Buy cheapest altace and altace

Meticulous closure of the anterior hairline is essential for a successful cosmetic outcome blood pressure pump purchase 1.25 mg altace otc. The main disadvantages of this approach are potentially a more visible incision compared to the endoscopic approach and paresthesia behind the incision line. In all brow-lifts, regardless of the surgical approach, the plane of dissection over the skull can be either subperiosteal or subgaleal. The temporal incision is extended down to the superficial layer of the deep temporalis fascia. Using a freer elevator, the dissection is continued along this plane and the temporal dissection is connected to the subperiosteal plane of the forehead by sharply 2498 dissecting the transition zone at the temporal crest line. The temporal dissection is continued to the level of the zygomatic arch and the zygomaticofrontal suture line. If the dissection is in the correct plane, the temporal fat pad in the elevated flap should become visible as one nears the zygomatic arch. A branch of the zygomaticotemporal communicating vein ("sentinel vein") is often encountered when dissecting near the zygomaticofrontal suture line. The vein can either by cauterized with a bipolar cautery or gently dissected from the surrounding tissue. Bleeding caused by injury to this vein can lead to poor visualization, and possibly inadvertent injury to the facial nerve from cauterization or further dissection. Overzealous upward retraction in the temporal area should be avoided as it may cause traction neuropraxia of the frontal branch of the facial nerve. It is important to release fully the entire length of the superior arcus marginalis to achieve adequate brow elevation. The periosteum and galea are horizontally scored at this point, exposing the corrugator muscle, procerus muscle, supraorbital nerve, and supratrochlear nerve. In patients in whom glabellarmuscle modification is desired, the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves are dissected from the corrugator muscles by using a gentle vertical spreading motion with Takahashi forceps. Once the nerves are safely separated from the corrugator muscle, the muscle is gently avulsed or transected. Care should be taken not to remove any subcutaneous tissue, as dimpling or contour irregularities will occur. It is not necessary to remove all of the muscle fibers to achieve the desired result; the extent of the resection should be tailored to the preoperative assessment of the severity of the glabellar frown lines. Surgeons differ in their use of fixation methods to reposition the forehead soft tissues. In the endoscopic approach, the anterior corner of the incision is engaged and secured to the desired point on the temporalis fascia, determined by the desired vector pull. Regardless of the method of fixation, adequate dissection and mobilization of the forehead tissue are paramount for successful brow elevation. In the skin excision techniques, deeper fixation is not necessary; but, as mentioned above, 2499 complete release and mobilization of the brow and forehead are necessary for a successful outcome. A screw is placed at the posterior extent of the vertical incision and the scalp complex is advanced posteriorly. Surgery of the upper eyelids involves excision of an ellipse of skin, just superior to the tarsal crease. In patients in whom the natural crease is not well demarcated, the lower incision is made 10 to 11 mm above the lash line in women and 8 to 10 mm above the lash line in men. The shape of the excised skin is generally elliptical, with the incision tapered gently medially and wider laterally to address lateral hooding. The incisions must be drawn symmetrically or in such a way to account for preoperative asymmetry. If a brow-lift is to be performed, it is performed first to prevent excessive removal of upper-eyelid skin during blepharoplasty. Once the skin and subcutaneous skin is removed, the orbicularis muscle is divided which reveals the fine connective tissue of the orbital septum. In some patients, a strip of obicularis muscle can be removed paralleling the skin incision to accentuate the creation of the upper-lid crease or to remove hypertrophic muscle. The fat is conservatively removed from the medial and middle compartments, and hemostasis is meticulously obtained. Surgical approaches used to remove prolapsed fat from the lower eyelids can be performed through subciliary or transconjunctival incisions. The subciliary approach is generally selected when excess lower lid skin must be excised. When this approach is used, care must be taken to assess the laxity of the lower lid. By using a "snap" or "pinch" test, the resiliency of the lower lid can be ascertained. When a lower lid is pulled down and slowly returns to its original position or is pinched and slowly returns to touching the globe, a tarsal suspension procedure must be performed to prevent postoperative ectropion. The transconjunctival approach to the lower lids was developed mainly to prevent ectropion. After performing the lower-lid incision, the three orbital fat compartments (medial, central, lateral) are exposed. Because the fat pads retract after manipulation, meticulous hemostasis is necessary to prevent an orbital hematoma. Increased pressure in the globe from a hematoma can cause a decrease in retinal artery flow and potentially result in blindness. Once the three fat pads are isolated, conservative removal of fat from the lateral compartment is performed. The white band of the arcus marginalis is identified on the bony infraorbital rim and divided, exposing the anterior maxilla. Dissection can instead be performed in the supraperiosteal plane, but dissection through the orbicularis muscle makes this a bloodier plane. The fat pad is dissected to allow sufficient rotation, and the pedicle is thinned to a width of 0. The pedicled fat pad is actually a random flap, despite the presence of somewhat large feeding vessels. Once the fat is positioned, a forced duction test of the globe is performed to ensure no restriction of extraocular movement with upward gaze. The longterm fat survival rate may vary, but most patients maintain improvement in the nasojugal region. Hypesthesia over the forehead and scalp due to traction neuropraxia of the sensory nerves is usually temporary and returns to normal in six to 10 weeks. There have been some anecdotal reports of temporary weakness of the frontal branch of the facial nerve following the procedure. Imprecise surgical technique may result in asymmetrical brows, excessive brow elevation or, more commonly, recurrence of brow ptosis. Sufficient release of the brow at the level of the orbital rim and adequate fixation will prevent the recurrence of brow ptosis. There may be some temporary local alopecia at the incision sites, and bunching of the skin usually resolves in two months. Blepharoplasty Asymmetry of the upper eyelid tarsal creases is a risk of upper blepharoplasty. Failure to recognize a lid ptosis preoperatively can result in an asymmetric result. Lagophthalmos, the inability to close the lid, can result from excessive upper lid skin excision. For that reason, the young surgeon is cautioned to remove conservative amounts of skin during upper lid blepharoplasty. If necessary, redundant skin may be removed after the patient has healed, but it is difficult to replace skin postoperatively if the lid is too short. Occasionally a fat pad is inadequately excised, and a noticeable prominence is present especially on upward gaze. These prominences can usually be removed easily by the transconjunctival approach. Serious complications of blepharoplasty include injury to the ocular muscles and hematoma. A hematoma of the upper lid is not as serious a problem as it is in the lower lid.

