Generic gasex 100 caps without prescription

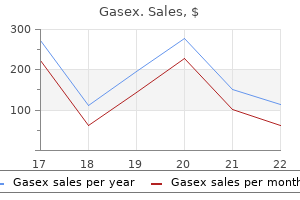

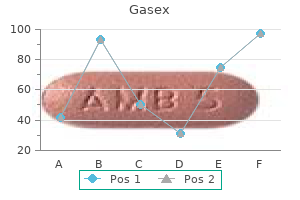

When mixing gastritis symptoms when pregnancy discount 100caps gasex with visa, whoever is performing the preparation of dilutions, treatment board, or patient treatment vials should do so in a quiet place where he/she will not be disturbed. Expiration dates should be clearly visible on all vials, including the dilution vials used for the treatment board and individual patient treatment vials. The different colored vials represent different concentrations of antigen, with the blue vials representing #1 dilutions (most concentrated) and purple vials representing #6 dilutions (most dilute). A log should be kept in each chart with the escalation or maintenance schedule, checked off as each injection is received with documentation of any adverse reactions for prior injections. In addition, a vial test should be performed whenever a patient is receiving the first injection from a newly mixed vial where either the allergy test results (and thus, the vial mixing recipes) were based off serum specific IgE testing or a different antigen lot number was used in the patient vial recipe than was used either for previous testing or treatment. It is a safety screening measure that may help the practitioner determine if it is safe to administer injections to the patient from the vial in question or avoid injecting a patient with a mix that is too concentrated and likely to cause a severe reaction. The vial test in this case is a verification that the predetermined dosage calculated from the serum specific IgE test results is likely to be safely tolerated by the patient. The vial test serves to ensure that if the concentration or potency of the antigen does vary between lots, the patient will safely tolerate a vial mixed with antigen from the new lot. Expert opinion varies on whether or not a vial test is necessary for each and every new vial, with some experts suggesting that vial tests are not necessary with vials mixed from the same lot number or even from skin testing results. However, it is the opinion of the author that each and every new vial, regardless of test method, lot, or phase of treatment, should be vial tested prior to the first patient injection. The extra time involved is minimal when compared with the potential benefits of avoiding a severe or anaphylactic reaction. In addition, this is a great option for children and patients that are needle phobic or cannot tolerate injections. Sublingual administration of allergen extracts has been shown to be a well-tolerated and efficacious approach to treating allergic rhinitis. Reports on the safety and efficacy of this treatment have grown enormously in the last five to 10 years. Whereas the first generation of sublingual vaccines used today are based on natural biological extracts, new vaccines that rely upon selected recombinant allergens are being developed. Patient education is important to the success of this therapy, as clear instructions to the patient regarding how to perform the therapy are needed. This includes not only reviewing the dosing protocol with the patient as to how many drops from which vial should be administered on a specific day, but also how to actually self-administer or administer to a child or other person the dose. Patients need to be educated that the allergen is to be kept under the tongue for roughly two minutes and then swallowed. Without this information, patients tend to put the drops in their mouth and swallow, without waiting the necessary two minutes. If the vaccine is swallowed immediately, the clinical efficacy decreases substantially. However, considerations should still be given to what other medical conditions the patient has should a serious adverse reaction, such as anaphylaxis occur. Patients with asthma must be well-controlled and control reassessed at each immunotherapy visit. If a patient should become pregnant during escalation, the current dosage and its likely effectiveness should be assessed. Beta blockade tends to make more serious adverse reactions, like anaphylaxis, much more difficult to treat, since these reactions become more resistant and less responsive to epinephrine. However, most of these protocols do not adjust any dosing calculations based on the sensitivity of the patient to particular antigens. The literature has yet to demonstrate conclusively which modality is more effective; both therapies have been demonstrated to be efficacious, with reduction in symptom and medication scores, but without a clinically significant greater improvement in one therapy demonstrated over the other. It is important to investigate which local flora, and possibly fauna, are present so that appropriate antigens are used in testing. Once a patient has been tested, regardless of method, these results are used to formulate an immunotherapy treatment vial specific to the antigens to which the patient is sensitive. A question faced by practitioners, particularly in patients with multiple positive tests, is whether or not to treat for each and every single positive antigen test. The answer to the question has not been convincingly addressed, and practitioners tend to fall into two main "philosophical" schools of thought. This is not to imply that these viewpoints are not supported by evidence; on the contrary, there are published studies to support both sides, and thus, at this point in time, endorsing one side over the other comes down to expert opinion. The therapeutic dilemma is faced regardless of the type of immunotherapy the patient receives. Yet, many patients in the United States are polysensitized, so the question is "to treat or not to treat Thus, immunotherapy for one specific antigen stimulates alterations in the immune system that allow for the development of tolerance, or reduced sensitivity, to other, nonspecifically treated antigens. This style of practice is most commonly encountered in Europe and the United Kingdom. Allergists that follow this treatment style select one or at most, a very few, select antigens that they feel are the "most prominent offenders" and perform immunotherapy. For example, some practitioners, such as some in Europe, will not combine antigens in a single vial or injection. If more than one antigen is selected, for example, cat and birch pollen, the two antigens are not mixed in a single treatment vial nor given in a single injection. Each antigen is kept separate and two separate shots are administered in two separate areas of the body. Other practitioners who may follow the "pauci" method will combine the few select antigens for treatment into a single vial to be administered in one injection. There is no evidence to support the use of one type or style of this technique over the other. Evidence in favor of this particular style of therapy is the fact that the vast majority of clinical immunotherapy trials have been with single allergens and the majority of these trials have demonstrated effectiveness. Thus, immunotherapy for one specific antigen will not successfully allow for the development of tolerance to another, nonspecifically treated antigen. It will only allow for tolerance to develop to that specific antigen and antigens that closely cross-react with it. Allergists that follow this treatment style will generally treat most or almost all antigens that have positive test results. The practice of multi-antigen therapy is most commonly used by allergy practitioners in the United States. Ideally, a single injection is given but as will be discussed shortly, at times it is better to separate certain antigens from others, so this may necessitate multiple injections. The number of studies that have investigated the effectiveness of multi-allergen immunotherapy have been limited and have produced some conflicting results. Further research on the efficacy of multi-allergen immunotherapy is needed, as well as the efficacy of mono/pauci therapy on untreated antigen sensitivities. So the question remains for those of the "multi" antigen school of thought, "is it really necessary to treat each and every positive test Certain antigens can be mixed together without loss of potency while there is evidence that others cannot. Some antigens contain proteolytic enzymes that will degrade the protein components of other aeroallergens. These types of enzymes are present in some mold extracts and could digest other antigens, such as pollens or dust mites,thus reducing their potency when combined in a mixture. Still, consideration should be given to separating pollen and other extracts from extracts with high proteolytic activity when using multi-antigen therapy. One further consideration for those treating with multiple antigens is the concentration of glycerin in the patient treatment vial. The potency of each antigen will vary depending on the concentration of glycerin in the preparation, with aqueous formulations having the shortest duration of potency and antigen formulations in 50% glycerin maintaining potency for the longest duration. The higher the concentration of glycerin in the immunotherapy injection, the more painful the injection is to the patient, so a balance must be achieved between formulating a vial with enough glycerin to preserve antigenic potency and not so much that the pain of injection is a deterrence to continuation of treatment. In general, a concentration of 10% glycerin is recommended as a way to achieve this balance.

