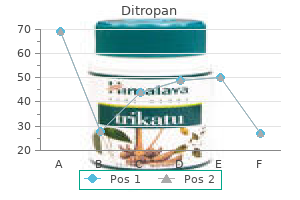

Order 2.5 mg ditropan

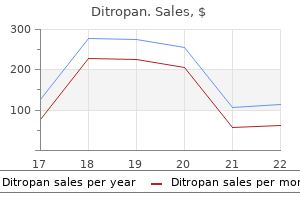

In patients having elective open abdominal aortic surgery gastritis zdravlje ditropan 2.5mg with visa, the use of postoperative epidural analgesia (especially thoracic epidural analgesia) resulted in better pain relief for up to 3 days after surgery, a reduction in duration of mechanical ventilation of 20%, and a lower risk of cardiovascular and renal complications compared with systemic opioid administration (215). Also compared with systemic opioids, epidural local anesthetics led to a reduction in the incidence of pulmonary complications and improved oxygenation (216). Multimodal Analgesia Multiple mechanisms, often coexisting, are involved in pain perception (219). It is, therefore, not surprising that treatment of pain may require multimodal strategies. Indeed, the use of multimodal analgesia in the treatment of acute pain should be the rule rather than the exception for most patients. The term multimodal refers to the use of a combination of drugs from more than one class of analgesic agent. The aim is to maximize the pain relief achieved, particularly dynamic pain, while minimizing the incidence of analgesia-related side effects (220). Multimodal analgesia should also be combined with multimodal and multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs to assist and speed patient recovery (220). Options for multimodal analgesia, therefore, include a variety of systemically and regionally administered analgesic agents. Only the systemic administration of analgesic drugs is covered in this chapter, as their use in regional analgesia is discussed in detail elsewhere in the book. However, a case control study of acetaminophen in relation to myocardial infarction found no such increased risk (238). In addition, it would seem that therapeutic doses of acetaminophen are unlikely to result in hepatotoxicity in patients who take moderate to large amounts of alcohol (235,240). Analgesic Drugs Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) Acetaminophen is an effective analgesic agent (221), but its exact mechanisms of action are yet to be clearly defined. It has also been suggested that part of the analgesic action of acetaminophen results from modulation of descending inhibitory serotonergic pathways (225). These two preparations have comparable efficacy but a higher incidence of local pain occurs at the infusion site with propacetamol (226,227). The onset of analgesia after propacetamol is shorter than after oral acetaminophen (228); compared with propacetamol, oral administration of acetaminophen results in a large and unpredictable variation in plasma concentration (229). Acetaminophen given as a regularly administered adjunct to opioid analgesia leads to significant opioid-sparing, but this may or may not improve pain relief, and does not reduce the incidence of opioid-related adverse effects. Again, a morphine-sparing effect of 20% was noted, but this was not associated with a reduction in morphine-related side effects. Acetaminophen is well-tolerated by most patients, giving rise to few adverse effects (221,235), and it is an important component of multimodal analgesia. Side effects of opioid analgesia have been discussed earlier (see section on Assessment and Monitoring). The key to effective analgesia with opioids is titration to effect for each patient. Therefore, to obtain good pain relief in individual patients, doses must be altered according to regular assessments of pain and adverse effects (particularly sedation), as discussed earlier. Differences may be seen between different opioids when given in conjunction with neuraxial analgesia (see Chapter 11). Tramadol is an effective analgesia agent and an effective treatment for neuropathic pain (61). In general, tramadol is less likely to cause respiratory depression (265,266), constipation (267), or delayed gastric emptying (268) than pure agonist opioids. A brief summary of side effects of epidural analgesia has been included earlier in this chapter. Regional Analgesia after Ambulatory Surgery the use of continuous peripheral nerve blocks for pain relief at home after ambulatory surgery was first described in 1998 (275) and followed the introduction of lightweight and portable infusion pumps. The technique has rapidly gained acceptance, and the literature pertaining to its use has grown markedly over just the last few years. The types of continuous peripheral nerve infusion that have been used include paravertebral, interscalene, infraclavicular, axillary, psoas compartment, femoral, sciatic, and tibial. A recent detailed review by Ilfeld and Enneking (276) summarized this relatively new information and highlighted some of the important issues to be considered when using these methods of pain relief at home. The benefits reported included improved pain relief, better sleep, lower opioid consumption, a decreased incidence of opioid-related side effects, and increased patient satisfaction (276). These authors also highlighted the need for appropriate patient selection, accurate catheter placement, firm fixation of the catheter, selection of a suitable infusion solution and infusion regimen (this will vary according to the anatomic site), and use of a reliable pump. Most importantly, they stress the need for verbal and written patient and caregiver information and education, and organization of patient contact and follow-up, as well as catheter removal. Local Anesthetic Agents Local anesthetic drugs are discussed in detail in Chapters 1 to 5. The topic is covered in detail in recent reviews (177,178,277), so a brief summary only will be included in this chapter. Later, in 1971, he described a machine that allowed patients to self-administer these bolus doses as needed (279). He found that this analgesic demand system provided better pain relief than fixed-dose, nurse-administered regimens. With the use of some disposable devices, the drug and drug concentration may be varied, but the volume of the bolus dose cannot be changed; in others, neither the drug administered nor the bolus dose delivered can be altered. The drug reservoirs for these devices are also more readily accessible, raising security issues. Possible opioid-related side effects have been covered in an earlier section of this chapter. Adjuvant Analgesic Drugs A number of other drugs are often given as adjuvant medications in the management of acute pain. A recent meta-analysis (62) of low-dose ketamine given in conjunction with opioid therapy has shown that it is opioid sparing and results in less nausea and vomiting, and adverse effects are either mild or absent. Although there is little evidence of any benefit of most antidepressant drugs on nociceptive acute pain (111), they may reduce the risk of development of persistent pain after surgery (see earlier discussion under Prevention Strategies). However, perioperative use of gabapentin can lead to significant reductions in postoperative pain intensity and analgesic use. All reported that gabapentin resulted in better pain relief and a reduction in opioid requirements; increased sedation was noted in two of the studies (270,271). Systemic administration of clonidine is also opioid-sparing (272) and improves pain relief (273). However, side effects such as sedation and hypotension can limit its usefulness in the clinical setting (111). Magnesium also improves pain relief and reduces postoperative opioid requirements (274). The use of adjuvant drugs with regional analgesia is discussed in other chapters in this book. The size of the bolus dose will need to be increased or decreased as needed according to subsequent reports of pain or the onset of any side effects (178). However, occasions will arise when these guidelines may not be as applicable to some patients as they will be to others, as a number of patient factors may also influence treatment. Patient Age Effect on Opioids Age, rather than patient weight, appears to be a better determinant of the amount of opioid an adult is likely to require for effective management of acute pain. The decrease in opioid requirement is not associated with reports of increased pain (288,290). As renal function inevitably declines with age, the elderly patient may also be at risk of accumulation of any active metabolites of opioids such as morphine, normeperidine, and dextropropoxyphene, and tramadol. For this reason, meperidine (300) and dextropropoxyphene (244) should be avoided in the elderly, and lower daily maximum dose limits of tramadol are suggested for patients older than 75 years (301). As noted earlier, there appears to be little difference in the side-effect profiles of different opioids at equianalgesic doses in most patients. However, in the elderly, fentanyl may cause less depression of postoperative cognitive function (302) and confusion (303). No difference in cognitive effects was seen in a comparison of fentanyl and tramadol in patients groups with average ages of 61 and 63 years, respectively (304).

