ruling out any significant contraindications. The patient and/or their representative must be informed of the procedure, including its risks and benefits. Obtain plain radiographs of the abdomen to make sure there is no bowel obstruction prior to the procedure. They differ in regard to their battery life, field of view, dimensions, image requisition, and optics. Instruct the patient to drink approximately 100 mL of water while standing followed by the ingestion of the activated capsule in the supine position with a 10 mL sip of water through a syringe or straw. After 2 minutes of recording in this position, place the patient in an upright seated position while the rest of the images are recorded. After the 30 minute of recording, the capsule automatically deactivates and is passed through the intestine via peristalsis, leading to the eventual natural evacuation.

Quince. Diabecon.

- How does Quince work?

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- Dosing considerations for Quince.

- What is Quince?

- Are there safety concerns?

- Digestive disorders, diarrhea, coughs, stomach and intestinal inflammation, skin injuries, inflammation of the joints, eye discomfort, and other conditions.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96398

Discount 60 caps diabecon visa

Percutaneous cannulation can be achieved rapidly and is straightforward once arterial and venous access is established diabetes ii definition order discount diabecon on-line. Shinar Z, Bellezzo J, Paradis N, et al: Emergency department initiation of cardiopulmonary bypass: a case report and review of the literature. Lamhaut L, Jouffroy R, Soldan M, et al: Safety and feasibility of prehospital extra corporeal life support implementation by non-surgeons for out-ofhospital refractory cardiac arrest. Anton-Martin P, Braga B, Megison S, et al: Craniectomy and traumatic brain injury in children on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: case report and review of the literature. Bedeir K, Seethala R, Kelly E: Extracorporeal life support in trauma: worth the risks Butt W, MacLaren G: Concepts from paediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult intensivists. Combes A, Brechot N, Luyt C-E, et al: What is the niche for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome Robba C, Ortu A, Bilotta F, et al: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory distress syndrome in trauma patients: a case series and systematic literature review. Rozencwajg S, Pilcher D, Combes A, et al: Outcomes and survival prediction models for severe adult acute respiratory distress syndrome treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Hu W, Chen L, Liu C, et al: Three cases of electrical storm in fulminant myocarditis treated by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Hwang H-W, Yen H-H, Chen Y-L, et al: Prolonged pulseless electrical activity: successful resuscitation using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Khorsandi M, Dougherty S, Young N, et al: Extracorporeal life support for refractory cardiac arrest from accidental hypothermia: a 10-year experience in Edinburgh. Koschny R, Lutz M, Seckinger J, et al: Extracorporeal life support and plasmapheresis in a case of severe polyintoxication. Mohan B, Gupta V, Ralhan S, et al: Role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in aluminum phosphide poisoning-induced reversible myocardial dysfunction: a novel therapeutic modality. Maekawa K, Tanno K, Haes M, et al: Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of cardiac origin: a propensity-matched study and predictor analysis. Fair J, Tonna J, Ockerse P, et al: Emergency physician-performed transesophageal echocardiography for extracorporeal life support vascular cannula placement. Kashiura M, Sugiyama T, Tanabe T, et al: Effect of ultrasonography and fluoroscopic guidance on the incidence of complications of cannulation in extracorporeal resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a retrospective observational study. Lubnow M, Philipp A, Dornia C, et al: D-dimers as an early marker for oxygenator exchange in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation J Crit Care 2014; 29(3):473. Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, et al: In-hospital mortality and successful weaning from venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of 5,263 patients using a national inpatient database in japan. Tauber H, Ott H, Streif W, et al: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation induces short-term loss of high-molecular-weight von Willebrand factor multimers. Bunya N, Sawamoto K, Uemura S, et al: Cardiac arrest caused by sibutramine obtained over the internet: a case of a young woman without pre-existing cardiovascular disease successfully resuscitated using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Chiu C-W, Yen H-H, Chiu C-C, et al: Prolonged cardiac arrest: successful resuscitation with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Chiu C-C, Yen H-H, Chen Y-L, et al: Severe hyperkalemia with refractory ventricular fibrillation: successful resuscitation using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Aneman A, Macdonald P: Arteriovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiac arrest/cardiogenic shock. Arlt M, Philipp A, Voelkel S, et al: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe trauma patients with bleeding shock. Barrou B, Billault C, Nicolas-Robin A: the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in donors after cardiac death. Bouabdallaoui N, Mastroianni C, Revelli L, et al: Predelivery extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a life-threatening peripartum cardiomyopathy: save both mother and child. Brunner M-E, Siegenthaler N, Shah D, et al: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support as a bridge in a patient with electrical storm related cardiogenic shock. Other options include proximal control with the use of embolization, surgical closure, or tourniquets. Aortic occlusion is one hemorrhage control method that temporarily stops noncompressible torso hemorrhage from injuries that receive blood supply from the subdiaphragmatic aorta. Aortic occlusion improves hemostasis, preserves coronary and cerebral perfusion, and can improve hemodynamics enough to allow for definitive hemorrhage control by embolization, endoscopy, or surgical repair. It can be performed at the bedside in the Emergency Department without the risks associated with patient transport. Consider early femoral artery access in patients at high risk of developing hemorrhagic shock (Chapter 72). Obtaining arterial access is difficult in hypotensive patients or after cardiopulmonary arrest. Elevated lactate and other cytokines may have significant effects on patient physiology, especially after balloon deflation. Use caution in patients with peripheral vascular disease or prior femoral artery procedures as their anatomy may be more challenging and increase the risk of complications. There are two ports, one for the balloon inflation/deflation and the other for guidewire placement. There are two ports, one for balloon inflation/deflation and a proximal arterial line port for monitoring pressures in the aorta proximal to the occlusion. Further steps in management will be described briefly as they take place after hemorrhage control with the patient in the care of the inpatient team. Document the reason for not having a consent in the record if there is no time for it to occur. The approach using anatomic landmarks involves palpating for the femoral pulse and aiming 1 to 2 cm inferior to the inguinal ligament. Identifying the femoral artery may be challenging in hypotensive patients without palpable pulses. The Emergency Physician should have experience using a femoral artery cutdown if it is to be performed. Always occlude the open hub of a catheter, needle, or sheath to prevent an air embolism. Doing so may injure the vessel, break the guidewire, and/or embolize the guidewire. If there is doubt about the exact location of the femoral artery, it may first be located with a small "finder" needle. Insert a 25 or 27 gauge needle attached to a 5 mL syringe through the skin puncture site previously chosen. Inject a small amount of the fluid in the syringe to remove any skin plug that may block blood return once the artery has been penetrated. Stop advancing the introducer needle if the artery is not located within 3 to 5 cm of the skin. Avoid putting continuous pressure on the femoral artery pulse as even gentle pressure may collapse it. The femoral artery has been entered if the blood is bright red and/or forces the plunger of the syringe back. Even a millimeter of movement may result in failure to stay within the lumen of the artery. One end of the guidewire must always be held to prevent its loss and embolization. Do not simply reverse the guidewire if the sleeve used to straighten the curved end of the guidewire is lost. Guidewire resistance may indicate that the introducer needle is not within the artery, is against the wall of a vessel, or is caught as the vessel bends. The use of force will kink the guidewire and may cause it to damage the artery and adjoining tissues. A slight twisting motion of the dilator as it is advanced may aid in its insertion. Continue to apply the next size dilator, advance it, and then remove the dilator until the appropriate size is used.