Buy gasex without prescription

Visualization of the facial nerve as a landmark permits the opening of the atresia plate to approximate the size of a normal middle ear opening gastritis x helicobacter pylori buy discount gasex 100caps on-line. While drilling on this plate, it must be remembered that the malleus handle most often is fused to it. Options for ossicular reconstruction include mobilization of the intact ossicular chain, and partial or total ossiculoplasty using either an autologous or commercially available prostheses. Several excellent series compare ossiculoplasty techniques to intact ossicular chain reconstruction. One group found that children who underwent ossiculoplasty techniques (either partial or total) had an increase in the air-bone gap closure and improvement in speech reception threshold. A meatal opening is made in the area of the imperforate concha, incising the skin to create a rectangular-shaped anteriorly based conchal skin flap. The underlying cartilage and soft tissue are removed to debulk the flap and create an opening that communicates with the drilled out external canal. The conchal flap can be rotated to resurface the anterior third of the external canal; it is stabilized by suturing it to the adjacent soft tissues. A thin split-thickness skin graft is harvested either freehand from the groin area or from the posterior aspect of the thigh or the arm using a dermatome. The suture line is sewn on a bias such that it allows side to side as well as longitudinal expansion of the graft, therefore allowing it to be adjusted to custom fit within the bony canal. Currently, active middle ear and bone conduction implants are utilized under experimental paradigms at our institution. The algorithm applies for both unilateral and bilateral atresia; however, hearing management is a requirement in bilateral atresia and an option in unilateral atresia. This pack is typically removed after two weeks, and an additional smaller pack is reinserted for an additional two weeks. At four weeks postsurgery, a clinical decision is made to or not to proceed with further packing. The child is then followed closely; and, at any sign of decreasing canal caliber, packing is resumed. Atresia surgery is technically demanding, and the outcome appears to correlate with surgical experience. The outcomes following atresia repair reported in the literature are variable in terms of overall audiologic outcome and longterm stability. More commonly, although improvements in hearing and reduction of the air-bone gap are achieved, air conduction hearing often remains abnormal, requiring or benefiting from amplification. What is consistent across all reported series is that hearing results tend to degrade over time with a relatively high revision rate of 16 to 34%. Thus, even in patients with bilateral atresia in whom the facial nerve obstructs the oval window or hearing improvement cannot be achieved, providing the patient with a stable skin-lined canal can be a worthy goal in and of itself. Coincidentally, the number, quality and durability of implantable hearing aids have increased. The surgery to implant them is reasonably straightforward and will be discussed in the following sections. A reliable hearing restorative technique for external auditory canal atresia is the placement of a percutaneous abutment retained bone conduction hearing aid (Table 68-5). In adults, placement of the implant and abutment complex is usually performed as a one-stage procedure. In young children, however, a two-stage procedure is often employed due to the reduced thickness of the calvaria. For these devices the fidelity of sound transmission depends on the thickness of the intervening soft tissue. This cosmetically appealing option does carry the risk of skin breakdown and discomfort at the magnet site. Previous transcutaneous magnet devices existed but unfortunately led to soft tissue breakdown and did not produce adequate fidelity of sound transmission. The current design of the new-generation devices are said to improve sound quality with reduced complications. The main potential complications of such devices relate still to soft tissue irritation, pain and breakdown. A large series (n>100) with long-term follow-up (> 5 years) demonstrated a 4% risk of temporary pressure marks which were relieved by alterations in the magnetic force applied (ie, application of a weaker magnet). Given that current indications for this device are for patients 18 years and older, the pediatric experience is limited. This is followed by typically a six to nine month period to allow for adequate osseointegration prior to the second stage application of the percutaneous abutment. At our institution, every child receives a second "sleeper" implant (ie, two implants are placed for osseointegration at the same time, but only one is fitted with an abutment). The second implant is available for its future use should the first implant, ever extrude, fail to osseointegrate or be damaged by trauma. The hearing result with these devices is superior and more consistent compared to atresia repair. There are currently no published reports of audiometric outcomes and complications to date for these devices. This technology was initially introduced in 1996 and a number of reports exist outlining its use in older children with atresia. Device is fixed on stapes capitulum and sandwiched in placed by the distal incus (white *). It can be an attractive option following a failed atresia repair as it has the capacity to aid the high frequency sensorineural component that may accompany previous repair as a result of high speed drilling or other manipulation of the ossicular chain. Given the ability to use a round window fitting, this device technically could be used for children with lower Jarsdoerfer scores (eg, < 8); however, as the Jarsdoerfer score decreases, the approach to the middle ear becomes more difficult with a higher potential rate of complication. Therefore, consideration on an individualized level is required in such situations. Early reports on audiometric outcomes demonstrate significant improvements in pure-tone threshold and speech understanding at the time of device activation that remained stable up to 48 months without any evidence of device extrusion or surgical complication. Ossicular fixation can be produced by a variety of abnormalities and may involve any portion of the ossicular chain. Alternatively, there may be a failure of development leading to ossicular discontinuity, most commonly involving the incus or stapes arch. Between these two extremes is an array of anomalies with variable surgical outcomes and durability of the repair. Before assuming this responsibility, especially in children, the otologic surgeon must have sufficient experience to maximize the likelihood of a successful outcome. Isolated ossicular malformations involving the stapes arch and long process of the incus may or may not be appreciated on imaging studies. In these cases, the middle ear can be explored by elevating a tympanomeatal flap and assessing the normalcy of the ossicular transduction mechanism. Depending on the size of the external auditory canal and the experience of the surgeon, middle-ear exploration can be performed using a transcanal, endaural, endoscopic or postauricular approach. Upon entering the middle ear, the continuity and fixation of the ossicular chain is assessed. If indeed the chain is fixed, then the cause of the fixation needs to be identified (Table 68-6). First, the mobility of the incus and malleus can be determined through a sequence of intraoperative assessments. Does drilling away the bone over the malleus head and body of the incus provide the required exposure to explore this area If the stapes is fixed, mobilization may produce a sustained improvement; alternatively, a stapedectomy using a replacement prosthesis with an oval window tissue graft to prevent a perilymphatic leak may be performed. A gap interrupting the continuity of the ossicular chain occurs most commonly at the incudostapedial joint, owing to absence of the lenticular process, long process of the incus or the stapes arch. The presence of a mobile stapes facilitates the surgery and is a positive predictor for good postoperative audiometric outcome. A variety of techniques have proven useful in the restoration of ossicular chain continuity by means of bridging an existing gap.

