Purchase capoten 25mg with amex

Cobedding treatment lung cancer best buy capoten, the practice of placing concerns are addressed by good hand washing and color-coding of equipment. O ther safety concerns include proper identification for medication administration and medical emergencies and maintenance of temperature stability for all cobedded infants. The practice o cobedding spread based on anecdotal in ormation, because there is limited research to support or re ute its use. Limitations of the research on cobedding include small sample size, short follow-up periods, lack of randomization, and blinding of evaluators. In ection, sa ety, and parents continuing the practice a ter discharge are major concerns o cobedding. At follow-up, preterm infants exhibit a lower threshold for sound and a reduced responsiveness to auditory stimulation. Sources of noise include heating, ventilation, and air conditioner flow units (noise levels may decrease by 2. Choosing heated humidifiers (48 dB) rather than nebulizers (69 dB) and keeping the containers full of water, rather than low, decrease noise from respiratory equipment. Nursery design changes64 include smaller cubicles rather than one large room, soundproofing materials, lights for phones and alarm systems, and minimizing equipment noise. Placing a blanket on top of the incubator or using an incubator cover muffles the noise of equipment placement; gentle, considerate (to the infant) placement of equipment on or in the incubator muffles sound; and closing portholes and drawers gently decrease the structural noises of caregiving. This (along with a brisk startle reflex from the infant) is an opportunity to teach about the noise levels generated by such activity. Infants should be kept in incubators as long as necessary to maintain heat balance. Sound sources within an incubator include its motor, infant sounds, equipment sounds inside the incubator, equipment sounds transmitted from outside the incubator, and ambient nursing noise. Inside modern incubators, motor noise does not exceed 60 dB, but this level exceeds the more recent recommendation of 50 dB. Prolonged stays in an incubator not only expose the in ant to repeated caregiving noises but also mean there will be a dearth o kinesthetic stimulation. Both the internal noise generated by the incubator and how well the incubator attenuates external noise should be considered in incubator purchases. Softly playing a radio facilitates sleep, and the infant gradually is weaned from it. Just as high-frequency sounds arouse, lowfrequency ones, such as the heartbeat, respiratory sounds, and vacuum cleaners, quiet and facilitate sleep. Although music has been shown to soothe ull-term babies, the use o music with preterm in ants has not been as well studied. Presentation of in utero sounds and a female voice to agitated, intubated preterm infants has resulted in improved oxygen saturation and behavioral states. O utcomes included (1) lower heart rates during lullabies and music with a rhythm, (2) increased caloric intake and sucking behavior with parent-selected lullabies, and (3) decreased parental stress. Among the reasons cited against their use are that their benefits and long-term consequences have not been established, their use places a nonresponsive machine between a caring person and the preterm infant, and recordings may replace exposure of the preterm to the contingent human voice. However, because preterm infants cannot habituate to sound as well as term babies can, they may be unable to tolerate any added sound and may become exhausted by such stimuli. R ole model and teach parents to gently talk to the infant while touching and giving care. For a neonate, hearing is more important than vision or attachment and bonding to the parents. A high index of suspicion about hearing loss is warranted if caregivers do not observe normal responses to sound stimulation. Hearing screening by high-risk actors alone identif es only about 50% o newborns with signif cant hearing loss; there ore, universal newborn hearing screening is the standard o care. Early studies showed light levels in the low range, from 34 to 100 lux at night and 184 to 1000 lux during the day; more recent studies report light levels ranging from low levels of 1 to 25 foot-candles (ftc) to high levels of 235 ftc. In addition, there is abundant animal, child, and adult research documenting negative biochemical and physical effects. Because infants are continuously monitored, not all infants need to be subjected to maximal illumination at all times. R andomized controlled studies show that the circadian clock of the preterm infant is entrained by cycled light. Premature visual stimulation also may interfere with auditory neurosensory development. When these infants reach the "coming-out stage" (see Box 13-2), they may signal their readiness for visually enhancing activities. In ants receiving phototherapy are deprived o visual sensory stimuli because o their protective eye pads. These should be removed during care and eeding and interaction with parents and pro essionals. Infants prefer the human face as a visual stimulus, especially the talking face, which stimulates both visual and auditory pathways. Parents often need to be encouraged that, rather than toys, their infant prefers to watch and listen to their faces and voices. In ants who exhibit gaze aversion should not be "pursued" by the ace o the parent or proessional, because this only potentiates the time "spent away" with their gaze to protect themselves from overload. Gaze aversion, flat facial affect, and absence of a smile may cast doubt on the ability of these infants to see, because there is no eye "language" or caregiver feedback of preference, recognition, and delight. Minimizing the number o care providers is crucial or these babies so that they deal with as ew caregiver cues, styles, and ways o being handled as possible. A high-risk infant is stimulated by the smell of forgotten alcohol, skin prep, or povidone-iodine (Betadine) pads inside the incubator and the unpleasant taste or smell of oral medications. Alcohol vapors rom alcohol-based hand rubs that had not completely dried be ore touching the preterm was cited as the most common unpleasant smell to which the in ants were exposed. Enhancing the olfactory environment includes having parents hold the infant or sit close if the infant cannot yet be held. However, nutritive and nonnutritive suckling are not alike (see Chapter 18); the fact that an infant vigorously sucks on a pacifier does not mean the infant will be able to suckle nutritively, because the expressive and swallow phases have not been present in nonnutritive suckling and coordination of suck, swallow, and breathing has not been necessary. This is confusing to most parents and many professionals and should be clarified for them. Although pacifiers are soothing, these infants may learn that sucking and satiety are not related. The research basis or determining readiness or initiation o oral eedings is discussed in Chapter 18 and in Box 13-2. Cue-based or infant-driven feedings are individualized eedings initiated and * R eferences 46, 120, 143, 148, 151, 209, 213, 219, 256, 293, 294, 296, 321. Feeding difficulties at the beginning of life often lead to eating problems in infancy and later in life. Feeding difficulties are stressful to all family members, complicate parenting and strain the parent-infant bond. These researchers postulate that feeding opportunities in young infants provide them with practice and experiential opportunities to develop their oral motor skills and coordination of suck-swallow-breathe. For these infants, transition time to full nipple feeding may be lengthened because of the increased work of breathing, the precedence of breathing (at an increased rate) over feeding, and changes in heart rate variability. T techniques are onlym aversive, rather than therapeutic, hese ore on babies w touch aversion at m area; individualizing ith outh therapyis im portant ii. W per orm oral exercises, do so w care-do not hen ing ith stim aversion refexes. E nhance pleasant stim to m (irst experiences w suckling have uli outh ith lasting neurobehavioral e ects). H in ant sm or taste breast m use colostrum hum m ave ell ilk; / an ilk or oral care119 b. I low rate is otes too slow atigue and rustration are increased and m result in, ay inadequate consum ption/ grow ailure. Perioral and intraoral stim ulation- acilitates developm o ent norm sucking behaviors.

Easter Flower (Pulsatilla). Capoten.

- Are there safety concerns?

- Conditions of the male or female reproductive system, tension headache, hyperactive states, insomnia, boils, skin diseases, asthma and lung disease, earache, migraines, nerve problems, general restlessness, digestive and urinary tract problems, and other conditions.

- Dosing considerations for Pulsatilla.

- How does Pulsatilla work?