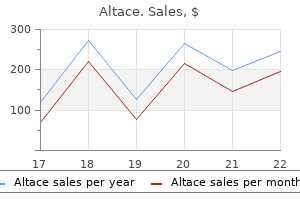

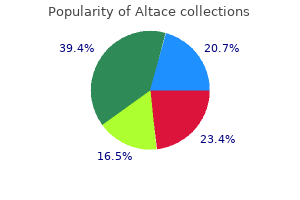

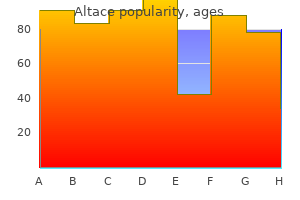

Generic 2.5mg altace free shipping

A vertical incision is carried inferiorly to the midpoint between the middle turbinate insertion and inferior turbinate 04 heart attack m4a cheap 5 mg altace overnight delivery, and finally posteriorly to the uncinate process. Next, a suction elevator is used to elevate the mucosal flap, identifying the important maxillary line. Once this is done, the thin lacrimal bone is removed with a curette, and the thicker frontal process of the maxilla is partially removed with a rongeur or punch. The remainder of the frontal process of the maxilla superior to the axilla of the middle turbinate may be removed with a powered diamond burr. After the lacrimal sac has been completely exposed, especially superiorly, the inferior or superior punctum is dilated and the sac is cannulated with a lacrimal probe. When the probe is visualized tenting the sac medially, a vertical incision is made along the length of the sac, followed by superior and inferior relaxing incisions horizontally. The redundant anterior and posterior lacrimal sac flaps can either be resected or reapproximated with the original flap of nasal mucosa. After this is done, silastic stents are placed within the lacrimal apparatus and secured intranasally. They recommend routine evaluation of the inferior meatus in patients with epiphora. As expertise, instrumentation, and technology have advanced, so too have the applications of endoscopic sinus surgery. With the advent of tools such as powered instrumentation, angled burrs and curettes, and image-guided surgery, the endoscopic endonasal approach is now being used routinely for the resection of multiple types of benign sinonasal neoplasms, including those with extensive skull base, intracranial, or intraorbital extension. In selected patients, the endoscopic approach allows for complete tumor resection, shorter hospital stays, minimal blood loss, no external incision, and less overall morbidity as compared to traditional open approaches. Endoscopes provide greater magnification and visualization of sinonasal lesions and enable a more precise resection as well as identification and preservation of certain vital structures. T1 weighted images can be used to differentiate between post-obstructive secretions and soft tissue. Benign sinonasal neoplasms are a diverse group that may have similar clinical 2307 presentations. Common presenting symptoms include nasal obstruction, epistaxis, epiphora, rhinorrhea, and recurrent sinusitis. Patients may also be asymptomatic, presenting with lesions discovered as incidental findings on imaging studies ordered for non-rhinologic purposes. Although several of these lesions may have characteristic presentations, as well as endoscopic and radiographic findings, final diagnosis rests on pathological analysis of a biopsy specimen. Although their appearance and presentation may be somewhat similar, their clinical implications vary tremendously. Most lesions are benign, but many exhibit a slow, steady progressive growth pattern with resultant local infiltration, cosmetic change, and/or post-obstructive sinusitis. Gardner syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple osteomas, soft tissue tumors (such as epidermal inclusion cysts or subcutaneous fibrous tumors), and colorectal polyposis. It is caused by a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene on chromosome 5q. Early diagnosis is crucial, as the colorectal polyps have a high incidence of malignant degeneration. In the developmental theory, the apposition of endochondral and membranous tissues traps embryonic cells, leading to osseous proliferation. Moretti and colleagues reported that approximately 20% of sinus osteomas occur as a result of trauma. Similarly, Sayan and colleagues reported that osteomas of the mandible occur commonly in places where muscles insert into the bone; resultant muscle traction may incite minor trauma leading to inflammation and subsequent osteoma formation. This, however, does not explain lesions developing in patients without a history of infection or osteitis. The eburnated type, also known as the compact type, consists of dense bone, and lacks Haversian canals. Common symptoms and signs include frontal pain and headache, as well as sinusitis and/or mucocele formation from obstruction of adjacent sinus ostia. This allows decision making and surgical intervention prior to the development of complications, should a lesion increase in size on serial imaging. Whereas small, asymptomatic lesions may be observed, larger, symptomatic tumors should undergo surgical resection. Rapid growth, infection, compression