Buy ditropan 5mg

Thalamic neurons responsive to temperature changes of glabrous hand and foot skin in squirrel monkey gastritis diet what to eat for breakfast lunch and dinner discount ditropan line. Responses of neurons in thalamic ventrobasal complex of rats to graded distension of uterus and vagina and to uterine suprafusion with bradykinin and prostaglandin F2 alpha. Wide-field neurons in somatosensory thalamus of domestic cats under barbiturate anesthesia. Distribution of responses to somatic afferent stimuli in the diencephalon of the cat under chloralose anesthesia. Ventral posterior thalamic neurons differentially responsive to noxious stimulation of the awake monkey. Neurons in ventrobasal region of cat thalamus selectivity responsive to noxious mechanical stimuli. Interactions between nucleus centrum medianum and gigantocellularis nociceptive neurons. Axonal transport and the demonstration of nonspecific projections to the cerebral cortex and striatum from thalamic intralaminar nuclei in the rat, cat and monkey. The medial pain system: neural representations of the motivational aspect of pain. The effect of peripheral stimulation on units located in the thalamic reticular nuclei. Alteration of activity of single neurons in the nucleus centrum medianum following stimulation of the peripheral nerve and application of noxious stimuli. Descending serotonergic, peptidergic and cholinergic pathways from the raphe nuclei: a multiple transmitter complex. Failure to find homology in rat, cat, and monkey for functions of a subcortical structure in avoidance conditioning. Effects of cortical and thalamic lesions on temperature discrimination and responsiveness to foot shock in the rat. Medial thalamic lesions in the rat: effects on the nociceptive threshold and morphine antinociception. Centrum medianumparafasicularis lesions and reactivity to noxious and non-noxious stimuli. Effect of medial thalamic lesions on responses elicited by tooth pulp stimulation. The effect on reaction to painful stimuli of lesions in the centromedian nucleus in the thalamus of the monkey. Experimental local thalamic application of xylocaine through silicone rubber chemode. Central neural mechanisms that interrelate sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Projection of different spinal pathways to the second somatic sensory area in cat. Sensory, motivational and central control determinants of pain: A new conceptual model. Radiofrequency cingulotomy for intractable cancer pain using stereotaxis guided by magnetic resonance imaging. The affective component of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in rats subjected to intense electrical and noxious chemical stimulation of the forepaw. Dissociating anxiety from pain: mapping the neuronal marker N-acetyl aspartate to perception distinguishes closely interrelated characteristics of chronic pain. The effects of failure feedback and pain-related fear on pain report, pain tolerance, and pain avoidance in chronic low back pain patients. Activation of a local spinal inhibitory system by focal stimulation of the lateral Lissauer tract in cats. On the organization of the supraspinal inhibitory control of interneurones of various spinal reflex arcs. Supraspinal inhibitory control of transmission to three ascending spinal pathways influenced by the flexion reflex afferents. Inhibition of spinothalamic tract cells and interneurons by brain stem stimulation in the monkey. Inhibition in spinal cord of nociceptive information by electrical stimulation and morphine microinjection at identical sites in midbrain of the cat. Quantitative comparison of inhibition in spinal cord of nociceptive information by stimulation in periaqueductal gray or nucleus raphe magnus of the cat. Studies on the site of analgesic action of morphine by intracerebral microinjection. Inhibitory effects of nucleus raphe magnus in neuronal responses in the spinal trigeminal nucleus to nociceptive compared with nonnociceptive inputs. Descending influences of periaqueductal gray matter and somatosensory cerebral cortex on neurones in trigeminal brain stem nuclei. Pain reduction by focal electrical stimulation of the brain: An anatomical and behavioral analysis. Chapter 32: Physiologic and Pharmacologic Substrates of Nociception after Tissue and Nerve Injury 749 698. Analgesia induced by electrical stimulation of the inferior centralis nucleus of the raphe in the cat. Characterization of the spinal adrenergic receptors mediating the spinal effects produced by the microinjection of morphine into the periaqueductal gray. Antagonism of stimulation-produced antinociception by intrathecal administration of methysergide or phentolamine. Inhibition by etorphine of the discharge of dorsal horn neurons: effects on the neuronal response to both high- and low-threshold sensory input in the decerebrate spinal cat. Efflux of 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline into spinal cord superfusates during stimulation of the rat medulla. Selective reduction by noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine of nociceptive responses of cat dorsal horn neurones. Monoamine release from cat spinal cord by somatic stimuli: an intrinsic modulatory system. Factors governing release of methionine enkephalin-like immunoreactivity from mesencephalon and spinal cord of the cat in vivo. Evidence for cholecystokinin-like-immunoreactive neurons in the rat medulla oblongata which project to the spinal cord. Combined immunocytochemistry and autoradiography after in vivo injections of monoclonal antibody to substance P and 3H-serotonin: Coexistence of two putative transmitters in single raphe cells and fiber plexuses. Analgesia produced by mesencephalic stimulation: Effect on bulboreticular neurons. Comparison of antinociceptive action of morphine in the periaqueductal gray, medial and paramedial medulla in rat. Examination of spinal monoamine receptors through which brainstem opiate-sensitive systems act in the rat. Diencephalic connections of the raphe nuclei of the rat brainstems: An anatomical study with reference to the somatosensory system. Dorsal raphe stimulation reduces responses of parafasicular neurons to noxious stimulation. Raphe induced inhibition of intralaminar thalamic unitary activities and its blockade by para-chlorophenylalanine in cats. Electrical stimulation of the central gray for pain relief in humans: A critical review. Inhibition of nonspecific sensory activities following striopallidal and capsular stimulation. Effects of dorsal rhizotomy on the autoradiographic distribution of opiate and neurotensin receptors and neurotensinlike immunoreactivity within the rat spinal cord. The effects of intrathecally administered opiod and adrenergic agents on spinal function. Basic and regulatory mechanisms of in vitro release of Met-enkephalin from the dorsal zone of the rat spinal cord. Studies on the release by somatic stimulation from rat and cat spinal cord of active materials which displace dihydromorphine in an opiate-binding assay. Peptidases prevent mu-opioid receptor internalization in dorsal horn neurons by endogenously released opioids. Endogenous pain inhibitory systems activated by spatial summation are opioid-mediated.

