Safe 100mg mebendazole

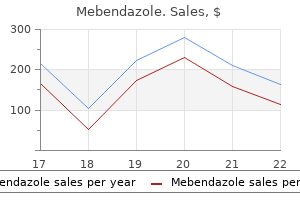

Tightly packed cells change the composition and microarchitecture of cerebral tissue leading to a decrease in extracellular water and resultant restriction in diffusion life cycle of hiv infection mebendazole 100 mg without a prescription. In the acute phase, patients may present with sudden-onset aphasia, dysarthria, hemiplegia, or hemisensory deficits. In such cases, a combination of clinical features and short-term follow-up imaging allows accurate diagnosis. This in turn can facilitate more rapid treatment decisions with greater certainty in the setting of acute stroke. Acute ischemic stroke: overview of major experimental rodent models, pathophysiology, and therapy of focal cerebral ischemia. Matrix metalloproteinase expression after human cardioembolic stroke: temporal profile and relation to neurological impairment. Predictors of hemorrhagic transformation after intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: prognostic value of the initial apparent diffusion coefficient and diffusion weighted lesion volume. The pathophysiology of watershed infarction in internal carotid artery disease: review of cerebral perfusion studies. Diffusion weighted imaging identifies a subset of lacunar infarction associated with embolic source. Higher risk of further vascular events among transient ischemic attack patients with diffusion weighted imaging acute ischemic lesions. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. Prediction of cerebral hyperperfusion after carotid endarterectomy using middle cerebral artery signal intensity in preoperative single-slab 3-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography. The spectrum of presentations of venous infarction caused by deep cerebral vein thrombosis. Transient global amnesia: diffusion weighted imaging lesions and cerebrovascular disease. Key Points Diffusion weighted imaging is an important tool for evaluating brain tumors and can be used for diagnosis, follow-up, and determining the prognosis. Primary central nervous system lymphoma usually demonstrates restricted diffusion due to its histology: the high degree of cellularity and the high nuclear to cytoplasm ratio. Diffusion imaging sequences can be used to assess posttreatment changes and may serve as an early biomarker tool for predicting treatment outcomes, monitoring treatment response, and detecting recurrent cancer. The restricted diffusivity in abscesses is due to the high viscosity of the fluid inside the cavity, which leads to reduced water diffusion,2 whereas the enhancing ring is a fibrous capsule formed by organized collagen fibres. Likewise, the enhancing portion of a tumor is due to viable tumor cells,1 which may demonstrate restricted diffusion secondary to high cell density. The color change cannot be attributed to a bulk effect as with disrupted tracts most frequently seen in infiltrating gliomas. The last pattern described consists in an isotropic or almost isotropic diffusivity within the lesion. In this pattern, the tracts cannot be identified on directional color maps and is observed when some portion of the tract is completely destroyed by the tumor and is commonly observed in high-grade gliomas. A combination of patterns may occur, such as displacement, infiltration, and edema, and these may limit the clinical application of these patterns for tumor grading and differential diagnoses. Heterogeneous appearances and enhancement, surrounding edema, and irregular cerebral surfaces are more commonly detected in atypical meningiomas, but they are not unique to these tumors. Atypical meningiomas have high cellularity and therefore may have restricted diffusion, although this is not a hallmark for these tumors. Identifying tumor borders and peritumoral brain tissue is crucial to surgery success, but difficult to establish in high-grade gliomas. After deciding to reoperate the tumor, the surgeon was in doubt regarding the relationship between the lesion and the corticospinal tract and the superior longitudinal fasciculus. The tractography fused with (d) T1-weighted image demonstrates minimal deviation of the left corticospinal tract, as well as a surgical plane between the tract and the tumor. The lesion demonstrates hyperintensity on (c) diffusion weighted imaging and low signal intensity on (d) apparent diffusion coefficient map, characterizing restricted diffusion. Nevertheless, differential diagnoses with enhancing high-grade gliomas may be difficult. The lesion was high signal intensity on (c) diffusion weighted imaging and heterogeneous signal intensity, predominantly isointense to brain parenchyma, on (d) apparent diffusion coefficient map. The age of patients, imaging characteristics, and tumor location are essential for the diagnosis. Supratentorial tumors are more common in neonates and infants, whereas infratentorial tumors are more common in children older than 2 years. Low- and high-grade astrocytomas in the pediatric population behave similarly to those in adults. This abnormality may paradoxically benefit patients with high-grade gliomas and serve as a prognostic factor. In enhancing nonrecurrent lesions, fibrosis, gliosis, macrophage invasion, vascular changes, and demyelination predominate, and restricted diffusion is seen. Normalization of vasculature causes a reduction in the diameter and permeability of the vessels and often causes a rapid decrease in contrast enhancement (within 24 hours) without a true antitumoral effect. Pseudoresponse is demonstrated when the nonenhancing portion of the tumor increases in addition to the enhancing portion. After the appropriate registration, a voxel-by-voxel subtraction is performed to compare different time points, including postsurgical and pretreatment points. Primary tumor grading and invasion, differential diagnosis between other intracranial lesions, and treatment prognosis may be assessed by such techniques. Differentiation of brain abscesses from necrotic glioblastomas and cystic metastatic brain tumors with diffusion tensor imaging. The correlation between apparent diffusion coefficient and tumor cellularity in patients: a meta-analysis. Differentiation of pure vasogenic edema and tumor-infiltrated edema in patients with peritumoral edema by analyzing the relationship of axial and radial diffusivities on 3. The differences of water diffusion between brain tissue infiltrated by tumor and peritumoral vasogenic edema. Diagnostic value of apparent diffusion coefficient for the accurate assessment and differentiation of intracranial meningiomas. Correlation of apparent diffusion coefficient with Ki-67 proliferation index in grading meningioma. Differentiation of recurrent brain tumor versus radiation injury using diffusion tensor imaging in patients with new contrast-enhancing lesions. Imaging response criteria for recurrent gliomas treated with bevacizumab: role of diffusion weighted imaging as an imaging biomarker. Advantages of high b-value diffusion weighted imaging to diagnose pseudoresponses in patients with recurrent glioma after bevacizumab treatment. Differentiation of true progression from pseudoprogression in glioblastoma treated with radiation therapy and concomitant temozolomide: comparison study of standard and high-b-value diffusion weighted imaging. Statistical analysis of multi-b factor diffusion weighted images can help distinguish between vasogenic and tumor-infiltrated edema.