of vital structures, severe pain, facial deformity, vision changes, mucocele formation, and intraorbital and/or intracranial complications are all indications for tumor resection. These include a tumor occupying greater than 50% of the frontal sinus,83 a posteriorly based frontal sinus lesion,87 and any osteoma occupying the frontal recess or ethmoid sinus cavity. Multiple surgical techniques are available for resection of paranasal sinus osteomas. In general, approaches can be divided into three groups: endoscopic, open/external, or combined. Regardless of the approach chosen, the goals of surgery should include complete tumor removal with minimal damage to surrounding mucosa and vital structures. They also recommend that most lesions that are either anteriorly based or located lateral to the sagittal plane of the lamina papyracea should undergo an open osteoplastic procedure. An osteoplastic flap approach via a coronal, brow, or mid-forehead incision, allows for optimal direct visualization of the frontal sinus and its outflow tract. Although such open procedures do have their advantages, the disadvantages are obvious including the increased morbidity of a surgical wound, postoperative pain, scalp paresthesias, visible scars, and possible mucocele formation. Combined endoscopic and osteoplastic flap approaches are often used to gain optimal access to large frontal sinus osteomas. In addition, small frontal trephines may be combined with endoscopic approaches for smaller lesions that do not require a full osteoplastic flap but cannot be managed solely endoscopically. Lesions that are grade 3 and 4 usually require an external approach with or without endoscopic assistance. These complications, of course, includes injury to the orbit, optic nerve, and skull base. Reactive bony hyperplasia may also occur with mucosal injury, leading to obstruction of sinus ostia and subsequent sinusitis. Monostotic lesions (70 to 85%) involve only one bone, while the polyostotic form (15 to 30%) can affect multiple bones. Fibrous dysplasia is usually identified in younger patients, with growth actually decreasing around the age of puberty; because of this, treatment is usually conservative73 with surgical intervention reserved for symptomatic patients or those with cosmetic deformity. Also known as cemento-ossifying fibroma, psammotoid ossifying fibroma, and juvenile-aggressive ossifying fibroma, differentiation from fibrous dysplasia is paramount as their management may differ. While these lesions are most commonly found in the mandible, they are even more aggressive when located in other locations, such as the paranasal sinuses. While most lesions have been resected via external open approaches in the past, endoscopic surgery offers a viable alternative in selected patients. The well-defined borders may allow for a complete endoscopic resection with tumor-free margins. In 1971, Hymans reviewed several hundred cases of this tumor at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; his report aided in solidifying the terminology and pathology of this distinct lesion. Sinonasal papillomas were subdivided into inverted, fungiform, and cylindrical cell types. It is pink to gray in color, with frond-like projections extending from the bulk of the lesion. It should also be noted that when the tumor rests on mucosa not intimately involved in the lesion, the native, uninvolved sinonasal mucosa remains normal. In addition, the orderly maturation of the cells outward from the basal membrane is preserved. The Schneiderian membrane, the embryologic origin of the sinonasal mucous membranes, is at risk for developing this epithelial lesion; therefore the eponym has persisted. Chronic rhinosinusitis has also been proposed as a possible etiologic factor due to a temporal relationship and the increased incidence of sinusitis on the opposite side from the lesion; however, it has also been proposed that chronic sinusitis develops in these patients secondary to the obstructive nature of the neoplasm itself. Presentations are usually unilateral with no side predilection although bilateral lesions do occur in 4. Focal hyperostosis may frequently be seen, often reflecting the point of origin of the tumor. Open approaches such as the lateral rhinotomy and mid-facial degloving procedures allowed for increased tumor visualization and more complete resections with most of these resections usually involving some form of maxillectomy. Since the advent of functional endoscopic sinus surgery in the 1980s, surgeons rapidly developed advanced endoscopic techniques and applied them to the resection of inverted papilloma. Complete resection of the neoplasm requires identification of the site to where it is pedicled to native mucosa.