- What is Pulsatilla?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96625

Order capoten visa

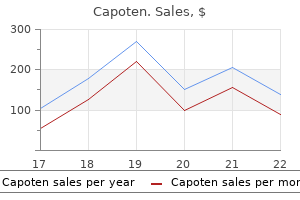

Such studies are difficult to interpret due to the many confounders (gestational age 3 medications that affect urinary elimination buy capoten master card, concurrent illness, etc. In addition, di erent instruments can vary in their measurements, and quality checks should be per ormed periodically. TcB measurements are not reliable during phototherapy because o the bleaching e ect o the light on skin. Because o the uncertain accuracy o the transcutaneous bilirubin measurement, it is not recommended to consider this device reliable at levels greater than 15 mg/ dl. A ractionated bilirubin should be obtained i the jaundice is severe, prolonged, or associated with light-colored stools. Serum albumin levels may be helpful at higher bilirubin concentrations and the bilirubin:albumin ratio considered as an additional factor in deciding when to start phototherapy or perform an exchange transfusion. Evaluation or other potential causes o hyperbilirubinemia is essential when the etiology is not immediately clear. An elevated direct fraction of bilirubin, abnormal white blood cell count, left-shifted differential, or thrombocytopenia may suggest infection. Infants suspected of having bacterial sepsis should receive antibiotic treatment and a complete sepsis evaluation performed. Infants suspected of having intrauterine infection should have additional tests, including immunoglobulin M (IgM), as well as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and/ or exudate from skin vesicles for viral cultures and urine for cytomegalovirus as indicated. In ants with hemolytic disease are at risk or late anemia a ter discharge rom the nursery, which may require treatment with erythropoietin or transfusion. These infants require close follow-up for anemia from their primary care provider. Phototherapy Phototherapy is the most commonly used treatment or hyperbilirubinemia. With the widespread use o phototherapy, the use o exchange trans usion in in ants with nonhemolytic hyperbilirubinemia is almost obsolete. Hospital-based studies in the United States have shown that 5 to 40 infants per 1000 term and late-preterm infants receive phototherapy before discharge from the nursery and an equal number are readmitted for phototherapy after discharge. T guidelines re er to the use o intensive he phototherapythat should be usedw the total serumbilirubin [T] exceeds the line indicated or each category. The rate of decline of bilirubin in the first days (early hyperbilirubinemia, likely the result of increased bilirubin production) will not be as brisk, but the rate of rise will be significantly slowed. Bilirubin best absorbs light in the blue-green spectrum, particularly in the blue region of the spectrum near 460 nm35; the spectrum of light at 425 to 475 nm is therefore most effective. Phototherapy uses this light energy to change the shape and structure o bilirubin, converting it to photoisomers that can be excreted in the bile and urine without conjugation. Lumirubin does not require conjugation and is rapidly excreted in both bile and urine. The production o lumirubin is an irreversible reaction that appears to be dose related, but occurs more slowly than formation of the configurational isomers. Photooxidation of bilirubin occurs much more slowly and is not as important as photoisomerization. The e cacy o phototherapy depends on the energy output (irradiance) o the light source (measured with a radiometer in units of watts per square centimeter or microwatts per square centimeter per nanometer over a given wavelength band), the distance o the light source rom the in ant, and the sur ace area o the in ant exposed to the light. T operational thresholds have been dem he arcated by recom endations o an expert panel. R m ecom ended threshold to prepare or exchange trans usion assum that these in ants are already es being m anaged bye ective phototherapy. Increase in exposure o body sur ace area to phototherapy m in orm the decision ay to conduct an exchange trans usion based on patient response to phototherapy. These include daylight, cool white, blue, or "special blue" fluorescent tubes or tungsten-halogen lamps in different configurations, either freestanding or as part of a radiant warming device. Most of these devices deliver enough output in the blue-green region of the visible spectrum to be effective for standard phototherapy use. The most e ective light sources commercially available or phototherapy are those that use special blue f uorescent tubes or a specially designed light-emitting diode light (Natus Inc. It is important to note that special blue tubes provide much greater irradiance than regular blue tubes (labeled F20T12/ B). Special blue tubes are most effective because they provide light predominantly in the blue-green spectrum. At these wavelengths, light penetrates skin well and is absorbed maximally by bilirubin. Purported advantages of these systems are elimination of the need for eye patches, exposure of greater surface area, and provision of phototherapy outside of the nursery with less interference in mother-infant bonding. These blankets are more convenient to use when phototherapy is necessary in an outpatient setting. Physical and laboratory evaluation should be performed before initiating phototherapy in any infant. There are conflicting data in the literature on whether continuous or intermittent administration of phototherapy is most effective. Phototherapy may be interrupted during brie periods or eeding, laboratory draws, assessment o the eyes, visual stimulation, and parental contact. Table 21-2 outlines some of the nursing assessments and management to be performed in infants undergoing phototherapy. Patches should completely cover the eyes without placing excessive pressure on the eyes and should be carefully positioned to avoid occluding the nares. Infants under phototherapy also have increased stool water losses and may develop temporary lactose intolerance. Of concern was that in a subgroup analysis o the smallest in ants, 501 to 750 grams, the mortality rate was increased by 5% in the aggressive versus conservative phototherapy group. A tight headband on eye shield to reduce risk o increased intracranial pressure, especially in void pretermin ants. An in ant with bronze baby syndrome develops a dark gray-brown discoloration o the skin, urine, and serum. There are generally no other clinical symptoms, but at least one death has been reported. Although there may be some transient, short-term growth effects, long-term growth effects and development appear unaffected by phototherapy. Phototherapy cannot be used in place o an exchange trans usion in those in ants with severe hemolytic disease. It must be stressed that the decision to per orm an exchange trans usion must be individualized or each patient. If fresh whole blood is not available, reconstituted whole blood can be requested that can be mixed to a desired hematocrit. The blood bank can prepare this blood for the infant with a predetermined hematocrit, usually 50% to 55%. An exchange trans usion will reduce bilirubin levels by approximately 45% to 85%, according to various sources. Administration of 1 g/ kg of 25% albumin 1 hour before the exchange transfusion has been shown in some studies to increase the efficiency of exchange by about 40%. As plasma and tissue levels equilibrate posttrans usion, the bilirubin rises to about 60% o the preexchange level. Exchange transfusion trays are commercially available and include a four-way stopcock, necessary tubing and syringes, 10% calcium gluconate, and a plastic bag for discarded blood. Feedings should be held or 2 to 3 hours be ore the procedure and or some time a terward. Generally, 5- to 20-ml aliquots of blood are used, depending on the size and condition of the infant. Each aliquot should be 5% to 8% of the estimated blood volume or 5 ml/ kg, withdrawn or infused at approximately 5 ml/ kg/ min. The entire procedure should take 60 to 90 minutes and encompass 30 to 35 cycles o withdrawal and in usion.