Buy gasex with visa

After dilating the stenotic segment gastritis diet 444 discount gasex 100 caps mastercard, a stent made from an endotracheal tube can be inserted and left in position for up to 8 weeks. The most posterior aspect of the bony nasal airway is the paired nasal choanae which connect the nasal cavity to the nasopharynx. Choanal atresia was described as early as 1755 by Roederer who was actually quoted by Otto in 1829 in his treatise regarding a curious post mortem. Choanal atresia is estimated to affect every 1/5000 to 1/8000 live births, and can occur unilaterally as well as bilaterally. The exact incidence of choanal stenosis is more elusive as such may only cause mild symptoms in some cases. Brown and colleague demonstrated that a mixed bony-membranous atresia occurs 71% of the time with the remainder being a purely bony atresia. Some of these isolated cases have been linked to endocrine dysfunction as a result of in utero exposure to methimazole, retinoic acid suppressors, and certain herbicides. From an anatomic standpoint, choanal atresia does not simply involve a bony or membranous plate at the end of the nasal cavity. Rather, it is a developmental narrowing of the posterior nasal cavity that involves varying degrees of lateralization of the vomer and medialization of the posterolateral nasal wall and ptyerigoid plates. Two prominent theories exist with respect to the embryologic derivation of choanal atresia, one invoking anomalous neural crest cell development, and the other considering it to represent a foregut developmental anomaly with imperforation of embryologic mesoderm separating the developing nasal cavity and pharynx. In bilateral choanal atresia, a neonate will present with the signs of paradoxical respiratory distress due to obligate nasal breathing. Failure to pass a suction catheter into the nasopharynx and oral cavity will give an initial suspicion of the diagnosis, but nasal endoscopy is needed to further investigate. Endotracheal intubation is often required for definitive airway stabilization before any diagnostic or therapeutic intervention can be employed. Bilateral atresias almost exclusively present in the neonate because the condition is virtually incompatible with life; however, rare cases have been reported to be discovered later in life. The diagnosis is often delayed until later in childhood when the child is evaluated for unilateral rhinorrhea not responding to medical management. In older children, unilateral atresia should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating unilateral nasal airway obstruction. Rarely, the condition remains undiagnosed until the child is undergoing an adenoidectomy or alternative procedure for nasal airway obstruction. This narrowing will end blindly with varying degrees of bony and membranous involvement. No randomized clinical trials to date have been performed to demonstrate any advantages of a particular technique. A Cochrane systematic review also was not able to identify any significant advantage or disadvantage to the various techniques utilized. The development of the 120 degree endoscope with a palate retractor has enhanced the safety of this technique by allowing for superior visualization of the surgical site from the nasopharyngeal side of the choanae. An important addition to this technique is to use the back-biting forceps to remove the lateralized posterior vomer to further open up the choanae. This also creates a three dimensional opening which reduces the tendency for circumferential scaring. Depending on the position and thickness of the pterygoid plates, a drill can also be used transnasally to drill the anteriorly thickened and medialized portion of the pterygoid plates of the maxilla. Prior to the advent of endoscope technology, transpalatal repair provided the best exposure. Though principally of historical perspective, this technique remains potentially useful in children with severely deranged craniofacial structure. It involves a transoral exposure with an incision made in the palate to expose the palatine bone and atretic plate which are removed along with the vomer as in other techniques. This technique has the disadvantage of a significant incidence of postoperative orthognathic and orthodontic complications usually requiring future surgical correction. Stenting involves the use of an appropriately sized endotracheal or similar tube that is secured at the choanae and remains in place for several weeks postoperatively. Mitomycin-C has also been described as a topical intraoperative treatment to help reduce scar formation. Postoperative dilations are also common, with often one or two subsequent dilations needed after the initial surgery to maintain patency. Another adjunct for the endoscopic transnasal approach involves using image-guided surgical navigation which can be useful in confirming landmarks and surgical trajectory. While the overwhelming majority of choanal atresia cases can be repaired adequately without image-guidance, some authors have found it useful in certain cases. This system includes the paired punctum of the medial canthi of each eye through the nasolacrimal sac via the valve of Rosenmueller. The nasolacrimal sac drains through the vertical nasolacrimal duct to the inferior meatus via the valve of Hasner. Congenital obstruction can occur at these valve sites due to incomplete cannulation during the third through sixth week of gestation. Such obstruction can be unilateral and, on occasion, bilateral, causing a cystic swelling of the lateral nasal wall(s) which can impinge upon the nasal airway. Diagnosis is made upon endoscopy with visualization of a cystic swelling of the anterior nasal cavity emanating from the inferior meatus. Secondary infection of the obstructed nasolacrimal system can result in dacrocystitis. A computed tomography scan can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis and establishing a treatment plan. If presenting with dacrocystitis, early recognition and antibiotic therapy is imperative to prevent orbital complications. Surgical treatment involves re-establishment of the drainage system through nasolacrimal probing often with the use of Crawford type silastic tube stents for several weeks. Some authors have advocated marsupialization of the cyst without stenting via an intranasal approach with endoscopic forceps or a microdebrider; this approach has been shown to decrease the risk of granulation tissue or scar formation caused by stenting. Nasal turbinate hypertrophy can also present with congenital nasal airway obstruction. These structures are formed in the 6th week of gestation with the maxilloturbinal protruding from the lateral maxillary portion of the nasal wall forming the inferior turbinate, and the ethmoid contribution to the nasal wall forming the middle and superior turbinates from its protrusion known as the ethmoturbinal. Obstruction in the majority of cases results from mucosal swelling; less frequently the size and shape of the bony concha can also result in obstruction. The conservative therapy approach is the use of topical decongestants and steroids to address the mucosal hypertrophy. Should such medical measures fail, submucosal cauterization, radiofrequency reduction or debridement of the hypertrophied turbinates can be effective. Congenital vascular lesions are relatively common and can present in the external nose or nasal airway. It is important to differentiate between these two lesion categories in order to project the natural course of the lesion from a treatment standpoint. Infantile hemangiomas are commonly not present at birth but appear within the first few days to weeks of life. They typically exhibit a rapid proliferation phase within the first year of life and then begin a long course of involution. By contrast, vascular malformations typically present at birth and rarely involute without intervention. They may present as a purely cosmetic disturbance on the external nose, but can also present anywhere along the nasal airway with varying degrees of nasal airway obstruction. Hemangiomas can be treated conservatively with propranolol and steroids systemically which may induce regression. Surgical intervention may be necessary if the airway obstruction is severe or unresponsive to medical management. Nasal endoscopy is needed to rule out an underlying anatomic abnormality or alternative obstructive mass, especially if the child fails to respond to initial treatment for suspected rhinitis. By definition these children will experience these symptoms in the absence of fever development. Idiopathic neonatal rhinitis can be distinguished from infectious rhinitis by the lack of purulent discharge, and from allergic rhinitis because of a lack of other allergic symptoms such as sneezing, watery eyes, or abnormal immunoglobulin profile.