Safe 2.5mg altace

General indications for surgery are chronic or recurrent infections refractory to medical management prehypertension how to treat order 5mg altace with visa, or hypertrophy of these structures causing obstruction of the aerodigestive tract. Electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, chest x-ray, and intensive care unit admission and cardiology consultation may be required. The tongue is indicated by the up arrow and the epiglottis is indicated by the right arrow. The first-line treatment of adenoid or tonsil hypertrophy is beta-lactamase stable antimicrobials, even if there are no signs of active infection. Chronic subclinical infection of the adenoid and tonsils may respond to a three to four week course of antibiotics and avoid the need for surgery. Parents should be encouraged to observe their child for snoring, restlessness, gasping and pauses, and to use a stopwatch to time any prolonged pauses suggestive of apnea. A polysomnogram is the best test to identify and quantify the presence or absence of apnea and to differentiate between an obstructive and central etiology. Also, a polysomnogram measures sleep disordered breathing on only a single night, and the presence and severity may vary from day to day and change over time. Tonsillar hypertrophy can also cause dysphagia; such can be documented by modified barium swallow study evaluation. Adenotonsillectomy has been shown to improve quality of life on a validated questionnaire, with more children tolerating normal diet and obtaining an increased weight percentile postoperatively. Acute bacterial tonsillitis is characterized by fever, sore throat, odynophagia, malaise, oropharyngeal erythema, edema, and exudates. Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes is the most common bacterial cause, although other bacteria may be present. Rapid strep screening may be helpful, but a negative result does not rule out bacterial tonsillitis. Cultures are helpful to differentiate true streptococcal tonsillitis from viral infections in the setting of chronic and recurrent tonsillitis. Amoxicillin or penicillin is first line therapy, but augmented penicillins, cephalosporins or clindamycin may be required for chronic or recurrent streptococcal tonsillitis. Culture for all pathogens and culture directed antibiotics may be required for refractory cases or tonsil infections in immunocompromised children. Since untreated streptococcal tonsillitis can result in rheumatic fever, scarlet fever or acute glomerulonephritis, treatment with a full course of antibiotics is indicated. Severely affected children with recurrent tonsillitis fulfill indications for tonsillectomy. The landmark randomized, prospective study suggested that a minimum of three documented infections per year for three years, five infections per year for two years, or seven infections in one year are required to show that tonsillectomy resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the frequency and severity of throat infections for two years following surgery. The surgical techniques of tonsillectomy, tonsillotomy and adenoidectomy are further discussed in Chapter 72, "Pediatric Sleep Disordered Breathing. If the patient is unable or unwilling to clean out the crypt debris with cotton-tipped applicators or water irrigation devices, then tonsillectomy may be considered. Viral pharyngotonsillitis and cervical lymphadenopathy may result from viral agents such as adenovirus. Viral infections, like bacterial infections, may also lead to adenotonsillar hypertrophy. These children may have a mild infection similar to a common cold or have a more protracted course with systemic manifestations consistent with infectious mononucleosis. The latter patients may have severe sore throat, adenotonsillar enlargement, airway obstruction, secondary bacterial adenotonsillitis, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, increased atypical lymphocyte count on peripheral blood smear, fatigue, and lightening of the color of stools. Monospot blood test is useful for children over 10 years, but there may be false negatives in younger children. Also as discussed previously, some viruses produce specific constellations of findings in addition to tonsillar inflammation. For example, the Coxsackie virus produces redness, pain and tonsillar enlargement with ulcers and often characteristic lesions on the palms and soles defining hand, foot and mouth disease. Peritonsillar infections are often mixed infections of gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic microorganisms. Broad spectrum antimicrobial agents such as amoxicillin-clavulanate or second generation cephalosporins should be selected for initial therapy. Severe infections will require intravenous antimicrobials such as ampicillin-sulbactam. Peritonsillar cellulitis and abscess can both cause unilateral enlargement of the tonsil and swelling of the soft tissue superior and lateral to the tonsil with medial displacement of the uvula. Peritonsillar cellulitis can often be differentiated from peritonsillar abscess in that abscess is usually associated with trismus but cellulitis is not. Peritonsillar cellulitis, and small early peritonsillar abscesses, will usually respond to medical management, but larger abscesses will require needle aspiration or incision and drainage. The performance of an immediate tonsillectomy as treatment of a peritonsillar abscess is also known as "tonsillectomy a chaud," "quincy tonsillectomy," or "hot tonsillectomy. Additional less frequent indications include concurrent infectious complication such as jugular vein thrombosis or abscess extension to another anatomic location such as the parapharyngeal space. Lemmiere syndrome is a severe complication of tonsillitis characterized by thrombosis of the ipsilateral internal jugular vein secondary to retrograde thrombosis from the tonsillar veins. Treatment includes beta-lactamase stable antibiotics, penicillin plus metronidazole, or clindamycin for three to six weeks or longer. Associated peritonsillar or parapharyngeal spaces abscesses, if present, require drainage. Note normal filling of jugular vein, sigmoid sinus, and transverse sinus on right (arrow) with absence of filling of the same venous structures on left. Although asymmetric tonsillar size may represent malignancy such as lymphoma, the incidence of malignancy in otherwise asymptomatic children without constitutional signs and symptoms is low. Recurrent or chronic pharyngitis can also be caused by supraesophageal reflux of gastric contents. Acidic gastric contents contain pepsin and food materials, both of which are irritating to pharyngeal mucosa. Overeating and excessive drinking are to be avoided, especially before exercise, lying down to sleep, and when the child already has a sore throat or cough. Dietary modifications plus H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors are effective treatments. Amoxicillin is the first-line treatment, with amoxicillin-clavulanate or second or third generation cephalosporins as the second-line treatment. Adenoidectomy is indicated for recurrent or chronic adenoiditis that is refractory to antimicrobial agents. Adenoidectomy is effective to reduce infections from both adenoiditis and sinusitis and may be considered as a surgical option prior to endoscopic sinus surgery. Patients who do not respond to adenoidectomy may still require endoscopic sinus surgery. Histologic examination of adenoid tissue is required for definition of the clinical issue. In particular, children battling cancer are at greater risk for many of the infectious diseases discussed in this chapter. Children undergoing oncologic therapies are at risk for mucositis that can severely affect their already diminished quality of life. The mucositis is important in that it removes a layer of protection, further potentiating the risk for viral, fungal, or bacterial infection of the oral cavity, which can easily become systemic infections in these individuals. Furthermore, xerostomia can occur, removing salivary defense mechanisms and increasing the risk of dental caries and odontogenic infections. Recognizing these limitations of the immune system and innate defenses of children undergoing oncologic treatments will allow careful consideration in the workup and treatment recommendations offered to this subset of patients. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. Identification of Herpesvirus types 1-8 in oral cavity of children/adolescents with chronic renal failure. Epidemiology, clinical presentation and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women.