Buy cheap capoten on line

Griffin T: Visitation patterns: the parents who visit "too much medications kosher for passover purchase cheap capoten line," Neonatal N etw 17:67, 1998. Griffin T: Visitation patterns: the parents who visit "too little," Neonatal N etw 18:75, 1999. Griffin T: A family-centered "visitation" policy in the neonatal intensive care unit that welcomes parents as partners, J Perinat Neonatal N urs 27:160, 2013. Griffin T, Abraham M: Transition to home from the newborn intensive care unit: applying the principles of family-centered care to the discharge process, J Perinat N eonatal N urs 20:243, 2006. Hanna B, Jarman H, Savage S, et al: the early detection of postpartum depression: midwives and nurses trial: a checklist, J Obstet Gynecol N eonatal N urs 33:191, 2004. Harrison H: the principles for family-centered neonatal care, Pediatrics 92:643, 1993. Huhtala M, Korja R, Lehtonen L, et al: Parental psychological well-being and behavioral outcome of very low birth weight infants at 3 years, Pediatrics 129:e937, 2012. Institute for Family-Centered Care: Rationale for family-centered care, Bethesda, Md, 2002, the Institute. Jackson K, Ternestedt B, Schollin J: From alienation to familiarity: experiences of mothers and fathers of preterm infants, J Adv Nurs 43:120, 2003. James L, Brody D, Hamilton Z: R isk factors for domestic violence during pregnancy: a meta-analytic review, Violence Vict 28:359, 2013. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare O rganizations: Joint Commission standards that support the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services, 2006. Keeling J, Mason T: Postnatal disclosures of domestic violence: comparison with disclosure in the first trimester of pregnancy, J Clin N urs 20:103, 2011. Klaus M, Kennell J: Interventions in the premature nursery: impact on development, Pediatr Clin North Am 29:1263, 1982. Korja R, Mauna J, Kirjavainen J, et al: Mother-infant interaction is influenced by the amount of holding in preterm infants, Early Hum Dev 84:257, 2008. Kussano C, Maehara S: Japanese and Brazilian maternal bonding behavior towards preterm infants: a comparative study, J N eonat N urs 4:23, 1998. Lavitt M: Perinatal clients and the Internet: quality of online support and potential for harm, N atl Assoc Perinat SocWork Forum 21:8, 2001. Lawhon G: Facilitation of parenting the premature infant within the newborn intensive care unit, J Perinat N eonatal N urs 16:71, 2002. Letourneau N, Dennis C, Benzies K, et al: Postpartum depression is a family affair: addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children, Issues Ment Health N urs 33:445, 2012. Lewis C, Pantell R, Sharp L: Increasing patient knowledge, satisfaction, and involvement: randomized controlled trial of a communication intervention, Pediatrics 88:351, 1991. Lilja G, Edhborg M, Nissen E: Depressive mood in women at childbirth predicts their mood and relationship with infant and partner during the first year postpartum, Scand J Caring Sci 26:245, 2012. Lindgren K: A comparison of pregnancy health practices of women in inner-city and small urban communities, J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal N urs 32:313, 2003. London F: How to prepare families for discharge in the limited time available, Pediatr N urs 30:212, 2004. Matthey S, Barnett B, Kavanagh D, et al: Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for men and comparison of item endorsement with their partners, J Affect Disord 64:175, 2001. McGrath J: Family presence during procedures: breathing life into policy and everyday practice, Newborn Infant N urs Rev 6:243, 2006. Mehran P, Simbar M, Shams J, et al: History of perinatal loss and maternal-fetal attachment behaviors, Women Birth 26:185, 2013. Melynk B, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein N, et al: Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: program effects on the mental health/ coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers, Pediatrics 113:e597, 2004. Mew A, Holditch-Davis D, Belyea M, et al: Correlates of depressive symptoms in mothers of preterm infants, N eonatal Netw 22:51, 2003. Meyer E, Garcia-Coll C, Seifer R, et al: Psychological distress in mothers of preterm infants, J Dev Behav Pediatr 16:412, 1995. Miles M, Carlson J, Funk S: Sources of support reported by mothers and fathers of infants hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit, N eonatal N etw 15:45, 1996. Miles M, Burchinal P, Holditch-Davis D, et al: Perceptions of stress, worry, and support in black and white mothers of hospitalized, medically fragile infants, J Pediatr N urs 17:82, 2002. Milgrom J, Newnham C, Anderson P, et al: Early sensitivity training for parents of preterm infants: impact on the developing brain, Pediatric Res 67:330, 2010. Moore K, Coker K, DuBuisson A, et al: Implementing potentially better practices for improving family centered care in neonatal intensive care units: success and challenges, Pediatrics 11:e437, 2003. Moore M, Moos M: Cultural competence in the care of the childbearing families, New York, 2003, March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation. Nelson A: Transition to motherhood, J Obstet Gynecol N eonatal N urs 32:465, 2003. Neufeld M, Woodrum D, Tarczy-Hornoch P: Prenatal and postnatal counseling for parents of infants at the limits of viability, Pediatr Res 47:420A, 2000. Paul D, Epps S, Leef K, et al: Prenatal consultation with a neonatologist prior to preterm delivery, J Perinatol 21:431, 2001. Petersen M, Cohen J, Parsons V: Family-centered care: "Do we practice what we preach Pessagno R A, Hunker D: Using short-term group psychotherapy as an evidence-based intervention for first-time mothers at risk for postpartum depression, Perspect Psychiatr Care 49:202, 2013. Plaza A, Garcia-Esteve L, Torres A, et al: Childhood physical abuse as a common risk factor for depression and thyroid dysfunction in the earlier postpartum, Psychiatry Res 200:329, 2012. R ao J, Anderson L, Inui T, Frankel R: Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence, Med Care 45:340, 2007. R auh C, Beetz A, Burger P, et al: Delivery mode and the course of pre-and postpartum depression, Arch Gynecol Obstet 286:1407, 2012. R eck C, Noe D, Gerstenlauer J, Stehle E: Effects of postpartum anxiety disorders and depression on maternal self-confidence, Infant Behav Dev 35:264, 2012. R oberts K: Providing culturally sensitive care to the childbearing Islamic family, Adv N eonatal Care 2:222, 2002. R oberts K: Providing culturally sensitive care to the childbearing Islamic family. Sauls D: Effects of labor support on mothers, babies, and birth outcomes, J Obstet Gynecol N eonatal N urs 31:733, 2002. The effects of intimate partner violence before, during, and after pregnancy in nurse visited first time mothers, Matern Child Health J 17:307, 2013. Shieh C, Kravitz M: Maternal-fetal attachment in pregnant women who use illicit drugs, J Obstet Gynecol N eonatal N urs 31:156, 2003. Shneyderman Y, Kiely M: Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: victim or perpetrator Silverstein M, Feinberg E, Cabral H, et al: Problem-solving education to prevent depression among low-income mothers of preterm infants: a randomized controlled pilot trial, Arch Womens Ment Health 14:317, 2011. Singer L, Salvatore A, Guo S, et al: Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birthweight infant, J Am Med Assoc 281:799, 1999. Solheim K, Spellacy C: Sibling visitation: effects on newborn infection rates, J Obstet Gynecol N eonatal N urs 17:43, 1988. Stein T, Frankel R, Krupat E: Enhancing clinician communication skills in a large healthcare organization: a longitudinal case study, Patient Educ Couns 58:4, 2005. Sullivan J: Development of father-infant attachment in fathers of preterm infants, Neonatal Netw 18:33, 1999. Takahashi Y, Tamakoshi K, Matsushima M, Kawabe T: Comparison of salivary cortisol, heart rate, and oxygen saturation between early skin-to-skin contact with different initiation and duration times in healthy, full-term infants, Early Human Dev 87:151, 2011. Talmi A, Harmon R J: R elationships between preterm infants and their parents: disruption and development, Z ero to T hree 24:13, 2003. Thomas K, R enaud M, DePaul D: Use of the Parenting Stress Index in mothers of preterm infants, Adv N eonatal Care 4:33, 2004. Tilokskulchai F, Phatthanasiriwethin S,Vichitsukon K, et al: Attachment behaviors in mothers of premature infants: a descriptive study in Thai mothers, J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 16:69, 2002. Tronick E, R eck C: Infants of depressed mothers, Harv Rev Psychiatry 17:147, 2009.

Buy capoten 25mg lowest price

Infants receiving erythropoietin therapy need additional iron supplementation medications with acetaminophen purchase capoten line, given either enterally or parenterally. A preterm infant has limited nutritional stores and quickly develops negative protein balance without early supplementation. Some recommend even more conservative limits on osmolarity or peripheral lines (500 mO sm/ L). This level of nutritional intake prevents catabolism and, in some cases, results in moderate growth. The placement of a central line for parenteral nutrition allows a higher carbohydrate load to be used, giving more calories with less fluid. In preterm infants at risk for a patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary edema, diminishing fluid intake and improving nutritional status may be important aspects of management. Strict attention to consistency of technique during the weighing process is essential to obtain accurate, reliable measurements. Biochemical Monitoring In addition to anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters may be monitored to assess nutritional adequacy. Periodic assessment of calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels is important to detect metabolic disturbances associated with osteopenia. Usefulness of the laboratory data should be balanced with the economic costs and risks from iatrogenic blood losses for the infant (Table 16-1). When serum electrolyte levels are abnormal, urinary electrolyte levels may be useful to clarify sodium and potassium requirements. Linear growth, although less a ected, is diminished a ter long periods o poor nutrition. Fetal weight gain in utero at each week of gestation is currently used as the standard to assess adequacy of postnatal growth. Midline catheters appear to be associated with lower rates of phlebitis than short peripheral catheters and with lower rates of infection and cost than central lines. Because of the risks for thromboembolic and infection complications, these lines generally are removed as soon as possible when no longer needed. The type of line used is determined by the anticipated length of time needed and the osmolarity of the substances to be infused. Veins that may be needed for percutaneous central line placement should not be sites for routine venipuncture (see Chapter 7). Percutaneous line placement involves stabilization o the vein, maximum barrier precautions (sterile gloves, gown, large drape, masks), and antiseptic preparation o the skin with 2% chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine and alcohol product. Most kits include an insertion needle that is used to puncture and tunnel through the subcutaneous tissue before entering the vein. Once the needle is within the vein, the catheter, which has been flushed with heparinized saline solution, is passed through the needle into the vein and advanced to a premeasured distance, which is the estimated location of the superior vena cava. The distal end is tunneled subcutaneously and exited through the anterior chest wall or thigh if placed in the leg. Blood glucose determinations and screening or glucosuria should be per ormed several times each day when glucose delivery is initiated or altered. When central access is obtained, a 15% to 30% dextrose concentration may be used. The glucose load is increased if either the infusion rate or glucose concentration of the infusate is increased. A rapid decrease in the in usion rate or the glucose concentration o the in usate may result in hypoglycemia. A small portion circulates to be used by other tissues for fuel or for conversion by the liver into very-low-density lipoprotein. In general, because complications o lipids are related to delay in clearance, lipids should be in used over a 24-hour period to provide the lowest hourly rate. For each gram o protein provided above the basal amount, approximately 10 kcal o nonprotein energy is needed. The daily chloride requirement is approximately 3 mEq/ kg/ day and should be balanced with acetate to avoid alkalosis or acidosis (acetate is converted to bicarbonate). Amino acid preparations also supply anions that must be recognized to calculate a balanced anion solution. Each solution provides a mixture of essential and nonessential amino acids and may or may not contain taurine and a soluble form of tyrosine. The amino acid formulation provides a well-tolerated nitrogen source for nutritional support. The essential amino acids typically found in formulations are leucine, isoleucine, lysine, valine, histidine, phenylalanine, threonine, methionine, tryptophan, and cystine. The nonessential amino acids that are typically included are alanine, arginine, proline, glutamic acid, serine, glycine, and aspartic acid. A minimum quantity o energy substrates must be provided or e ective utilization o parenteral protein. The addition o cysteine, which lowers solution pH, may enhance calcium and phosphate solubility. The solubility o the added calcium should be calculated rom the volume at the time the calcium is added, not the nal volume. The daily recommended dose is one vial or in ants weighing more than 3 kg, 65% vial or in ants 1 to 3 kg, and 30% vial or in ants less than 1 kg. Serum zinc levels usually approximate the maternal levels at birth and decline over the first week of life. Zinc supplementation should be considered from the time parenteral nutrition is initiated. Approximately two thirds of stored copper is accumulated during the last trimester. Therefore, a preterm infant may need early supplementation but a term infant has adequate hepatic stores for at least several weeks. Because copper is excreted through the biliary system, this mineral should be removed from parenteral fluids for infants with cholestasis. Supplementing very preterm in ants with selenium is associated with reduction in sepsis. The chromium dose may be reduced or discontinued in an infant with impaired renal function. Some studies have suggested that manganese and chromium should not be provided in parenteral nutrition. Food and Drug Administration requires manufacturers to report the aluminum content of parenteral products. Even in the most knowledgeable hands, accurate calculation and ordering of parenteral nutrition for preterm or ill infants is a complex task. W will e begin with approximately 60 to 70 kcal/ kg (the birth w eight is used until w eight gain is established) and advance the intake daily to reach this level. C alcium initially should be started at 2 to 3 m q/ kg/ day but m be increased as tolerated with grow to 4 to E ay th 5 m q/ kg/ day. Protein P rovision o protein nutrition is critical to this pretermin ant or grow and th to repair dam aged tissues. C m om ercially available trace elem solution (M ent ultitrace4-N eonatal, includes zinc, copper, m anganese, and chrom). T 3 g/ kg o am acids, he ino i given as T mine, adds approximately 3 mE kg o acetate to the rophA q/ solution (1 mE acetate/ 1 g amino acids). Progression O subsequent days, the dextrose concentration and lipids w be n ould advanced slow to increase the caloric intake to requirem as tolerated. There should be quality control checks to monitor for sterility breaks in equipment, personnel, environment, and solutions. Because many additives potentially can be insoluble in combination, a mixing sequence should be established that separates the most incompatible ingredients. The label on the solution always should be checked to correctly identi y the patient, using at least two identi ers, and to veri y current ormulation order. Standardized procedures must be established to avoid infectious complications from solution contamination. Solutions on the nursing units may be returned to the pharmacy or additives be ore hanging, but no additives should be placed in the solution once it is hanging. Light shielding also appears to diminish oxidative stress and alterations o lipid metabolism, resulting in lower levels o triglyceride and better substrate delivery.