100mg mebendazole mastercard

In our experience oral antiviral order mebendazole pills in toronto, many tumors with indubitable features of hemangiopericytoma prove to be metastases from other sites, most frequently the meningeal hemangiopericytoma or gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Computed tomogram shows destructive lesion involving body of thoracic vertebra and adjacent rib. A, Intermediate power photomicrograph of spindle-cell tumor with branching staghorn pattern of vascular spaces. B, Low power magnification shows spindle-cell tumor with branching staghorn pattern of vascular spaces. Patients with meningeal hemangiopericytoma metastatic to the extracranial skeletal sites typically have a history of primary meningeal tumor. More recent reappraisal of small series of cases previously diagnosed as hemangiopericytoma of bone with a panel of immunohistochemical and molecular markers indicates that some of these cases can be reclassified as synovial sarcomas or solitary fibrous tumors. The behavior of hemangiopericytoma is difficult to predict, but the prognosis seems to be more favorable than that of high-grade angiosarcoma. A patient who presents with the lesion in a bone invariably has extraskeletal disease. In the classic chronic form, the skeletal involvement usually occurs in the region affected by the skin and soft tissue disease- in the small bones of the feet, often by direct extension. In other forms, the site of skeletal involvement is unpredictable and may appear in any bone. More advanced lesions show complete cortical disruption and extension into soft tissue. The nature of the lesion can be suspected on radiographs if it occurs in the appropriate clinical setting; otherwise, the radiographic features are not specific. The early changes referred to as the patch and the plaque phases have not been described in bone. All lesions reported in bone are diagnosed when the lesion is a well-established nodule with bone destruction sufficient to cause symptoms. The lesion is composed of intersecting arcs of bland spindle cells similar to the pattern seen in well-differentiated fibrosarcoma. Better-developed vascular channels with open spaces are present at the periphery of the lesion. Features of hemorrhage with hemosiderin deposits and scattered inflammatory cells are present. It is most frequent in the Eastern European/Mediterranean region (Italy) and Central Africa. The lymphadenopathic form predominantly involves young African children, who have cervical, inguinal, or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The disease usually develops in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes or in some instances at the site of previous surgery. The fatal outcome is usually due to widespread involvement of the gastrointestinal tract. Differential Diagnosis the separation from other forms of vascular sarcoma is based on the distinctive microscopic appearance and invariable association with extraskeletal disease. Direct extension from overlying skin and involvement of soft tissue in the classic form facilitate the diagnosis of this type of bone lesion. The mortality rate for the classic form ranges from 10% to 20% after a prolonged (approximately 10-year) indolent clinical course. Treatment of these lesions may involve curettage, en bloc excision, and internal fixation of pathologic fractures. The cutaneous lesions appear as protuberant, nonerythematous, firm, dry lesions with a collar of hyperkeratotic skin. The bone involvement can be associated with the skin lesions, but it can also be the presenting sign of the disease. This infectious, nonneoplastic process can mimic a low-grade vascular endothelial bone tumor both radiographically and histologically. On radiographs, bacillary angiomatosis of bone presents as a lytic defect that may disrupt the cortex and extend into the soft tissue. The radiographic findings and clinical symptoms are suggestive of acute osteomyelitis. Multiple concentric layers of proliferating endothelial cells that form cuffs around luminal spaces can be present focally. The intervening hypercellular stromal tissue shows an inflammatory cell infiltrate. In general, the microscopic features mimic those of low-grade vascular endothelial neoplasms. Ill-defined destructive lesion is present with eccentric expansion and periosteal new bone formation. B, Computed tomogram of abdomen in patient shown in A reveals destructive lesion in lower right rib. B, Higher magnification shows details of endothelial-lined vascular slits and bland nuclei in surrounding spindle cells. D, Higher magnification of C shows nuclei of spindle cells with some atypia and slitlike vascular spaces with red blood cells. A, Low power photomicrograph shows arrays of bland spindle cells and an occasional better-developed vascular structure. A, Lytic lesion of maxillary bone is composed of proliferating vessels with plump endothelial cell. Inset (bottom), Vessels with proliferating endothelial cells forming concentric layers and obliterating vascular lumen. Floris G, Deraedt K, Samson I, et al: Epithelioid hemangioma of bone: a potentially metastasizing tumor Hashimoto H, Daimaru Y, Enjoji M: Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia: a clinicopathologic study of 91 cases. Izukawa D, Lach B, Benoit B: Intravascular papillary endothelial hyperplasia in an intracranial cavernous hemangioma. Kimura T, Yoshimura S, Ishikawa E: Unusual granulation combined with hyperplastic change of lymphatic tissue. Ose D, Vollmer R, Shelburne J, et al: Histiocytoid hemangioma of the skin and scapula: a case report with electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry. Rosai J, Gold J, Landy R: the histiocytoid hemangiomas: a unifying concept embracing several previously described entities of 986 13 Vascular Lesions skin, soft tissue, large vessels, bone, and heart. Takahashi A, Ogawa C, Kanazawa T, et al: Remission induced by interferon alfa in a patient with massive osteolysis and extension of lymph-hemangiomatosis: a severe case of Gorham-Stout syndrome. Yamamoto T, Iwasaki Y, Kurosaka M, et al: Angiosarcoma arising from skeletal hemangiomatosis in an atomic bomb survivor. Gonzalez-Llanos F, Lopez-Barea F, Isla A, et al: Periosteal glomus tumor of the femur: a case report. Najman E, Fabecic-Sabadi V, Temmer B: Lymphangioma in the inguinal region with cystic lymphangiomatosis of bone. Azumi N, Churg A: Intravascular and sclerosing bronchioloalveolar tumor: a pulmonary sarcoma of probable vascular origin. Campanacci M, Boriani S, Giunti A: Hemangioendothelioma of bone: a study of 29 cases. Hisaoka M, Okamoto S, Aoki T, et al: Spinal epithelioid hemangioendothelioma with epithelioid angiosarcomatous areas. Maruyama N, Kumagai Y, Ishida Y, et al: Epithelioid haemangioendothelioma of the bone tissue. Battocchio S, Facchetti F, Brisigotti M: Spindle cell haemangioendothelioma: further evidence against its proposed neoplastic nature. Ding J, Hashimoto H, Imayama S, et al: Spindle cell haemangioendothelioma: probably a benign vascular lesion not a low-grade angiosarcoma-clinicopathological, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Imayama S, Murakamai Y, Hashimoto H, et al: Spindle cell hemangioendothelioma exhibits the ultrastructural features of reactive vascular proliferation rather than of angiosarcoma. Terashi H, Itami S, Kurata S, et al: Spindle cell hemangioendothelioma: report of three cases. Winter A, Siu A, Jamshidi A, et al: Spindle cell hemangioendothelioma of the sacrum: case report. Dunlop J: Malignant hemangioendothelioma of bone: case report of en bloc resection and prosthetic hip replacement.