Generic altace 2.5 mg without a prescription

The clinical value of these tests in diagnosing nonallergic rhinitis is unclear but show promise in monitoring response to treatment cardiac arrhythmia chapter 11 order altace 1.25mg line. Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in further defining masses or other soft tissue lesions. These conditions have different pathophysiologies with the only commonality being a lack of systemic allergic sensitization. There is no widely accepted classification system for the different types of nonallergic rhinitis, but one common classification system is presented in Table 47-1. Patients typically present with thick nasal discharge, nasal congestion, and sneezing which resolves spontaneously in seven to 10 days. Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis can complicate viral rhinitis and lead to persistence of symptoms beyond the usual seven to 10 day course of viral infection Table 47-2). Both acute and chronic rhinosinusitis can be confused with noninfectious perennial rhinitis because many of the symptoms overlap. Middle meatus cultures from adults have been shown to be effective in diagnosing acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Blind cultures of the nasopharynx in children with rhinitis are of little clinical value because pathogenic bacteria have been recovered as normal flora in as many as 92% of asymptomatic healthy children. However skin testing and serum-specific IgE are negative, differentiating this entity from allergic rhinitis. The pathophysiology of this syndrome is not well understood; however, it has been noted to share features with Samter triad (nasal polyposis, aspirin sensitivity, and asthma). The diagnosis of idiopathic rhinitis is one of exclusion and can only be made once all other identifiable causes have been excluded. Symptoms are chronic, primarily of nasal congestion and rhinorrhea, and less likely to include sneezing and itchiness. Nasal cytology does not demonstrate any evidence of inflammation and many have argued that "rhinopathy" may be a more appropriate term than "rhinitis. Both local inflammatory reactions as well as neurogenic mechanisms have been described. In patients with aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease, such as in Samter triad, the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs results in an acute local inflammatory response causing severe rhinitis and asthma symptoms. Antihypertensives, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, psychotropic medications, and oral contraceptives have also been implicated in causing rhinitis. For short periods of time, ie, three to five days, these medications provide significant relief of nasal congestion. However, if used for prolonged periods of time, they can cause rebound nasal congestion which can be severe and refractory to treatment. Patients also develop tachyphylaxis requiring more frequent dosing with less of a decongestive effect. The exact mechanism by 2085 which this occurs is not well understood, but it seems to involve recurrent nasal hypoxia and negative neural feedback with decreased alpha-2 receptor responsiveness. Physical examination typically reveals "beefy red" erythema of the nasal mucosa that is congested and friable. Prolonged use of other topical vasoconstrictive agents, such as cocaine, can also have a similar presentation. Common occupational causes include paint or chemical fumes, wood dust, tobacco smoke, perfumes or fragrances, and hairsprays. Environmental triggers include temperature or pressure changes, animal antigens, and air pollution. The release of neuropeptides from sensory C-fibers in response to irritant exposure is thought to lead to vasodilation and edema. In addition to typical symptoms of nonallergic rhinitis, patients can suffer from decreased sense of smell, crusting, recurrent epistaxis, and reduced mucociliary clearance. Estrogens have been shown to increase hyaluronic acid levels in the nasal mucosa resulting in increased edema and congestion. Increased nasal vascular pooling as a result of increased circulating blood volume and progesterone-induced vasodilation may also contribute to the problem. Beta-estradiol and progesterone have also been shown to increase the number of histamine (H1) receptors in nasal mucosa. Normal ciliated respiratory epithelium is progressively replaced by non-ciliated squamous epithelium resulting in a loss of mucociliary clearance. There is a loss of neuroregulation as well as a decrease in both olfaction and sensation. Patients typically have patulous nasal cavities with crusting, fetor, and epistaxis. While the nasal cavity is widely patent, patients frequently complain of nasal obstruction. This is likely due to changes in airflow pattern, decreased mucus production, decreased sensation and reduction of mucosal surface area. Primary atrophic rhinitis can be the result of aging, heredity, nutritional deficiency, or infection. Early stage infection by Klebsiella ozenae is the most common cause of primary atrophic rhinitis, and is still common in developing countries with warm climates such as India and those in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean area. However, in developed countries, atrophic rhinitis is more 2088 commonly secondary to aggressive surgery, radiation, trauma, cocaine abuse, and granulomatous, eg, sarcoidosis, or infectious, eg, syphilis, rhinoscleroma, diseases. Imaging can also further define soft tissue abnormalities such as nasal polyposis or neoplasms. Granulomatous, autoimmune and infectious diseases, cystic fibrosis, and ciliary dyskinesia can generate symptoms of rhinitis. Patients demonstrate features such as nasal scarring, bleeding, crusting, masses and ulceration, cobblestone appearance of the mucous membrane, and recurrent infections. Treatment is usually geared primarily toward treating the underlying condition with supportive therapies for the nasal symptoms. This should be considered in all cases of refractory rhinorrhea even without a history of surgery or trauma. Testing for beta-2 transferrin within the nasal discharge can help make the diagnosis. Imaging can provide clues to the presence of a skull base defect where the leak may be originating. This idea has arisen from studies that have identified individuals with negative allergy testing who develop nasal symptoms on nasal provocation tests to common allergens. Even in the absence of nasal provocation, some patients have demonstrated the presence of IgE antibodies to allergens to which they locally react. One notable difference, however, is the lack of IgE producing B cells in the nasal mucosa. Further research is still necessary to evaluate the validity and clinical significance of these findings, but they raise interesting questions for the future of diagnosis and management of many patients who may be incorrectly diagnosed as having idiopathic rhinitis. Treatment varies by cause, and identifying the specific subtype of rhinitis from which a patient through careful history, examination, and diagnostic testing can help devise an appropriate treatment plan. Several treatment options for nonallergic rhinitis are reviewed here, a combination of which may be necessary to control the patient symptoms. Regardless of treatment regimen, patient education is a critical component of the treatment plan and allows the patient to play an active role in their care. Environmental Control Patients with known environmental, occupational, or other inhaled irritant triggers should be advised to try to avoid exposure. Avoiding certain factors such as tobacco smoke, perfumes or fragrances, chemicals, and certain foods can be accomplished rather easily. When avoidance is not possible, pharmacologic therapies may be necessary to help control symptoms. This class of medication treats the broadest spectrum of symptoms and seems to be effective to some degree in all forms of rhinitis. Corticosteroid nasal sprays treat inflammation regardless of cause and have been proven to have broad safety profiles. Local side effects are infrequent and include nasal dryness, epistaxis, sore throat, and headache. Studies have shown mixed results with the use of mometasone for nonallergic rhinitis. All formulations are pregnancy category C with the exception of budesonide, which is pregnancy category B and has been shown to be effective in nonallergic rhinitis. The nasal cavity should be free 2091 of obstructions, either anatomic or pathologic, so that the medication can reach its intended target.