Purchase 100 caps gasex with amex

In the lower lid gastritis dieta en espanol best gasex 100 caps, the fat lies in three compartments: medial, central, and lateral. Temporoparietal fascia Loose areolar tissue Superficial layer Deep layer Deep temporal fascia the levator palpebrae superioris muscle is the primary elevator of the upper eyelid and is innervated by the oculomotor nerve. The levator muscle arises from the orbital apex and courses anteriorly where it thins to a broad aponeurosis that inserts onto the anterior surface of the tarsal plate. The supratarsal crease is created by anterior extension of some of the fibers to attach to the dermis of the eyelid skin. In the Asian lid, aponeurotic fibers do not attach to the skin, which results in a "single eyelid," without a supratarsal crease. Acquired ptosis of the upper eyelid often is a result of levator dehiscence from the tarsal plate and must be identified preoperatively. Fat-repositioning procedures target the arcus marginalis as the site of fat release. The ideal position and shape of the eyebrow is quite subjective and varies according to gender, ethnicity, and current fashion trends. The brow gradually tapers to a handle shape, with the lateral third of the brow coursing above the superior orbital rim in women and at the rim in men. It terminates laterally at a point tangent to an oblique line drawn from the lateral nasal ala to the lateral canthus. The medial aspect of the brow begins at a point tangent to a vertical line drawn through the medial canthus and lateral nasal ala margin and terminates laterally at a point tangent to an oblique line drawn from the lateral nasal ala to the lateral canthus. The apex of the brow arch should lie between the lateral limbus of the cornea and the lateral canthus. Brow ptosis exists when the distance from the mid-pupil to the top of the brow is less than 2. Conjunctiva Lower lid tarsal plate Orbital septum Postseptal fat Orbital rim periosteum Transverse facial a. Excessive displacement of the medial portion of the eyebrows along with deep glabellar furrows may project expressions of anger or malice. A similar lateral hooding or drooping of the eyebrows suggests a fatigued or sad appearance. McKinney and colleagues described the existence of brow ptosis when the distance from the mid-pupil to the top of the brow was less than 2. Farkas and Kolar found that the most attractive women had a relatively smaller upper third of the face compared to the middle and lower thirds of the face. Periorbital Complex the ideal esthetic appearance of the upper eyelid varies with gender and ethnicity. If the sclera is visible between the lid margin and limbus, lid retraction is present and may be due to thyroid ophthalmopathy. Ptosis or drooping of the upper eyelid can be congenital or acquired and should be evaluated preoperatively. In evaluating candidates for rejuvenation of the upper third of the face, it is important to keep in mind the esthetics of the brow and the upper third of the face. The need for an upper lid blepharoplasty may either be obviated by a brow lift or it may markedly reduce the requirements for skin excision. The entire orbital complex, brow position, frontal hairline, hair density, forehead contour, forehead rhytides and furrows caused by the actions of the underlying musculature should all be considered in the preoperative assessment. There are several surgical approaches, endoscopic, coronal, trichophytic (described below), direct, and mid forehead. The latter two choices are less commonly used and more appropriate for patients with facial paralysis or in men with thick and heavy skin with prominent forehead rhytides. The ideal candidate for the endoscopic approach has the following characteristics: female, low hairline, abundant hair, flat contour of the forehead, normal or thin skin, and moderate brow ptosis. Patients requiring extensive bone re-contouring may be better treated with an open procedure. Patients with thick, heavy sebaceous skin and severe brow ptosis are less favorable candidates and may be better served with conventional open skin excision techniques (coronal or trichophytic approaches). Also, surgical weakening of the brow depressor muscles is often technically easier using the open approaches. Finally, patients with high hairlines, sparse hair, male pattern baldness, and rounded foreheads are less ideal candidates for the endoscopic approach. Regardless of the choice of incisions or approaches, there are basically four steps in executing the brow lift: 1) placement of precise incisions; 2) dissection and adequate release of the scalp and forehead; 3) myotomy of the desired facial expressive muscles; and 4) elevation and fixation of the forehead to the desired level. The two paramedian incisions are placed at the level of the lateral limbus or canthus. The two temporal incisions are needed for dissection over the temporalis fossa and allow better positioning the lateral portion of the brow. For the coronal brow lift approach, the skin excision is fusiform and placed 5 to 6 cm behind the anterior aspect of the hairline. A curvilinear incision is drawn to parallel the hairline with the blade beveled parallel to the natural axis of the hair follicles. The amount of skin excised is determined preoperatively, generally about 1 to 2 cm. The temporal incisions should be tangent to a line between the lateral limbus of the cornea and the lateral alar base. The temporal incisions may be placed more laterally, depending on individual esthetic desires and goals. Usually the paresthesia resolves over time, but it can be bothersome to patients during the recovery. Candidates who have a high hairline may be best served with a trichophytic approach. The incision is made in the gradual transition zone between the thick hair of the scalp and the thin wispy hair at the true hairline. The incision parallels the natural curvature of the hairline, and the excision pattern resembles a gentle W-plasty. The lateral extensions proceed into the temporal hair about 4 to 5 cm bilaterally. The goal is allow the hair follicles along the anterior hairline to grow through the incision to help camouflage the scar. Meticulous closure of the anterior hairline is essential for a successful cosmetic outcome. The main disadvantages of this approach are potentially a more visible incision compared to the endoscopic approach and paresthesia behind the incision line. In all brow-lifts, regardless of the surgical approach, the plane of dissection over the skull can be either subperiosteal or subgaleal. The temporal incision is extended down to the superficial layer of the deep temporalis fascia. Using a freer elevator, the dissection is continued along this plane and the temporal dissection is connected to the subperiosteal plane of the forehead by sharply dissecting the transition zone at the temporal crest line. The temporal dissection is continued to the level of the zygomatic arch and the zygomaticofrontal suture line. If the dissection is in the correct plane, the temporal fat pad in the elevated flap should become visible as one nears the zygomatic arch. A branch of the zygomaticotemporal communicating vein ("sentinel vein") is often encountered when dissecting near the zygomaticofrontal suture line. The vein can either by cauterized with a bipolar cautery or gently dissected from the surrounding tissue. Bleeding caused by injury to this vein can lead to poor visualization, and possibly inadvertent injury to the facial nerve from cauterization or further dissection. Overzealous upward retraction in the temporal area should be avoided as it may cause traction neuropraxia of the frontal branch of the facial nerve. It is important to release fully the entire length of the superior arcus marginalis to achieve adequate brow elevation. The periosteum and galea are horizontally scored at this point, exposing the corrugator muscle, procerus muscle, supraorbital nerve, and supratrochlear nerve. In patients in whom glabellar-muscle modification is desired, the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves are dissected from the corrugator muscles by using a gentle vertical spreading motion with Takahashi forceps.

