Order bentyl 20mg fast delivery

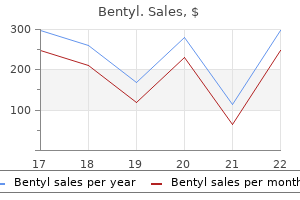

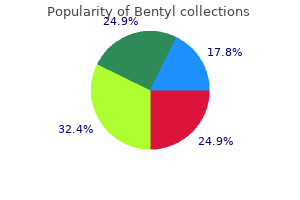

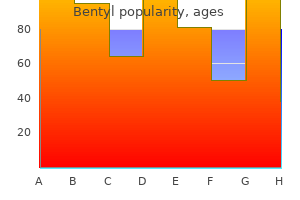

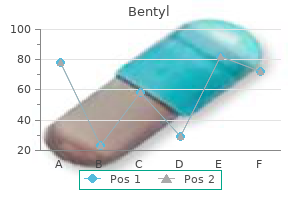

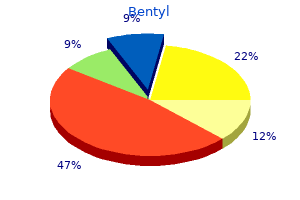

Because of this gastritis yogurt order discount bentyl on line, some women with congenital heart lesions give birth to similarly affected neonates, and the risk varies widely (Table 49-4). With complex lesions or other high-risk cases, evaluation by a multidisciplinary team is recommended early in pregnancy. Within this framework, both prognosis and management are influenced by the type and severity of the specific lesion and by the maternal functional classification. Special attention is directed toward both prevention and early recognition of heart failure. Moreover, bacterial endocarditis is a deadly complication of valvular heart disease (p. Each woman is instructed to avoid contact with persons who have respiratory infections, including the common cold, and to report at once any evidence for infection. Illicit drug use may be particularly harmful, an example being the cardiovascular effects of cocaine or amphetamines. If a woman chooses pregnancy, she must understand the risks and is encouraged to be compliant with planned care. Labor and Delivery In general, vaginal delivery is preferred, and labor induction is usually safe (Thurman, 2017). From the large Registry on Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease, Ruys and coworkers (2015) compared pregnancy outcomes between 869 women who had a planned vaginal delivery and 393 gravidas who had a planned cesarean delivery. Planned cesarean delivery conferred no advantage for maternal or neonatal outcome. Cesarean delivery is usually limited to obstetrical indications, and considerations are given for the specific cardiac lesion, overall maternal condition, and availability of experienced anesthesia personnel and hospital capabilities. Some of these women tolerate major surgical procedures poorly and are best delivered in a unit experienced with management of complicated cardiac disease. Occasionally, pulmonary artery catheterization may be needed for hemodynamic monitoring (Chap. Based on her review, Simpson (2012) recommends cesarean delivery for women with the following: (1) dilated aortic root >4 cm or aortic aneurysm; (2) acute severe congestive heart failure; (3) recent myocardial infarction; (4) severe symptomatic aortic stenosis; (5) warfarin administration within 2 weeks of delivery; and (6) need for emergency valve replacement immediately after delivery. For example, we prefer aggressive medical stabilization of pulmonary edema followed by vaginal delivery if possible. Also, warfarin anticoagulation can be reversed with vitamin K, plasma, or prothrombin concentrates. During labor, the mother with significant heart disease should be kept in a semirecumbent position with a lateral tilt. Increases in pulse rate much above 100 beats per minute (bpm) or respiratory rate above 24 per minute, particularly when associated with dyspnea, may suggest impending ventricular failure. For evidence of cardiac decompensation, intensive medical management must be instituted immediately. Delivery itself does not necessarily improve the maternal condition and, in fact, may worsen it. Clearly, both maternal and fetal status must be considered in the decision to hasten delivery under these circumstances. Although intravenous analgesics provide satisfactory pain relief for some women, continuous epidural analgesia is recommended for most. This is especially dangerous in women with intracardiac shunts in whom flow may be reversed. Hypotension can also be life-threatening if there is pulmonary arterial hypertension or aortic stenosis because ventricular output is dependent on adequate preload. In women with these conditions, narcotic regional analgesia or general anesthesia may be preferable. For vaginal delivery in women with only mild cardiovascular compromise, epidural analgesia given with intravenous sedation often suffices. This has been shown to minimize intrapartum cardiac output fluctuations and allows forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery. Subarachnoid blockade is not generally recommended in women with significant heart disease due to associated hypotension. For cesarean delivery, epidural analgesia is preferred by most clinicians with caveats for its use with pulmonary arterial hypertension (p. Intrapartum Heart Failure Cardiovascular decompensation during labor may manifest as pulmonary edema with hypoxia or as hypotension, or both. The proper therapeutic approach depends on the specific hemodynamic status and the underlying cardiac lesion. For example, decompensated mitral stenosis with pulmonary edema due to fluid overload is often best treated with aggressive diuresis. If precipitated by tachycardia, heart rate control with -blocking agents is preferred. Conversely, the same treatment in a woman suffering decompensation and hypotension due to aortic stenosis could prove fatal. Unless the underlying pathophysiology is understood and the cause of the decompensation is clear, empirical therapy may be hazardous. Puerperium Women who have shown little or no evidence of cardiac compromise during pregnancy, labor, or delivery may still decompensate postpartum. Fluid mobilized into the intravascular compartment and reduced peripheral vascular resistance place higher demands on myocardial performance. Therefore, meticulous care is continued into the puerperium (Keizer, 2006; Zeeman, 2006). Postpartum hemorrhage, anemia, infection, and thromboembolism are much more serious complications with heart disease. Indeed, these factors often act in concert to precipitate postpartum heart failure. In addition, sepsis and severe preeclampsia cause or worsen pulmonary edema because of endothelial activation and capillaryalveolar leakage (Chap. For puerperal tubal sterilization after vaginal delivery, the procedure can be delayed up to several days to ensure that the mother has normalized hemodynamically and that she is afebrile, not anemic, and ambulating normally. Alternatively, for those desiring future fertility, detailed contraceptive advice is available in the U. Examples of those frequently not diagnosed until adulthood include atrial septal defects, pulmonic stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve, and aortic coarctation (Brickner, 2014). In others, a significant anomaly is amenable to corrective surgery, performed ideally before pregnancy. Valve Replacement before Pregnancy Numerous reports describe subsequent pregnancy outcomes in women who have a prosthetic mitral or aortic valve. Using the Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease, the maternal mortality rate was 1. In total, only 58 percent with a mechanical heart valve had a pregnancy free of serious adverse events compared with 79 percent of patients with a tissue heart valve (Table 49-5). Because of thrombosis risks, anticoagulation may be requisite, but its complications are described in the next section. Thus, pregnancy is undertaken only after serious consideration for women with a prosthetic mechanical valve. Selected Outcomes in Pregnancies Complicated by Heart-Valve Replacementa Bouhout and coworkers (2014) reported the outcomes of 27 pregnancies in 14 women who underwent an aortic valve replacement prior to pregnancy. Complications in this group included two embolic myocardial infarctions and one each of miscarriage, postpartum hemorrhage, placental abruption, and preterm birth. In the bioprosthetic group, nine miscarriages, two hospitalizations for syncope, and one preterm birth were noted. Porcine tissue valves are safer during pregnancy, primarily because thrombosis is rare and anticoagulation is not required (see Table 49-5). Despite this, valvular dysfunction with cardiac deterioration poses a serious risk. Another drawback is that bioprostheses are less durable than mechanical ones, and valve replacement longevity averages 10 to 15 years. Cleuziou and colleagues (2010) concluded that pregnancy does not accelerate the risk for replacement. But, Nappi and associates (2014) found an association between pregnancy and valve deterioration in women with cryopreserved mitral homograft valves. Unfortunately, warfarin is the most effective anticoagulant for preventing maternal thromboembolism but causes harmful fetal effects (Chap. Anticoagulation with heparin is less hazardous for the fetus, however, the risk of maternal thromboembolic complications is much higher (McLintock, 2011).