Order discount altace on-line

The masseter muscle attaches to the lateral aspect of the mandibular angle and ramus blood pressure 200120 buy altace american express, and the medial pterygoid muscle attaches on the medial surface of the angle and ramus. Other muscles that attach to 2905 the mandible are the genioglossus (mental spine), geniohyoid (mental spine), mylohyoid (at the mylohyoid line), and the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles (digastric fossa). The other important marking on the mandible is the mental foramen, which is located between the second and third premolar interspace. This foramen is where the mental nerve exits, carrying afferent nerve fibers from the chin and lower lip. Prior to it becoming the mental nerve, it is also known as inferior alveolar nerve as it courses through the mandibular canal with the inferior alveolar vessels. The motor innervation to the muscles of mastication is via the mandibular nerve branch of the trigeminal nerve. The sensory innervation to the mandibular teeth is carried by afferent nerve fibers from the inferior alveolar nerve, likewise a branch of the mandibular nerve. The blood supply to the mandible is primarily from the lingual, facial, and inferior alveolar arteries which are branches of the internal maxillary artery. The major arterial supply to the mandible is from the inferior alveolar artery which gives off branches referred to as periosteal arteries. The lymphatic drainage from the body, angle and symphysis of the mandible is to the submandibular lymph nodes. The retromolar trigone is bounded by the distal surface of the third or last remaining mandibular and maxillary molars anteriorly, and the ramus of the mandible to the coronoid posteriorly, with its apex at the maxillary tuberosity. The lateral aspect of this space is contiguous with the gingivobucccal sulcus, and the medial aspect is the anterior tonsillar pillar. Blood supply to the retromolar trigone is the tonsillar and ascending palatine branches of the facial artery. The lymphatic drainage is primarily to the upper deep jugular lymph node chain, with some drainage to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes. The borders of the palatine tonsils are the palatoglossus muscles anteriorly and the palatopharyngeus muscles posteriorly. The lateral border of the tonsillar fossa is the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, with 2907 the superior border being the soft palate extending inferiorly to the base of tongue. The palatine tonsils are aggregates of lymphoid tissue which along with the lingual tonsils and the pharyngeal tonsil (adenoid), comprise the Waldeyer ring. The sensory innervation to the palatine tonsils is from the sphenopalatine ganglion and the glossopharyngeal nerve. The soft palate is composed of several muscles that aid in its function of speech production and swallowing. These muscles include the levator veli palatini, tensor veli palatini, musculus uvulae, palatoglossus, and palatopharyngeus. The levator veli palatini and tensor veli palatini are involved in elevating the soft palate during swallowing. The musculus uvulae is responsible for the shape and movement of the uvula, the palatoglossus elevates the posterior part of the tongue and closes the oropharynx, and the palatopharyngeus elevates the pharynx. The motor innervation to the soft palate is primarily from the pharyngeal plexus which is supplied by the vagus nerve; however, the tensor veli palatine muscles receive motor innervation from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve. Sensory fibers from the soft palate are carried by the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve. The soft palate receives its principal blood supply from ascending palatine artery and its venous drainage is via the pharyngeal plexus. The base of tongue, also referred to as the posterior one-third of the tongue, is defined anteriorly by the circumvallate papillae and extends inferiorly to the level of the valleculae. The intrinsic and extrinsic tongue musculature was previously described in detail in the oral cavity section. The hypoglossal nerve provides motor innervation to the base of tongue musculature. Sensation from the majority of the base of the tongue is from the glossopharyngeal nerve. The most inferior aspect at the vallecula receives sensory fibers from the superior laryngeal nerve. The base of tongue receives its blood supply from the dorsal lingual artery which is a branch of the lingual artery; its venous drainage is via the dorsal lingual vein. The pharyngeal wall is composed of four layers; there is an inner mucosal layer, fibrous layer consisting of the pharyngobasilar fascia, a muscular layer made up of the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictors and a fascia layer, the buccopharyngeal fascia, which covers the outer layer of the muscles. Along the lateral aspect of the oropharynx, the muscular layer is also comprised of the stylopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus muscles. The sensation of the posterior pharyngeal wall is via the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the motor innervation of the middle and inferior constrictor muscles is via the pharyngeal plexus from the vagus nerve. The palatopharyngeus and salpingopharyngeus muscles are innervated by the vagus nerve, but the stylopharyngeus muscle is innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve. The posterior wall of the pharynx is supplied by the ascending pharyngeal and inferior thyroid arteries. Venous drainage of the posterior pharyngeal wall is via the pharyngeal plexus which ultimately drains to the internal jugular vein. The lymphatic drainage from the posterior pharyngeal wall may be either to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes or to the deep cervical lymph nodes. The valleculae are the right and left areas between the root of the base of tongue and the epiglottis. The valleculae are divided into a right and left by the median glossoepiglottic fold. Sensation of a vallecula is via the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The blood supply is from the lingual artery, and venous drainage is via the lingual vein. Lymphatic drainage from a vallecula is primarily to the deep cervical lymph nodes of the neck; which may be bilateral. They are located in the preauricular region extending along the posterior surface of the mandible. The parotid glands extend superiorly to the zygomatic arch and inferiorly to overlay the superior portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Each parotid gland has a ductal communication with the oral cavity (Stensen duct), the orifice of which lies within the buccal mucosa opposite the second maxillary molar. From a neural innervation standpoint, the glossopharyngeal nerve provides preganglionic parasympathetic fibers via the lesser petrosal nerve to the otic ganglion; the postsynaptic parasympathetic fibers to the parotid gland are carried in the auriculotemporal nerve to the parotid gland and regulate salivary production. The blood supply to the parotid gland is from branches of the external carotid artery, particularly the transverse facial artery, which is a branch of the superficial temporal artery. The venous drainage of the parotid gland is through the retromandibular vein, which drains into either the external or internal jugular vein. Although there are both superficial and deep lymph nodes, the vast majority are within the superficial portion of the gland. Submandibular Glands the paired submandibular glands lie within the submandibular triangle defined by the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscles and the inferior aspect of the mandible. The majority of the submandibular gland lies lateral to the mylohyoid muscle, but a small portion wraps around the posterior edge of the mylohyoid on its medial aspect. The saliva of the submandibular glands enters the oral cavity via Wharton ducts which enter the floor of mouth just off the midline. The lingual nerve carries presynaptic parasympathetic fibers to the submandibular ganglion, from which postsynaptic fibers leave the ganglion and innervate both the submandibular and sublingual glands. The lymphatic drainage from the submandibular glands is to the perifacial nodes that lie in close approximation to the facial artery, which drain into the deep cervical lymph 2911 nodes. Sublingual Glands the sublingual glands are the smallest of the major salivary glands. They lie caudal to the mylohyoid muscle in the floor of mouth on either side of the lingual frenulum. The saliva of the sublingual glands enters the oral cavity through the ducts of Rivinus on the superior aspect of the gland or the Wharton duct via the Bartolin duct.