Cheap gasex 100caps overnight delivery

The identification of the thyroid notch is the most dependable anatomic landmark in the pediatric airway diet lambung gastritis gasex 100 caps without a prescription, and its identification becomes especially important when carrying out revision surgery. Once the laryngotracheal structures are skeletonized, a midline thyrotomy is carried out. The extent of this thyrotomy is determined by the site and severity of the stenosis. If placement of a posterior graft is anticipated, the anterior commissure may have to be split. This can be facilitated by using a combined endoscopic technique in which a surgical assistant provides rigid endoscopic illumination to guide the operating surgeon working through the neck. The most common site of an incomplete division is the inferior extent of the posterior cricoid plate. Suture placement for posterior grafting is not necessary when flanges are created and bilateral undermining of the posterior cricoid plate is carried out. The bilateral flanges approximate two to four mm while the central portion (with perichondrium facing into the airway) will usually only need to measure four to five mm in width and three to four mm in height to provide for adequate distraction. Once the tube is placed, the size of the anterior graft (if needed) is determined and sutured into place. If a multi-stage procedure is planned, a stent is placed and secured with non-absorbable suture prior to placing the anterior graft. The stent should not be placed higher than the arytenoid area to prevent aspiration, and the edges of the stent should be smoothed to avoid excessive risk of granulation formation. Airtight-airway closure may decreased the risk of infection, and this closure may be attainable more easily with tissue glue. A drain is placed under the strap muscles and left in place for three to five days to avoid subcutaneous emphysema. Perioperative antibiotics and reflux medication, along with sedation and pain management, are best managed by pediatric intensivists. The goal is a spontaneously breathing child with limited narcotic and muscle relaxant use so as to avoid prolonged withdrawal and muscle weakness. For single-stage reconstructions, endotracheal removal can take place three to seven days postoperatively depending on whether anterior or posterior grafts were placed. Posterior grafting requires a longer intubation period to ensure adequate stabilization in the airway. Twenty-four hours prior to extubation, the patient is given intravenous corticosteroids. On the day of the planned extubation, the airway is evaluated with a rigid endoscopy to ensure proper healing. If the airway is safe, the child is extubated in the operating room suite or in the intensive care unit. For multi-stage procedures, the stent is usually left in place for two to four weeks, depending on the severity of the stenosis, and is removed endoscopically. The child then undergoes a capping and decannulation trial, with interval operative endoscopic evaluations, to monitor appropriate healing. Operation specific decannulation rates and overall decannulation rates vary depending on the initial grade of stenosis, with higher rates being obtained in less severe stenosis. Both endoscopic and open approaches provide for viable alternatives depending on the variables mentioned above. Also, in some reviews, endobronchial tumors and pulmonary parenchymal tumors are included. Although hemangioma meets the definition of a benign tumor, this entity is usually regarded as a vascular anomaly which presents in the first few months of life. It is discussed more extensively in Chapters 75, "Congenital Anomalies of the Larynx and Trachea" and 82, "Vascular Tumors and Malformations of the Head and Neck. Endoscopic management of tracheal stenosis is more challenging from an access standpoint especially in young children with small airways. Lesions amenable to endoscopic treatment include early soft stenosis and thin webs of short length. Keys to successful laser use include avoiding circumferential application and involvement near the carina. Augmentation techniques are similar to those described in the treatment of subglottic stenosis. Augmentation with non-vascularized grafts is comparatively less frequently employed in the trachea because of a propensity for granulation tissue at anastomotic sites and a high incidence of graft breakdown. Determining the optimal approach again depends mainly on the length of the stenotic segment. Besides measuring the length of the stenotic segment, a key determination is whether the procedure can be carried out through the neck or requires a chest incision. Laryngeal and tracheal releasing maneuvers include suprahyoid or infrahyoid release and tracheal mobilization. For stenotic segments involving greater than one-third of the trachea, slide tracheoplasty has become a widely used technique in the pediatric population. The most common pediatric malignant tumors include mucoepidermoid carcinoma and malignant fibrous carcinoma. There is the suggestion that tracheal tumors are more likely to present posteriorly, and that malignancies are more likely to occur in the distal trachea than in the proximal airway, but definitive statements in this respect are not possible due to the relative rarity of these lesions. These children often then present months to years later in respiratory distress once approximately 50 to 90% of the trachea becomes occluded. A high index of suspicion for a tracheal neoplasm is necessary in children whose wheezing does not improve with medical management. The goal of airway evaluation is to define the pathology of the mass via biopsy, determine the extent of airway obstruction, and evaluate for other possible lesions. It is imperative to keep the child breathing spontaneously during this evaluation to avoid loss of the airway if a completely obstructing lesion is present. Complete obstruction may be identifiable on preoperative imaging evaluation, but in many patients, sedation is required for imaging which can lead to unexpected airway loss in the radiology suite. If the airway obstruction is encountered during operative evaluation, mask ventilation can be carried out while a tracheotomy is performed distal to the lesion. A laser delivering bronchoscope or flexible laser can be of help in obtaining hemostasis. Treatment and Follow-Up procedures may require a temporary tracheostomy or laryngeal stenting if grafting materials are used for reconstruction. Adjunctive chemotherapy and radiation therapy are dependent on the final pathology of the tumor. Although trauma accounts for 35 to 50% of childhood mortality, less than 1% of blunt trauma leads to laryngotracheal injury. The pediatric larynx lies at the level of C3 to C4 vertebra affording greater protection by the hyoid and mandible. The broader and more pliable cartilage also allows for increased endolaryngeal protection. There is, however, an increased risk of swelling due to the loose attachment of the submucosal laryngeal tissues to the perichondrium. This arrangement predisposes children to airway compromise due to minimal edema in small-diameter airways. Both open and endoscopic approaches are advocated depending the evaluation of a child with a suspected larynon the site and pathology of the lesion. Endoscopic geal or tracheal tumor may include several diagapproaches should be limited to tumors that do nostic studies in addition to tracheobronchoscopy. For isolated laryngeal lesions, an open approach via a thyrotomy and extended cricoid incision provides optimal access for removal. Depending on the site of the tracheal lesion, trans-cervical or trans-thoracic approaches may be necessary. Key points to determine are the location of the mass in relation to the carina and the subglottis, whether resection will allow for primary anastomosis, and whether enough trachea can be mobilized to ensure a tension-free repair. Postoperative-airway management will depend on the size of the child and the ancillary support of the hospital. Near obstructing glomus tumor of the trachea treated with en bloc removal via a tracheal undergoing tracheal resection can be extubated at identified after multiple attempts at intubation by emergency the end of the procedure.