| Comparative prices of Ditropan | ||

| # | Retailer | Average price |

| 1 | Subway | 374 |

| 2 | SonyStyle | 419 |

| 3 | Dell | 609 |

| 4 | Family Dollar | 773 |

| 5 | Limited Brands | 795 |

| 6 | Dick's Sporting Goods | 217 |

Order ditropan 2.5mg line

Perceptual changes accompanying controlled preferential blocking of A and C fibre responses in intact human skin nerves gastritis low carb diet buy ditropan toronto. Afferent C units responding to mechanical, thermal and chemical stimuli in human non-glabrous skin. Excitation failure in thin nerve fiber structures and accompanying hypalgesia during repetitive electric skin stimulation, Advances in Neurology. Tactile sensibility in the human hand: receptive field characteristics of mechanoreceptive units in the glabrous skin area. Stimulus-response functions of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors in the human glabrous skin area. Stimulus-response functions of slowly adapting mechanoreceptors in the human glabrous skin area. Human C fiber input during painful and nonpainful skin stimulation with radiant heat. Role of large diameter cutaneous afferents in transmission of nociceptive messages: Electrophysiological study in man. The effect of carrageenan-induced inflammation on the sensitivity of umyelinated skin nociceptors in the rat. Experiments relating to cutaneous hyperalgesia and its spread through somatic nerves. Local oedema and general excitation of cutaneous sensory receptors produced by electrical stimulation of the saphenous nerve in the rat. The components of the dorsal root mediating vasodilatation and the Sherrington contracture. Fatigue and adaptation in unmyelinated (C) polymodal nociceptors to mechanical and thermal stimuli applied to the monkey face. The sensitization of high threshold mechanoreceptors with myelinated axons by repeated heating. Protons selectively induce lasting excitation and sensitization to mechanical stimulation of nociceptors in rat skin, in vitro. Possible role of arachidonic acid and its metabolites in mediator release from rat mast cells. The effect of histamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine and acetylcholine on cutaneous afferent fibres. Action of peptides and other algesic agents on paravascular pain receptors of the isolated perfused rabbit ear. Visceral pain and the pseudaffective response to intra-arterial injection of bradykinin and other algesic agents. Capsaicin inhibits responses of fine afferents from the knee joint of the cat to mechanical and chemical stimuli Brain Res 1990;530:147. Inflammatory mediators and nociception in the joint: Excitation and sensitization of slowly 137. Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as inhibitors of phospholipase A2 New York, Raven Press, 1978. The role of lipids in platelet function with particular reference to the arachidonic acid pathway. Release of histamine, kinin and prostaglandin during carrageenininduced inflammation in the rat. Release of prostaglandins from the isolated perfused rabbit ear by bradykinin and acetylcholine. Release of prostaglandins by bradykinin as an intrinsic mechanism of its algesic effect. Inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis as the mechanism of analgesia of aspirin-like drugs in the dog knee joint. Hyperalgesia after treatment of mice with prostaglandins and arachidonic acid and its antagonism by antiinflammatory-analgesic compunds. Influences of algogenic substances and prostaglandins on the discharges of unmyelinated cutaneous nerve fibers identified as nociceptors, Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. The effects of bradykinin and prostaglandin E1 on rat cutaneous afferent nerve activity. Adenosine injection into the brachial artery produces ischaemia like pain or discomfort in the forearm. The role of interleukins and nitric oxide in the mediation of inflammatory pain and its control by peripheral analgesics. Bradykinin initiates cytokine-mediated inflammatory hyperalgesia Br J Pharmacol 1993;110:1227. Chapter 32: Physiologic and Pharmacologic Substrates of Nociception after Tissue and Nerve Injury 741 171. Intrathecal protease-activated receptor stimulation produces thermal hyperalgesia through spinal cyclooxygenase activity. Decrease of substance P in primary afferent neurones and impairment of neurogenic plasma extravasation by capsaicin. Experimental immunohistochemical studies on the localization and distribution of substance P in cat primary sensory neurones. Substance p: localization in the central nervous system and in some primary sensory neurons. Perivascular meningeal projections from cat trigeminal ganglia: Possible pathway for vascular headaches in man. Neurotransmitters and the fifth cranial nerve: Is there a relation to the headache phase of migraine Immunoreactive tachykinins, calcitonin gene-related peptide and neuropeptide Y in human synovial fluid from inflamed knee joints. Tissue concentration and release of substance P-like immunoreactivity in the dental pulp. Immunoreactive substance P release from skin nerves in the rat by noxious thermal stimulation. Pharmacology of the effects of bradykinin, serotonin, and histamine on the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from C-fiber terminals in the rat trachea. Thin-fibre receptors responding to mechanical, chemical, and thermal stimulation in the skeletal muscle of the dog. Excitation of cutaneous afferent nerve endings in vitro by a combination of inflammatory mediators and conditioning effect of substance P. Direct evidence for neurogenic inflammation and its prevention by denervation and by pretreatment with capsaicin. Functional and fine structural characteristics of the sensory neurone blocking effect of capsaicin. Studies on the trigeminal antidromic vasodilatation and plasma extravasation in the rat. Inhibition of anhdromic and substance P-induced vasodilatation by a substance P-antagonist. Myelinated afferent fibers responding specifically to noxious stimulation of the skin. Functional properties of primary afferent units probably related to pain mechanisms in primate glabrous skin. Myelinated afferent fibers innervating the primate skin and their response to noxious stimuli. Neural correlates of escape behavior in rhesus monkey to noxious heat applied to the face. Comparison of responses of warm and nociceptive C-fiber afferents in monkey with human judgements of thermal pain. Peripheral suppression of first pain and central summation of second pain evoked by noxious heat pulses. Work-induced potassium changes in skeletal muscle and effluent venous blood assessed by liquid ion-exchanger microelectrodes. A critical review of the afferent pathways and the potential chemical mediators involved in cardiac pain. Studies on the relation of the clinical manifestations of angina pectoris, coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction to the pathological findings, with particular reference to the significance of the collateral circulation. The surgical relief of severe angina pectoris: Methods employed and end results in 83 patients.