Purchase cheap bentyl online

At the same time gastritis in children purchase 20mg bentyl amex, plasma volume expansion usually is normal, and thus anemia is intensified (Cunningham, 1990). Recombinant erythropoietin has been used successfully to treat anemia stemming from chronic disease (Weiss, 2005). In pregnancies complicated by chronic renal insufficiency, recombinant erythropoietin is usually considered when the hematocrit approximates 20 percent (Cyganek, 2011; Ramin, 2006). One worrisome side effect of this agent is hypertension, which is already prevalent in women with renal disease. Red cell aplasia and antierythropoietin antibodies have also been reported (Casadevall, 2002; McCoy, 2008). This leads to large cells with arrested nuclear maturation, whereas the cytoplasm matures more normally. Worldwide, the prevalence of megaloblastic anemia during pregnancy varies considerably. Folic Acid Deficiency Megaloblastic anemia developing during pregnancy almost always results from folic acid deficiency. It usually is found in women who do not consume fresh green leafy vegetables, legumes, or animal protein. As folate deficiency and anemia worsen, anorexia often becomes intense and further aggravates the dietary deficiency. Drugs and excessive ethanol ingestion either cause or contribute (Hesdorffer, 2015). The earliest biochemical evidence is low plasma folic acid concentrations (Appendix, p. Early morphological changes usually include neutrophils that are hypersegmented and newly formed erythrocytes that are macrocytic. With preexisting iron deficiency, macrocytic erythrocytes cannot be detected by measurement of the mean corpuscular volume. Careful examination of a peripheral blood smear, however, usually demonstrates some macrocytes. As the anemia becomes more intense, peripheral nucleated erythrocytes appear, and bone marrow examination discloses megaloblastic erythropoiesis. Anemia may then become severe, and thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, or both may develop. The fetus and placenta extract folate from maternal circulation so effectively that the fetus is not anemic despite severe maternal anemia. For treatment, folic acid is given along with iron, and a nutritious diet is encouraged. By 4 to 7 days after beginning folic acid treatment, the reticulocyte count is increased, and leukopenia and thrombocytopenia are corrected. For prevention of megaloblastic anemia, a diet should contain sufficient folic acid. The role of folate deficiency in the genesis of neural-tube defects has been well studied (Chap. Since the early 1990s, nutritional experts and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2016a) have recommended that all women of childbearing age consume at least 400 g of folic acid daily. More folic acid is given with multifetal pregnancy, hemolytic anemia, Crohn disease, alcoholism, and inflammatory skin disorders. Women with a family history of congenital heart disease may also benefit from higher doses (Huhta, 2015). Women who previously have had infants with neural-tube defects have a lower recurrence rate if a daily 4-mg folic acid supplement is given. Vitamin B12 Deficiency During pregnancy, vitamin B12 levels are lower than nonpregnant values because of decreased levels of binding proteins, namely, the transcobalamins. During pregnancy, megaloblastic anemia is rare from deficiency of vitamin B12, that is, cyanocobalamin. Instead, a typical example is Addisonian pernicious anemia, which results from absent intrinsic factor that is requisite for dietary vitamin B12 absorption. This autoimmune disorder usually has its onset after age 40 years (Stabler, 2013). In our limited experience, vitamin B12 deficiency in pregnancy is more likely encountered following gastric resection. Those who have undergone total gastrectomy require 1000 g of vitamin B12 given intramuscularly each month. Those with a partial gastrectomy usually do not need supplementation, but adequate serum vitamin B12 levels should be ensured (Appendix, p. Other causes of megaloblastic anemia from vitamin B12 deficiency include Crohn disease, ileal resection, some drugs, and bacterial overgrowth in the small bowel (Hesdorffer, 2015; Stabler, 2013). Damage may be stimulated by a congenital red-cell abnormality or in other cases by antibodies directed against red-cell membrane proteins. Hemolysis may be the primary disorder, and sickle-cell disease and hereditary spherocytosis are examples. In other cases, hemolysis develops secondary to an underlying condition such as systemic lupus erythematosus or preeclampsia. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia due to malignancy has been reported in pregnancy (Happe, 2016). Anemias caused by these factors may be due to warm-active autoantibodies (80 to 90 percent), cold-active antibodies, or a combination. These syndromes also may be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary due to underlying diseases or other factors. Examples of the latter include lymphomas and leukemias, connective-tissue diseases, infections, chronic inflammatory diseases, and drug-induced antibodies (Provan, 2000). Coldagglutinin disease may be induced by infectious etiologies such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Epstein-Barr viral mononucleosis (Dhingra, 2007). Hemolysis and positive antiglobulin test results may be the consequence of either immunoglobulin M (IgM) or immunoglobulin G (IgG) antierythrocyte antibodies. Transfusion of red cells is complicated by antierythrocyte antibodies, but warming the donor cells to body temperature may decrease their destruction by cold agglutinins. Drug-Induced Hemolysis these hemolytic anemias must be differentiated from other causes of autoimmune hemolysis. In most cases, hemolysis is mild, it resolves with drug withdrawal, and recurrence is prevented by avoidance of the drug. One mechanism is hemolysis induced through drug-mediated immunological injury to red cells. The drug may act as a high-affinity hapten when bound to a red-cell protein to which antidrug antibodies attach-for example, IgM antipenicillin or anticephalosporin antibodies. Some other drugs act as low-affinity haptens and adhere to cell membrane proteins. A more common mechanism for drug-induced hemolysis is related to a congenital erythrocyte enzymatic defect. An example is glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, which is common in African-American women and discussed later (p. Drug-induced hemolysis is usually chronic and mild to moderate, but occasionally acute hemolysis is severe. Garratty and coworkers (1999) described seven women with severe Coombs-positive hemolysis stimulated by cefotetan given as prophylaxis for obstetrical procedures. Moreover, maternal hemolysis has been reported after intravenous immune globulin therapy (Rink, 2013). Pregnancy-Induced Hemolysis Unexplained severe hemolytic anemia can develop during early pregnancy, and it resolves within months postpartum. A clear immune mechanism or red cell defects are not contributory (Starksen, 1983). Because the fetus-neonate also may demonstrate transient hemolysis, an immunological cause is suspected. Maternal corticosteroid treatment is often-but not always-effective (Kumar, 2001). We have cared for a woman who during each pregnancy developed intense severe hemolysis with anemia that was controlled by prednisone. Her fetuses were not affected, and in all instances, hemolysis abated spontaneously after delivery. Pregnancy-Associated Hemolysis In some cases, hemolysis is induced by conditions unique to pregnancy. Mild microangiopathic hemolysis with thrombocytopenia is relatively common with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia (Cunningham, 2015; Kenny, 2015).