Gasex 100 caps on-line

The final principle treating gastritis naturally order 100 caps gasex with mastercard, stress relaxation, is the decrease in stress on skin when it is held in tension at a constant strain for a given period of time. Stress relaxation occurs days to weeks after flap placement and is due to the increase in skin cellularity and permanent stretching of skin components with wound healing and contracture. The concept of serial excision is based upon the principles that skin closed under tension will display stress relaxation and creep over time. The probability of tip necrosis has been directly related to both the length of the flap and distance from proximal vessels and the tension under which it is closed. In essence, longer flaps display a higher probability of tip necrosis when placed under the same closing tension as shorter flaps. Undermining is the usual surgical technique for relieving tension in a flap but may not always represent the best means of correcting for excessive tension. Undermining has been shown to be of little benefit on tension beyond four centimeters. Other studies performed on animals demonstrated that excessive undermining actually increases flap necrosis probably by decreasing the vascular supply from both the superficial and deep vascular plexus. The first is the blood supply to the flap through its base, and the second is the formation of neovascularization between the flap and the recipient bed. It has been thought that the survivability of a flap depends entirely on the width of the base. However, the surviving length of random pattern flaps is determined by perfusion pressure within the arterioles and intravascular resistance. Widening the base of a flap does not affect either perfusion pressure nor intravascular resistance. Widening the base of a flap is necessary to a certain critical ratio, but more is not necessarily better when it comes to flaps; and there is no benefit to widening the base beyond that ratio. The literature suggests that a length to width ratio of 3:1 to 4:1 will result in a viable random pattern flap for the face or scalp. In random flaps, this was performed by incising the long axis of the flap and undermining without dividing the ends of the flap. Axial flaps are incised around the margins excluding the base, or vascular pedicle, of the flap without undermining. In this way, the flaps are initially incised and then left in place at the donor site to be transposed and inset into the recipient bed after one to two weeks. Of note, any benefits gained from a delayed flap are lost if delayed beyond three weeks. It is thought that delaying the flap improves blood flow after insetting by reorienting vascular channels and inducing the formation of new vascular collaterals. Management of Complications the same complications to wound healing apply to skin and tissue flaps as well. The most common causes of complications are poor flap design and increased tension from closure. These concerns must be addressed prior to forming the flap and while in the operating room. Potential postoperative complications of local skin flaps also include infection, hematoma, ischemia, flap necrosis (distal flap or tip necrosis), dehiscence, and an undesirable cosmetic result. Some flaps, such as a transposition flap, tend to have decreased tension on the distal extension of the flap. Adequate perfusion is assured if, at the conclusion of the inset, the flap is pink with brisk capillary refill. The progression of ischemia to necrosis may be in a stepwise fashion with blanching and increasingly prolonged capillary refill until capillary refill is no longer evident with direct pressure. The natural consequence of poor perfusion without intervention follows a stepwise fashion as well. Tissue ischemia causes cell death, which is initially superficial, but may progress to full thickness. Eschar formation leads to widening of the scar secondary to poor migration of epithelial cells and goes on to separation of the eschar with an exposed defect and healing by secondary intent. Clinical symptoms include an edema, purplish or bluish hue to the flap with dark colored blood on pinprick. Initial management should include removal of tense sutures that are potentially compromising venous drainage. It may be necessary to explore the vascular pedicle to remove any kinking or compression caused by hematoma formation. In addition, multiple punctures may be made with a 22-gauge needle to relieve venous hypertension. Should medicinal leeches be utilized, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended to prevent Aeromonas infection. Although medicinal leeches are raised in a sterile environment, their digestive tracts are colonized with this microorganism and it is transferred in the saliva. Mechanical pressure from a wound dressing applied too tightly, hematoma, or a kinked pedicle is a common cause that can be remedied initially. It is recommended that adequate perfusion be assured prior to leaving the operating room. Otherwise, the option of further delay of flap placement is lost; nevertheless, the outcome may be a necrotic flap in its original position with a remaining tissue deficiency. It is important to note that although a flap can survive arterial insufficiency for up to 13 hours, venous congestion will cause flap failure within three hours. Therapy is initiated through multiple "dives" in which 100% oxygen is administered at two to three times atmospheric pressure. This results in an increased amount of dissolved oxygen in plasma, which increases the oxygen level in the peripheral tissue by a reported 10- to 20-fold. First of all, it encourages capillary neovascularization within the flap thus increasing blood supply and oxygen delivery to the ischemic tissue. Complications may be various and usually result from either barotraumas or oxygen toxicity. These complications can include pneumothorax, barotrauma to the middle ear with tympanic membrane perforation, seizure, pulmonary toxicity, myopia, and an increased rate of cataract formation, particularly in patients with preexisting cataracts. Myopia usually resolves within six months following treatment, but the other complications can be serious and long term. However, a wound may benefit from some debridement as it increases migration of epithelial cells. This is counterintuitive; as previously discussed, scabbing causes widening of the scar. Although debridement is rarely necessary, failure of a flap may necessitate another reconstruction if more conservative measures fail to provide adequate coverage of the tissue defect. Infection, another dreaded complication in surgery, is surprisingly uncommon in head and neck local flaps, although higher than in traditional facial surgery. Plausible reasons include delayed flaps becoming contaminated, higher colonization rates in the head and neck regions, for example, nose and oral cavity, and lastly, because those undergoing surgery for head and neck flaps usually have increased risk factors for infection including malignancy, diabetes, and malnutrition. Infection may be as problematic as dehiscence with widening or thickening of scar or as devastating as flap necrosis or sepsis. For these reasons, prevention of infection is critical because of the potential for catastrophic consequences. Simple measures, such as observance of sterile technique, handling tissues gently, avoidance of aggressive hemostasis, closing and suturing with as little tension as possible, and postoperative irrigation with hydrogen peroxide to remove dried blood which increases local bacterial load, are recommended to prevent untoward events. Antibiotic prophylaxis has been proven effective for clean-contaminated operations such as with delayed wound closure, but not necessarily for clean wounds. As expected, Staphylococcus aureus as a skin contaminant is the most common pathogen isolated from infected wounds. Management usually includes opening up a small area of the incision to facilitate drainage of pus and decrease bacterial load as well as pressure on the flap. Any purulent fluid should be sent for culture for identification of the microorganism and determination of its antibiotic sensitivities, and the patient should be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics until a more specific antibiotic is indicated by the sensitivities. When the drainage stops and the infection has resolved, the wound is allowed to close.