Ditropan 2.5mg discount

The conditioning mechanism has gained support through a variety of trials both in animals (12 gastritis bad breath generic 2.5mg ditropan,13) and humans (14,15). A recent study demonstrated that placebo analgesic responses were able to be conditioned using both opiate and nonopiate drugs (16). This study also looked at expectancy mechanisms and found that the placebo analgesic response was greatest when both conditioning and expectancy were involved. One study was able to demonstrate the conditioning mechanism in a clinical population (20). In this study, patients were given standard postoperative analgesia, and ventilatory function was monitored. In this study, the placebo was able to cause a "side effect" similar to that of the active drug. More recent work has also shown that the conditioning mechanism, particularly when involving unconscious processes, such as hormone secretion (18) and immune responses (21,22), may contribute to placebo effects. In the case of placebo analgesia, it would seem that the expectancy mechanism plays a significant role and may be integrated with the conditioning process. The expectations of the patient regarding the treatment being administered, also termed response expectancies, are those held by an individual about his automatic emotional and physiological responses to a particular stimulus (23,24). These studies have shown that expectations are powerful contributors to placebo responses, particularly the placebo analgesic response. Neurobiologic Mechanisms the neurobiologic mechanisms of the placebo response were highlighted for the first time in 1978, by Levine, Gordon, and Fields, who showed that placebo analgesia was reversed by the administration of naloxone, an endogenous opioid antagonist, suggesting a role of endogenous opioids in the placebo analgesic response (30). The majority of research into the neurobiologic mechanisms of the placebo response has looked at the role of endogenous opioids, although in some studies naloxone has had no effect on placebo analgesia (16,31,32). The occurrence of both positive and negative results for the effects of naloxone suggests that placebo analgesia is mediated by both opioid and nonopioid mechanisms. One interesting example of the variable role of endogenous opioids is the study by Amanzio and Benedetti in 1999 (16). Placebo analgesic responses were seen following conditioning with both these drugs, and the responses in the expectancy groups were reversed by naloxone, demonstrating that the expectancy mechanism is mediated by endogenous opioids. This variability demonstrates that different mechanisms (both opioid and nonopioid) are involved in the placebo response and that the drug used to condition the response plays a role in the mechanism of the response. The role of endogenous opioids has been supported by numerous experiments that have indicated that naloxone can fully (33,34) or partially (35) reverse placebo analgesia, including placebo analgesia elicited through expectation and opioid conditioning (16,25). Interestingly, naloxone is able to reverse spatially or target-specific placebo analgesia in specific parts of the body, suggesting a somatotopic organization of endogenous opioid systems at the level of higher centers in the brain (25). This is a particularly important finding as it demonstrates that the placebo analgesic response acts through release of endogenous opioids at a variety of sites in the nervous system that are involved in the experience of pain. The reversal of placeboinduced respiratory depression (20), decreased heart rate, and decreased -adrenergic response (36) indicates that the opioid mechanisms of the placebo response also act on other regions and neural circuits, such as the respiratory and cardiovascular centers. Further interesting examples of the involvement of other neurochemical systems are seen in other recent studies. In one study, preconditioning with a serotonin agonist (sumatriptan) prior to placebo administration resulted in placebo-induced increases in plasma growth hormone and decreases in cortisol (18). Studies of the placebo response in Parkinson disease have added to our understanding of the neurobiology of the placebo response. In Parkinson disease, placebo administration can lead to an increase in dopamine in the ventral (37) and dorsal striatum (38) of sufferers, and this increase in dopamine correlates with improvement in motor function (38). Electrophysiologic evidence has also shown improvements in motor function, along with placebo-induced changes in subthalamic nucleus neuronal activity (39). Parkinson disease has thus emerged as an interesting model to study the placebo response, particularly in light of the increasingly evident anatomic and biochemical relationship between reward and opioid circuitry. Advances in imaging technology have allowed the investigation of regional brain activation during the experience of pain and during the placebo analgesic response. These areas encompass the neural pathways believed to be responsible for the sensory, affective, and evaluative dimensions of the pain experience. This pattern of activation, termed the pain matrix, corresponds to the neuronal substrate of multiple dimensions of pain according to the neuromatrix model described by Katz and Melzack in Chapter 35. It was found that the same regions in the brain activated by the opioid injection were also activated by the placebo injection. This study supported the findings of the just described study, showing that activity in the areas involved in the pain matrix decreased upon placebo intervention, again particularly in those areas rich in opioid receptors and involved in the descending pain inhibitory system. These studies offer insights into the role of psychological and neurobiologic mechanisms in altering the processing of pain in the brain, both in sensory, affective, and evaluative dimensions (43). In fact, it is now evident that multiple psychobiologic responses follow administration of a placebo depending upon the drug compared with placebo and other factors, and therefore there exists not one placebo response but many. In the case of placebo analgesia, it is evident that expectations and the endogenous opioid system play a significant role in altering nociceptive processing. Novel techniques, such as those described earlier, provide important information about the functional neuroanatomy of the placebo response. The integration of imaging and biochemical studies should further enhance our knowledge about the psychobiologic underpinnings of the placebo response. The first is hidden administration, in which the patient is unaware when he receives the drug, and side effects that can provide such cues are minimal. Hidden administration removes the expectation component and other "context effects" from the treatment, implying that the observed response is primarily due to the pharmacologic action of the drug alone. The second is open administration, which resembles clinical practice in which an injection is given by the clinician in full view of the patient. Interestingly, many drugs are far less effective when patients do not know they are receiving them (55,56). In other words, removal of the expectation component and the context effects surrounding the injection contributes to a diminution of the response to the drug. In some cases, the drug may actually have little or no effect when given by hidden administration (56,57). A clinical trial conducted by one of us in 1995 illustrates the importance of open administration. The greater the difference between the response to placebo and the response to the active drug, the more efficacious the drug is deemed to be. In this particular trial, the group taking proglumide showed significantly more analgesia compared with the placebo group, indicating that proglumide was an effective analgesic. It therefore appeared that proglumide had no specific analgesic properties (contrary to the result of the standard placebo-controlled trial), yet was able to potentiate analgesia through placebo-activated endogenous opioid mechanisms. First, this paradigm may be useful to assess the true pharmacologic action of some drugs (1,55,59). It is clear that a significant proportion of this difference results from the expectation component of the treatment. This paradigm therefore allows separation of the effect of a treatment from the context or environment in which the treatment is given. Amazingly, the perceived assignment of treatment had a more powerful effect upon clinical outcome than did the actual assignment. This perception and concomitant patient expectations had a significant effect on both psychological (quality of life) and physiologic (motor function) outcomes, regardless of whether the patient actually received placebo or active treatment. The results of the above study have been replicated in a trial of acupuncture analgesia (64). In this study, the perceived assignment to receive sham or true acupuncture better predicted the analgesic response than did the actual assignment, again highlighting the power of expectations in responses both to active and placebo treatments. A recent study has further extended these findings, in that perceived assignment to nicotine replacement or placebo better predicted the outcome (cessation of smoking) than did actual allocation (65). The power of expectation and potentially exploitable placebo mechanisms is demonstrated in two different studies involving drug administration. One study examined the effects of expectation on regional brain metabolic activity following administration of a stimulant drug (66).

Buy 2.5mg ditropan fast delivery

In spinal analgesia gastritis diet tips ditropan 2.5 mg sale, the sympathetic blockade starts at a level much more caudal than that of analgesia, in contrast to what has historically been stated in the literature (45). This partial sympathetic blockade, however, disappears much earlier than the analgesia, in most cases starting 20 to 40 minutes after the injection of the spinal anesthetic. Similar results have been seen when the skin blood flow has been studied with the help of laser Doppler flowmetry (14,15). A very high spinal analgesia is thus needed to make sure that marked depression of sympathetic activity in the lower extremity is produced. The increase in limb blood flow resulting from epidural block has been clinically related to a lower incidence of postoperative deep venous thrombosis (see Chapter 11). This effect is most likely correlated with an increase in cardiac output, provoked by the local anesthetic itself (see Chapters 2, 4, and 11). The limited blocking of sympathetic fibers produced by epidural blockade also explains the fact that a very high epidural blockade is required to ablate stress responses during and after lower abdominal surgery. Skin blood flow is similar (2 mL/100 mL/min) in both limbs, and the response to ice (arrow) is a similar reduction in the height of the pulse wave in both limbs. The blocked limb (right) shows a marked increase in the slope of the upward deflection of the pulse wave and an increase in height of the pulse wave; this reflects a tenfold increase of skin blood flow to 22 mL/100 mL/min. In contrast, the unblocked limb (left) shows the same shape and height of the pulse wave, and there is a similar marked reduction in blood flow (40% decrease) in response to ice. The foot is enclosed in a constant-temperature water bath, which surrounds a plethysmograph attached to a pressure transducer. Application of ice to the side of the neck results in a marked increase in sympathetic tone, with a decrease both in the upslope and in the area under the curve. Blood flow, sympathetic activity, and pain relief following lumbar sympathetic blockade or surgical sympathectomy. The latter can be rendered much more complete if a splanchnic blockade is added (see Chapter 6). Proper selection of patients for sympathetic blockade is obviously of great importance. Because the number of patients with vascular disease is very large, complicated and timeconsuming physiologic studies are not always feasible. The use of continuous catheter sympathetic blockade that lasts for 5 days is one method of obtaining a clinical evaluation of the effect of such blockade, which should at least identify patients whose symptoms are exacerbated by blockade (47). Pain score (mean on 10-cm analogue scale) prediagnostic and postdiagnostic local anesthetic (bupivacaine) and neurolytic (phenol) sympathetic blockade in 47 and 26 patients, respectively. Blood flow, sympathetic activity and pain relief following lumbar sympathetic blockade or surgical sympathectomy. D diagnostic block with long-acting local anesthetic mixed with contrast medium, and then check the adequacy of sympathetic chain coverage under an image intensifier; however, this has proved the least reliable of the three (16,39). Increased walking tolerance (seven of 16, or 44%) was a significant benefit in a small group of patients with intermittent claudication. Sympathetic blockade was part of a general treatment program that included mobilization and wound treatment, and sometimes infusion of low-molecular-weight dextran. However, Cousins and colleagues (16) reported that duration of relief of rest pain was similar to duration of lumbar sympathetic blockade, strengthening the link between pain relief and sympathetic denervation. Blood flow distribution after lumbar sympathetic blockade in arteriosclerotic patients at rest. Blood flow in the femoral artery (electromagnetic flow meter) is increased, as is skin blood flow (skin temperature); however, muscle blood flow (133 Xe clearance) is reduced. Graft muscle skin blood flow after epidural block in vascular surgical procedures. An arterial obstruction in branch B will increase the resistance and thus hamper the blood flow. An increased flow through collaterals (Collat) may compensate for a fall in blood flow through the main channel. Another study indicated that nutritive blood flow was not increased, but pain was relieved in a high percentage of patients (50). Very little data are available on upper limb vascular disease, although case reports indicate beneficial results with sympathetic block in vasospastic disorders such as those listed in Table 39-1. It would appear that the primary benefits that result from sympathetic blockade are pain relief and improved healing of skin lesions; however, controlled studies of efficacy of the sym- Application for Pain Relief other than in Occlusive Vascular Disease the pain-relieving effect of a sympathetic block in a patient with peripheral arterial disease is said to follow improved blood flow. The precise mechanism whereby the nervous system is involved in peripheral pain independent of effects upon flood flow have not yet been fully elucidated (11). A limited sympathetic blockade of fibers to branch B alone will little affect perfusion pressure. In branch C, the flow will be slightly reduced as compensatory vasoconstriction occurs. The blood flows through an artery (A) or its branches (B and C) are proportionate to the perfusion pressures and inversely proportionate to total and regional resistances, respectively. A widespread sympathetic blockade of fibers to branches B and C will diminish resistance in undamaged vessels (C), thereby potentially stealing blood from a diseased part (B) of the vascular tree. A vasodilatation restricted to branch B and its collaterals (Collat) and vessels beyond the arterial obstruction should increase blood flow to this region. Interruption of this feedback loop may explain the often remarkable pain relief seen after sympathetic blocks in patients with threatening gangrene, despite a lack of improvement in skin blood flow. It is possible that increased efferent sympathetic activity increases activity in nocireceptors by way of sympathetic fibers in proximity to sensory receptors. Although such mechanisms have long been suspected, this observation proves that it in fact does occur in patients with chronic pain. Such sympathetically maintained pain is not always present in neuropathic pain conditions. Although a history of pain that is aggravated by cold or anxiety may indicate the presence of components of sympathetically maintained pain, only an effective sympathetic blockade can determine the presence of such pain. Some clinical observations also indicate that early herpes zoster pain and healing of skin vesicles are improved by sym- pathetic blockade (see Chapter 42) (54,55). That this condition also responds well to a block of the appropriate somatic nerve is well established, so that it is uncertain whether any specific sympathetic involvement is present in this condition. Results of sympathetic block in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia are uniformly disappointing. These fibers are better classified as visceral nociceptive afferents, leaving sympathetic fibers only as efferents. Painful and nonpainful stimuli are also transmitted via ("sympathetic") visceral afferent nerve fibers (about 15,000) in dorsal nerve roots to spinal cord, travelling in the hypogastric, lumbar sympathetic, minor and major splanchnic, and cardiac nerves. Sacral part of the spinal cord also receives visceral afferents ("parasympathetic") from pelvic organs via the sacral nerves and their dorsal root ganglion. General functions of afferent visceral neurons are indicated in the right column; see also the following two figures. The pain of uterine contractions during the first stage of labor is effectively relieved by extradural sympathetic blockade (see Chapter 24).