Purchase mebendazole 100mg on line

Nonossifying fibromas produce eccentrically oriented lucencies antiviral zoster mebendazole 100 mg for sale, whereas a focus of fibrous dysplasia is indicative of a central intramedullary lesion. Knowledge of the latter helps prevent the less frequent error of diagnosing a nonossifying fibroma with reactive bone as fibrous dysplasia. A-D, Low and intermediate power photomicrographs showing highly cellular variant of nonossifying fibroma composed of plump mononuclear cells with somewhat hyperchromatic nuclei. In such instances, correlation with a radiographic presentation of the lesion is helpful to avoid misclassification of hypercellular variants of nonossifying fibroma. A and B, Low and intermediate power photomicrographs showing hypercellular nonossifying fibroma. C and D, Low and intermediate power photomicrographs showing more typical presentation of nonossifying fibroma composed of fibrohistiocytic proliferation with intracytoplasmic deposition of hemosiderin. A-D, Low and intermediate power photomicrographs showing storiform fibrohistiocytic formations with prominent scattered multinucleated giant cells. B, Low power photomicrograph showing irregular hypocellular areas with stromal myxoid change. C and D, Low and intermediate power photomicrographs showing an area of reactive woven bone formation at the periphery of the nonossifying fibroma. Evans and Park12 reported three patients in the same family who had multiple nonossifying fibromas in long bones with many associated abnormalities. In both of these clinical syndromes, the nonossifying fibromas are found in the usual sites. More recent observations indicate, however, that Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome may represent a unique presentation of neurofibromatosis type 1 because some of these patients may have other stigmata of neurofibromatosis, such as cutaneous neurofibromas. In Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, the trunk, axial skeleton, and craniofacial bones are also typically involved. Each individual lesion has the radiographic appearance of a nonossifying fibroma, but occasionally each focus coalesces, especially in the metaphyseal parts, and forms a larger trabeculated lesion. Pathologic fracture frequently occurs in this syndrome, especially in younger patients. Similar to ordinary nonossifying fibroma, skeletal lesions in Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome have a tendency to stabilize and heal after puberty. The nonskeletal anomalies in this syndrome are hypogonadism, cryptorchidism, ocular anomalies, and cardiovascular malformations, including mitral insufficiency and aortic stenosis. Nonossifying fibromas in Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome have microscopic features identical to those seen in ordinary nonossifying fibromas. Microscopically, it is similar to the more common benign fibrous histiocytoma of soft tissue. In bone, it is microscopically indistinguishable from nonossifying fibroma or from the prominent fibrohistiocytic reaction found in some giant cell tumors. There is controversy about whether this is a distinct benign bone neoplasm or merely a reactive lesion superimposed on a preexisting condition that cannot be easily identified. Incidence and Location Benign fibrous histiocytoma is a very rare entity with strict radiologic and microscopic criteria. Patient age has a wide range from 5 to 75 years, and there is no clear sex predilection. Individual cases have been reported in flat bones, including the craniofacial bones, vertebrae, and sacrum. Clinical Symptoms the most frequent symptom is pain, ranging in duration from months to several years. Radiographic Imaging On radiographs, benign fibrous histiocytoma appears as a purely lytic, sharply demarcated lesion. The tumor can disrupt the cortex and expand into soft tissue, but usually it is delineated by a thin rim of newly formed bone. The reported cases located in the ends of long tubular bones are controversial because it is difficult, or perhaps even impossible, to exclude a giant cell tumor with a prominent fibrohistiocytic component. Microscopic Findings the spindle-shaped, fibroblast-like cells have elongated plump nuclei and small prominent nucleoli. A and B, Intermediate power photomicrographs show fibrohistiocytic lesion with storiform pattern. A and B, Anteroposterior radiographs of bilateral, multifocal nonossifying fibromas of humeri. A and B, Multiple, bilateral, lower-extremity long bone nonossifying fibromas in an 11-year-old boy with mental retardation, leg-length discrepancies, and skin pigmentation. Multinucleated giant cells are almost always present and are sparsely distributed among the other elements. Overall, the cellularity can be high with occasional hyperchromatic nuclei, but true nuclear atypia is absent. In the ribs, pelvis, skull, scapula, and vertebral column, such lesions may contain large amounts of lipids and may be referred to as xanthofibromas or xanthogranulomas of bone. Indeed, such lipid-filled lesions in ribs have been mistaken for localized lesions of Erdheim-Chester disease. Such areas sampled in small biopsy fragments may be interpreted as benign fibrous histiocytoma. The radiographic features of such cases are usually diagnostic for giant cell tumor of bone. Indeed, adequate sampling of a lytic tumor in the end of a long bone of an adult patient that shows "benign fibrous histiocytoma" features usually reveals small areas of classic giant cell tumor. The diagnosis of benign fibrous histiocytoma of bone is made by exclusion of other entities (eosinophilic granuloma, fibrous dysplasia, giant cell tumor, and giant cell reparative granuloma) that may exhibit prominent fibrohistiocytic reactions. Treatment and Behavior Benign fibrous histiocytoma should be treated by curettage and bone grafting. Recurrences can occur in the bone after curettage, but local aggressive behavior and particularly distant metastasis indicate that the diagnosis of benign fibrous histiocytoma was inappropriate. A, Well-marginated, radiolucent, asymptomatic lesion discovered on intravenous pyelogram of a 13-year-old girl. She had nephrectomy for a renal tumor at age 8, and follow-up studies revealed this lesion, samples of which were taken at subsequent biopsy. A, Oblique radiograph of foot of a 16-year-old boy with pathologic fracture through well-demarcated lytic lesion in calcaneus. B and C, Axial computed tomograms show lytic lesion with sclerotic borders and cortical infarction. Histologic features of benign fibrous histiocytoma closely resembling nonossifying fibroma were present in curettage specimen. In such cases, the characteristic radiographic features of a lytic lesion at the end of a long bone in a skeletally mature individual allow the inference to be drawn that the lesion is a giant cell tumor with secondary changes. This is analogous to making a diagnosis of giant cell tumor or any other bone lesion in which secondary aneurysmal bone cyst formation is so profuse that it obscures the precursor lesion. It is best to reserve the term benign fibrous histiocytoma for lesions that are indistinguishable from nonossifying fibroma but are located in unusual skeletal sites or present in older patients. The characteristic and unique feature is the frequent presence of general symptoms such as fever, anemia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and weight loss. Local lymphadenopathy was also present in two of our cases that presented as primary bone lesions. One lesion was originally diagnosed as nonspecific inflammatory reaction and recurred 3 months after initial curettage. Compterized imaging techniques can document the multilocular cystic nature of the lesion. Some investigators believe that these lesions represent variants of chondromyxoid fibroma. This lesion has been renamed angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma to reflect the relative rarity of metastasis and the overall favorable prognosis. Additional single case report of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma involving bone have been discussed in the literature. When it occurs in bone, the the microscopic appearance of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma of bone is similar to that described for soft tissue lesions. In fact, some lesions can be dominated by extensive multilocular cystic change that may obscure the details of the underlying lesion.