Purchase capoten canada

Guidelines for expression and collection of human breastmilk symptoms heart attack order 25mg capoten mastercard, gavage feeding of human milk, and identification of oral feeding readiness all are essential elements of lactation support and success (see Chapter 18). These recommendations are supported by some evidence that has shown that providing preterm in ants with a ormula containing higher protein and energy contents a ter discharge results in improved growth. Preterm in ants with signi cant chronic lung disease or other chronic conditions that might increase energy expenditure are likely to need increased protein and energy delivery a ter discharge to maintain adequate growth. Feeding postdischarge preterm ormulas or breastmilk with higher concentrations o calcium and phosphorus results in improved bone mineralization. Close monitoring o growth (weight, length, and head circum erence or age, indices o body proportionality) and eed intake should be per ormed at discharge and regularly a ter discharge using appropriate growth curves. Abrams B, Selvin S: Maternal weight gain pattern and birth weight, Obstet Gynecol 86:163, 1995. Amaizu N, Shulman R, Schanler R, Lau C: Maturation of oral feeding skills in preterm infants, Acta Paediatr 97:61, 2008. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn: Controversies concerning vitamin K and the newborn, Pediatrics 112:191, 2003. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on N utrition: Nutritional needs of preterm infants. In Kleinman R E, editor: Pediatric nutrition handbook, Elk GroveVillage, Ill, 2013,The Academy. Association of Breastfeeding Medicine: Clinical Protocol # 24: Allergic proctocolitis in the exclusively breastfed infant, Breastfeed Med 6:435, 2011. Bertino E, Giuliani F, Baricco M, et al: Benefits of donor milk in the feeding of preterm infants, Early Hum Dev 89:S3, 2013. Bhatia J, Greer F: Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding, Pediatrics 121:1062, 2008. Burkhardt T, Schaffer L, Zimmermann R, Kurmanavicius J: Newborn weight charts underestimate the incidence of low birthweight in preterm infants, Am J Obstet Gynecol 199:139, 2008. Cacho N, Neu J: Manipulation of the intestinal microbiome in newborn infants, Adv N utr (Bethesda) 5:114, 2014. Caicedo R A, Schanler R J, Li N, Neu J:The developing intestinal ecosystem: implications for the neonate, Pediatr Res 58:625, 2005. Canadian Paediatric Society, Nutrition Committee: Nutrient needs and feeding of premature infants, Canadian Med Assoc J 152:1765, 1995. Caple J, Armentrout D, Huseby V, et al: R andomized, controlled trial of slow versus rapid feeding volume advancement in preterm infants, Pediatrics 114:1597, 2004. Clark L, Kennedy G, Pring T, Hird M: Improving bottle feeding in preterm infants: investigating the sidelying position, Infant Behav Dev 3:154, 2007. Dunn L, Hulman S, Weiner J, Kliegman R: Beneficial effects of early hypocaloric enteral feeding on neonatal gastrointestinal function: preliminary report of a randomized trial, J Pediatr 112:622, 1988. Eritsland J: Safety considerations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, Am J Clin N utr 71:197s, 2000. Gicquel C, El-O sta A, Le Bouc Y: Epigenetic regulation and fetal programming, Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 22:1, 2008. Gitlin D, Kumate J, Morales C, et al: the turnover of amniotic fluid protein in the human conceptus, Am J Obstet Gynecol 113:632, 1972. Heiman H, Schanler R J: Enteral nutrition for premature infants: the role of human milk, Semin Fetal N eonatal Med 12:26, 2007. Kashyap S, Forsyth M, Zucker C, et al: Effects of varying protein and energy intakes on growth and metabolic response in low birth weight infants, J Pediatr 108:955, 1986. Kirchengast S, Hartmann B: Maternal prepregnancy weight status and pregnancy weight gain as major determinants for newborn weight and size, Ann Hum Biol 25:17, 1998. Krishnamurthy S, Gupta P, Debnath S, Gomber S: Slow versus rapid enteral feeding advancement in preterm newborn infants 1000-1499 g: a randomized controlled trial, Acta Paediatr 99:42, 2010. Lapillonne A: Feeding the preterm infant after discharge, World Rev N utr Diet 110:264, 2014. Liepke C, Adermann K, R aida M, et al: Human milk provides peptides highly stimulating the growth of bifidobacteria, Eur J Biochem 269:712, 2002. Maheshwai N: Are young infants treated with erythromycin at risk for developing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis Mansi Y, Abdelaziz N, Ezzeldin Z, Ibrahim R: R andomized controlled trial of a high dose of oral erythromycin for the treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants, Neonatology 100:290, 2011. Martin R, Langa S, R eviriego C, et al: Human milk is a source of lactic acid bacteria for the infant gut, J Pediatr 143:754, 2003. Narayanan I, Singh B, Harvey D: Fat loss during feeding of human milk, Arch Dis Child 59:475, 1984. Neu J: Gastrointestinal development and meeting the nutritional needs of premature infants, Am J Clin N utr 85:629S, 2007. Papachatzi E, Dimitriou G, Dimitropoulos K, Vantarakis A: Prepregnancy obesity: maternal, neonatal and childhood outcomes, J Neonatal Perinatal Med 6:203, 2013. Phillips R M, Goldstein M, Hougland K, et al: Multidisciplinary guidelines for the care of late preterm infants, J Perinatol 33:S5, 2013. Pittaluga E, Vernal P, Llanos A, et al: Benefits of supplemented preterm formulas on insulin sensitivity and body composition after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit, J Pediatr 159:926, 2011. R odriguez A, R aederstorff D, Sarda P, et al: Preterm infant formula supplementation with alpha linolenic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, Eur J Clin N utr 57:727, 2003. Schanler R J, Shulman R J, Lau C: Feeding strategies for premature infants: beneficial outcomes of feeding fortified human milk versus preterm formula, Pediatrics 103:1150, 1999. Shulman R J, Schanler R J, Lau C, et al: Early feeding, feeding tolerance, and lactase activity in preterm infants, J Pediatr 133:645, 1998. Tarnow-Mordi W, Soll R F: Probiotic supplementation in preterm infants: it is time to change practice, J Pediatr 164:959, 2014. Tudehope D, Vento M, Bhutta Z, Pachi P: Nutritional requirements and feeding recommendations for small for gestational age infants, J Pediatr 162:S81, 2013. Van Den Driessche M, Peeters K, Marien P, et al: Gastric emptying in formula-fed and breast-fed infants measured with the 13C-octanoic acid breath test, J Pediatr Gastroenterol N utr 29:46, 1999. Villar J, Cogswell M, Kestler E, et al: Effect of fat and fat-free mass deposition during pregnancy on birth weight, Am J Obstet Gynecol 167:1344, 1992. Waterland R A: Epigenetic mechanisms and gastrointestinal development, J Pediatr 149:S137, 2006. Whyte R K, Campbell D, Stanhope R, et al: Energy balance in low birth weight infants fed formula of high or low mediumchain triglyceride content, J Pediatr 108:964, 1986. Published studies from 1918 on have confirmed that problems develop when human milk is replaced with artificial formulas made from the milk of other species. Milk o other species that is ed to human in ants has been known to contribute to increased in ant mortality risk. Breastfeeding as a nonpharmacologic intervention for procedure-related neonatal pain is highly recommended9 (see Chapter 12). In preterm in ants, human milk provides both shortterm and long-term advantages (Table 18-1) in a dose-dependent relationship-the more breastmilk the preterm receives, the more bene ts received. The tremendous benefits of providing human milk for all infants, but especially the premature, outweigh any apparent difficulties. Increased rehospitalization: seven old or orm ed ula an ilk ulacom pared w 0-1 or in ants w are breast ed (both partially and com ith ho pletely). W protein in hum m is m digested, w results in m rapid gastric em hey an ilk ore hich ore ptying and less gastric residual. The goal of this chapter is to give the health care provider the skill and knowledge to support the breastfeeding dyad, especially when it involves the neonate with special needs. Colostrum contains higher ash content and higher concentrations of sodium, potassium, chloride, protein, fat-soluble vitamins, and minerals than does mature milk. Colostrum has a lower fat content, especially of lauric and myristic acids, than does mature milk. This milk is yellowish, thick, and rich in antibodies, has specific gravity between 1. Transitional milk is produced between 7 and 10 days postpartum, remains high in protein and lower in fat, and has a dramatic increase in water content compared with colostrum.