Buy generic bentyl 20mg

Common bile duct exploration and drainage are used for choledocholithiasis as described in Chapter 55 (p gastritis burning stomach purchase bentyl without prescription. Several concise reviews have been provided (Cappell, 2011; Fogel, 2014; Gilinsky, 2006). For visualization of the large bowel, flexible sigmoidoscopy can be used safely in pregnant women (Siddiqui, 2006). Colonoscopy is indispensible for viewing the entire colon and distal ileum to aid diagnosis and management of several bowel disorders. Except for the midtrimester, reports of colonoscopy during pregnancy are limited, but most results indicate that it should be performed if indicated (Cappell, 2010, 2011; De Lima, 2015). Bowel preparation is completed using polyethylene glycol electrolyte or sodium phosphate solutions. With these, serious maternal dehydration that may cause diminished uteroplacental perfusion should be avoided. Noninvasive Imaging Techniques the obvious ideal technique for gastrointestinal evaluation during pregnancy is abdominal sonography. These and other imaging modalities, and their safe use in pregnancy, are considered in more detail in Chapter 46. Laparotomy and Laparoscopy Surgery is lifesaving for certain gastrointestinal conditions-perforative appendicitis being the most common example. Laparoscopic procedures have replaced traditional surgical techniques for many abdominal disorders during pregnancy. These are shown in detail with descriptions of surgical technique in Chapter 46 (p. Nutritional Support Specialized nutritional support can be delivered enterally, usually via nasogastric tube feedings, or parenterally with nutrition given by venous catheter access, either peripherally or centrally. When possible, enteral alimentation is preferable because it has fewer serious complications (Bistrian, 2012; Stokke, 2015). In obstetrical patients, very few conditions prohibit enteral nutrition as a first effort to prevent catabolism. The purpose of parenteral feeding, or hyperalimentation, is to provide nutrition when the intestinal tract must be quiescent. Central venous access is necessary for total parenteral nutrition because its hyperosmolarity requires rapid dilution in a high-flow vascular system. These solutions provide 24 to 40 kcal/kg/d, principally as a hypertonic glucose solution. Various conditions may prompt total parenteral nutrition during pregnancy (Table 54-1). Not surprisingly, gastrointestinal disorders are the most common indication, and in the many studies cited, feeding duration averaged approximately 33 days. Some Conditions Treated with Enteral or Parenteral Nutrition During Pregnancya Achalasia Anorexia nervosa Appendiceal rupture Bowel obstruction Burns Cholecystitis Crohn disease Diabetic gastropathy Esophageal injury Hyperemesis gravidarum Jejunoileal bypass Malignancies Ostomy obstruction Pancreatitis Preeclampsia syndrome Short gut syndrome Stroke Ulcerative colitis aDisorders are listed alphabetically. Data from Folk, 2004; Guglielmi, 2006; Manhadevan, 2015; Ogura, 2003; Porter, 2014; Russo-Stieglitz, 1999; Saha, 2009; Spiliopoulos, 2013. Importantly, complications of parenteral nutrition are frequent, and they may be severe (Guglielmi, 2006). An early report of 26 pregnancies described a 50-percent rate of complications, which included pneumothorax, hemothorax, and brachial plexus injury (Russo-Stieglitz, 1999). The most frequent serious complication is catheter sepsis, and Folk (2004) reported a 25-percent incidence in 27 women with hyperemesis gravidarum. Although bacterial sepsis is most common, Candida septicemia has been described (Paranyuk, 2006). Perinatal complications are uncommon, however, fetal subdural hematoma caused by maternal vitamin K deficiency has been described (Sakai, 2003). Infection is the most common serious long-term complication (Holmgren, 2008; Ogura, 2003). In a series of 84 such catheters inserted in 66 pregnant women, Cape and coworkers (2014) reported a 56-percent complication rate, of which bacteremia was the most frequent. From a review of 48 reports of nonpregnant adults, Turcotte and associates (2006) concluded that peripherally placed catheters provided no advantages compared with centrally placed ones. In a small but significant proportion of these, however, it is severe and unresponsive to simple dietary modification and antiemetics. Severe unrelenting nausea and vomiting -hyperemesis gravidarum-is defined variably as being sufficiently severe to produce weight loss, dehydration, ketosis, alkalosis from loss of hydrochloric acid, and hypokalemia. In some women, transient hepatic dysfunction develops, and biliary sludge accumulates (Matsubara, 2012). Other causes should be considered because ultimately hyperemesis gravidarum is a diagnosis of exclusion (Benson, 2013). Study criteria have not been homogeneous, thus reports of population incidences vary. There does, however, appear to be an ethnic or familial predilection (Grjibovski, 2008). In population-based studies from California, Nova Scotia, and Norway, the hospitalization rate for hyperemesis gravidarum was 0. Up to 20 percent of those hospitalized in a previous pregnancy for hyperemesis will again require hospitalization (Dodds, 2006; Trogstad, 2005). In general, obese women are less likely to be hospitalized for this (Cedergren, 2008). The etiopathogenesis of hyperemesis gravidarum is unknown and is likely multifactorial. It apparently is related to high or rapidly rising serum levels of pregnancy-related hormones. Superimposed on this hormonal cornucopia are an imposing number of biological and environmental factors. Moreover, in some but not all severe cases, interrelated psychological components play a major role (Christodoulou-Smith, 2011; McCarthy, 2011). Other factors that increase the risk for admission include hyperthyroidism, previous molar pregnancy, diabetes, gastrointestinal illnesses, some restrictive diets, and asthma and other allergic disorders (Fell, 2006; Mullin, 2012). An association of Helicobacter pylori infection has been proposed, but evidence is not conclusive (Goldberg, 2007). Chronic marijuana use may cause the similar cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (Alaniz, 2015; Andrews, 2015). And for unknown reasons-perhaps estrogen-related-a female fetus increases the risk by 1. Finally, some but not all studies have reported an association between hyperemesis gravidarum and preterm labor, placental abruption, and preeclampsia (Bolin, 2013; Vandraas, 2013; Vikanes, 2013). Complications Vomiting may be prolonged, frequent, and severe, and a list of potentially fatal complications is given in Table 54-2. Various degrees of acute kidney injury from dehydration are encountered (Nwoko, 2012). An extreme example was a woman we cared for who required 5 days of dialysis when her serum creatinine level rose to 10. Others are pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, diaphragmatic rupture, and gastroesophageal rupture-Boerhaave syndrome (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2015; Chen, 2012). Some Serious and Life-Threatening Complications of Recalcitrant Hyperemesis Gravidarum Acute kidney injury-may require dialysis Depression-cause versus effect Diaphragmatic rupture Esophageal rupture-Boerhaave syndrome Hypoprothrombinemia-vitamin K deficiency Hyperalimentation complications Mallory-Weiss tears-bleeding, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium Rhabdomyolysis Wernicke encephalopathy-thiamine deficiency At least two serious vitamin deficiencies have been reported with hyperemesis in pregnancy. In two reviews, ocular signs, confusion, and ataxia were common, but only half had this triad (Chiossi, 2006; Selitsky, 2006). At least three maternal deaths have been described, and long-term sequelae include blindness, convulsions, and coma (Selitsky, 2006). The second is vitamin K deficiency that has been reported to cause maternal coagulopathy and fetal intracranial hemorrhage, as well as vitamin K embryopathy (Kawamura, 2008; Lane, 2015; Sakai, 2003). Most women with mild to moderate symptoms respond as outpatients to any of several first-line antiemetic agents (Clark, 2014; Matthews, 2014). One that is becoming a mainstay is Diclegis-a combination of doxylamine (10 mg) plus pyridoxine (10 mg). If relief is insufficient, then additional doses, first in the morning, and then in the morning and midafternoon can be added each day to the bedtime dose. It was slightly more efficacious than a combination of doxylamine and pyridoxine in a randomized trial (Oliveira, 2014; Pasternak, 2013).