Mebendazole 100mg otc

Larger who hiv infection stages purchase 100mg mebendazole, thick-walled vessels can be seen within stromal bands separating tumor cells. The morphologic features of cells, and especially the details of the nuclei, are often Text continued on p. A Computed tomogram shows intramedullary tumor with cortical disruption posteriorly and extension into soft tissue. B and C, Anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographs show permeative lesion in metaphyseal region; so-called cortical saucerization (concave defect) can be seen on posterior surface in C. A, Large destructive tumor of body and glenoid regions of scapula with associated soft tissue mass. This atypical plain radiographic appearance was interpreted initially as probable vascular tumor. C, Expansile tumor with moth-eaten pattern of bone destruction in distal end of fibula in young adult. B, Radiograph of amputation specimen shows destruction of proximal plate of great toe and ill-defined soft tissue mass. C, Permeative destructive lesion involving entire shaft of proximal phalanx of finger is shown in this oblique radiograph. A, Lateral radiograph of ankle and foot of young adult shows rarefaction of posterior part of os calcis. B, Anteroposterior radiograph shows permeative destruction of cancellous bone with ill-defined border. C, Technetium 99 bone scan shows high uptake of isotope in os calcis, which is more intense posteriorly. Although distal tibia showed increased isotope uptake, tumor was not present in this site. A and B, Plain radiographs show destructive lytic mass of proximal tibia with increase of new periosteal bone formation. A and B, Coronal and sagittal computed tomograms showing a large tumor involving the upper portions of the left thoracic wall and pulmonary cavity. C and D, Axial and sagittal magnetic resonance images showing a large low signal intensity tumor involving the left paraspinal region and thoracic wall. Proximal circumferential soft tissue extension with elevation of periosteum is evident. Note large subperiosteal lesion with concave cortical surface; defect is referred to as saucerization. Intramedullary tan-gray tumor with posterior subperiosteal and soft tissue extension associated with concave cortical defect. C, Closer view of specimen shown in B shows intramedullary tumor with cortical permeation and periosteal elevation. Stroma is minimal and confined to few delicate fibrous tissue strands and blood vessels. D, Higher magnification of C shows uniform tumor cells with minimal amount of cytoplasm. Inset, High power photomicrograph of Homer Wright rosette consisting of a central fibrillar core bounded by concentrically arranged tumor cells. Note the presence of apoptotic dark cells at the interphase of viable and necrotic tumor. D, Higher magnification of the interphase between viable and necrotic tumor tissue showing prominent dark apoptotic cells. In a small number of tumors, the microscopic appearance of tumor cells may deviate from the so-called classic pattern. These features are more often seen in recurrent and treated lesions but can also be present in primary tumors. A delicate, finely granular chromatin pattern and clearly identifiable small to medium nucleoli are characteristic. Immunohistochemical and molecular study allowing differential diagnosis with other small cell malignances may be performed on material obtained for cytologic preparations. The cellularity is high, and the tumor cells are densely packed with almost nonexistent stroma. Two types of cells as defined by light microscopy-a principal type (light with open intact chromatin) and a secondary type (dark with condensed chromatin)-can also be recognized at the ultrastructural level. Minimal amounts of stromal elements associated with endothelial-lined capillaries and occasional larger vessels are seen focally. Centrally located nuclei are oval to round and have outlines with occasional indentations of the nuclear membrane. Some intracytoplasmic reticulum and poorly developed small Golgi centers are present. Ultrastructurally, there is a continuous transition from intact principal cells to dark apoptotic cells, and in some areas, the so-called dark cells can predominate. The ultrastructure of the dark cells may show all the features of nuclear condensation and segmentation described for apoptosis. Before the advent of chemotherapy, the prognosis was dismal, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 20%. The use of multimodality treatment plans of irradiation and multidrug chemotherapy plus surgery has significantly changed this survival rate. Those patients who initially have localized, resectable disease and are treated with multidrug chemotherapy in addition to surgery have a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70%. A-D, Fine-needle aspirate containing undifferentiated round cells with occasional nucleoli and indistinct cytoplasm, occasionally forming rosette-like structures (arrows). Inset, Rosettelike structure formed by circumferential arrangement of tumor cells around central core containing delicate fibrillar cytoplasmic material. A and B, Undifferentiated mesenchymal cells containing sparse cytoplasmic organelles and prominent deposits of glycogen. A, Undifferentiated tumor cells containing sparse cytoplasmic organelles and regular round nuclei with freely dispersed chromatin on occasional nucleoli. Similar to osteosarcoma, it has been shown that surgical removal of the resectable lung metastases improves survival. The incidence of disseminated disease at the time of diagnosis is high, and approximately 15% to 28% of patients initially have metastatic disease. Patients who have resectable lesions of the extremity bones have a better survival rate than those who have lesions affecting the trunk bones, such as the pelvis and the thoracopulmonary region. In addition, lesions in the latter sites are significantly larger at presentation and show extensive soft tissue involvement. Extensive spontaneous necrosis of untreated lesions is a predictor of more aggressive clinical behavior and is linked to lower survival rates. Its presence is considered by some authors to be synonymous with invasion into soft tissue and may signify a higher stage and volume of lesions. Favorable response, which is defined as total or subtotal (90% to 100%) necrosis, appears to be a strong predictor of long-term survival. The link between favorable prognosis and good chemotherapy response has been consistently shown in several independent studies. Moreover, the degree of postchemotherapy necrosis seems to correlate with the rate of disease-free survival. In a study from the Rizzoli Institute, the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 90% for patients with complete necrosis, 53% for those with microscopic residual tumors, and 32% for those whose lesions had gross evidence of residual tumor. Immunohistochemical features of overexpression of the genes involved in the development of drug resistance, such as P glycoprotein, show some promising results, but too few cases have been studied to assess the practical application of these findings. These types of rosettes should not be used as sole microscopic evidence of neural differentiation. Sparse neurosecretory granules are associated with both developing Golgi centers and cell processes. In a recent interinstitutional study involving several centers in the United States and Europe, the analysis of 315 cases showed no association between neural differentiation and more aggressive behavior.