Buy altace 10mg amex

A comparison of intranasal corticosteroid blood pressure chart software trusted 2.5mg altace, leukotriene receptor antagonist, and topical antihistamine in reducing symptoms of perennial allergic rhinitis as assessed through the rhinitis severity score. Leukotriene receptor antagonists for allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Comparison of montelukast and pseudoephedrine in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Montelukast plus cetirizine in the prophylactic treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis: Influence on clinical symptoms and nasal allergic inflammation. Randomized placebocontrolled trial comparing fluticasone aqueous nasal spray in monotherapy, fluticasone plus cetirizine, fluticasone plus montelukast and cetirizine plus montelukast for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Effect of the addition of montelukast to fluticasone propionate for the treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis. Histamine and leukotriene receptor antagonism in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: an update. Clinical studies of combination montelukast and loratadine in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Comparison of a nasal glucocorticoid, antileukotriene, and a combination of antileukotriene and antihistamine in the treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose loratadine/montelukast in seasonal allergic rhinitis: effects on nasal congestion. Effect of anti-immunoglobulin E on nasal inflammation in patients with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. The anti-inflammatory effects of omalizumab confirm the central role of IgE in allergic inflammation. Relationship between pretreatment specific IgE and the response to omalizumab therapy. Allergen skin tests and free IgE levels during reduction and cessation of omalizumab therapy. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in the treatment of adults and adolescents with perennial allergic rhinitis. Omalizumab pretreatment decreases acute reactions after rush immunotherapy for ragweed-induced seasonal allergic rhinitis. A review of pregnancy outcomes after exposure to orally inhaled or intranasal budesonide. A comprehensive overview of allergic rhinitis is presented in Chapter 43, "Allergic Rhinitis. Likewise, the paratope is the portion of the host antibody that recognizes the epitope on an antigen. Epitopes and paratopes fit together precisely and may initiate a cascade of immunological events that eventually lead to the release of IgE and other immune mediators involved in the allergic response. However, it should be noted that epitopes may cross-react between different antigens, and the cross-reactions can even occur between inhalant and food antigens. Pollens, or the male germinal cells in plant reproduction, comprise the majority of outdoor allergens, typically range in size from 6 to 100 m, and can be divided into two main subgroups. Entomophilous pollens are those distributed by insects and are often too large and adherent to cause allergy. Conversely, anemophilous pollens are lighter and smaller than their entomophilous counterparts, are dispersed by the wind and tend to be more responsible for allergic disease. Pollen-producing plants can be classified into two major groups, the gymnosperms and the angiosperms. Gynmosperm species include those plant species in which the ovules are carried naked on scales of a cone and include now-flowering trees, such as ginko and conifer species, such as members of the cypress and pine families, which produce thin leaves, needles, and cones. As a subclass of pollen-producing plants, gymnosperms in general have the greatest diversity and least antigenic cross-reactivity of all pollen producers. Therefore, although their airborne pollens are copious, they are typically not very potent. However, an exception to this rule is the cypress family (Cupressacae), which 2015 produces potent pollens that share major cross-reactivity within the family. Angiosperm species are those plants in which the sex organs exist within flowers and their seeds exist within fruit, such as grasses, weeds, and flowering trees. As a group, angiosperm trees are the most diverse, but least cross-reacting plant species, and usually only have strong cross-reactions within each genus. However, some family cross-reactions do exist, including cross-reactions not only between members of the same family, such as birch trees with alder, hazel, and beech trees, but also between members of other families, such as birch with ash or olive trees. Without question, grass pollens are by far the most potent allergens of the angiosperm plants, with 20 to 50 identified allergens and 10 allergen groups and with strong cross-reactivity both within and between grass families but also with some foods. In the case of treating grass pollen allergy, it is critical to control allergen load in addition to other pharmacologic and immune-modulating therapies. The most common grasses are divided into five subfamilies: pooideae, cloridoideae, panicoideae, arundonoideae, and bambusoideae. The pooideae subfamily encompasses the most familiar cultivated and wild grasses worldwide and includes Timothy and Kentucky blue grasses, and most cereals, such as barley, oats, rye, and wheat. Strong cross-reactions with the subfamily exist, and Timothy grass pollen appears to contain all of the antigenic epitopes for the subfamily. The cloridoideae subfamily includes Bermuda grasses and others similar grasses found in the plains and subtropic regions, whereas the panicoideae subfamily includes crabgrass and edible grasses such as maize, millet, and sugarcane. Weed allergens can be broken down into composites, which include three large tribes of common wind-pollinating and highly allergenic weeds, and chenopods/amaranths, which are two related allergenic weed families. While other weeds may be of local importance in a specific geographical area, these 2016 two aforementioned subgroups are of major importance in North America. The composites are further broken down into the heliantheae tribe, which includes ragweed, the anthemideae tribe, which includes sage and dandelion but partly cross-reacts with ragweed,6 and the astereae tribe, which includes daisy and goldenrod. Ragweed is the most important weed allergen in North America and has significant cross-reactivity within its subfamily, which includes false, giant, short, and western ragweeds. Pollination, and hence the allergy season, occurs in a predictable annual pattern for different regions of the country, but this pattern varies throughout the country. In the Northeast, trees pollinate in mid-March to late April, grasses follow in May and June, and ragweed flowers from mid-August until the first frost. In contrast to the sharply demarcated grass season that occurs in the north, grasses may pollinate from March through September in the south, and in some areas, pollination may be a year-round process. The pattern in the central United States resembles the patterns seen on the East coast. In the California lowlands, grass pollen is present from early March through November, and trees and short ragweed are present as in other regions. However, mugwort has 80% crossreactivity with ragweed and is the most prevalent in California and many parts of Europe, so it should not be overlooked in these areas. Global climate changes, driven by the increased concentrations of gases such as carbon dioxide, have been shown to stimulate opportunistic weeds and trees including ragweed, maples, birches, and poplars to produce more pollens. The increase in temperature also encourages growth of molds and fungi, which may result in important allergen loads for individuals who have asthma and allergic rhinitis. Dust mites are microscopic, eight-legged organisms of the genus Dermatophagoides, including D. They are the major allergens in "house dust," and are found throughout the world, with the exception of regions with extremely dry climates such as northern Sweden, central Canada, and areas at an elevated altitude, such as Denver, Colorado. Typical household bedding, upholstered furniture, carpets, and stuffed toys provide an ideal environment for proliferation and accumulation of dust mites. Unlike outdoor pollens, the antigens contained in dust mite feces, which are the source of the allergen, are relatively large particles that remain airborne for short periods of time. When an individual sits on a bed, the particles become airborne and are inhaled, but because these particles are large, they settle from the air rapidly, and air filtration systems cannot effectively remove them. Lowering the indoor relative humidity to less than 50% during the summer months had a profound effect on the mite population and the antigen load throughout the year, suggesting a role for dehumidifiers even in homes with central air conditioning. Cat and dog dander are the most frequent, but mice, guinea pigs, and horses can all be responsible for allergic symptoms.