Cheap 25 mg capoten with mastercard

Transparent adhesive dressings are made rom a polyurethane lm backed with adhesive that is impermeable to water and bacteria but allows air f ow treatment mononucleosis proven 25mg capoten. Hydrocolloid dressings are used over unin ected wounds and can be le t in place or 5 to 7 days while healing takes place. Another wound treatment is amorphous hydrogel applied directly onto the wound from a tube. Surgical wounds that open or dehisce are in requent but require expert wound management. N utrition is o ten a part o the process in getting these wounds to heal, as is the prevention o in ection. This allows extravasated f uid and medications to expand over a larger sur ace and not remain in a small, constricted area, which can result in greater tissue injury. Using central venous lines, such as percutaneously inserted central venous catheters, to in use highly irritating solutions and medications is also recommended. Use of moisture, heat, or cold is not recommended, because the tissue is vulnerable at this point to further injury. This medication is an enzyme that causes a breakdown of interstitial barrier and allows the diffusion of the extravasated fluid over a larger area to prevent tissue necrosis. In addition to hyaluronidase administration, creating multiple puncture holes over the area o swelling and gently squeezing or letting the extravasated f uid leak out can acilitate the removal o the in ltrate and prevent skin sloughs. Phentolamine (R egitine) is used in this case, because it directly counteracts the action o dopamine. There has been success using a generous application o amorphous hydrogel and placing the extremity in a plastic bag, the socalled bag/ boot method. In most cases, skin gra ts can be avoided by the use o appropriate wound healing techniques. In all cases o tissue injury, open wounds should be considered a portal o entry or in ection, and topical or systemic treatment should be considered. Diaper Dermatitis A common skin disruption that occurs in neonates and infants is diaper dermatitis (diaper rash). This term encompasses a range of processes that affect the perineum, groin, thighs, buttocks, and anal area of infants who are incontinent and wear some covering to collect urine and feces. Diaper dermatitis can be caused by many different mechanisms, but the condition of the skin has a direct role in the progression of skin injury. R eview articles provide an excellent background for current evidence-based care in the prevention of and treatment for diaper dermatitis. Skin that is moist and macerated becomes more permeable and susceptible to injury because wetness increases riction. In addition, moisture-laden skin is more likely to contain microorganisms than dry skin. Another component in the process of skin injury from diaper dermatitis is the effect of an alkaline pH. Specifically, both protease and lipase in stool can injure the skin, which is made up of protein and fat components. These enzymes can quickly cause significant injury to the epidermis and are responsible for the contact irritant diaper dermatitis that is commonly seen. Strategies or preventing diaper dermatitis include maintaining a skin sur ace that is dry and has a normal (acidic) skin pH. Insufficient evidence exists to support any specific type of diaper for preventing diaper dermatitis. A ter skin injury rom diaper dermatitis has occurred, protecting injured skin to prevent reinjury is the primary goal o treatment. Topical treatment for diaper dermatitis involves ointments and creams containing a variety of ingredients. O nce skin excoriations occur, keeping skin open to air may not be e ective, because the already impaired tissue may be reinjured with ecal contact, and dryness is counterproductive to healing. It is not necessary or desirable to completely remove skin barrier products with diaper changes, because this may disrupt healing tissue. Instead, remove as much waste material as possible and reapply the barrier generously to the a ected areas with each diaper change. Another class of barrier products are semipermeable barrier films, designed to repel moisture and protect the skin rom irritants. Anti ungal preparations include Mycostatin, miconazole, clotrimazole, and ketoconazole in ointment or cream orms; ointments are pre erable to coat the skin and repel moisture. O ccasionally in ants may experience extremely severe diaper dermatitis rom intestinal malabsorption syndromes or i there is constant dribbling o stool. With malabsorption, stool not only is more frequent, but also may have a high pH because of rapid transit through the small intestine resulting in significant amounts of undigested carbohydrates and stool enzymes. W hile optimal nutritional therapy is being addressed with special diets or parenteral nutrition, skin protection rom injury should be initiated. Products that contain pectin without alcohol (such as Ilex, a nonalcohol pectin paste) may provide a sturdier barrier or these in ants than zinc oxide preparations. The skin should be thoroughly cleansed be ore a very thick application o the pectin paste. Then it is necessary to apply a greasy ointment because the pectinbased paste may adhere to the diaper. When the in ant has a stool, it is not necessary to completely remove the barrier paste; the stool can be wiped away as much as possible be ore reapplying the thick paste barrier. The skin will heal under this protective covering as long as it is protected rom reinjury. In this case, Mycostatin powder attached with alcohol-free skin protectant is the first layer; then the barrier cream is applied as described previously. Other dangers include toxicity rom topically applied substances that are readily absorbed by small in ants with a large surface area to body weight ratio, as well as immature renal and hepatic function that cannot detoxify chemicals readily. There may be an added risk for injury in patients with poor per usion to extremities and in limbs that have been secured with restricting adhesives that obstruct venous return. If the epidermis has been injured, it can easily become a portal o entry or in ection. Thus a contact irritant diaper dermatitis can progress to a fungal or staphylococcal infection. Staphylococcus aureus can cause pustule ormation at hair ollicles and is a rare complication o diaper dermatitis. Some researchers believe that Candida albicans infection is a secondary invasion to skin that has been previously injured, whereas others see this organism as a primary cause of skin disruption. Parents will need education about the normal mechanisms o cord healing, including the range of appearance in umbilical cords, because some cords can appear very moist and soggy. Prevention is the primary ocus o care, and decisions about the best way to provide basic skin care and hygiene based on current research are essential or care providers, both pro essionals and parents. C w rom skin barrier but do not clean o the skin lean aste barrier because this m disrupt skin healing. T diaper m ithin urn back aw rom the cord until it alls o; as the cord separates, a ay sm am o blood stain m be on the diaper. Agren J, Sjors G, Sedin G: Transepidermal water loss in infants born at 24 and 25 weeks of gestation, Acta Paediatr 87:1185, 1998. Als H, Lawhon G, Brown E, et al: Individualized behavioral and environmental care for the very low birth weight preterm infant at high risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: neonatal intensive care unit and developmental outcome, Pediatrics 78:1123, 1986. American Academy of Pediatrics: Red book: report of the committee on infectious disease, ed 26, Elk Grove Village, Ill, 2003, the Academy. Amjad I, Murphy T, Nylander-Housholder L, R anft A: A new approach to management of intravenous infiltration in pediatric patients: pathophysiology, classification, and treatment, J Infus Nurs 34:242, 2011. Arad I, Eyal F, Fainmesser P: Umbilical cord care: a study of bacitracin ointment vs. Baley J, Kliegman R M, Boxerbaum B, et al: Fungal colonization in the very low birth weight infant, Pediatrics 78:225, 1986. Baley J, Silverman R: Systemic candidiasis: cutaneous manifestations in low birth weight infants, Pediatrics 82:211, 1988. Beaulieu M: Hyaluronidase for extravasation management, N eonatal Netw 31:413, 2012.