Diseases

- Koone Rizzo Elias syndrome

- Leukomalacia

- Acrocephaly pulmonary stenosis mental retardation

- Neonatal ovarian cyst

- Deafness onychodystrophy dominant form

- Metabolic syndrome X

Discount mebendazole 100mg free shipping

In every case of lymphoma presenting as a bone lesion hiv infection window cheap 100 mg mebendazole free shipping, the appropriate staging procedure is required to rule out the presence of extraskeletal disease. The following discussion focuses on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and is based primarily on three published large series of primary lymphoma of bone including several histologic subtypes; however, in these series, at least 70%, 79%, and 83% of the cases were classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The humerus, ribs, and skull are next in frequency, and each is involved in approximately 10% of cases. The major long tubular bones, such as the femur and humerus, are the most frequently involved sites in the appendicular skeleton. The multifocality can be in the form of several foci within one bone, or several bones can be simultaneously affected. Other symptoms, such as nerve compression, are related to the location of the tumor. A general increase in incidence of cases from 1973 to 2006, similar to the increased incidence of lymphoma of all sites over this time period. Features of generalized systemic disease, such as lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, are not present at presentation by definition. Conflicting results have been published, with no clear advantage to radiation versus chemotheraphy alone versus combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Al remission, with approximately 75% survival at 400 months versus 0% survival in patients age 60 years or older. Patients with lymphoma limited to the bone have better survival than systemic lymphoma. The 5- and 10-year survival rates for primary bone lymphoma are 65% and 53%, compared with 53% and 43% for patients with systemic lymphoma in addition to bone masses. In long bones, the shaft is preferentially involved, and disease may extend to the end of the bone. Bone marrow involvement may be detected by T1-weighted (low signal) or T2-weighted (bright signal) magnetic resonance images. The cortex and the bone at its periphery show patchy erosions and permeation of the medullary cavity. Complete cortical disruption and extension into soft tissue are frequently present. Reactive sclerosis presents as firm ivory-like areas and may occasionally occupy a significant portion of the tumor. Microscopic Findings the conventional diffuse growth pattern with solid proliferation of round tumor cells permeating the bone marrow spaces and haversian canals is most frequently seen. In this pattern, the tumor cells are separated by dense fibrous bands and can form nests, cords, or organoid structures. A, Lateral radiograph of humerus of adult who complained of pain that had been present for several months. Permeative bone destruction with slight expansion of contour is noted over long segment of humeral diaphysis. B and C, Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of lower tibia and fibula of middle-aged adult show ill-defined destructive lesion in lower tibial shaft. Biopsy material removed several months earlier was erroneously interpreted as chronic osteomyelitis. Gene expression profiling is useful for subclassifying diffuse large B-cell lymphoma but is still not widely used in clinical practice. Exome or whole genome sequencing is becoming more widely available and likely will be one of the major tools used to identify actionable genetic alterations, allowing design and application of regimens, including specific targeted therapeutic agents. Immunohistochemistry remains a useful tool in the diagnosis and subclassification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lymphoma must be distinguished from other hematopoietic neoplasms, such as plasma cell myeloma, myeloid sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and mastocytosis. Once a diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is established, additional prognostic studies may be considered depending on the needs of the patient and treating physicians. A, Lateral radiograph of humerus showing a destructive mass with extensive involvement of the adjacent soft tissue. C, Oblique radiograph showing a destructive lytic lesion with soft tissue extension of the proximal ulna. A and B, Sagittally bisected tibia shows extensive gray-tan mass with extensive involvement of tibial shaft and adjacent soft tissue. Double hit and triple hit lymphomas are particularly aggressive lymphomas with poor prognosis and poor response to conventional chemotherapy. Multiple myeloma, especially the pleomorphic type, can resemble diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Review of serum and urine protein electrophoresis, if available, may help distinguish myeloma from lymphoma. In addition, immunohistochemical stains for and immunoglobulin chains are negative in most diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and positive in the vast majority of plasma cell myeloma cases. Eosinophilic myeloblasts, when present, are a clue to the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma. Three immunohistochemical stains approximate gene expression profile-based subtyping of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into germinal center subtype and non-germinal center subtype. This error can be avoided if attention is paid to the clinicoradiographic features. The involvement of the shaft of long tubular bones in patients older than age 40 years is rarely a feature of chronic osteomyelitis. The presence of reactive lymphocytes in malignant lymphoma is frequently responsible for this error. In this instance, the recognition of atypical lymphoid cells and the identification of the phenotypic features consistent with lymphoma are the keys to the correct diagnosis. Genetic Features and Pathogenesis the normal cell counterpart is a mature B cell that has been exposed to antigen and undergone somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes in the germinal center. The neoplastic B cells show clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes and show somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable chain genes, as is seen in normal germinal center and post-germinal center B cells. The molecular profile of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of bone is similar to that for the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurring at other sites. Subsequently, several groups have proposed algorithms based on more extensive immunohistochemical panels that slightly improve correlation between subgrouping based on gene expression-based and immunohistochemical features. It is estimated that an individual case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma harbors between 30 and 100 different mutations. Table 12-5 lists common genetic nature of the cells in question is often easier to recognize on touch preparations stained with Wright-Giemsa. Chloracetate esterase is inactivated by acid decalcification, and stains performed on decalcified tissue can provide false-negative results. Immunohistochemical stains for lysozyme myeloperoxidase are useful in identifying the myeloid nature of the tumor cells. Langerhans cell histiocytosis can be easily distinguished from lymphoma by the presence of a mixture of histiocytic cells with a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate. Occasionally, when Langerhans cells predominate, it can be difficult to distinguish Langerhans cell histiocytosis from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The strong positivity of Langerhans cells for S-100, the younger age of the patients, and radiographic features usually help distinguish this disorder from lymphoma. Mastocytosis can be suspected if the entire clinical presentation, the presence of skin lesions and systemic symptoms, is taken into consideration. The mast cell nature of the cells in question can be suspected if a round-cell infiltrate is negative for common leukocyte and epithelial markers. In one large study, exome sequencing of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas detected recurrent mutations in 322 genes.