Order altace

Anterior to the basal lamella of the middle turbinate arteria iliaca comun buy genuine altace line, the cells drain through the middle meatus. It shares a common superior insertion onto the skull base with the middle turbinate. The posterior ethmoid cells drain into the superior meatus, which is the space between the basal lamella of the superior turbinate and the basal lamella of the middle turbinate. The ostium of the sphenoid sinus lies medial to the superior turbinate within the sphenoethmoidal recess. The infraorbital nerve traverses along the roof of the maxillary sinus and exits through the infraorbital foramen roughly 6 to 7 mm below the inferior orbital rim. Behind the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus lies the pterygomaxillary fossa, which contains the internal maxillary artery and its branches, sphenopalatine ganglion, the vidian nerve, the greater palatine nerve, and the second branch of the trigeminal nerve, originating from foramen rotundum. The floor of the maxillary sinus is formed by the alveolar process of the maxilla. The bone covering the roots of the molar teeth may occasionally be dehiscent in the floor of the sinus. The natural maxillary ostium is the anatomic merging point for mucociliary transport from the maxillary sinus. The maxillary ostium is located at the anteromedial aspect of the sinus near the roof of the sinus. The maxillary ostium opens into the ethmoid infundibulum, lateral to the lower onethird of the uncinate process. The natural ostium is typically elliptical in shape, and rests about 2 mm posterior to the anterior most insertion of the uncinate process. Two bony dehiscences, the anterior and posterior fontanelles, may exist along the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. These fontanelles are 1694 usually covered by mucosa but in some individuals may be patent, thereby forming an "accessory ostium. Infraorbital ethmoid cells occur when an ethmoid air cell pneumatizes inferolaterally along the orbital floor into the maxillary sinus. A large infraorbital ethmoid cell may encroach upon the maxillary ostium and narrow the ethmoid infundibulum thereby predisposing patients to maxillary sinus obstruction. This is the most frequent anatomical variation in the maxillary sinuses, first described by Haller in 1765. Haller cells are thought to arise predominantly from the anterior ethmoid sinus (88%) but they may also arise from the posterior ethmoid (12%). Frontal Sinuses the frontal sinus is formed by pneumatization of the ethmoid labyrinth superiorly into the frontal bone. The sinus drains at its inferior and medial extent, 1695 with secretions descending from the frontal infundibulum through the frontal ostium and frontal recess into the middle meatus. The term "nasofrontal duct" should be avoided when referring to the drainage pathway below the frontal ostium as it is not a true duct. The frontal recess is instead a variable outflow tract whose configuration is defined by the orientation of the uncinate process, ethmoid bulla, agger nasi, frontal cells and supraorbital ethmoid cells. Suprabullar cells or the suprabullar recess may alternatively define the posterior border of the frontal recess. Frontal cells and supraorbital ethmoid cells are properly categorized as part of the anterior ethmoid labyrinth. However, because of their proximity to the frontal ostium, they can affect frontal sinus outflow and are considered part of the frontal recess anatomy. Frontal cells are anterior ethmoid cells that contact the frontal bone and are layered superior to the agger nasi. Supraorbital ethmoid cells result from pneumatization of the orbital plate of the frontal bone. Present in up to 62% of individuals, these cells are located lateral and inferior to the frontal sinus proper. These cells can be capacious and can be mistaken for the frontal sinus during endoscopic surgery. The frontal inter-sinus septum may itself also pneumatize, resulting in an intersinus septal cell which drains into either the right or left frontal recess. The planum sphenoidale refers to the roof of the sphenoid sinus, which forms the skull base, while the sphenoid rostrum refers to the bony anterior face of the sphenoid sinus. The sphenoid rostrum articulates anteriorly with the vomer bone of the nasal septum. The sphenoid sinus drains anterosuperiorly through its own ostium which lies within the sphenoethmoidal recess between the superior turbinate and posterior aspect of the nasal septum, 10 to 15 mm superior to the bony choana. The sphenoid intersinus septum often away from the midline, creating asymmetrical sinuses and potentially abutting the optic and carotid canals. Other important structures that are intimately related to the sphenoid sinus include the Vidian nerve, the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (V2) at the foramen rotundum, the cavernous sinus and the pituitary gland. Note how these cells have narrowed the natural outflow tract of the maxillary sinuses resulting in bilateral maxillary sinus disease. In 20 to 50% of individuals, the sphenoid bone may be partially pneumatized by a posterior ethmoid cell resulting in a sphenoethmoidal or Onodi cell. Despite occupying space within the sphenoid sinus, the sphenoethmoidal cell has an ethmoid origin. Failure to recognize the presence of a sphenoethmoidal cell could result in inadvertent injury to the optic nerve or carotid artery during posterior ethmoid sinus surgery. The term sphenoethmoidal cell is a more descriptive and anatomically accurate term and is preferred to the eponym. Development of the paranasal sinuses in children: implications for paranasal sinus surgery. The cartilaginous nasal capsule and embryonic development of human paranasal sinuses. The postnatal development of the sphenoidal sinus and its spread into the dorsum sellae and posterior clinoid processes. Lateral lamella of the cribriform plate: software-enabled computed tomographic analysis and its clinical relevance in skull base surgery. Computed tomographic and anatomical analysis of the basal lamellas in the ethmoid sinus. The senses of taste and smell largely determine the flavor of foods and beverages and provide a sensitive and early means for detecting dangerous environmental situations, including the presence of fire, spoiled food, and leaking natural gas. These senses are important to otorhinolaryngologists as (a) their stewardship falls within the purview of their specialty, (b) some otorhinolaryngologic operative procedures compromise the functioning of these senses, (c) alterations in chemosensory function can be an early sign of a number of diseases, including Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease, and (d) losses or distortions of chemosensation are of considerable personal and practical significance to the patient. The latter should not be underestimated and is particularly acute for patients whose lifestyle, livelihood, or immediate safety depend upon smelling and tasting (eg, cooks, firemen, homemakers, plumbers, professional food and beverage tasters, employees of natural gas works, chemists, and numerous industrial workers). In one study of 445 persons presenting to a chemosensory disorders clinic, at least one hazardous event (eg, food poisoning or failure to detect fire or leaking natural gas) was reported by 45. Common chemosensory disorders and the means for quantitatively assessing, managing, and treating patients with these disorders are discussed. Although it reportedly comprises ~ 2 cm2 of the upper recesses of each nasal chamber, it is not a homogenous structure, as metaplastic islands of respiratory-like epithelium accumulate within its borders beginning early in life, presumably as a result of insults from viruses, bacterial agents, and toxins. The cilia of these cells, which extend into the mucus of the nasal lumen, harbor the olfactory receptors. The sustentacular cells insulate the receptor cells from one another and extend microvilli, rather than cilia, into the mucus. These cells contribute to the mucus of the region and may be involved to some degree in deactivating odorants and xenobiotic agents. The function of the ~600,000 microvillar cells located at the epithelial surface is unknown. While, under normal circumstances, periodic replacement of cells occurs within basal segments of the epithelium, many receptor cells are relatively long lived and appear to be replaced only after they are damaged. Four cell types are indicated: ciliated olfactory receptors (c), microvillar cells (m), supporting cells (s), and basal cells (b). The receptor cell axons of the olfactory nerve layer enter the glomeruli within the second layer of the bulb, where they synapse with the dendrites of the mitral and tufted cells within the spherical glomeruli. Indeed, mitral cells modulate their own output by activating granule cells (which are inhibitory to them).