Gasex 100 caps with mastercard

Transcutaneous blepharoplasty frequently alters lower eyelid margin contour and may cause frank lower eyelid retraction while only modestly reducing lower skin wrinkles or folds gastritis medication list buy gasex pills in toronto. When redundant skin must be excised, the trans-conjunctival approach may be combined with anterior skin excision to preserve the orbital septum and decrease the risk of postoperative lower eyelid retraction. Skin quality issues such as rhytides (wrinkles) should be addressed using concomitant resurfacing techniques. Removal of redundant skin, As with upper blepharoplasty where the upper eyelid and brow form one continuous unit, the lower eyelid functions as a continuum with the mid-face. Understanding the dynamic forces that dictate lower eyelid position and contour requires conceptualization of lower eyelid, cheek, and nasolabial anatomy. One critical difference in anatomy between the upper and lower eyelids is that the orbital fat in the lower eyelid is accessible via a trans-conjunctival approach. This approach avoids violation of the orbital septum by incising the lower eyelid retractors which travel posterior to the septum and are separated from the septum by the orbital fat. This technique decreases the likelihood of postoperative cicatrix or scarring of the orbital septum. The lower eyelid anterior lamella continues onto the mid-face and is composed of skin and orbicularis oculi muscle while the posterior lamella is composed of tarsus and conjunctiva. The orbital septum originates from the arcus marginalis along the inferior orbital rim and fuses with the inferior border of the tarsus. Because it partitions the anterior and posterior lamellae, the orbital septum may be considered the middle lamella. The orbital septum also partitions the lower eyelid orbital fat pads and the preseptal tissues as the lower eyelid fat compartments lie just posterior to the septum. The lower eyelid retractors border the orbital fat posteriorly and superiorly and then fuse with the orbital septum approximately five mm inferior to the inferior tarsal border before inserting upon the tarsal plate. The lower eyelid retractors adhere closely to the lower eyelid palpebral conjunctiva. The arcuate expansion represents a fascial extension of the inferior oblique muscle sheath and Lockwood ligament and inserts on the anterior portion of the inferolateral orbital rim. The inferior oblique muscle originates at the anterior medial orbital rim and separates the medial and central fat compartments as it passes posteriorly and laterally under the equator of the globe. The arcuate expansion and the inferior oblique muscle serve as important surgical landmarks during lower blepharoplasty. The orbicularis muscle migrates inferolaterally, contributing to malar bags and festoons. Superior to the orbital rim, the attenuated septum and preseptal tissues allow bulging of the orbital fat. Because sensory nerves of the conjunctiva and orbital fat originate in the orbit, the surgeon directs the needle toward the inferior orbital rim, walks the needle posteriorly until it touches the orbital floor, and injects approximately 1 mL of anesthetic in each fat compartment. Approximately 2 mL of the same solution is injected trans-cutaneoulsy within the orbicularis muscle in patients requiring skin excision. The surgeon should allow approximately 10 minutes for maximum vasoconstriction by the epinephrine. The assistant retracts the medial third of the lower eyelid with a small Desmarres retractor to expose the cul-de-sac. A nonconductive eyelid plate is placed over the globe into the inferior fornix to ballotte the globe posteriorly. The surgeon palpates the medial aspect of the inferior orbital rim with a needle-tip monopolar cautery. The incision should be made at least fourmm inferior to the inferior punctum to avoid damage to the canaliculus. Traditional lower blepharoplasty may reduce areas of fat bulging superior to the orbital rim, but it does not address the area of tissue paucity over and inferior to the rim, nor the malar bags. The area of tissue paucity may be managed with concomitant fat repositioning or mid-face elevation techniques. The tear trough abnormality may be treated with implant material to fill the bony defect. Volume augmentation with fat grafts/ injections or fillers can be considered as well. The incision begins at the caruncle and extends laterally toward the lateral canthus. Repositioning of the Desmarres retractor so that its blade is in the wound itself will now provide wider exposure. The closer each fat compartment is opened to the orbital rim, the easier and the less chance of encountering bleeding or damage to the inferior oblique muscle. Each of the three fat compartments can be separated with blunt dissection using a cotton-tipped applicator and gentle retraction with a 0. The lateral fat contains more septae than the central fat pad, and the fat may not herniate as easily. After excision of the superficial portion of the lateral fat pad, the posterior fat comes forward more freely. This structure should be identified to ensure identification of the medial fat compartment and to avoid injury to the inferior oblique muscle. The medial fat may migrate around the medial edge of the lower eyelid retractors from the muscle cone. Unlike the upper eyelid, where the palpebral vessels lie on the surface of the medial fat pad, the lower palpebral vessels travel directly through the medial fat compartment. The blood vessels associated with each fat compartment should be cauterized under direct visualization, especially medially. After each fat pocket is exposed, excision is carried out in a graded fashion with the monopolar cautery instrument, incisional laser, or cold steel. Intraoperatively, the lower eyelid is redraped and the contour examined to ensure adequate contour. Slight pressure on the globe simulating upright posture should restore a single, smooth contour from the eyelid margin to the orbital rim. After fat removal, the lower eyelid margin is pulled superiorly to realign the conjunctival wound edges. It is not necessary to close the conjunctiva and lower eyelid retractors at all, however, two or three interrupted 6-0 plain gut sutures may be used if the tissues do not appear well opposed. Trans-conjunctival lower blepharoplasty may be combined with a skin pinch to address cutaneous redundancy. When performed correctly in patients without preexisting horizontal eyelid laxity, this technique does not produce changes in lower eyelid position. Fat repositioning can be performed in conjunction with or in lieu of fat removal to impart a rejuvenated lower eyelid appearance. The pedicle can be lengthened by narrowing its base, but this decreases blood supply. The periosteum is then elevated with a Freer periosteal elevator in the area beneath the nasojugal fold. These more anterior host pockets may allow for better flap vascularization but may transmit more contour irregularities of the fat pedicle to the overlying skin. The Desmarrres retractor is withdrawn occasionally to observe the impression of the periosteal elevator beneath the skin to ensure proper inferior extent of the sub-periosteal or pre-periosteal dissection beneath the nasojugal fold. The fat pedicle is isolated at its distal end on a double-armed absorbable suture. The arms of this suture then advance the pedicle into the dissection pocket as they are passed from the inferior extent of the dissection pocket through full thickness tissues just inferior to the nasojugal fold and tying them over the skin. While many patients require repositioning of only the medial fat pad, all three lower eyelid fat compartments can be mobilized to add volume beneath a prominent inferior orbital rim or in the more lateral periorbital hollows. Postoperative care includes the use of ophthalmic antibiotic ointment applied to the wounds and in the eyes three to four times daily. Patients are given acetaminophen 650 mg with or without oxycodone or hydrocodone 5 mg for pain relief. The patient stabilizes in the recovery room for approximately one hour and is observed for signs of hemorrhage.