Syndromes

- Albuteral--a drug used for people with asthma

- A drug that lowers levels of calcium in the blood (gallium nitrate)

- Breathing problems

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Anemia

Purchase 5mg ditropan fast delivery

Effect of pre-emptive ketamine on sensory changes and postoperative pain after thoracotomy: Comparison of epidural and intramuscular routes gastritis dietz order discount ditropan. A randomised double blind trial of the effect of pre-emptive epidural ketamine on persistent pain after lower limb amputation. The effects of intrathecal cyclooxygenase-1, cyclooxygenase2, or nonselective inhibitors on pain behavior and spinal fos-like immunoreactivity. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: An update for clinicians: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Role of nitric oxide in the development of thermal hyperesthesia induced by sciatic nerve constriction injury in the rat. Allodynia evoked by intrathecal administration of prostaglandin F2a to conscious mice. Evoked release of amino acids and prostanoids in spinal cords of anesthetized rats: Changes during peripheral inflammation and hyperalgesia. Antinociceptive actions of spinal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the formalin test in the rat. Nociceptive effects induced by intrathecal administration of prostaglandin D2, E2, or F2alpha to conscious mice. The spinal and peripheral roles of bradykinin and prostaglandins in nociceptive processing in the rat. Spinal adenosine modulates descending antinociceptive pathways stimulated by morphine. Interdependence of spinal adenosinergic, serotonergic and noradrenergic systems mediating antinociception. Antinociception induced by intrathecal coadministration of selective adenosine receptor and selective opioid receptor agonists in mice. Behavior induced by putative nociceptive neurotransmitters is inhibited by adenosine or adenosine analogs coadministered intrathecally. Phase I safety assessment of intrathecal injection of an American formulation of adenosine in humans. Intrathecal adenosine administration: A phase 1 clinical safety study in healthy volunteers, with additional evaluation of its influence on sensory thresholds and experimental pain. The safety and efficacy of intrathecal adenosine in patients with chronic neuropathic pain. Substance P markedly potentiates the antinociceptive effects of morphine sulfate administered at the spinal level. Inhibition of morphine tolerance development by a substance P-opioid peptide chimera. An assessment of the interaction between cholecystokinin and the opiates within a drug discrimination procedure. Descending control of pain in the enhanced potency of spinal morphine following carrageen in inflammation. The cholecystokinin receptor antagonist devazepide enhances morphine-induced analgesia but not morphine-induced respiratory depression in the squirrel monkey. Comparison of extradural administration of sufentanil, morphine and sufentanil-morphine combination after caesarean section. Isobolographic superadditivity between delta and mu opioid agonists in the rat depends on the ratio of compounds, the mu agonist and the analgesic assay used. Lesions of the dorsolateral funiculus block supraspinal opioid delta receptor mediated antinociception in the rat. Supraspinal and spinal delta(2) opioid receptor-mediated antinociceptive synergy is mediated by spinal alpha(2) adrenoceptors. Differential right shifts in the dose-response curve for intrathecal morphine and sufentanil as a function of stimulus intensity. Minimum effective combination dose of epidural morphine and fentanyl for post-hysterectomy analgesia: A randomized, prospective, double-blind study. Enhanced pain management for postgastrectomy patients with combined epidural morphine and fentanyl. Comparison of epidurally administered sufentanil, morphine, and sufentanil-morphine combination for postoperative analgesia. Epidural fentanyl, adrenaline and clonidine as adjuvants to local anaesthetics for surgical analgesia: Meta-analyses of analgesia and side-effects. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Current practices in intraspinal therapy: A survey of clinical trends and decision making. Antinociceptive synergy between intrathecal morphine and lidocaine during visceral and somatic nociception in the rat. Intrathecal coadministration of bupivacaine diminishes morphine dose progression during long-term intrathecal infusion in cancer patients. Patient-controlled extradural analgesia with bupivacaine, fentanyl, or a mixture of both, after Caesarean section. Comparison of extradural fentanyl, bupivacaine and two fentanyl-bupivacaine mixtures of pain relief after abdominal surgery. Thoracic epidural infusion for postoperative pain relief following abdominal aortic surgery: Bupivacaine, fentanyl or a mixture of both Postoperative intrathecal patient-controlled analgesia with bupivacaine, sufentanil or a mixture of both. Intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine in advanced cancer pain patients implanted at home. Long-term intrathecal morphine and bupivacaine in patients with refractory cancer pain: Results from a morphine:bupivacaine dose regimen of 0. Long-term intrathecal infusion of morphine and morphine/bupivacaine mixtures in the treatment of cancer pain: A retrospective analysis of 51 cases. Efficacy and technical complications of long-term continuous intraspinal infusions of opioid and/or bupivacaine in refractory nonmalignant pain: A comparison between the epidural and the intrathecal approach with externalized or implanted catheters and infusion pumps. Continuous infusion of opioid and bupivacaine by externalized intrathecal catheters in long-term treatment of "refractory" nonmalignant pain. Intrathecal infusional therapies for intractable pain: Patient management guidelines. Synergistic antinociceptive interactions of morphine and clonidine in rats with nerve ligation injury. An isobolographic study of epidural clonidine and fentanyl after cesarean section. Analgesic and hemodynamic effects of epidural clonidine, clonidine/ morphine, and morphine after pancreatic surgery: A double-blind study. Extradural clonidine does not potentiate analgesia produced by extradural morphine after meniscectomy. Effect of postoperative analgesia on major postoperative complications: A systematic update of the evidence. A single small dose of postoperative ketamine provides rapid and sustained improvement in morphine analgesia in the presence of morphine-resistant pain. Preoperative epidural ketamine in combination with morphine does not have a clinically relevant intra- and postoperative opioid-sparing effect. Investigation of the potentiation of the analgesic effects of fentanyl by ketamine in humans: A doubleblinded, randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study of experimental pain. Epidural ketamine for postoperative pain relief after gynecologic operations: A double-blind study and comparison with epidural morphine. Ketamine potentiates analgesic effect of morphine in postoperative epidural pain control. The long-term antinociceptive effect of intrathecal S(+)-ketamine in a patient with established morphine tolerance. Patient-controlled epidural analgesia with morphine or morphine plus ketamine for postoperative pain relief. Adding ketamine in a multimodal patientcontrolled epidural regimen reduces postoperative pain and analgesic consumption. Low doses of epidural ketamine or neostigmine, but not midazolam, improve morphine analgesia in epidural terminal cancer pain therapy. Intrathecal ketamine reduces morphine requirements in patients with terminal cancer pain. Antinociceptive effects of spinal cholinesterase inhibition and isobolographic analysis of the interaction with mu and alpha 2 receptor systems.