Buy mebendazole without a prescription

In this protocol I measure volume of each bolus and present a range of materials from thin liquid to thick liquid to pudding hiv infection during menstruation generic mebendazole 100mg overnight delivery. If the patient can manage these materials, I may add cup or straw drinking and masticated materials. Conversely, for patients with specific symptoms (such as food sticking in the throat) who are ingesting a wide range of food and liquids by mouth, I use a different approach. These patients are examined in the standing position and given a cup with the various materials and asked to drink or eat as they would at home. Given patients who are eating and drinking a wide range of food and liquids, small volumes of measured materials would likely increase the duration of the examination (and hence the radiation exposure) and likely not reveal any difficulties until larger volumes or thicker materials are evaluated. Likewise, given patients with significant oropharyngeal dysphagia, large (uncontrolled) volumes of these same materials may increase risks of airway compromise. Sequencing the Events in the Fluoroscopic Study Different protocols have suggested different sequences of events during the fluoroscopic swallowing study. For example, Logemann12 recommends beginning with thin liquids in progressive sequential amounts (1 mL, 3 mL, 5 mL, 10 mL). Once thin liquid swallows are completed, pudding and then masticated materials are evaluated. However, this group did caution that larger, thicker, and masticated materials were given to patients only if they demonstrated adequate airway protection and pharyngeal clearance on the thin liquid materials. They concluded that the order of test materials did not affect the accuracy of safety of either imaging study. The author agrees that a standard protocol is beneficial when completing the fluoroscopic swallowing study, but recommends flexibility in the sequence of events to maximize the "diagnostic outcomes" for each patient. At least two approaches might be considered when sequencing materials during a fluoroscopic swallowing study. Both of these approaches typically begin with the patient seated and viewed from the lateral perspective. The first tasks typically are simple speech or phonation activities to facilitate an impression of movement of structures in the swallowing mechanism (lips, tongue, velum, and pharyngeal wall). In the standard sequence approach, unless there is significant dryness (xerostomia), weakness, or anatomic deviation in the oral cavity structures, the initial bolus is typically 5 mL of nectar-thickened liquid. The patient then is given a cup of thin liquid barium to drink freely and a masticated material coated with barium pudding (usually a cracker). Video 2-3 on the Evolve website shows examples of swallows of these and other materials by a healthy adult volunteer. Video 8-1 depicts examples of swallowing by patients with various dysphagia symptoms. After this sequence of events is imaged from the lateral view, the patient is turned and viewed from the anterior perspective. From this view the patient is asked to sustain phonation or repeat the same vowel to visualize movement of the true vocal folds. Some patients are asked to phonate in a falsetto mode to evaluate medial movement of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Some are asked to perform a "trumpet" maneuver to evaluate potential weakness in the lateral pharyngeal walls. The trumpet maneuver is accomplished by asking the patient to lift the chin to provide a clear view of the entire pharynx. Materials used in the anterior view depend largely on the results of swallows examined with the lateral view. In general, not all materials are repeated with the change in orientation, but sufficient swallows are evaluated to assess symmetry, physiology, and the consequences of impaired movement. Either before or after the evaluation of the swallow from the anterior view, compensatory maneuvers might be introduced to evaluate their effect on any observed impairments in swallow physiology. Common compensatory maneuvers include the chin-down position, head turn, supraglottic swallow, and Mendelsohn maneuver (see Chapter 10). The effects of these maneuvers can be evaluated in terms of improved swallow safety (less aspiration or penetration) or efficiency (better timing or less residue). If the patient cannot be positioned appropriately or if the risk of aspiration is too great, esophageal inspection is not added to the standard oropharyngeal examination. However, a cursory examination of the esophagus may be completed to rule out overt blockages or poor passage of material through the esophagus into the stomach. If the clinical presentation indicates potential for a significant esophageal-based dysphagia and the oropharyngeal examination does not identify any overt difficulties, a more thorough esophagram should be completed. Clinicians must decide how much of the standard protocol to complete for any given patient. Continuing to provide material to a patient who is aspirating a significant amount of each attempted bolus is unwise and contraindicated. Similarly, a study should not be continued if a patient becomes excessively fatigued or is otherwise unresponsive. Following a standard protocol blindly without consideration for the individual needs of the patient is poor practice. Box 8-5 lists the materials and sequence of presentation that may be included in a standardized fluoroscopic swallow study. The individualized sequence approach includes the same components as the standard sequence approach with the exception that the presentation of materials is patient performance dependent (see also Clinical Corner 8-1). For example, if 5 mL of nectar-thick liquid is the initial bolus and the patient does not aspirate but excessive residue is noted, the clinician might chose to use 5 mL of thin liquids as the next material to reduce the amount of residue and determine if airway protection is maintained. This includes smaller, measured amounts and self-selected volumes by spoon, cup, or straw. The difference in performance may be staggering for some patients, particularly those with cognitive or movement impairments attributable to neurologic deficits. Although in some cases this simple modification is not informative, in others this adjustment may make a large difference in patient performance and hence clinical interpretation of the videofluoroscopic swallow study results. What clinical disorders or impairments might contribute to an absent swallow initiation What neurologic or cognitive mechanisms might have an effect on a change in patient performance when self-feeding versus being fed What clinical implications would result when swallow performance does change when the patient engages in self-feeding Initial Bolus 5 mL nectar-thick liquid No Aspiration Excessive Residue 5 mL thin liquid No Aspiration Less Residue 10 mL thin liquid No Aspiration Less Residue 10 mL nectar-thick liquid No Aspiration Excessive Residue 5 mL pudding Aspiration 5 mL pudding No Aspiration Excessive Residue 5 mL nectar-thick liquid No Aspiration Less Residue 5 mL nectar-thick liquid No Aspiration Less Residue 5 mL thin liquid liquid. Conversely, if the initial bolus (5 mL of nectar-thick liquid) is aspirated, the next bolus might be 5 mL of pudding to determine if thicker materials are kept out of the airway. It is important to note that neither of these material sequence approaches has been empirically studied and thus it is unknown if one is superior to the other or if a completely different approach might be better than both of these options. They are presented here only for demonstration of options that clinicians might pursue during the fluoroscopic swallowing study. Beyond that caveat, the remaining components of this imaging study are recommended. What to Look For Despite recent attempts to "quantify" the interpretation of the videofluoroscopic swallowing study,23,27-30 the prevailing interpretation for this imaging examination is to describe various events associated with swallowing different materials. As noted with materials and sequencing of events during this examination, suggestions for interpretation vary across clinicians and authors. The following text presents a general approach to interpretation of the videofluoroscopic swallowing study. The "short form" of what to look for is anatomy and physiology underlying swallowing activity. This includes not only the oral cavity structures, velopharynx, pharynx, larynx, pharyngoesophageal sphincter, and cervical esophagus, but also the structure of the cervical spine. Depending on the clinical presentation of the patient, anatomy may be viewed from both lateral and anterior perspectives before any physiologic or swallowing assessment is initiated. The lateral view provides the best inspection of the movement within the swallowing mechanism. Box 8-6 summarizes the more salient observations obtained from both lateral and anterior views of the fluoroscopic study. Once the anatomy of the swallowing mechanism has been reviewed, basic movement patterns of structures within the swallowing mechanism should be evaluated without swallowing attempts.