Buy bentyl visa

The manner in which chromosomes are transmitted from one generation of cells to the next and from organisms to their descendants must be exceedingly precise gastritis journal pdf cheap generic bentyl canada. In this chapter we consider exactly how genetic continuity is maintained between cells and organisms. Two major processes are involved in the genetic continuity of nucleated cells: mitosis and meiosis. Although the mechanisms of the two processes are similar in many ways, the outcomes are quite different. Mitosis leads to the production of two cells, each with the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. In contrast, meiosis reduces the genetic content and the number of chromosomes by precisely half. This reduction is essential if sexual reproduction is to occur without doubling the amount of genetic material in each new generation. Strictly speaking, mitosis is that portion of the cell cycle during which the hereditary components are equally partitioned into daughter cells. Meiosis is part of a special type of cell division that leads to the production of sex cells: gametes or spores. This process is an essential step in the transmission of genetic information from an organism to its offspring. When cells are not undergoing division, the genetic material making up chromosomes unfolds and uncoils into a diffuse network within the nucleus, generally referred to as chromatin. Before describing mitosis and meiosis, we will briefly review the structure of cells, emphasizing components that are of particular significance to genetic function. We will also compare the structural differences between the prokaryotic (nonnucleated) cells of bacteria and the eukaryotic cells of higher organisms. We then devote the remainder of the chapter to the behavior of chromosomes during cell division. Around 1940, the transmission electron microscope was in its early stages of development, and by 1950, many details of cell ultrastructure Nucleus had emerged. Under the electron microscope, cells were seen as highly varied, highly organized structures whose form and function are dependent on specific genetic expression by each cell type. A new world of whorled membranes, organelles, microtubules, granules, and filaments was revealed. Many cell components, such as the nucleolus, ribosome, and centriole, are involved directly or indirectly with genetic processes. Other components-the mitochondria and chloroplasts-contain their own unique genetic information. Here, we will focus primarily on those aspects of cell structure that relate to genetic study. All cells are surrounded by a plasma membrane, an outer covering that defines the cell boundary and delimits the cell from its immediate external environment. This membrane is not passive but instead actively controls the movement of materials into and out of the cell. In addition to this membrane, plant cells have an outer covering called the cell wall whose major component is a polysaccharide called cellulose. Consisting of glycoproteins and polysaccharides, this covering has a chemical composition that differs from comparable structures in either plants or bacteria. The glycocalyx, among other functions, provides biochemical identity at the surface of cells, and the components of the coat that establish cellular identity are under genetic control. On the surface of other cells, histocompatibility antigens, which elicit an immune response during tissue and organ transplants, are present. These molecules act as recognition sites that transfer specific chemical signals across the cell membrane into the cell. Living organisms are categorized into two major groups depending on whether or not their cells contain a nucleus. The presence of a nucleus and other membranous organelles is the defining characteristic of eukaryotic organisms. During nondivisional phases of the cell cycle, the fibers are uncoiled and dispersed into chromatin (as mentioned above). Prokaryotic organisms, of which there are two major groups, lack a nuclear envelope and membranous organelles. For the purpose of our brief discussion here, we will consider the eubacteria, the other group being the more ancient bacteria referred to as archaea. Particularly prominent are the two chromosomal areas (shown in red), called nucleoids, that have been partitioned into the daughter cells. The remainder of the eukaryotic cell within the plasma membrane, excluding the nucleus, is referred to as cytoplasm and includes a variety of extranuclear cellular organelles. In the cytoplasm, a nonparticulate, colloidal material referred to as the cytosol surrounds and encompasses the cellular organelles. The cytoplasm also includes an extensive system of tubules and filaments, comprising the cytoskeleton, which provides a lattice of support structures within the cell. Consisting primarily of microtubules, which are made of the protein tubulin, and microfilaments, which derive from the protein actin, this structural framework maintains cell shape, facilitates cell mobility, and anchors the various organelles. Mitochondria are found in most eukaryotes, including both animal and plant cells, and are the sites of the oxidative phases of cell respiration. Chloroplasts, which are found in plants, algae, and some protozoans, are associated with photosynthesis, the major energy-trapping process on Earth. They are able to duplicate themselves and transcribe and translate their own genetic information. These cytoplasmic bodies, each located in a specialized region called the centrosome, are associated with the organization of spindle fibers that function in mitosis and meiosis. In some organisms, the centriole is derived from another structure, the basal body, which is associated with the formation of cilia and flagella (hair-like and whip-like structures for propelling cells or moving materials). The organization of spindle fibers by the centrioles occurs during the early phases of mitosis and meiosis. These fibers play an important role in the movement of chromosomes as they separate during cell division. They are composed of arrays of microtubules consisting of polymers of the protein tubulin. Such an understanding will also be of critical importance in our future discussions of MendeCentromere Designation Metaphase shape Anaphase shape lian genetics. When they are examined carefully, Sister distinctive lengths and shapes are chromatids Middle Metacentric Centromere apparent. Each chromosome contains a constricted region called the Migration centromere, whose location establishes the general appearance of each chromosome. Depending Close to end Acrocentric on the position of the centromere, different arm ratios are produced. First, all somatic cells derived from members of the same species contain an identical number of chromosomes. When the lengths and centromere placements of all such chromosomes are examined, a second general feature is apparent. With the exception of sex chromosomes, they exist in pairs with regard to these two properties, and the members of each pair are called homologous chromosomes. So, for each chromosome exhibiting a specific length and centromere placement, another exists with identical features. Many bacteria and viruses have but one chromosome, and organisms such as yeasts and molds, and certain plants such as bryophytes (mosses), spend the predominant phase of their life cycle in the haploid stage. That is, they contain only one member of each homologous pair of chromosomes during most of their lives. There, the human mitotic chromosomes have been photographed, cut out of the print, and matched up, creating a display called a karyotype. As you can see, humans have a 2n number of 46 chromosomes, which on close examination exhibit a diversity of sizes and centromere placements. Note also that each of the 46 chromosomes in this karyotype is clearly a double structure consisting of two parallel sister chromatids connected by a common centromere. Had these chromosomes been allowed to continue dividing, the sister chromatids, which are replicas of one another, would have separated into the two new cells as division continued. Collectively, the genetic information contained in a haploid set of chromosomes constitutes the genome of the species.