Order diabecon online from canada

There was no correlation between the time to intubate and any of the airway prediction variables in the Trachlight group in a series of 950 patients diabetes mellitus range buy 60 caps diabecon overnight delivery. Both are associated with varying degrees of sympathetic activity, which may be detrimental in patients with coexisting conditions. Several investigations of the possibility that lighted stylet intubation may result in less stimulation than direct laryngoscopy and may offer some protective effects from sympathetic hyperactivity did not confirm this to be true. There is some tendency for lower blood pressure and heart rate in a lighted wand group. Patients with laryngeal trauma should have direct laryngeal visualization for intubation rather than a blind technique that may cause additional trauma. Do not use a lighted stylet if there is any active infection or known tumor of the posterior pharynx or upper airway. It may be less successful in bright sunlight, obese patients, and patients with very dark skin. It can be used in this situation by very experienced Emergency Physicians while simultaneous preparations are under way for a cricothroidotomy (Chapter 32). Lighted stylets should be used only by Emergency Physicians who have sufficient experience and training with the equipment and the technique. Abandon the technique and use an alternative method to intubate the patient if unexpected difficulty occurs during its passage. Rapid sequence intubation (Chapter 16) with an induction agent and paralytic agent is the most common technique used in the Emergency Department. Lighted stylet intubations can be performed with mild sedation and topical anesthesia in cooperative patients. The anterior half of a cervical collar must be opened or the entire collar removed to be able to visualize the glowing light. An assistant can maintain in-line stabilization of the cervical spine when the collar is opened or removed. The reader is urged to take advantage of the teaching videos supplied by some manufacturers. Check that the light source is working and apply a water-based lubricant to the stylet. Place the index finger in the submental space below the chin and determine the number of finger breadths between the mandible and the hyoid bone. The lighted stylet, unlike the traditional laryngoscope, can be held in either hand. Place the nondominant thumb on the mandibular molars and the nondominant fingers under the body of the mandible. Lift upward and inferiorly to open the jaw, elevate the tongue, and elevate the epiglottis. The handle contains the battery, on-off switch, and sometimes an onoff indicator light. It is likely that further developments will continue to make these and similar models attractive options in airway management. The bright light transilluminates the anterior neck as the lighted stylet approaches the trachea. A bright light may be visible when the stylet is in the esophagus in the thin patient. Gently rock the light off midline to compare the diffuse dull light to that seen when the light is truly midline. Appearance of the transilluminated light of the lighted stylet based on the location of the tip. Proper placement in the larynx with a bright distinct light in the midline at the level of the thyroid cartilage. Incorrect placement in the vallecula causes a submental glow superior to the hyoid. These include two reports of accidental bulb dislodgment, two arytenoid dislocations, one case of stylet fracture, a lacerated frenulum, and varied reports of mild soft tissue trauma. There are data to suggest that lighted stylet intubations are less traumatic than direct laryngoscopy. Weis and Hatton reported no complications in 253 patients intubated with a lighted stylet. Success rates on first attempts are reported to be as low as 70% with the Tube-Stat and as high as 92% with the Trachlight. Hung and colleagues reported the successful intubation in 95 of 96 known difficult airways. Holzman and colleagues reported successful intubation in 30 of 31 children with anatomic airway abnormalities. There is a definite learning curve, and time to intubation improves with experience. A bright and well-circumscribed glow (arrow) is seen below the thyroid prominence when the lighted stylet enters the glottis. The brief loss or dulling of the glowing light corresponds to its passage behind the larynx. Gently withdraw the lighted stylet while applying anteriorly directed traction to the tip of the stylet. Stop withdrawing the lighted stylet when the glowing light suddenly intensifies after it exits the esophagus. Readvance the lighted stylet, as previously described, while applying anterior traction on the unit to help it enter the larynx. Treat the nasal passages with a topical anesthetic and a topical decongestant to vasoconstrict the mucosal tissue (Chapter 29). The bend-to-tip length should correspond to the distance from the posterior nasopharynx to the cricothyroid membrane. It is particularly useful in patients with limited jaw opening, limited neck movement, and marked airway bleeding. The American Society of Anesthesiologists includes use of lighted stylets in its recommendations for the management of difficult airways. The success of lighted stylet techniques is determined by the experience of the Emergency Physician. This technique is likely to be of greatest benefit in the occasional unexpected airway emergency. Emergency Physicians will need to devote time and effort to developing and maintaining the skills they will need to cope with an airway emergency when it presents. American Society of Anesthesiologists: Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway. Davis L, Cook-Sather S, Schreiner M: Lighted stylet tracheal intubation: a review. The majority of advanced airway interventions in the prehospital environment occur in the cardiac arrest or major trauma patient with significant altered mentation. A baseline proficiency in airway management via intubation requires on the order of 50 to 100 intubations, a clinical experience not commonly found in the prehospital training environment. This allows for progression to continuous uninterrupted compression cycles with interposed ventilations. It was created in 1981 and is used daily in Operating Rooms across the world with several hundred million cumulative cases of patient care experience. The device migration from the Emergency Department to the prehospital arena has begun. An explosion of new devices in a very competitive marketplace could easily overwhelm the Emergency Physician as to the nuances of devices and brands. It is difficult for Emergency Physicians to keep up with the industry explosion of these airway adjuncts. The use as a rescue device can "buy time" until additional airway assistance, equipment, and/or expertise can be brought to the patient. Trauma to the upper airway is a relative contraindication to placement of these devices. These devices are contraindicated in the patient with a caustic ingestion or airway burns.