Syndromes

- Permanent deformity

- Alcohol intoxication

- Pulling away from family and friends, spending more time alone

- Gagging

- Bleeding or other discharge from or around the eye

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - www.cdc.gov/cfs

- Burning in the mouth

Discount 25 mg capoten free shipping

Slocum C treatment emergent adverse event 25mg capoten overnight delivery, Arko M, DiFiore J, et al: Apnea, bradycardia and desaturation in preterm infants before and after feeding, J Perinatol 29:209, 2009. Sola A: Oxygen for the preterm newborn: one infant at a time, Pediatrics 121:1257, 2008. Soll R F: Commentary on elective high-frequency oscillatory ventilation versus conventional mechanical ventilation for acute pulmonary dysfunction in preterm infants, Neonatology 103:8, 2013. Sreenan C, Lemke R, Hudson-Mason A, et al: High-flow nasal cannulae in the management of apnea of prematurity: a comparison with conventional nasal continuous positive airway pressure, Pediatrics 107:1081, 2001. Sriram S, Wall S, Khoshnood B, et al: R acial disparity in meconium-stained amniotic fluid and meconium aspiration syndrome in the United States, 1989-2000, Obstet Gynecol 102:1262, 2003. Steinhorn R H: Pharmacotherapy of pulmonary hypertension, Pediatr Clin N orth Am 59:1129, 2012. Steinhorn R H: Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension in infancy, Early Hum Dev 89:865, 2013. Stern L:Therapy of the respiratory distress syndrome, Pediatr Clin N orth Am 19:221, 1972. Sun B: Inhaled nitric oxide and neonatal brain damage: experimental and clinical evidences, J Matern Fetal N eonatal Med 25:51, 2013. Sun H, Chang R, Kang W, et al: High-frequency oscillatory ventilation versus synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation plus pressure support in preterm infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome, Respir Care 59:159, 2014. Szymankiewicz M, Vidyasagar D, Gadzinowski J: Predictors of successful extubation or preterm low-birth-weight infants with respiratory distress syndrome, Pediatr Crit Care Med 6:44, 2005. Tan B, Zhang F, Ahang X, et al: R isk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia in the neonatal intensive care unit: a metaanalysis of observational studies, Eur J Pediatr 173:427, 2014. Tang S, Zhao J, Shen J, et al: Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure in neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Indian Pediatr 50:371, 2013. Tanriverdi S, Koroglu O A, Uygur O, et al: the effect of inhaled nitric oxide therapy on thromboelastogram in newborns with persistent pulmonary hypertension, Eur J Pediatr, May 4, 2014. Tin W, Gupta S: Optimum oxygen therapy in preterm babies, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 92:F143, 2005. Tin W, Wiswell T: Adjunctive therapies in chronic lung disease: examining the evidence, Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 13:44, 2008. Tourneux P, Cardot V, Museaux N, et al: Influence of thermal drive on central sleep apnea in the preterm neonate, Sleep 31:549, 2008. Tourneux P, R akza T, Bouissou A, et al: Pulmonary circulatory effects of norepinephrine in newborn infants with persistent pulmonary hypertension, J Pediatr 153:345, 2008. Tran S, Caughey A, Musci T: Meconium-stained amniotic fluid is associated with puerperal infections, Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:746, 2003. Tsao P, Wei S, Su Y, et al: Placenta growth factor elevation in the cord blood of premature neonates predicts poor pulmonary outcome, Pediatrics 113:1348, 2004. Tuncer O, Peker E, Demir N, et al: Spectrophotometric analysis in umbilical cords of infants with meconium aspiration syndrome, J Membr Biol 246:525, 2013. Turunen R, Nupponen I, Siitonen S, et al: O nset of mechanical ventilation is associated with rapid activation of circulating phagocytes in preterm infants, Pediatrics 117:448, 2006. Vain N, Szyld E, Prudent L, et al: Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning of meconium-stained neonates before delivery of their shoulders: multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Lancet 364:597, 2004. Velaphi S, Vidayasagar D: Intrapartum and postdelivery management of infants born to mothers with meconium-stained amniotic fluid: evidence-based recommendations, Clin Perinatol 33:29, 2006. Vergine M, Copetti R, Brusa G, Cattarossi L: Lung ultrasound accuracy in respiratory distress syndrome and transient tachypnea of the newborn, N eonatology 106:87, 2014. Wapner R J, Sorokin Y, Mele L, for the N ational Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units N etwork, et al: Long-term outcomes after repeat doses of antenatal corticosteroids, N Engl J Med 357:1190, 2007. Wardle S, Hughes A, Chen S, et al: R andomized controlled trial of oral vitamin A supplementation in preterm infants to prevent chronic lung disease, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 84:F9, 2001. Wilkinson D, Andersen C, Smith K, et al: Pharyngeal pressure with high-flow nasal cannulae in premature infants, J Perinatol 28:42, 2008. Williams A, Sunderland R: Neonatal shaken baby syndrome: an aetiological view from Down Under, Arch Dis Child Fetal N eonatal Ed 86:F29, 2002. Wilson G, Hughes G, R ennie J, et al: Evaluation of two endotracheal suction regimes in babies ventilated for respiratory distress syndrome, Early Hum Dev 25:87, 1991. Wood B: Infant ribs: generalized periosteal reaction resulting from vibrator chest physiotherapy, Radiology 162:811, 1987. Wrightson D: Suctioning smarter: answers to eight common questions about endotracheal suctioning in neonates, N eonatal Netw 18:51, 1999. Zanardo V, Freato F: Home oxygen therapy in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: assessment of parental anxiety, Early Hum Dev 65:39, 2001. Fiske E: Effective strategies to prepare infants and families for home tracheostomy care, Adv N eonatal Care 4:42, 2004. Although the incidence of these conditions has remained constant at approximately 1% of all infants born in the United States, the methods of diagnosis and treatment have undergone tremendous change over the past several decades. This chapter reviews the anatomy and physiology of the fetal and neonatal circulations, the pathophysiology of congenital heart disease, and the most current evidencebased treatments. This is the direct result of advances in pediatric and fetal cardiology, cardiac surgery, neonatology, and neonatal intensive care nursing. Incidence Each year, approximately 36,000 babies born in the United States are diagnosed with congenital heart disease. The incidence of moderate to severe structural congenital heart defects in liveborn infants is 6 to 8 per 1000 live births. Infants with cardiac lesions that were once considered fatal are now surviving into adulthood. William Osler wrote that congenital heart disease was of "limited clinical interest as in a large proportion of cases the anomaly is not compatible with life, and in others, nothing can be done to remedy the defect or even relieve the symptoms. The first successful adult heart transplant in the United States was done Embryology the heart is one of the earliest differentiating and functioning organs. In human embryos, the heart begins to beat at about 22 to 23 days o li e and begins to e ectively pump blood in the ourth week o li. During the first few weeks of life, this primitive heart tube receives blood from three different venous systems (cardinal, vitelline, and umbilical) and supplies blood to six paired aortic arches. These veins and aortic arches must each regress or mature and the primitive heart tube must undergo a complex process of looping, shifting, and septating to result in a normal heart with normal venous and arterial communications. Cardiac development is almost complete by week 6 o gestation, which may be be ore a pregnancy is even recognized. Alterations in normal cardiac embryology result in a nonviable circulation (which leads to spontaneous fetal demise) or the abnormal but viable congenital heart diseases we see postnatally. These congenital heart lesions require li esaving treatment soon a ter birth, so a diagnosis must be made prenatally or within hours a ter birth to prevent cardiovascular collapse and death. Only a small percentage of this blood will travel further in the aorta to supply the rest of the body. After oxygen has been removed by the organs of the upper body, the blood returns to the right atrium through the superior vena cava. Blood is shunted rom the pulmonary artery to the aorta through a connecting etal blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus. This blood supplies the lower portion of the fetal body before returning to the placenta through the two umbilical arteries. To develop a clear understanding of the various congenital heart defects, knowledge of the basic principles of fetal circulation must be established. Highly oxygenated blood from the mother enters the fetal circulation through the vein in the umbilical cord. From the aorta, blood is first sent to the coronary arteries and brachiocephalic vessels. Both the labor process and the first few breaths of life begin the termination of fetal circulation and the transition to newborn circulation. The rst ew breaths inf ate the lungs or the rst time and also increase the oxygen content in the neonatal blood. Finally, with the clamping of the umbilical cord, umbilical venous flow ceases and the ductus venosus begins to close, with anatomic closure taking approximately 1 to 2 weeks.