Purchase ditropan in united states online

Because this lesion normally does not involve the trigeminal nuclei gastritis leaky gut discount 2.5 mg ditropan with visa, the loss of pain coincident with the rostral progression of thermalgesia into the facial region in an onion-skin distribution cannot be attributed to severance of rostrocaudal projections within the trigeminal nuclei. Rather, such observations would suggest that fibers decussating within the brainstem have been interrupted. It has been estimated that the visceral afferents account for about 10% of the fibers that run in the dorsal roots. Yet these visceral afferents serve an organ surface area equivalent to about 25% of the body surface, which suggests that visceral sensitivity will be poorly localized. To understand visceral pain, one must recognize that these afferents appear to converge onto somatotopically organized dorsal horn systems, which receive cutaneous input. Gallbladder and urinary bladder stimulation serves to excite cells that have a corresponding cutaneous dermatomal field. Thus, it is not surprising that certain visceral pains are associated predominantly with certain dermatomal segments. Such segments correspond with the cutaneous innervation of that particular spinal segment. These afferents enter the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to terminate in the dorsal gray matter. At this point, convergence with somatic afferent input onto common postsynaptic neurons occurs. As noted in previous sections, both spinoreticular and spinothalamic projecting neurons showed such viscerosomatic and muscular somatic convergence as a common property. Such neurons will respond not only to noxious events, that is, cardiac ischemia or smooth muscle spasm, but also to more benign input such as distention of the bladder (see previous). Ascending Projections After the injection of horseradish peroxidase into the ventrobasal thalamus of the rat, retrogradely labeled neurons are found throughout the entire trigeminal sensory complex, with the possible exception of the nucleus oralis of the spinal nucleus. Conversely, cold block of the nucleus caudalis decreases the responses of neurons in the nucleus oralis and main sensory nucleus to peripheral stimuli. Behavioral evidence for such a facilitatory action of nucleus caudalis neurons on afferent impulse transmission in the nucleus oralis and main sensory nucleus has been obtained in the cat. Medullary Reticular Formation Given the ipsilateral spinopetal projections and the reticulothalamic projections from the medullary reticular neurons Chapter 32: Physiologic and Pharmacologic Substrates of Nociception after Tissue and Nerve Injury 719 to the intralaminar and ventrobasal nuclei of the thalamus, the medullary reticular formation has been suggested as a "relay" station for the rostrad transmission of nociceptive information. Retrogradely labeled neurons have been localized to neurons in the medullary reticular formation following the injection of horseradish peroxidase into the thalamus. Neurons of the lateral reticular nucleus,498 the nucleus gigantocellularis,574-578 the nuclei raphe magnus and pallidus,342 and the nucleus locus coeruleus579 are activated by noxious or innocuous stimuli, or both, applied to their peripheral receptive fields. These receptive fields, both ipsilateral and contralateral, are large, often including an entire limb or extending over the entire body. Many of these neurons that are responsive to somatic input are also activated by auditory and visual stimuli. Thus, stimulation of spinothalamic fibers could produce a direct drive of thalamic substrates in a manner independent of the system within the nuclei being stimulated. Within the brainstem, particularly the nucleus gigantocellularis, there is a preponderance of connections with autonomic nuclei and sensations related to gastric secretion, nausea, or tachycardia that are likely to be stimulated by activation of efferent/autonomic pathways. These syndromes might be unpleasant, and such sensations themselves might underlie the "aversive" characteristics of local stimulation. It is thus possible that the role played by these nuclei is not related to the "conscious" perception of a pain event, but rather they could serve as the mediators of the autonomic sequelae evoked by high-intensity somatic stimulation. Singleunit recording has identified nociceptive-responsive cells in the parabrachial region. These cells typically have large receptive fields that include two or more body parts, suggesting that there is significant convergence from spinal lamina I neurons on these cells. Of particular interest are the massive projections that connect the central gray matter with the subjacent tegmentum. Thus, cells that appear to be activated only by noxious tail pinch can be driven by electrical stimulation of the coccygeal nerve at intensities that evoke only a fast-conducting (A) volley. Neurons of the mesencephalic reticular formation display a high degree of convergence with bilateral receptive fields that may include the entire body. The stimulus intensity that evokes escape behavior is also the minimum intensity that produces a maximum discharge rate in that neuron. The discharge frequency of thalamic neurons has been correlated with the intensity of stimuli delivered to the nucleus gigantocellularis and the escape threshold in awake animals. Stimulation of the nucleus gigantocellularis may be used to evoke learned escape behavior in rats and cats. Additionally, such stimuli can serve as an unconditioned stimulus in pavlovian conditioning paradigms. In unanesthetized animals, the activity of nucleus gigantocellularis neurons covaries with the intensity of somatic stimulation, and stimuli applied to the nucleus gigantocellularis will drive thalamic neurons, evoke escape behavior, and support pavlovian conditioning. Lesions of the nucleus gigantocellularis have been shown to attenuate the response to otherwise aversive stimuli in the absence of any significant signs of motor impairment. Several cautionary notes should be considered in these and other studies in which the behavioral effects of stimulating and lesioning of supraspinal systems are used to examine the involvement of a given structure in a pain event. Yet the failure of lesions to elevate the pain threshold indicates that this region is not essential. It might be argued that lesions failed to affect a sufficient volume of tissue and that total destruction of this complex region would leave the animal moribund. The observation that electrical stimulation of the mesencephalic reticular formation would excite spinothalamic cells suggests that pathways either originating in, or passing through, the mesencephalon may exert an excitatory effect on the activity of spinothalamic neurons otherwise evoked by noxious peripheral stimuli. Note the midline and intralaminar projections into the limbic forebrain (anterior cingulate) and inferior insula and the ventrolateral thalamus into the somatosensory cortex. Populations of neurons in the posterior nuclear complex respond to noxious stimuli. Electrical activation of A afferents from tooth pulp, presumably noxious in nature, also evokes activity in neurons of the posterior thalamic complex. Input to these nuclei is contributed primarily by the spinothalamic tract481,504,612,613 and the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis. These reticulothalamic projections are thought to be a major source of input to the intralaminar complex. The medial regions receiving ascending input are composed of several nuclear groups, including the centromedian and parafascicular region. The centromedian and parafascicular are said to receive input from the nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis (medulla). The mediodorsal is of particular interest, as it receives input primarily from spinothalamic tract neurons originating in lamina I (high-threshold marginal cells). Populations of neurons in the medial and intralaminar nuclei respond to noxious stimuli and encode the stimulus intensity in the duration and frequency of patterned discharges. Two classes of neurons have been described: those activated with a short latency to response and those activated with a long latency. The former category of neurons is found predominantly in the basomedial portions of the parafascicular nucleus, and the latter group is localized to the dorsal centromedian and parafascicular regions. Limbic System Although these comments document those pathways that are part of the classic somatosensory projection system, it has become increasingly apparent that other regions play an important role. Regions such as the anterior cingulate, insula, and amygdala are part of the limbic forebrain; they have long been presumed to play an important role in emotionality and are activated by anxiety and stress. These systmes have been shown to play a profound role in modulating the pain response. In addition to the somatosensory cortex, other regions have also been shown to be activated. As reviewed earlier, these regions receive input from medial aspects of the thalamus (as opposed to the classic relay centers of the lateral thalamus).