Purchase bentyl 20 mg free shipping

It further concluded that enoxaparin and dalteparin could be given safely during pregnancy diet while having gastritis 20mg bentyl for sale. Other reports confirm their safety (Andersen, 2010; Bates, 2012; Galambosi, 2012). Nelson-Piercy and coworkers (2011) assessed the safety of tinzaparin through a comprehensive study of 1267 treated pregnant women. But, none of the neonatal deaths or congenital abnormalities was attributed to tinzaparin. The authors concluded that tinzaparin during pregnancy was safe for mother and fetus. Moreover, when given within 2 hours of cesarean delivery, these agents raise the risk of wound hematoma (van Wijk, 2002). Reversal of heparin with protamine sulfate is rarely required and is not indicated with a prophylactic dose of heparin. For women in whom anticoagulation therapy has temporarily been discontinued, pneumatic compression devices are recommended. Anticoagulation with Warfarin Compounds Vitamin K antagonists are generally contraindicated because they readily cross the placenta and may cause fetal death and malformations from hemorrhages (Chap. Postpartum venous thrombosis is usually treated with intravenous heparin and oral warfarin initiated simultaneously. Brooks and colleagues (2002) compared anticoagulation in postpartum women with that of age-matched nonpregnant controls. Newer Agents Of newer oral anticoagulants, dabigatran (Pradaxal) inhibits thrombin. Currently, very few reports address these newer agents during pregnancy, and thus the human reproductive risks are essentially unknown (Bates, 2012). Because of the potential for infant harm, a decision should be made to either avoid breastfeeding or use an alternative anticoagulant, such as warfarin, in postpartum women (Burnett, 2016). Complications of Anticoagulation Three significant complications associated with anticoagulation are hemorrhage, thrombocytopenia, and osteoporosis. The most serious complication is hemorrhage, which is more likely if there has been recent surgery or lacerations. Unfortunately, management schemes using laboratory testing to identify when a heparin dosage is sufficient to inhibit further thrombosis, yet not cause serious hemorrhage, have been discouraging. Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia There are two types-the most common is a nonimmune, benign, reversible thrombocytopenia that develops within the first few days of therapy and resolves in approximately 5 days without therapy cessation. The typical nadir is 40,000 to 80,000 platelets per microliter (Greinacher, 2015). Fausett and coworkers (2001) reported no cases among 244 heparin-treated gravidas compared with 10 among 244 nonpregnant patients. In others, they suggest monitoring every 2 or 3 days from day 4 until day 14 (Linkins, 2012). The American College of Chest Physicians recommends danaparoid (Orgaran)-a sulfated glycosaminoglycan heparinoid (Bates, 2012; Linkins, 2012). Magnani (2010) reviewed case reports of 83 pregnant women treated with danaparoid. Although it was generally effective, two patients died related to bleeding, three patients suffered nonfatal major bleeds, and three women developed thromboembolic events unresponsive to danaparoid. Other agents are fondaparinux (Arixtra)-a pentasaccharide factor Xa inhibitor and argatroban (Novastan)-a direct thrombin inhibitor (Kelton, 2013; Linkins, 2012). Heparin-Induced Osteoporosis Bone loss may develop with long-term heparin administration-usually 6 months or longer-and is more prevalent in cigarette smokers. Women treated with any heparin should be encouraged to take an oral daily 1500-mg calcium supplement (Cunningham, 2005; Lockwood, 2012). In one study, Rodger and colleagues (2007) found that long-term use of dalteparin for a mean of 212 days was not associated with a significant decline in bone mineral density. Anticoagulation and Abortion the treatment of deep-vein thrombosis with heparin does not preclude pregnancy termination by careful curettage. After the products are removed without trauma to the reproductive tract, full-dose heparin can be restarted in several hours. Anticoagulation and Delivery the effects of heparin on blood loss at delivery depend on several variables: (1) dose, route, and timing of administration; (2) number and depth of incisions and lacerations; (3) intensity of postpartum myometrial contractions; and (4) presence of other coagulation defects. Blood loss should not be greatly increased with vaginal delivery if the episiotomy is modest in depth, there are no lacerations, and the uterus promptly contracts. For example, Mueller and Lebherz (1969) described 10 women with antepartum thrombophlebitis treated with heparin. Three women who continued to receive heparin during labor and delivery bled remarkably and developed large hematomas. We wait at least 24 hours to restart therapy after cesarean delivery or after vaginal delivery with significant lacerations. Slow intravenous administration of protamine sulfate generally reverses the effect of heparin promptly and effectively. It should not be given in excess of the amount needed to neutralize the heparin, because it also has an anticoagulant effect. If it does not soon subside or if deep-vein involvement is suspected, appropriate diagnostic measures are performed. Superficial vein thrombosis raises the risk of deep-vein thrombosis four- to sixfold. Superficial thrombophlebitis is typically seen in association with varicosities or as a sequela of an indwelling intravenous catheter. According to Marik and Plante (2008), 70 percent of gravidas presenting with a pulmonary embolism have associated clinical evidence of deep-vein thrombosis. And recall that between 30 and 60 percent of women with a deep-vein thrombosis will have a coexisting silent pulmonary embolism. Clinical Presentation In almost 2500 nonpregnant patients with a proven pulmonary embolism, symptoms included dyspnea in 82 percent, chest pain in 49 percent, cough in 20 percent, syncope in 14 percent, and hemoptysis in 7 percent (Goldhaber, 1999). Other predominant clinical findings typically include tachypnea, apprehension, and tachycardia. In some cases, an accentuated pulmonic closure sound, rales, and/or friction rub is heard. Right axis deviation and T-wave inversion in the anterior chest leads may be evident on the electrocardiogram. In others, nonspecific findings may include atelectasis, an infiltrate, cardiomegaly, or an effusion (Pollack, 2011). Vascular markings in the lung region supplied by the obstructed artery can be lost. Although most women are hypoxemic, a normal arterial blood gas analysis does not exclude pulmonary embolism. Thus, the alveolar-arterial oxygen tension difference is a more useful indicator of disease. More than 86 percent of patients with acute pulmonary embolism will have an alveolar-arterial difference >20 mm Hg (Lockwood, 2012). Even with massive pulmonary embolism, signs, symptoms, and laboratory data to support the diagnosis may be deceptively nonspecific. Massive Pulmonary Embolism this is defined as embolism causing hemodynamic instability (Tapson, 2008). Acute mechanical obstruction of the pulmonary vasculature causes increased vascular resistance and pulmonary hypertension followed by acute right ventricular dilation. In otherwise healthy patients, significant pulmonary hypertension does not develop until 60 to 75 percent of the pulmonary vascular tree is occluded (Guyton, 1954). These are suspected when the pulmonary artery pressure is substantively increased as estimated by echocardiography. Note that the crosssectional area of the pulmonary trunk and the combined pulmonary arteries is 9 cm2. A large saddle embolism could occlude 50 to 90 percent of the pulmonary tree, causing hemodynamic instability. As the arteries give off distal branches, the total surface area rapidly increases, that is, 13 cm2 for the combined five lobar arteries, 36 cm2 for the combined 19 segmental arteries, and more than 800 cm2 for the total 65 subsegmental arterial branches.