Discount capoten 25 mg line

The protein and fat components of human milk are readily digestible symptoms multiple myeloma buy capoten 25 mg line, and human milk contains large numbers of enzymes that aid in nutrient digestion and processing. Exclusive human milk eeding o in ants at high risk may reduce the risk or developing atopic disease or milk protein allergy in in ancy. Human milk also is advantageous for enhancing neurodevelopment, including vision, mental scales (particularly cognition), motor scales, behavior, and hearing. Preterm in ants breast ed at discharge have less subnormal neurodevelopment at 2 to 5 years o age. In fact, the larger the fraction of total feeding provided by just human milk without supplementation, the greater the reduction in final weight at term gestational age. Nonetheless, milk from mothers of preterm infants has more protein and sodium than milk obtained at term and occasionally provides for adequate growth in larger and healthier preterm infants who have the capacity to take in larger volumes, at times over 200 ml/ kg/ day. This is particularly important when feeding preterm infants with donor human milk. Donor human milk is a pasteurized product from accredited milk banks and used when maternal milk is insufficient or unavailable, because of the multitude of benefits associated with the use of human milk in preterm infants. Donor milk is pasteurized to prevent in ections, but this removes most o the antiin ective properties o milk. R ecommendations for developing local institutional protocols to use probiotics have been published. The nutrient content of "mature" preterm human milk is compared with fortified preterm human milk and preterm formulas in Table 17-8. Preterm ormulas contain whey:casein ratios o 60:40 and have higher protein contents than those o term ormulas (2. Preterm formulas also contain less lactose as a carbohydrate source and substitute corn syrup solids for lactose to provide approximately 42% to 44% of the calories derived from this carbohydrate (largely sucrose). Preterm formulas are available in 20 and 24 kcal/ oz preparations, with similar osmolalities and renal solute loads. Soy-derived ormulas should not be used or preterm in ants because o the poorer quality o protein, lower digestibility and bioavailability, and lower calcium and zinc accretion rates seen with these ormulas. In contrast, extensively hydrolyzed ormulas may delay or prevent atopic dermatitis in in ants at high risk and who are not breast ed. The compositions of hydrolyzed formulas (partially, extensively, and completely) are shown in Table 17-5. Use of elemental formulas generally is indicated in the infant with severe liver disease and fat malabsorption, with short bowel syndrome. Occasionally, elemental formulas are useful after a severe episode of infectious gastroenteritis with mucosal injury and resulting protein or lactose intolerance. Most recent evidence also suggests that there is no bene t in eeding tolerance, enteral intake, or growth when preterm in ants are ed a partially hydrolyzed whey preterm in ant ormula, 74 although there is some evidence for benefit in certain circumstances. Caloric delivery and nutritional support can be maintained by increasing the caloric density o eedings when eeding volumes cannot be tolerated or f uid intake must be limited. This can be done by adding human milk fortifiers to the milk or formula to achieve acceptable concentrations and intakes of these nutrients. Liquid formula concentrates, including liquid protein modular and oils, also are used to increase the caloric density of infant feedings. Caloric densities o greater than 24 kcal/ oz can be achieved with orti cation, although in ants tolerate these supplements in a highly individual ashion and should be monitored or signs o eeding intolerance. The distribution of calories should maintain a balance of protein, fat, and carbohydrate at about 10%, 45%, and 45%, respectively. Increasing caloric density of feedings also necessitates less water delivery to the infant and generally leads to an increase in formula osmolality as well. Most in ants tolerate intermittent eedings delivered slowly over 30 to 60 minutes, commonly termed slow bolus eedings. However, a summary of randomized controlled trials did not find consistent differences regarding the effectiveness of continuous versus intermittent bolus nasogastric feedings, with the exception of a small subset of patients less than 1000 g who gained weight faster and tended toward earlier discharge when fed by the continuous tube feeding method. F interm or ittent eeding: in ant eeding set w syringe, m ith edicine cup, 4-F to 8-F gavage tube. G astric tube tip placem is veri ied by auscultation or abdom ent inal radiograph or pHm easurem o gastric aspirates. T tube landm ent he ark should be checked w every caregiving procedure to determ that it ith ine is still visible and at the correct location. F tubes placed nasally, a narrowpiece o tape m ark or ay be placed along the tubing on the upper lip, w a transparent dressing ith applied over the tube on the cheek. M easure or tube placem by placing tip o eeding tube at the tip o ent nose, drawto base o ear, then to hal w betw the xiphoid process ay een and the um bilicus. M tube w indelible ink pen to indicate the distance romthe tip o ark ith the tube to the corner o the m or edge o the naris. A spirate entire stom contents to assess quantity, as w as color and ach ell appearance. A report aspirates o undigested orm i am is m lso ula ount ore than one hal o the eeding or occurs m than once or i there is a ore change in abdom assessm R inal ent. Instill hum m or orm via interm gavage eeding: an ilk ula ittent D syringe rom eeding tube and rem plunger; reattach syringe etach ove to eeding tube. T higher the syringe is held, the aster the eeding he w low (about 8 inches is ideal). Interm gavage eeding via indw ittent elling eeding tube: C aspirate and eed as above. W eeding is com heck hen plete, instill 1 to 2 m sterile w to clear tubing o residual ood and cap or close l ater o the tube by attaching syringe w plunger. C ontinuous drip eedings via indw elling eeding tube: C eeding tube placem and eeding residuals every 2 to 4 hours heck ent using stopcock, w is placed betw the eeding tube and the hich een extension tubing. P ent repare up to 4 hours o breastm or orm (or am according to institutional studies ilk ula ount o bacterial grow F syringe w predeterm eeding am th). I the in ant becom apneic, bradycardic, or cyanotic es during eeding tube placem pause to allow recovery or rem the ent, ove tube and allow in ant to rest be ore trying again. I these sym s ptom occur during the eeding, stop the eeding by low ering the syringe or stopping the pum I recovery occurs quickly, resum eeding slow p. I distress continues or recurs, stop eeding and in ormthe physician or practitioner. Some neonates require gastrostomy tube placement after certain surgical procedures or if oral feeding failure is expected to be prolonged (see Chapter 28). Extended in usion times and pump position may lead to signi cant (up to 50%) at and calcium losses when gavage eeding human milk. Positioning eccentric syringes horizontally or with the tip angled upward, minimizing the length o extension tubing, streamlining eed preparation, and shortening in usion time as medically appropriate can mitigate these losses. Oral Feeding Development of appropriate neuromuscular coordination is necessary to successfully initiate oral feedings. Use of different nipple shapes and sizes and bottles that allow for infant-driven flow may facilitate safe oral feeding. Pacing of the feeding also can assist infants as they transition through the process of learning how to orally feed (also see Chapters 13 and 18). Semidemand, cue-based, or infant-driven feedings result in an earlier attainment of full oral feedings in premature infants. An in ant who is success ul at oral eeding should exhibit an active suck, coordinated swallow with breathing, minimal f uid loss around the nipple, and completion o eeding within 15 to 30 minutes. Strategies to facilitate oral feedings also include a relaxed caregiver, a quiet environment with subdued light, and a snugly wrapped infant (see Chapter 13). A too rapid change to oral eeding can result in insu cient nutrition and potential ailure to gain weight appropriately, primarily because the in ant tires with eeding and is unable to take in a su cient amount o ood. Diligent attention is warranted, and nipple feedings often have to be limited and gavage feedings continued to prevent dehydration and undernutrition. T scales help caregivers determ i in ants are readyto hese ine nipple eed, a w to assess the qualityo the eeding, and w techniques ay hat are used to deliver that nipple eeding.