Purchase diabecon 60 caps without prescription

Cut out wedges of plaster in order to minimize buckling at the malleoli as the splint material wraps around the heel diabetes insipidus webmd buy cheap diabecon on line. Holding the leg by the toes may allow the force of gravity to disrupt fracture alignment. The patient can sit upright on the edge of the gurney with the affected leg hanging down freely if no assistant is available. The knee and tibial tuberosity are left entirely free to allow for full flexion and extension. The toes can be left entirely exposed or the cast can provide a hard sole of support and protection beneath the toes. Apply cotton cast padding with extra attention to the areas of bony prominence such as the fibular head, the lateral malleolus, and the medial malleolus. Apply the casting material from the calf to the toes as if applying a short arm cast. Mold the casting material around the Achilles tendon, away from the malleoli, and to conform to the plantar arch. Cut the wet casting material under the metatarsal heads to expose the toes or leave it long to support the entire toes. Supplement the arched foot of the short leg cast with additional casting material to form a flat surface. Apply a preformed heel after the cast has completely dried to prevent any indentation. Place the walking heel in the midsagittal plane of the foot with the center aspect lining up with the anterior calf. The cast extends from the metatarsal heads to several finger breadths below the groin. Be sure to provide sufficient overlap of casting material at the junction between the two casts. This includes increased pain, pain with passive motion, paresthesias, pallor, decreased or altered sensation, as well as delayed capillary refill. The patient should return to the Emergency Department immediately if they develop any of these symptoms, if the digits become cold or blue, or if the patient has other concerns. The extremity should be maintained above the level of the heart for the first 48 to 72 hours after the injury. Ice should be applied to the surface of the cast or splint for at least 15 minutes three times a day. The cold therapy will be transmitted through the cast or splint and result in significant reduction of edema. Active motion of the fingers and toes should be encouraged to help reduce edema in the extremity. Should bathing be desired, instruct the patient to place two plastic bags over the extremity and tape the proximal edge to the skin of the extremity. Sufficient pain medication should be supplied to last the patient until their follow-up visit with an Orthopedic Surgeon. This should include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs supplemented with narcotic analgesics. Measure the extremity starting 10 inches above the patella to 10 inches below the patella. Make a cut in the folded side extending from one edge to the middle of the folded side to create a hinge. Apply cotton cast padding starting 10 inches above the patella to 10 inches below the patella. Place the hinged portion of the splinting material 10 inches below the anterior patella with the cut ends extending proximally up both the medial and lateral leg. Great care should be taken in applying a cast or splint and only molding it with the broad surfaces of the hands. Molding with the fingers can result in indentations and localized areas of pressure. The cast or splint should never be allowed to rest on a hard or pointed surface until it is completely dry. Points of contact on the hard surfaces may cause impressions that result in increased pressure. If the pressure point is not addressed rapidly, the pain will often subside as the skin becomes necrotic. This oversight often results in a foul-smelling pressure sore under the cast or splint when the patient returns for follow-up. Cast and splint treatment may be rife with complications for patients with limited sensation from underlying medical conditions. Great care should be taken and extra padding used when casting or splinting these individuals. Common areas of pressure necrosis also include the proximal and distal ends of the cast or splint. Great care should be taken in padding the ends of the cast or splint during the application. If the edges of the splint are sharp or too long, they should be folded out and away from the patient. The rigid immobilization prevents soft tissue expansion from edema and decreases the amount of fluid needed to raise compartment pressures. For example, after casting a distal radius fracture where a dorsal mold is needed to maintain the reduction, split the cast longitudinally on the volar and dorsal surfaces. Splinting greatly reduces the chance of iatrogenic-induced compartment syndromes because, unlike casting, splints do not harden circumferentially. The plaster and underlying cotton cast padding must be split to visualize the skin underneath. Do not use standing or previously used water, as it is an excellent culture medium. All wounds should be dressed with sterile gauze and cotton cast padding prior to applying the cast or splint. Patients should be instructed to keep casts and splints clean and dry so as to prevent skin maceration. Orthopedists and orthopedic technicians may develop a contact dermatitis from continued exposure to plaster over many years. Sometimes the immobilization is unavoidable, as with the incorporation of the ankle and the knee in a long leg cast. Every effort should be made to decrease adjacent joint immobilization as soon as it is safe and practical. Immobilize the extremity in a position of function as long as this does not interfere with the maintenance of fracture reduction. For example, take great care not to immobilize the ankle in plantarflexion when applying a lower extremity splint or cast. Second, extend the cast proximally to become a short leg cast and mold the reduction. Every effort should be made to leave the fingers mobile at the metacarpophalangeal joints. Immobilization of the metacarpophalangeal joints in extension results in shortening of the collateral ligaments and limitation of flexion. This position keeps the collateral ligaments in a lengthened position and allows a rapid return to function. Fractures and dislocations of the extremities are routinely handled in the Emergency Department with prompt Orthopedic follow-up or consultation. The application of external immobilization can be the definitive or temporizing management of the injured extremity. The application of splints accounts for the majority of immobilization of injured extremities.