Buy ditropan 5mg with visa

Long tract systems that may be relevant to the rostrad transmission include the spinoreticular gastritis y diarrea buy generic ditropan, spinomesencephalic, and spinothalamic tracts. The first two have often been referred to as the paleospinothalamic system, and the last as the neospinothalamic system by virtue of the increasing size of the diencephalic projections in phylogenetically advanced species. Note the ipsilateral projection of the ventrolateral tract into the medulla and mescenephalon. Spinoreticular Projections Spinoreticular axons terminate both ipsilaterally and contralaterally to their site of origin in the spinal cord. Significant terminal fields have also been reported in the nuclei raphe magnus and pallidus,481,483,484 making both somatic and dendritic contacts. Degeneration in this bulbar region after extensive midline myelotomies has not been observed. Retrograde transport studies have demonstrated, however, that some spinifugal axons do indeed project to both the brainstem and the thalamus. Although the receptive fields are predominantly ipsilateral excitatory, bilateral fields and fields with inhibitory components have also been observed. Uniformly shorter response latencies of these neurons in the mesencephalon have been reported for contralateral as compared with ipsilateral somatic stimulation, suggesting a largely crossed afferent input. Degenerating terminals Spinothalamic Projections the cells of origin of this tract project monosynaptically to the thalamus. Retrograde labeling studies revealed that, following unilateral injection of horseradish peroxidase into the thalamus of the monkey, about 25% of the projections from the sacral cord were ipsilateral. In the rostral mesencephalon, fibers are located ventromedially to the inferior colliculus. The spinothalamic fibers differentiate into a lateral and medial component in the posterior portions of the thalamus. The medial component passes through the internal medullary lamina to terminate in the nucleus parafascicularis and intralaminar and paralaminar nuclei. In contrast, a second population of neurons appears to project largely to the medial thalamus. Note the crossed pathway into the pons and the projections from the parabrachial to medullary, mesecephalic, and diencephalic targets. Severing the cord reduces the receptive field to that observed for spinal animals and abolishes the poststimulus discharge. Thus, somatic stimuli gaining access to supraspinal centers can readdress spinal projection neurons in what appears to be a spino (contralateral)-bulbo (crossed)-spinal (ipsilateral) feedback circuit. In primates and humans, lesions of the dorsolateral quadrant have been reported to produce a hyperalgesia. Axons of spinocervical neurons project ipsilaterally in the dorsolateral quadrant of the spinal cord to terminate in the lateral cervical nucleus. Note the collaterals, which are believed to arise from these projection into the medullary and mesecephalic core. Intersegmental Systems the ability of ventrolateral cordotomies to alter pain illustrates the important role of long tracts in the rostral transmission of nociceptive information. For reasons already stated, the existence of alternate spinal pathways appears certain. Early studies showed that alternating hemisections will abolish neither the behavioral nor the autonomic responses to strong stimuli. Kerr532,533 proposed that selective destruction of the dorsal gray matter- for example, in spinonucleolysis-might prove to be a possible method of pain management in light of the relevance of nonfunicular pathways traveling in the spinal gray matter. Subsequent work revealed that such lesions could produce significant and prolonged pain relief associated with nerve avulsions and other chronic, otherwise intractable, somatosensory pain syndromes. Alternately, the recent role of cell systems in lamina X and the likelihood of local systems traveling in the dorsal columns indicates the possibility that midline myelotomies may act not only by the severance of crossing fibers, but noxious stimuli. These high-threshold units display a slowly adapting response to noxious cutaneous mechanical and thermal stimuli. In contrast, medially projecting cells have been largely characterized as highthreshold-selective. Receptive field properties of those neurons that project to the lateral thalamus are conventional (small fields with larger surrounding regions that require more intense stimulation for activation of the neuron), and many neurons have inhibitory fields extending over broad body areas. The medial portion of the tract consists largely of collaterals of the unmyelinated or lightly myelinated primary afferent fibers that travel several segments rostrally and caudally before entering the dorsal horn gray matter. Tractotomies of the medial Lissauer tract in primates exert the opposite effect and result in shrinkage of the dermatome associated with a given spinal cord root. The dorsal intracornual tract consists of small-diameter fibers coursing longitudinally through the medial regions of the nucleus proprius. Because rhizotomies do not reduce the number of these fibers, it appears they arise from intrinsic neurons. The results of a ventrolateral cordotomy clearly indicate the importance of crossed pathways; the segmental pathways are largely ipsilaterally organized. Yet evidence suggests that some primary afferent neurons do terminate contralaterally (see previous), and interneurons do cross the midline along the longitudinal axis of the cord, as evidenced by the existence of crossed reflexes. Crossing fibers may serve to transmit the ipsilateral message to a contralateral projection. Moreover, as noted previously, afferent axons collateralize and may project many segments rostrally, where they would initiate an excitation at levels above the spinal long-tract section. The existence of segmental spinal systems might explain the recurrence of pain 3 to 12 months after ventrolateral cordotomy and, particularly, the "breakthrough" mediated by small fibers that occurs when high-intensity stimuli are applied460 (see previous). Trigeminal System the essential characteristics of afferent input through the trigeminal system are similar to those of the spinal cord. However, certain morphologic and functional considerations make it worth noting this system separately. Trigeminal Input the face, head, and buccal regions are innervated by the ophthalmic, mandibular, and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve, the cell bodies of which are located in the ganglion of the fifth nerve (gasserian). The afferents are organized somatotopically in the sensory root in a medial to lateral fashion. The mandibular nerve branch is posterolaterally positioned, the ophthalmic branch anteromedially located, and the maxillary branch situated in an intermediate position. Because visceral efferent fibers are not thought to course in the portio minor, the observation that about 20% of the axons are unmyelinated suggests a situation analogous to that studied in greater detail in the lumbar and sacral cord. Physiologic studies have supported the anatomic evidence for widespread termination of trigeminal afferents within the nuclear subdivisions. Neurons responsive to tactile stimuli (subserved by activity in large-diameter afferents) are not localized to any one nucleus. Neurons responsive to thermal or noxious stimuli have been reported in the nucleus caudalis. Thus, stimulation as far caudally as the C2 root will produce an excitatory drive of neurons receiving trigeminal input,557-560 with the likelihood that unusual pain syndromes, such as those seen in atypical facial neuralgias, might reflect the contribution of these collateral projections. The role of the nucleus caudalis in pain has been emphasized on the basis that trigeminal tractotomy at the level of the medullary obex relieves ipsilateral facial pain with preservation of touch. These neurons receive convergent input from large-diameter afferents being activated by stimulation of low-threshold rapidly conducting fibers, as well as by light touch, hair movement, and vibration. Pain intensity processing within the human brain: a bilateral, distributed mechanism. These cells then project rostrally to the somatosensory cortex, where that input is similarly mapped onto a sensory homunculus. In this system, each site on the body surface is faithfully mapped, and this map is maintained to the cortex. This system is able to provide the information necessary for mapping the "sensory-discriminative" dimension of pain. In the space available, it is not possible to deal with this except to note that a variety of lesion procedures in humans and animals have been shown to psychophysically dissociate the reported stimulus intensity from its affective component. Such disconnection syndromes are produced by prefrontal lobectomies, cingulotomies, and temporal lobe/ amygdala lesions.