Buy bentyl from india

Caution is recommended when attempting euglycemia in women with recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia chronic gastritis food allergy buy cheap bentyl. In a Cochrane database review, Middleton and colleagues (2016) determined that loose glycemic control, defined as fasting glucose values >120 mg/dL, was associated with greater risks for preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and birthweight above the 90th percentile compared with women with tight or moderate control. Importantly, no obvious benefit were gained from very tight control, defined by fasting values <90 mg/dL, and there were more cases of hypoglycemia. Thus, women with overt diabetes who have glucose values that are viewed by some as "considerably above" this 90 mg/dL threshold can expect good pregnancy outcomes. These levels may be lower in diabetic pregnancies, and interpretation is altered accordingly. Because the incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies is fivefold in mothers with diabetes, fetal echocardiography is an important part of second-trimester sonographic evaluation (Fouda, 2013). Despite advances in ultrasound technology, however, Dashe and associates (2009) cautioned that detection of fetal anomalies in obese diabetic women is more difficult than in similarly sized women without diabetes. Regarding second-trimester glucose control, euglycemia with self-monitoring continues to be the goal in management. This is followed by a greater insulin requirement due to the elevated peripheral resistance to insulin described in Chapter 4 (p. Third Trimester and Delivery During the past several decades, the threat of late-pregnancy stillbirth in women with diabetes has prompted recommendations for various fetal surveillance programs beginning in the third trimester. Such protocols include fetal movement counting, periodic fetal heart rate monitoring, intermittent biophysical profile evaluation, and contraction stress testing (Chap. None of these techniques has been subjected to prospective randomized clinical trials, and their primary value seems related to their low false-negative rates. At Parkland Hospital, women with diabetes are seen in a specialized obstetrical clinic every 2 weeks. Women are routinely instructed to perform fetal kick counts beginning early in the third trimester. While in the hospital, they continue daily fetal movement counts and undergo fetal heart rate monitoring three times a week. Labor induction may be attempted when the fetus is not excessively large and the cervix is considered favorable (Chap. Little and colleagues (2015) analyzed term singleton births from 2005 to 2011 and showed a higher percentage of diabetic women were delivered each year before 39 weeks compared with the entire cohort-37 versus 29 percent. Cesarean delivery at or near term has frequently been used to avoid traumatic birth of a large fetus in a woman with diabetes. In women with more advanced diabetes, especially those with vascular disease, the reduced likelihood of successful labor induction remote from term has also contributed to an increased cesarean delivery rate. In an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of diabetic women from University of Alabama at Birmingham according to the White classification, the rate of cesarean delivery and preeclampsia escalated with White class (Bennett, 2015). This suggests that tighter glycemic control during the third trimester might reduce late fetal compromise and cesarean delivery for fetal indications (Miailhe, 2013). The cesarean delivery rate for women with overt diabetes has remained at approximately 80 percent for the past 40 years at Parkland Hospital. Reducing or withholding the dose of long-acting insulin to be given on the day of delivery is recommended. Regular insulin should be used to meet most or all of the insulin needs of the mother during this time, because insulin requirements typically drop markedly after delivery. We have found that continuous insulin infusion by calibrated intravenous pump is most satisfactory (Table 57-10). Throughout labor and after delivery, the woman should be adequately hydrated intravenously and given glucose in sufficient amounts to maintain normoglycemia. Capillary or plasma glucose levels are checked frequently, especially during active labor, and regular insulin is administered accordingly. Insulin Management During Labor and Delivery Usual dose of intermediate-acting insulin is given at bedtime. Subsequently, insulin requirements may fluctuate markedly during the next few days. Effective contraception is especially important in women with overt diabetes to allow optimal glucose control before subsequent conception. Worldwide, its prevalence differs according to race, ethnicity, age, and body composition and by screening and diagnostic criteria. There continue to be several controversies pertaining to the diagnosis and treatment of gestational diabetes. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017a) has also updated its recommendations. These two authoritative sources provide an analysis of the issues surrounding the diagnosis and bolster the approach to identifying and treating women with gestational diabetes. The word gestational implies that diabetes is induced by pregnancy-ostensibly because of exaggerated physiological changes in glucose metabolism (Chap. Gestational diabetes is defined as carbohydrate intolerance of variable severity with onset or first recognition during pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017a). This definition applies whether or not insulin is used for treatment and undoubtedly includes some women with previously unrecognized overt diabetes. Use of the term gestational diabetes has been encouraged to communicate the need for enhanced surveillance and to stimulate women to seek further testing postpartum. The most important perinatal correlate is excessive fetal growth, which may result in both maternal and fetal birth trauma. The likelihood of fetal death with appropriately treated gestational diabetes is not different from that in the general population. Importantly, more than half of women with gestational diabetes ultimately develop overt diabetes in the ensuing 20 years. And, as discussed on page 1097, evidence is mounting for long-range complications that include obesity and diabetes in their offspring. Screening and Diagnosis Despite almost 50 years of research, there is still no agreement regarding optimal gestational diabetes screening. The difficulty in achieving consensus is underscored by the controversy following publication of the single-step approach espoused by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel (2010) and shown in Table 57-11. Threshold Values for Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes the recommended two-step approach begins with either universal or risk-based selective screening using a 50-g, 1-hour oral glucose challenge test. Participants in the Fifth International Workshop Conferences on Gestational Diabetes endorsed use of selective screening criteria shown in Table 57-12. Conversely, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017a) recommends universal screening of pregnant women using a laboratory-based blood glucose test. It is suggested that attempts to identify the 10 percent of women who should not be screened would add unnecessary complexity. For the 50-g screen, the plasma glucose level is measured 1 hour after a 50-g oral glucose load without regard to the time of day or time of last meal. In a recent review, the pooled sensitivity for a threshold of 140 mg/dL ranged from 74 to 83 percent depending on 100-g thresholds used for diagnosis (van Leeuwen, 2012). Sensitivity estimates for a 50-g screen threshold of 135 mg/dL improved only slightly to 78 to 85 percent. Importantly, specificity dropped from a range of 72 to 85 percent for 140 mg/dL to 65 to 81 percent for a threshold of 135 mg/dL. Using a threshold of 130 mg/dL marginally improves sensitivity with a further decline in specificity (Donovan, 2013). That said, in the absence of clear evidence supporting one cutoff value over another, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017a) sanctions using any one of the three 50-g screen thresholds. At Parkland Hospital, we continue to use 140 mg/dL as the screening threshold to prompt the 100-g test. Justification for screening and treatment of women with gestational diabetes was strengthened by the study by Crowther and coworkers (2005). Women were diagnosed as having gestational diabetes if their blood glucose was >100 mg/dL after an overnight fast and was between 140 and 198 mg/dL 2 hours after ingesting a 75-g glucose solution.