Purchase gasex with amex

As an alternative technique gastritis diet 2 go cheap gasex 100caps overnight delivery, serial (incomplete) "picket fence" incisions along the deviated L-strut segments may be used to straighten a scoliotic L-strut. While this method can realign a warped or deviated L-strut, the use of multiple incisions may also destabilize the L-strut and lead to persistent deformity. In instances of aggressive L-strut manipulation, unilateral splinting grafts of septal cartilage or bone are placed and secured with sutures to serve as support to the treated segment. Although the hemitransfixion approach to the nasal septum can be safely used in conjunction with external rhinoplasty, the nasal septum can also be accessed through the external rhinoplasty approach without the need for a hemitransfixion incision. Instead, the caudal aspect of the septum is exposed in a submucosal dissection plane by separating the membranous septum via the transcolumellar incision. Because this approach demands considerable dissection within the columella and membranous septum, it is not suitable for all patients. Nevertheless, the external rhinoplasty approach is an excellent alternative for patients with complex deformities of the L-strut since exposure of the nasal base is optimized. The low complication rate of primary rhinoplasty is most likely explained by a generally youthful and healthy patient population, the naturally robust blood supply of the facial soft tissues, and the physiologic resilience of human nasal cartilage. And while virtually all patients experience some degree of acute soft tissue swelling and/or ecchymosis as a byproduct of nasal surgery, acute surgical inflammation is almost always transient and short-lived. Perhaps the most common acute complication of cosmetic nasal surgery is excessivesurgical bleeding and/or postoperative epistaxis. In contrast to perioperative bleeding which is typically mild and without lasting sequelae, postrhinoplasty wound infections may potentially result in significant tissue destruction and compromised surgical outcomes. Fortunately, infections of the surgical site are relatively uncommon in primary rhinoplasty. In fact, some authors have recommended eliminating the longstanding practice of routine antibiotic prophylaxis in all but the high-risk patient. Although the typical rhinoplasty patient presents with normal immune competence, surgical breaches in the protective epithelial barriers and vascular congestion resulting from surgical tissue disruption combine to impair baseline immune function and predispose to acute bacterial infection. And in patients with pre-existing vascular impairment, such as those with previously-operated noses, autoimmune vasculitis, a history of cocaine-induced ischemic necrosis, or other forms of microvascular compromise, surgical wound infections are considerably more common and often more severe. And while antibiotic-resistant infections are typically more severe, virtually any prolonged bacterial infection can damage a newly-operated nose as a consequence of cartilage resorption, soft tissue fibrosis, and/ or scar contracture. Although early recognition and treatment with appropriate antimicrobial therapy is essential, isolating and characterizing the bacterial pathogen is often hindered by the absence of frank suppuration. Treatment strategies are mostly empirically based since culture and sensitivity data from sterile isolates are often unavailable. And since the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of drug-resistant pathogens often vary widely within a given community, achieving effective antimicrobial therapy with an empiric "hit or miss" approach may prove challenging. Hence, for suspected drug-resistant microorganisms, multi-drug therapy is often necessary to obtain effective broad spectrum coverage and to hasten the therapeutic response. Since even a bacterial cellulitis can potentially lead to resorption of cartilage grafts with subsequent soft tissue contracture and fibrosis, preventative measures and close surveillance are recommended in all rhinoplasty patients. Copious intraoperativesaline irrigation of the surgical field, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in high-risk patients, frequent use of post-operative saline nasal rinses, and frequent hand washing by the patient and care providers will all help to mitigate infection risk. Supportive measures that prevent or diminish soft tissue swelling and improve soft tissue perfusion will also help to potentiate immune function both during and after nasal surgery. Root Cause of the Failed Rhinoplasty Unlike wound infections which are infrequent, technical failures are probably the most common cause of the unsatisfactory rhinoplasty outcome. Although adverse rhinoplasty outcomes may result from a wide range of root causes, one of the more frequent technical causes is a spurious preoperative cosmetic analysis. Sadly, failure to derive an accurate cosmetic analysis often leads to initial treatment errors that are compounded, sometimes repeatedly, by subsequent steps in the surgical procedure. In such instances, the final result is usually a cosmetically and functionally devastated nose. Fortunately, digital photography and computer imaging tools are now available that make cosmetic analysis more reliable and far less prone to misinterpretation. And since the planned cosmetic intervention can be "previewed" with computer simulation, validity of the cosmetic analysis can be visually confirmed to the mutual satisfaction of patient and surgeon alike. Without question, an individualized treatment plan derived from a valid cosmetic analysis is the first step in achieving a satisfactory rhinoplasty outcome, and a one-sizefits-all "cookbook" approach to rhinoplasty that disregards individual cosmetic nuances should be avoided. Although an erroneous cosmetic analysis is a frequent cause of the failed rhinoplasty, other common causes include poor technical execution, poor surgical judgment, adverse wound healing responses, and patient non-compliance. Occasionally, adverse wound healing responses or patient non compliance will subvert an otherwise well-executed surgical procedure, but far too often technical errors or surgical misjudgment are the root cause of the unsatisfactory surgical outcome. And by far the most common treatment error is over-resection of the skeletal framework. Over-resection of the skeletal tissues results in a constellation of cosmetic and functional abnormalities all stemming from inadequate structural support. In fact, a disproportionate number of noses undergoing revision rhinoplasty are found to have a partiallyamputated skeletal framework with manifestations of insufficient skeletal support including collapse and distortion of the residual nasal cartilage. Although over-resection will usually cause immediate cosmetic and functional sequelae, slowly progressive wound healing responses often exacerbate post-surgical deformities with time, and in the highly susceptible patient, the sequelae of over-resection may slowly worsen for a lifetime. Typically, skeletal over-resection creates an unnatural appearance with a stereotypical "surgical" look that is highly suggestive of poorly executed nasal surgery. Individuals with naturally weak nasal cartilage are particularly susceptible to the adverse effects of skeletal over-resection since their baseline level of structural support is already marginal. Likewise, individuals with contracture-prone skin are also more susceptible to over-resection since the surgically weakened cartilage framework is subject to potent destabilizing forces arising from progressive shrinkage of the overlying skin envelope. And when a surgically over-resected nose is then subjected to additional cartilage softening from age, disease, or repeated wear-and-tear, severe deformities often ensue. Because skeletal over-resection is among the most common and the most destructive of all technical and judgment errors and a largely preventable complication, the remainder of this chapter is devoted to understanding and avoiding the adverse consequences of skeletal over-resection. Alar cartilage shape, projection, rotation, and spacing; coupled with the overlying skin covering, collectively determine the three-dimensional tip contour. Consequently, any cosmetic alteration in surface contour must somehow be derived from surgical changes in one or more of the aforementioned physical parameters. However, cartilage rigidity is the major determinant of structural stability, and structural stability is the primary determinant of nasal shape constancy. Hence, any surgical alteration that purposefully (or inadvertently) reduces cartilage rigidity may ultimately destabilize the nasal tip framework and produce unsightly and potentially progressive changes in surface tip contour. Traditionally, cosmetic modifications of the nasal tip have been accomplished using "excisional" rhinoplasty techniques, in which contour alterations are achieved primarily through (partial) excision of the alar cartilages. As a consequence, over-resection of the lateral crus is a common complication of this widely-used and sometimes unforgiving surgical procedure. Owing to its conspicuous size and shape, many surgeons are far more aggressive when excising cartilage from the ultra-wide nose. Yet the wide nasal tip is frequently composed of unusually weak alar cartilage that is considerably more susceptible to reductions in skeletal volume; and for many large noses, an aggressive cephalic trim can easily lead to unwanted collapse and distortion of the alar remnants. Likewise, noses with contracture-prone nasal skin, and noses prone to age-related losses in cartilage strength are also more susceptible to aggressive cartilage excision since the former results in escalating forces of deformation, whereas the latter leads to a progressive erosion of structural support. And in the susceptible nose, such as the nose with unusually weak tip cartilage, even a conservative cephalic trim may lead to structural destabilization with unwanted functional and cosmetic sequelae. Although the trend in contemporary rhinoplasty is to arbitrarily preserve a "6 mm-wide" crural remnant to prevent crural over-resection, a disproportionate number of unsuccessful rhinoplasty outcomes exhibit stigmatic nasal deformities directly attributable to cephalic over-resection and crural collapse, many with crural remnants well over 6 mm in width. Hence, the cephalic-trim maneuver is at best an imprecise and unpredictable technique that relies upon haphazard reductions in skeletal support to achieve long-term alterations in nasal contour. And because the cephalic-trim maneuver often fails to account for naturally weak cartilage, hostile wound-healing forces, and/or future losses in cartilage stiffness, it is perhaps the most frequently observed technical cause of the unsatisfactory rhinoplasty outcome. The cosmetic and functional complications of the cephalic trim virtually all derive from excessive destabilization of the lateral crura. Cephalic overresection of the lateral crus weakens its longitudinal and/or transverse rigidity thereby exceeding the minimum threshold for adequate skeletal support. The result is a familiar group of stigmatic crural deformities all stemming from surgically-induced structural failure of the lateral crura. When structural failure is restricted to a critical loss of longitudinal crural rigidity, the crural remnant buckles inward resulting in a concave crural collapse. In fact, some authors regard over-resection of the lateral-most cephalic margin as the most destructive. In patients with thin skin and contracture-prone soft tissues, the so-called "shrink wrap" phenomenon may produce dramatic shrinkage of the skin soft tissue envelope sometimes resulting in outward buckling of the alar cartilages, especially when focal weaknesses occur in close proximity to the nasal domes. These highly conspicuous knuckles or bossae are especially common in the over-projected nose when the long, slender alar cartilages are subjected to cephalic over-resection in a misguided attempt to reduce tip projection.