Order ditropan overnight delivery

Suggestive features include systemic pyrexia in association with purulence or cellulitis at the catheter insertion site (128) gastritis diet 7 hari buy ditropan 5mg low price. Delay in decompression of an epidural hematoma or abscess increases the risk of poor recovery of function (132). The use of anticoagulants during epidural infusions needs to be identified and carefully monitored. Guidelines should be established for hospital use to ensure appropriate timing and size of dosing (132). This can provide a consistent response to abnormal or undesirable observations throughout the institution. Professional bodies in a number of countries have issued guidelines for the management of acute pain. However, the benefit or otherwise of any guidelines, whether developed by institutions or professional bodies, will depend on their relevance, effective dissemination and implementation, whether they accurately reflect current knowledge, and degree of compliance. Compliance with guidelines is known to be variable, although it may be better in larger institutions (160) and where staff with pain management expertise and formal quality assurance programs that monitor pain management are available (161). Acute Pain Services Variations in Terminology the term acute pain service is used to cover a variety of different types of service. However, they also noted that it was not possible to measure the role that other factors. However, regular scheduled input from anesthesiologists and the provision of 24-hour cover may offer additional advantages (170). As well as availability of advice about pain management problems, the anesthesiologist will have expert knowledge about the pharmacology of all analgesic agents, as well as the different delivery techniques available and their risks and benefits. The anesthesiologist will also have a good understanding of the disease processes of the patients they are seeing, and may, if called on, be able to assist with acute postoperative and other medical problems. These must always be done within a cooperative and teambased approach with the primary clinicians caring for the patient. As noted earlier, suboptimal acute pain management may, in some circumstances, result in potential harm to some patients. This information, as well as the data from many surveys published since the 1950s showing that acute pain (both postoperative and in medical wards) was often undertreated, encouraged many of the advances in both acute pain management techniques and drugs made over the last two to three decades. However, these advances have not always led to the anticipated improvements in pain relief. Factors other than just the efficacy of the many techniques and drugs now available for the treatment of acute pain play a part in determining overall patient outcome and include safety (side effects and complications), cost, and any influence on patient outcome, including morbidity and recovery. Efficacy and Outcomes Information about the efficacy of various analgesic drugs and techniques comes from a variety of sources. For example, the close interest shown by investigators could lead to greater nursing attention paid to conventional methods of pain relief, with a consequent improvement in pain relief using these techniques-the "Hawthorn effect" (177). Other findings included significantly greater patient satisfaction, but no difference in length of hospital stay or the incidence of opioid-related side effects (except for an increased incidence of pruritus in the second analysis (29). It is possible that where high nurse-to-patient ratios exist-when it may be possible to give any analgesia truly "on demand"-there is little difference between the techniques. Patient-controlled analgesia had higher incidences of nausea and sedation but was less likely to cause pruritus or urinary retention (64). The device allows delivery of up to six doses each hour, up to a maximum of 80 doses in 24 hours (191,192). It must be replaced every 24 hours, is not yet available in all countries, and is designed for in-hospital use only. Unlike fentanyl patches used for chronic pain management, no reservoir of drug is left in the skin once the device is removed (193). This concern is not unreasonable given that, in any patient, it is known that opioid administration can lead to recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction when the patient is asleep. However, complications have also been documented in patients given opioids via other routes. Respiratory arrest and the death of three patients receiving postoperative bupivacaine and fentanyl epidural infusions have also been reported (203). The usual sign of respiratory depression described was a decrease in ventilatory frequency. In another report, a patient died after being given intramuscular morphine; during the 2 hours after the injection, he was noted to be "sleeping" and then "unresponsive," and an order was given to continue monitoring of vital signs (204). Epidural Analgesia Because detailed information relating to efficacy and outcomes of epidural is given in Chapter 7, a short summary only of the beneficial effects of epidural analgesia is given in this section. Thoracic epidural analgesia has also been shown to reduce the risk of pneumonia and ventilator days in patients with fractured ribs (213) and reduce the incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction (214). The elderly patient seems less likely to suffer from opioid-related nausea and vomiting (305) or pruritus (306). The range of techniques available for opioid administration in the elderly patients is the same as for their younger counterparts. Patient-controlled analgesia can be a safe and very effective method of pain relief in elderly patients, providing they have reasonably normal cognitive function (289,307,308). Like parenteral opioids, epidural opioid requirements also decrease as patient age increases (311). Effect on Local Anesthetics the half-lives of local anesthetics such as bupivacaine (312) and ropivacaine (313) are significantly increased, and clearances significantly decreased, in older patients. Age is also a factor determining the spread of local anesthetic in the epidural space and degree of motor blockade. It has been shown that, in older patients, epidural doses of levobupivacaine (315) and ropivacaine (316) result in a higher block level, thus smaller volumes will be needed to cover the same number of dermatomes. In addition, when the same volume of local anesthetic is given, the same concentration results in more intense motor blockade (316,317). However, older patients may be more susceptible to some of the side effects of epidural analgesia, including hypotension (316,318,319). Age-related changes have also been reported with other forms of regional analgesia. For example, the duration of action of sciatic nerve (320) and brachial plexus blocks (321) may be prolonged. As noted earlier, depression may also be associated with an increased incidence of persistent postsurgical pain (12). Others have noted lower pain ratings with perceived control (341) or no change (342). The -opioid receptor gene plays a role in mediating the endogenous and exogenous effects of opioids. The effects on morphine consumption of single nucleotide polymorphism at nucleotide position 118 on the -opioid receptor gene have been studied after two different types of surgery. To reach adequate levels of analgesia after total abdominal hysterectomy, Chou et al. The same group also reported similar results in patients after total knee arthroplasty (345). A different group looked at the differences in patients undergoing colorectal surgery and were unable to find a statistically significant difference, although there was a trend toward higher morphine use in patients carrying the G118 allele, but the proportion of patients with this allele was low (291). The correlation of G118 and higher opioid requirements has also been noted in patients with cancer pain (346). Gender the effect of patient gender on reported pain scores and opioid use in the acute pain setting remains poorly understood (322). Evidence suggests that opioids may be more effective in females but that this can depend on the opioid used, with the main differences being reported with -agonist opioids (322). After knee ligament reconstruction, no difference in morphine consumption was seen (327). In comparisons of reported pain scores after surgery, it has been found that female patients report higher scores than male patients. Opioid Tolerance Tolerance has been defined as "the phenomenon whereby chronic exposure to a drug diminishes its antinociceptive or analgesic effect, or creates the need for a higher dose to maintain this effect" (349). The mechanisms underlying the development of tolerance are still not fully understood, but they appear to overlap with those mechanisms that are thought to produce and maintain persistent pain states, and include desensitization and downregulation. Psychological Factors Psychological factors may play a significant role in the pain experience, whether acute or chronic, or during the transition from acute to chronic pain (330,331). It is also worth noting that withdrawal from amphetamines can result in severe sedation, which can impact on the safety of giving adequate doses of opioid.

Buy cheap ditropan online