20 mg bentyl fast delivery

Ann Card Anaesth 13:64 gastritis diet questions discount 20mg bentyl fast delivery, 2010 Deger R, Ludmir J: Neisseria sicca endocarditis complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 72:113, 1988 Egbe A, Uppu S, Stroustrup A, et al: Incidences and sociodemographics of specific congenital heart diseases in the United States of America: an evaluation of hospital discharge diagnoses. Ann Thorac Surg 97(5):1624, 2014 Elkayam U: Clinical characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 58:659, 2011 Elkayam U: Risk of subsequent pregnancy in women with a history of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circulation 129(16):1695, 2014b Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al: Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 7(5):961, 2014 Erkut B, Kocak H, Becit N, et al: Massive pulmonary embolism complicated by a patent foramen ovale with straddling thrombus: report of a case. Contemp Ob/Gyn 44:27, 1999 Estensen M, Gude E, Ekmehag B, et al: Pregnancy in heart- and heart/lung recipients can be problematic. N Engl J Med 342:1077, 2000 Fong A, Lovell S, Gabby L, et al: Peripartum cardiomyopathy: demographics, antenatal factors, and a strong association with hypertensive disorders. J Perinatol 30:628, 2010 Gardin J, Schumacher D, Constantine G, et al: Valvular abnormalities and cardiovascular status following exposure to dexfenfluramine or phentermine/fenfluramine. Obstet Gynecol Surv 34:721, 1979 Goland S, Tsai F, Habib M, et al: Favorable outcome of pregnancy with an elective use of epoprostenol and sildenafil in women with severe pulmonary hypertension. Obstet Gynecol 118:583, 2011 Guo C, Xu D, Wang C: Successful treatment for acute aortic dissection in pregnancy-Bentall procedure concomitant with cesarean section. Annu Rev Med 63:277, 2012 Haas S, Trepte C, Rybczynski M, et al: Type A aortic dissection during late pregnancy in a patient with Marfan syndrome. Eur Heart J 36(44):3075, 2015 Haghikia A, Podewski E, Berliner D, et al: Rationale and design of a randomized, controlled multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the effect of bromocriptine on left ventricular function in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol 104(11):911, 2015 Hameed A, Akhter M, Bitar F, et al: Left atrial thrombosis in pregnant women with mitral stenosis and sinus rhythm. Obstet Gynecol 120:1013, 2012 Hassan N, Patenaude V, Oddy L, et al: Pregnancy outcomes in Marfan Syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol 94:311, 1999 Hidaka N, Chiba Y, Fukushima K, et al: Pregnant women with complete atrioventricular block: perinatal risks and review of management. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 34:1161, 2011 Hidaka N, Chiba Y, Kurita T, et al: Is intrapartum temporary pacing required for women with complete atrioventricular block Eur J Heart Fail March 27, 2017 [Epub ahead of print] Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Sliwa K: Pathophysiology and epidemiology of peripartum cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 315:1390, 1986 Jaffe R, Gruber A, Fejgin M, et al: Pregnancy with an artificial pacemaker. Circ J 76:957, 2012 Kangavari S, Collins J, Cercek B, et al: Tricuspid valve group B streptococcal endocarditis after an elective termination of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 99:83S, 2002 Kraft K, Graf M, Karch M, et al: Takotsubo syndrome after cardiopulmonary resuscitation during emergency cesarean delivery. Emphasis on congenital heart disease, Eisenmenger syndrome, postoperative deaths, and death during pregnancy and postpartum. Euro J Heart Failure 13:584, 2011 Kulas T, Habek D: Infective puerperal endocarditis caused by Escherichia coli. J Perinat Med 34:342, 2006 Kuleva M, Youssef A, Maroni E, et al: Maternal cardiac function in normal twin pregnancy: a longitudinal study. J Reprod Med 51:725, 2006 Leniak-Sobelga A, Tracz W, Kostkiewicz M, et al: Clinical and echocardiographic assessment of pregnant women with valvular heart disease-maternal and fetal outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 268:1, 2003 Li W, Li H, Long Y: Clinical characteristics and long-term predictors of persistent left ventricular systolic dysfunction in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Circ J 79(7):1609, 2015 Lupton M, Oteng-Ntim E, Ayida G, et al: Cardiac disease in pregnancy. Thromb Res 127:556, 2011 McLintock C: Thromboembolism in pregnancy: challenges and controversies in the prevention of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism and management of anticoagulation in women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. Intl J Cardiol 110:53, 2006 Melchiorre K, Sharma R, Khalil A, et al: Maternal cardiovascular function in normal pregnancy: evidence of maladaptation to chronic volume overload. Stroke 46(8):e181, 2015 Miniero R, Tardivo I, Centofanti P, et al: Pregnancy in heart transplant recipients. Genet Med 16(12):874, 2014 Nanna M, Stergiopoulos K: Pregnancy complicated by valvular heart disease: an update. J Am Heart Assoc 3:e000712, 2014 Nappi F, Spadaccio C, Chello M, et al: Impact of structural valve deterioration on outcomes in the cryopreserved mitral homograft valve. Am J Perinatol 26:153, 2009 Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, et al: A randomized study of prophylactic catheter ablation in asymptomatic patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. Tex Heart Inst J 42(2):152, 2015 Ramzy J, New G, Cheong A, et al: Iatrogenic anterior myocardial infarction secondary to ergometrine-induced coronary artery spasm during dilation and curettage for an incomplete miscarriage. N Engl J Med 375(19):1868, 2016 Reich O, Tax P, Marek J, et al: Long term results of percutaneous balloon valvoplasty of congenital aortic stenosis: independent predictors of outcome. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2005 Robins K, Lyons G: Supraventricular tachycardia in pregnancy. Heart 101(7):530, 2015 Savu O, Jurcu R, Giuc S, et al: Morphological and functional adaptation of the maternal heart during pregnancy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 5:289, 2012 Sawhney H, Aggarwal N, Suri V, et al: Maternal and perinatal outcome in rheumatic heart disease. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 80:9, 2003 Schade R, Andersohn F, Suissa S, et al: Dopamine agonists and the risk of cardiac-valve regurgitation. Cardio Rev 22(5):217, 2014 Schulte-Sasse U: Life threatening myocardial ischaemia associated with the use of prostaglandin E1 to induce abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 154:180, 1986 Seeburger J, Wilhelm-Mohr F, Falk V: Acute type A dissection at 17 weeks of gestation in a Marfan patient. Ann Thorac Surg 83:674, 2007 Seshadri S, Oakeshott P, Nelson-Piercy C, et al: Prepregnancy care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 180:122, 1999 Shroff H, Benenstein R, Freedberg R, et al: Mitral valve Libman-Sacks endocarditis visualized by real time three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. Heart 91:e3, 2005 Sliwa K, Blauwet L, Tibazarwa K, et al: Evaluation of bromocriptine in the treatment of acute severe peripartum cardiomyopathy: a proof-of-concept pilot study. Semin Perinatol 38(5):295, 2014 Stergiopoulos K, Shiang E, Bench T: Pregnancy in patients with pre-existing cardiomyopathies. Obstet Gynecol 126(2):346, 2015 Thorne S, MacGregor A, Nelson-Piercy C: Risks of contraception and pregnancy in heart disease. Heart 92(10):152, 2006 Thurman R, Zaffar N, Sayyer P, et al: Labour profile and outcomes in pregnant women with heart disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 216:S459, 2017 Trigas V, Nagdyman N, Pildner von Steinburg S, et al: Pregnancy-related obstetric and cardiologic problems in women after atrial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. Circulation 132(2):132, 2015 Vashisht A, Katakam N, Kausar S, et al: Postnatal diagnosis of maternal congenital heart disease: missed opportunities. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 56:89, 1994 Vitarelli A, Capotosto L: Role of echocardiography in the assessment and management of adult congenital heart disease in pregnancy. Circ J 79(7):1416, 2015 Watkins H, Ashrafian H, Redwood C: Inherited cardiomyopathies. Circulation 116:1736, 2007 World Health Organization: Medical eligibility for contraceptive use, 4th ed. J Clin Anesth 18:142, 2006 Yang X, Wang H, Wang Z, et al: Alteration and significance of serum cardiac troponin I and cystatin C in preeclampsia. Clin Chim Acta 374:168, 2006 Yu M, Yi K, Zhou L, et al: Pregnancy increases heart rates during paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. For the most part, autopsy will reveal the presence of renal changes usually of acute nephritis, though occasionally it may be engrafted upon a chronic process. It is now apparent that chronic hypertension is one of the most common serious complications encountered during pregnancy. The incidence of chronic hypertension complicating pregnancy varies depending on population vicissitudes. In a study of more than 56 million births from the Nationwide Patient Sample, the incidence was 1.