Buy line mebendazole

In general hiv infection photos order discount mebendazole, this study is accomplished with the patient in an upright, seated position with adequate support for the head and body. Patients with physical limitations from weakness, fatigue, disease, or other reasons may require special positioning systems during the examination (see Practice Note 8-2). Various commercial positioning chairs are available to assist in optimal positioning of patients with physical limitations. Before purchasing or building a positioning chair, it is important to know the physical dimensions of the specific fluoroscopic system to be used. Often there is a fixed maximum distance between the table and tower of the fluoroscope. The selected chair or positioning system should be adaptable to accommodate both views. Finally, specifically for lateral views, large patients may not fit easily into the fixed space between the table and tower of the fluoroscope. In such cases, it is possible to turn the patient slightly toward an oblique orientation while maintaining a lateral perspective as much as possible. This perspective affords an excellent view of the swallowing mechanism from the lips to cervical esophagus and provides the best view of the trachea separate from the esophagus. After examination of the swallow in the lateral perspective, the patient is turned for an anterior view. This perspective permits excellent evaluation of symmetry along the swallowing mechanism. When the esophagus is imaged with the patient in a sitting position the extent of the view is often limited. In these situations, imaging is done with the patient in a standing or lying position depending on physical limitations of the patient or specific aspects of the dysphagia presentation. In fact, for some patients who can tolerate standing during the fluoroscopic examination without compromise, the entire examination can be done with the patient in a standing position. This situation permits a great degree of control in moving and positioning the patient. Material Used in the Fluoroscopic Study the key material used in the fluoroscopic swallow study is barium sulfate suspension. As a result, barium sulfate appears as black on the fluoroscopic image compared with negative contrast substances, such as air, which appear as varying shades of gray. Tissue and bone appear as shades of gray (darker than air) depending on their density. A popular point of discussion and even argument among clinicians is whether to use barium sulfate in isolation or in combination with real food items. No firm answer has emerged from these discussions and proponents of both perspectives have seemingly valid points. Individuals who focus on isolated barium products for this study claim that the range of food textures is so great that it would be impossible to image every possible food or liquid that a given patient might ingest. Another argument against using real food is the potential for complications resulting from aspiration of food products into the airway. Proponents of combining barium and real food items argue that barium products do not represent the consistencies noted in real food products. However, a study by Nagy, Steele, and Pelletier16 reported that adding barium sulfate to liquids did not significantly alter examined swallowing parameters. Although taste intensity was affected by the addition of barium, lingual-palatal pressures and surface electromyographic amplitudes were not significantly impacted. Interestingly, taste has been shown to affect swallowing characteristics (see Chapter 10) and a separate study by Dietsch et al. These studies present interesting observations that begin to address the food-versus-barium argument, but additional research will be needed including a wider range of swallowed materials. Regardless of the outcome of this food-versus-barium discussion, the importance of using a range of textures and volumes during the fluoroscopic swallowing study cannot be overstated. It is well known that a normal swallowing mechanism adjusts to changes in bolus volume and texture. Published literature suggests that approximately 20 mL of liquid represents the average drink from a cup. Therefore, based on a functional perspective, it seems reasonable that the majority of swallow attempts would include volumes somewhere within this range unless clinical indications exist to use less or more material. In fact, results of a recent study23 suggested that swallows of a 5-mL bolus of thin barium liquid and a 5-mL bolus of nectar-thick barium liquid contributed the greatest amount of information to interpretation of 15 physiologic swallowing components. This choice of volume and consistency is based in part on the functional considerations previously mentioned and in consideration of a study suggesting that when using standard materials, 5-mL and 10-mL volumes of thin and thick liquid demonstrated the strongest associations between clinical signs of aspiration and observed aspiration during the videofluoroscopic swallowing study. General categories of viscosity or textures include thin liquid, thickened liquid, paste or pudding, and masticated material. One benefit of these standardized barium products is consistency and reproducibility of repeated examinations both within and across patients. In short, use of standardized materials reduces variability across examinations that might result from use of different materials. One final consideration in choice of materials to include in the fluoroscopic swallow study is the nature of symptoms reported by the patient (see Practice Note 8-3). In comparing liquids (thin and thick), pudding, a barium tablet, and half a nonmasticated marshmallow, these investigators reported that the marshmallow provided the highest diagnostic yield for this particular symptom. Thus for some patients presenting specific symptoms a modified approach to the fluoroscopic swallowing evaluation might be indicated. For patients with clinically identified oropharyngeal dysphagia who may be rehabilitation candidates I use what I term the rehab fluoroscopic protocol. Typically this component of the examination is brief and involves short speech samples or vowel phonation. During these activities the clinician looks for appropriate movement of the lips, tongue, jaw, velum, larynx, and pharyngeal walls. Movement of the pharyngeal walls can best be evaluated by having the patient produce a falsetto phonation while viewed from the anterior perspective. The lateral pharyngeal walls typically move toward the pharyngeal midline with this maneuver. After assessment of the anatomy and basic movement capabilities of the swallowing mechanism, the clinician subsequently advances to a direct inspection of swallowing activity. Often the patient is asked to hold a bolus in the mouth before attempting to swallow (but see previous text on the potential effect of verbal cues with this strategy). This affords the opportunity to evaluate lip seal anteriorly and lingual-velar seal posteriorly. Impairment in these functions results in anterior spillage of the bolus or posterior spillage potentially into an open airway. If a solid bolus is used, clinicians should observe the patient masticate the food material, form a cohesive bolus, and propel this material into the oropharynx. In this pattern, the patient may deliver small amounts of masticated food into the pharynx while retaining the remaining food in the mouth for further preparation. Whether a liquid or solid bolus is used, the timing and efficiency of oral transit of the bolus should be documented. Poor temporal coordination of the oral component of swallowing might lead to entrance of material into an airway that has not yet closed. Alternatively, a prolonged oral component of swallowing may relate to prolonged mealtimes and thus reduced oral intake with increased nutritional risk for a patient. Reduced efficiency of oral transport might contribute to residue in and around the oral cavity after the swallowing attempt. Deficits in oral-nasal separation-whether from anatomic changes or physiologic deficits in velar movement patterns-can result in entrance of food or liquid into the nasal cavity. The hyoid bone and larynx typically move as a functional unit during swallowing attempts. Although extensive variation has been described in hyolaryngeal movement, most investigators and clinicians agree that the basic movement is upward and forward (elevation followed by anterior movement of both structures). Although this might seem to be a simple activity, appropriate movement of the hyolaryngeal complex involves adequate tongue base function and function of the muscles in the pharyngeal wall. As the larynx elevates, the tongue base moves posteriorly and inferiorly, the superior pharynx constricts, and the epiglottis retroflexes to assist in airway protection.