Cheap capoten 25mg online

Peter C treatment naive cheap capoten online master card, Sporodowski N, Bohnhorst B, et al: Gastroesophageal reflux and apnea of prematurity: no temporal relationship, Pediatrics 109:8, 2002. Pillekamp F, Hermann C, Keller T, et al: Factors influencing apnea and bradycardia of prematurity: implications for neurodevelopmental delay, Neonatology 91:155, 2007. Piotrowski A, Sobala W, Kawczynski P: Patient initiated, pressure- regulated, volume-controlled ventilation compared with intermittent mandatory ventilation in neonates: a prospective, randomized study, Intensive Care Med 23:975, 1997. Poets C: Gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review of its role in preterm infants, Pediatrics 113:128, 2004. Pritchard M, Flenady V, Woodgate P: Systematic review of the role of preoxygenation for tracheal suctioning in ventilated newborn infants, J Paediatr Child Health 39:163, 2003. Purohit D, Caldwell C, Levkoff A: Multiple fractures due to physiotherapy in a neonate with hyaline membrane disease, Am J Dis Child 129:1103, 1975. R ainer C, Gardetto A, Fruhwirth M, et al: Breast deformity in adolescence as a result of pneumothorax drainage during neonatal intensive care, Pediatrics 111:80, 2003. R amaekersV, Casaer P, Daniels H: Cerebral hyperperfusion following episodes of bradycardia in the preterm infant, Early Hum Dev 34:199, 1993. R amanathan R: Nasal respiratory support through the nares: its time has come, J Perinatol 30(suppl):S67, 2010. R edline R, Wilson-Costello D, Hack M: Placental and other perinatal risk factors for chronic lung disease in very low birthweight infants, Pediatr Res 52:713, 2002. R ogers E, Alderdice F, McCall E, et al: R educing nososcomial infections in neonatal intensive care, J Matern Fetal N eonatal Med 23:1039, 2010. R omejko-Wolniewicz E, Teliga-Czajkowska J, Czaajkowski K: Antenatal steroids: can we optimize the dose R ushton D: Neonatal shaken baby syndrome: historical inexactitudes, Arch Dis Child Fetal N eonatal Ed 87:F161, 2003. Salama H, Abughalwa M, Taha S, et al:Transient tachypnea of the newborn: is empiric antimicrobial therapy needed Sandri F, Ancora G, Lanzoni A, et al: Prophylactic nasal continuous positive airways pressure in newborns of 28-31 weeks, gestation: multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial, Arch Dis Child Fetal N eonatal Ed 89:F394, 2004. Sarkar S, Hussain N, Herson V: Fibrin glue for persistent pneumothorax in neonates, J Perinatol 23:82, 2003. Saugstad O D, Aune D: Optimal oxygenation of extremely low birth weight infants: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the oxygen saturation target studies, N eonatology 105:55, 2014. Schipper J, Mohammad G, van Straaten H, et al: the impact of surfactant replacement therapy on cerebral and systemic circulation and lung function, Eur J Pediatr 156:224, 1997. Schmidt B, R oberts R S, Davis P, for the Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group, et al: Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity, N Engl J Med 354:2112, 2006. Schmidt B, R oberts R S, Davis P, et al: Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity, N Engl J Med 357:1893, 2007. Schulze A, Gerhardt T, Musante G, et al: Proportional assist ventilation in low birth weight infants with acute respiratory disease: a comparison to assist/ control and conventional mechanical ventilation, J Pediatr 135:339, 1999. Schulze A, R ieger-Fackeldey E, Gerhardt T, et al: R andomized crossover comparison of proportional assist ventilation and patient- triggered ventilation in extremely low birth weight infants with evolving chronic lung disease, N eonatology 92:1, 2007. Simoes E, R osenberg A, King S, et al: R oom air challenge: prediction for successful weaning of oxygen dependent infants, J Perinatol 17:125, 1997. Deoxygenated blood returns to the heart by the inferior and superior venae cavae and enters the right atrium, right ventricle, pulmonary artery, and pulmonary circulation where oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged. Oxygenated blood then returns to the heart through the pulmonary venous system and enters the left atrium, left ventricle, and ultimately the aorta and systemic arterial system. Table 24-2 shows the most common genetic abnormalities associated with congenital heart defects. Children with chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18, and trisomy 21 often have significant congenital heart disease. For example, 1p36 deletion syndrome is a microdeletion with up to 71% of patients having a structural abnormality. Traditionally, the etiology o congenital heart de ects has been viewed as multi actorial, involving a complex interaction between genetic and environmental actors. For example, women with pregestational diabetes or women with excessive alcohol consumption are at increased risk for having an infant with a heart defect. Maternal phenylketonuria, maternal systemic lupus erythematosus, or maternal infections also increase the risk of congenital heart disease for offspring. We now recognize that use of assisted reproductive technology also results in increased risk for a heart defect in fetuses conceived by these methods. Table 24-1 lists the most common maternal and familial risk factors for cardiac malformations. Box 24-1 lists fetal risk factors associated with an * R eferences 5, 35, 42, 59, 62, 63. Because o the widespread use o antenatal ultrasound, it is increasingly common or the etus to be diagnosed with congenital heart disease. Un ortunately, less than hal o children with congenital heart disease receive a prenatal diagnosis. Better screening methods are required along with referral for detailed fetal echocardiogram for any child at increased risk of having heart disease (see Box 24-1). Extracardiac anomalies should prompt re erral or intense cardiac evaluation because there is a high incidence o heart disease in children with even one other organ abnormality. Labor and delivery complications should be carefully examined for risk factors that could affect the cardiovascular system. The timing o the murmur during the cardiac cycle is important; diastolic murmurs are almost never innocent. The intensity (loudness), quality (harsh, vibratory), location, and radiation o the murmur can all be used to help make a diagnosis. Despite the presence of many heterogeneous forms of heart disease, a limited number of signs and symptoms present in the neonate. Although cardiac murmurs in the neonatal period do not necessarily indicate heart disease, they must be care ully evaluated. Murmurs associated with semilunar valve stenosis and atrioventricular valve insufficiency tend to be noted very shortly after birth. The age o the neonate when the murmur is rst noted gives an important clue skin, nail beds, and mucous membranes) is one o the most common presenting signs o congenital heart disease in the neonate. Cyanosis occurs with congenital heart disease when deoxygenated venous blood abnormally shunts "right to left" within the heart and then enters the systemic arterial system again (without going through the lungs to pick up oxygen). Depending on the underlying skin complexion, clinically apparent cyanosis is usually not visible until there is more than 3 g/ dl of desaturated hemoglobin in the arterial system. True central cyanosis should be di erentiated rom acrocyanosis (blueness o the hands and eet only), which is a normal nding in the neonate. Cyanosis in the newborn must be di erentiated between cardiac and noncardiac causes. Primary lung disease (see Chapter 23) is a common cause of labile cyanosis due to persistent pulmonary hypertension. Clinical cyanosis can occur without hypoxemia in a neonate with methemoglobinemia and polycythemia. The hyperoxia test is bene cial in di erentiating respiratory disease rom cyanotic heart disease. The hyperoxia test is performed by obtaining arterial blood gas measurements (preferably from the right radial artery) when the infant is in room air and then after the infant has been in 100% oxygen for 5 to 10 minutes. R outine pulse oximetry is per ormed in asymptomatic newborns a ter 24 hours o li e but be ore hospital discharge (see Chapter 31). O ten the degree o cyanosis is not proportional to the degree o respiratory distress evaluated rom the physical and chest x-ray examinations. If a cardiac lesion is present that allows a xed right-to-le t shunt, increasing inspired oxygen will have little e ect on the arterial blood gases. However, if the cyanosis is caused by a di usion de ect in the lungs (pulmonary disorder), the degree o cyanosis o ten decreases with increasing inspired oxygen. R espiratory distress most o ten occurs with congenital heart disease when the lungs become too "wet. When there is too much blood in the lung circulation, fluid leaks into the lung tissues and causes pulmonary edema. Signs and symptoms of respiratory distress include tachypnea, retractions, nasal flaring, head bobbing, and abdominal breathing. A chest x-ray identifies cardiomegaly and pulmonary edema, although it cannot determine whether the pulmonary edema is due to primary lung disease or a congenital heart lesion. In the early stages, the neonate may be tachypneic and tachycardic with an increased respiratory e ort, diaphoresis, hepatomegaly, and delayed capillary re ll.

Order capoten 25 mg on line