Purchase 20 mg bentyl otc

Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 18(2):249 gastritis symptoms heartburn discount bentyl 20mg overnight delivery, 2004 Hirsch D, Kopel V, Nadler V, et al: Pregnancy outcomes in women with primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:3401, 1998 Honegger J, Schlaffer S, Menzel C: Diagnosis of primary hypophysitis in Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(10):3841, 2015 Institute of Medicine: Dietary Reference Intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, National Academies Press, 2001 Ip P: Neonatal convulsion revealing maternal hyperparathyroidism: an unusual case of late neonatal hypoparathyroidism. New York, McGraw- Hill Education, 2015 Kamoun M, Mnif M, Charfi N, et al: Adrenal diseases during pregnancy: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management strategies. Am J Med Sci 347(1):64, 2014 Karmisholt J, Andersen S, Laurberg P: Variation in thyroid function tests in patients with stable untreated subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(11):3933, 2014 Kaur M, Pearson D, Godber I, et al: Longitudinal changes in bone mineral density during normal pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 40:795, 2011 Kraemer B, Schneider S, Rothmund R, et al: Influence of pregnancy on bone density: a risk factor for osteoporosis Obstet Gynecol 129:185, 2017 Lazarus J, Kaklamanou K: Significance of low thyroid-stimulating hormone in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 366(6):493, 2012 Lebbe M, Arlt W: What is the best diagnostic and therapeutic management strategy for an Addison patient during pregnancy Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 78(4):497, 2013 Lebbe M, Hubinot C, Bernard P, et al: Outcome of 100 pregnancies initiated under treatment with cabergoline in hyperprolactinaemic women. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 25(6):959, 2011 Lepez T, Vandewoesttyne M, Hussain S, et al: Fetal microchimeric cells in blood of women with an autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Endocrinol 55:809, 2001 Luewan S, Chakkabut P, Tongsong T: Outcomes of pregnancy complicated with hyperthyroidism: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:6093, 2005 Malekar-Raikar S, Sinnott B: Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy-a rare case of lifethreatening hypercalcemia: case report and literature review. Case Rep Endocrinol 2011:520516, 2011 Maliha G, Morgan J, Varhas M: Transient osteoporosis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 117(2 Pt 2):512, 2011 Matalon S, Sheiner E, Levy A, et al: Relationship of treated maternal hypothyroidism and perinatal outcome. New York, McGraw-Hill Education, 2015 Messuti I, Corvisieri S, Bardesono F, et al: Impact of pregnancy on prognosis of differentiated thyroid cancer: clinical and molecular features. Eur J Endocrinol 151:U25, 2004 Motivala S, Gologorsky Y, Kostandinov J, et al: Pituitary disorders during pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 40:827, 2011 Murcia M, Rebagliato M, Iniguez C, et al: Effect of iodine supplementation during pregnancy on infant neurodevelopment at 1 year of age. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 43(2): 573, 2014 Negro T, Formoso G, Mangieri T, et al: Levothyroxine treatment in euthyroid pregnant women with autoimmune thyroid disease: effects on obstetrical complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:557, 2002 Ono M, Miki N, Amano K, et al: Individualized high-dose cabergoline therapy for hyperprolactinemic infertility in women with micro- and macroprolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(6):2672, 2010 Pallan S, Rahman M, Khan A: Diagnosis and management of primary hyperparathyroidism. Postgrad Med J 74:233, 1998 Rovelli R, Vigone M, Giovanettoni C, et al: Newborns of mothers affected by autoimmune thyroiditis: the importance of thyroid function monitoring in the first months of life. J Dev Behav Pediatr 22:376, 2001 Stagnaro-Green A: Maternal thyroid disease and preterm delivery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:21, 2009 Stagnaro-Green A: Overt hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 54(3):478, 2011a Stagnaro-Green A, Glinoer D: Thyroid autoimmunity and the risk of miscarriage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 18:167, 2004 Stagnaro-Green A, Pearce E: Thyroid disorders in pregnancy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8:650, 2012a Stagnaro-Green A, Schwartz A, Gismondi R, et al: High rate of persistent hypothyroidism in a large-scale prospective study of postpartum thyroiditis in southern Italy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194:e1, 2006 Teng W, Shan Z, Teng X, et al: Effect of iodine intake on thyroid diseases in China. Am J Med Sci 340(5):402, 2010 Thangaratinam S, Tan A, Knox E, et al: Association between thyroid autoantibodies and miscarriage and preterm birth: meta-analysis of evidence. Obstet Gynecol 119(5):983, 2012 Vaidya B, Anthony S, Bilous M, et al: Detection of thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy: universal screening or targeted high-risk case finding Am J Clin Nutr 80:417, 2004 Velasco I, Carreira M, Santiago P, et al: Effect of iodine prophylaxis during pregnancy on neurocognitive development of children during the first two years of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3234, 2009 Vydt T, Verhelst J, De Keulenaer G: Cardiomyopathy and thyrotoxicosis: tachycardiomyopathy or thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy Acta Cardiol 61:115, 2006 Wallia A, Bizhanova A, Huang W, et al: Acute diabetes insipidus mediated by vasopressinase after placental abruption. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98:881, 2013 Wang W, Teng W, Shan Z, et al: the prevalence of thyroid disorders during early pregnancy in China: the benefits of universal screening in the first trimester of pregnancy. In rare instances, particularly when the pelvis is contracted in the lower portion, spontaneous rupture of the symphysis pubis or one or both sacro-iliac joints has been observed. Whitridge Williams (1903) the principal concerns in the 1st edition of Williams Obstetrics with disorders of the joints were the obstructed pelvis caused by rickets. Connective tissue disorders, which are also termed collagen vascular disorders, have two basic underlying causes. First are the immune-complex diseases in which connective tissue damage is caused by deposition of immune complexes. Because these are manifest by sterile inflammation-predominately of the skin, joints, blood vessels, and kidneys-they are referred to as rheumatic diseases. Second are the inherited disorders of bone, skin, cartilage, blood vessels, and basement membranes. Some examples include Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Pregnancy may mitigate activity in some of these syndromes as a result of the immunosuppression that also allows successful engraftment of fetal and placental tissues. One example is pregnancy-induced predominance of T2 helper cells compared with cytokine-producing T1 helper cells (Keeling, 2009). One longitudinal cohort study found that unrecognized autoimmune systemic rheumatic disorders are associated with significant risk for preeclampsia and fetal-growth restriction (Spinillo, 2016). Last, some immune-mediated diseases may either be caused or activated as a result of prior pregnancies. Fetal cell microchimerism is the persistence of fetal cells in the maternal circulation and in organs following pregnancy. These fetal cells may become engrafted in maternal tissues and stimulate autoantibodies. This raises the possibility that fetal cell microchimerism leads to the predilection for autoimmune disorders among women (Adams, 2004). Evidence for this includes fetal stem cells engrafted in tissues in women with autoimmune thyroiditis and systemic sclerosis (Jimenez, 2005; Srivatsa, 2001). Immune system abnormalities include overactive B lymphocytes that are responsible for autoantibody production. These result in tissue and cellular damage when autoantibodies or immune complexes are directed at one or more cellular nuclear components (Tsokos, 2011). In addition, immunosuppression is impaired, including regulatory T-cell function (Tower, 2013). Infection, lupus flares, end-organ failure, hypertension, stroke, and cardiovascular disease account for most deaths. Genetic influences are implicated by a higher concordance with monozygotic compared with dizygotic twins-25 versus 2 percent, respectively. Furthermore, neonatal lupus erythematosus has been reported in an infant conceived via oocyte donor to a mother with autoimmune disease with circulating anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies (Chiou, 2016). Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis Lupus is notoriously variable in its presentation, course, and outcome (Table 59- 2). Findings may be confined initially to one organ system, and others become involved later. Frequent findings are malaise, fever, arthritis, rash, pleuropericarditis, photosensitivity, anemia, and cognitive dysfunction. For example, low titers are found in normal individuals, other autoimmune diseases, acute viral infections, and chronic inflammatory processes. Lupus nephritis can also cause renal insufficiency, which is more common if there are antiphospholipid antibodies (Moroni, 2004). Elevated serum D-dimer concentrations often follow a flare or infection, but unexplained persistent elevations are associated with a high risk for thrombosis (Wu, 2008).