Buy mebendazole 100 mg amex

In general antiviral ilaclar trusted 100 mg mebendazole, this committee is composed of physicians, nurses, a psychologist or social worker, a chaplain, and a member from the community. Swallowing specialists or dietitians may be asked to be a part of the committee if the issues require their expertise. In some cases, a clinician who deals extensively with swallowing disorders is a member of the committee. First, the patient or family member is not convinced that they have received sufficient evidence to support the conclusions. Second, determinations of the best course of care, as well as who is the final arbiter making that decision, may not be clear. For example, the patient may have been told the best course of care by the attending physician but may have also received an opposing opinion from an outside consultant whom the patient trusts. Third, the medical care team and the patient may have personal biases that interfere with rational decision making. Finally, it may not be clear what the patient or surrogate considers a desirable outcome to the dilemma. In a large randomized control trial aimed toward providing information about decision making and feeding options in patients with dementia, surrogates who received training prior to the need to make decisions were better prepared and more comfortable with their decisions than those who received information about feeding options during a crisis situation. This study supports the need to involve caregivers early with patients who are at anticipated risk for severe dysphagia caused by progressive disease. The committee performs a thorough, nonbiased review of the medical and nonmedical risks associated with tube feeding in an effort to resolve the dilemma. This included a statement that he did not want to be fed through a tube in his stomach. His disease progressed to the point where he could not produce intelligible speech because of weakness in the muscles of articulation. He used an electronic communication board to compensate for the loss of communication skills. He continued to eat orally but choked violently at every meal as the nurses were feeding him. At the time of the consultation to speech pathology, he had been treated for six episodes of aspiration pneumonia in the previous 18 months. His videofluorographic swallowing examination showed aspiration on all bolus volumes and types, ranging from thin liquid to a semisolid. He was asked numerous times if he wanted to change his mind regarding the possibility of feeding tube placement to perhaps lessen the risk of developing pneumonia, but he refused. The patient did not have a family member in the vicinity who might have been available to provide feeding assistance. The ethics committee reviewed the entire medical history and established that the patient fully understood his medical condition. They found him competent to make decisions about his health based on the medical care team communications regarding the risks and benefits of continued oral feeding and those of tube feeding. It also was apparent that the nurses were not willing to cooperate with his feeding, leaving the patient at nutritional risk. After extensive discussion, the surgeon on the committee asked if it would be prudent to perform an elective laryngectomy, effectively separating the airway and food way to avoid the risk of aspiration. Because his speech was already unintelligible, it seemed like a reasonable option to sacrifice voice for swallow safety. One of the most commonly encountered dilemmas that the swallowing specialist faces is the patient who is known to aspirate and has decided that under no circumstances does he or she want a feeding tube. Furthermore, the physician may feel liable for legal action if aspiration pneumonia develops and the patient dies. These documents have not been challenged in the courts, so their validity remains questionable. However, because the medical record is a legal document, it is crucial that all conversations with the family about the risks and benefits of tube feeding, and the patient education they received on those issues, be thoroughly documented. The swallowing specialist whose evaluation might have helped the team make the decision that oral feeding was contraindicated also may believe that his or her professional ethics are at risk, particularly if asked to continue to assist the patient by providing the "safest" way to feed. In this case clinicians have the right to sign off the case and pass it to another colleague who may have a different perspective. In most cases the swallowing specialist provides additional care if convinced that the patient and family were fully informed of the continued risk and it was properly documented in the medical record. Furthermore, staying involved with the family and patient can allow for reassessment during times of change that may alter the original decision for oral or enteral feeding (review and discuss Clinical Corners 11-6, 11-7, and 11-8). Justify your answer based on how you evaluate the importance of each clinical finding. Only under ideal conditions did the modified barium swallow study show that the patient was not aspirating. The physician is worried that the family will place blame for a subsequent bout of pneumonia if the patient returns to oral feeding. What things does the family need to know and respond to that might affect the final decision He stopped eating, has lost 16 pounds, and his health will deteriorate unless a feeding tube is placed. He is ambulatory and responsive but is considered incompetent to understand his situation. Interestingly, his wife instructed the team to do everything possible to save his life at the time of the suicide attempt. Her refusal now is based on the fact that she says this is his way of saying he wants to die and she is honoring that wish. During his last hospitalization he had respiratory distress and a tracheostomy was performed. Although his prognosis was poor, he steadily recovered to the point that his physician wondered if he could once again eat orally. On swallowing trials of 5 and 10 mL of thin and thick liquid, the patient coughed on each bolus. Pudding pooled in the oral cavity but was swallowed with delay and postswallow cough. After asking questions about the definitions of aspiration and aspiration pneumonia, the daughter was not convinced he was aspirating because it could not be seen on a physical examination. She pressed the physician for a modified barium swallow study that she attended (Video 11-1 on the Evolve site). On multiple swallows penetration was noted; however, eventually the pharynx was cleared. On the final swallows of a pudding-thick bolus, the patient was able to swallow without delay or pharyngeal residue with only trace penetration. The patient started a soft mechanical diet but on the third day developed signs and symptoms consistent with aspiration pneumonia. Oral feedings were stopped while he was treated for suspected aspiration pneumonia. The daughter continued to argue for oral feeding and the team agreed to try again. This time he ate successfully for 5 days, and the decision was made to remove the tracheotomy tube. It is driven by a congressional mandate called the Patient Self-Determination Act. Feeding tubes do not necessarily reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia or prolong life. Some clinical factors are more predictive than others in identifying aspirators in whom pneumonia will develop. Ethical dilemmas regarding the use and acceptance of tube feeding may result in conflicts between the patient and the medical care team. Professional ethics can be threatened if a patient refuses to follow medical advice. Bourdel-Marchasson I, Dumas F, Pinganaud G, et al: Adult percutaneous gastrostomy in long-term enteral feeding in a nursing home. Bannerman E, Pendlebury J, Phillips F, et al: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study of health-related quality of life after percutaneous gastrostomy.