Buy generic xenical 60 mg on-line

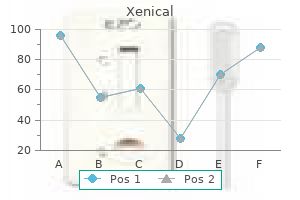

The physiology of Ca21 as a second messenger requires an analysis of two broad questions: (1) How do stimuli cause the cytosolic Ca21 concentration to increase By means of active-transport systems in the plasma membrane and membranes of certain cell organelles weight loss pills backed by science buy discount xenical on-line, Ca 21 is maintained at an extremely low concentration in the cytosol. This receptor is a ligand-gated ion channel that, when opened, allows the release of Ca21 from the endoplasmic reticulum into the cytosol. A stimulus to the cell can alter this steady state by influencing the active-transport systems and/or the ion channels, resulting in a change in cytosolic Ca 21 concentration. The most common ways that receptor activation by a first messenger increases the cytosolic Ca 21 concentration have, in part, been presented in this chapter and are summarized in the top part of Table 5. The common denominator of Ca21 actions is its ability to bind to various cytosolic proteins, altering their conformation and thereby activating their function. Calmodulin is not, however, the only intracellular protein influenced by Ca21 binding. For example, you will learn in Chapter 9 how Ca21 binds to a protein called troponin in certain types of muscle to initiate contraction. Other Messengers In a few places in this text, you will learn about messengers that are not as readily classified as those just described. On binding Ca21, the calmodulin changes shape and becomes activated, which allows it to activate or inhibit a large variety of enzymes and other proteins. Ca21 combines with Ca21-binding proteins other than calmodulin, altering their functions. They are generated in many kinds of cells in response to different types of extracellular signals; these include a variety of growth factors, immune defense molecules, and even other eicosanoids. Thus, eicosanoids may act as both extracellular and intracellular messengers, depending on the cell type. The synthesis of eicosanoids begins when an appropriate stimulus-hormone, neurotransmitter, paracrine substance, drug, or toxic agent-binds its receptor and activates phospholipase A2, an enzyme localized to the plasma membrane of the stimulated cell. The other pathway is initiated by the enzyme lipoxygenase and leads to formation of the leukotrienes. Within both of these pathways, synthesis of the various specific eicosanoids is enzymemediated. Thus, beyond phospholipase A2, the eicosanoid-pathway enzymes expressed in a particular cell determine which eicosanoids the cell synthesizes in response to a stimulus. Each of the major eicosanoid subdivisions contains more than one member, as indicated by the use of the plural in referring to them (prostaglandins, for example). Once they have been synthesized in response to a stimulus, the eicosanoids may in some cases act as intracellular messengers, but more often they are released immediately and act locally. For this reason, the eicosanoids are usually categorized as paracrine and autocrine substances. Generated from guanosine triphosphate in a reaction catalyzed by a plasma membrane receptor with guanylyl cyclase activity. Phospholipase A2 is the one enzyme common to the formation of all the eicosanoids; it is the site at which stimuli act. There are also drugs available that inhibit the lipoxygenase enzyme, thereby blocking the formation of leukotrienes. These drugs may be helpful in controlling asthma, in which excess leukotrienes have been implicated in the allergic and inflammatory components of the disease. Certain drugs influence the eicosanoid pathway and are among the most commonly used in the world today. Aspirin, for example, inhibits cyclooxygenase and, therefore, blocks the synthesis of the endoperoxides, prostaglandins, and thromboxanes. The term nonsteroidal distinguishes them from synthetic glucocorticoids (analogs of steroid hormones made by the adrenal glands) that are used in large doses as anti-inflammatory drugs; these steroids inhibit phospholipase A2 and therefore block the production of all eicosanoids. Cessation of Activity in Signal Transduction Pathways Once initiated, signal transduction pathways are eventually shut off, preventing chronic overstimulation of a cell, which can be detrimental. Responses to messengers are transient events that persist only briefly and subside when the receptor is no longer bound to the first messenger. A major way that receptor activation ceases is by a decrease in the concentration of firstmessenger molecules in the region of the receptor. This occurs as enzymes in the vicinity metabolize the first messenger, as the first messenger is taken up by adjacent cells, or as it simply diffuses away. In addition, receptors can be inactivated in at least three other ways: (1) the receptor becomes chemically altered (usually by phosphorylation), which may decrease its affinity for a first messenger, and so the messenger is released; (2) phosphorylation of the receptor may prevent further G-protein binding to the receptor; and (3) plasma membrane receptors may be removed when the combination of first messenger and receptor is taken into the cell by endocytosis. For example, in many cases the inhibitory phosphorylation of a receptor is mediated by a protein kinase that was initially activated in response to the first messenger. This concludes our description of the basic principles of signal transduction pathways. It is essential to recognize that the pathways do not exist in isolation but may be active simultaneously in a single cell, undergoing complex interactions. This is possible because a single first messenger may trigger changes in the activity of more than one pathway and, much more importantly, because many different first messengers may simultaneously influence a cell. Moreover, a great deal of "cross talk" can occur at one or more levels among the various signal transduction pathways. Receptors for chemical messengers are proteins or glycoproteins located either inside the cell or, much more commonly, in the plasma membrane. The binding of a messenger by a receptor manifests specificity, saturation, and competition. Different cell types express different types of receptors; even a single cell may express multiple receptor types. The activated receptor acts in the nucleus as a transcription factor to alter the rate of transcription of specific genes, resulting in a change in the concentration or secretion of the proteins the genes encode. The pathways induced by activation of the receptor often involve second messengers and protein kinases. The channel opens, resulting in an electrical signal in the membrane and, when Ca21 channels are involved, an increase in the cytosolic Ca21 concentration. With one exception, the enzyme activity is that of a protein kinase, usually a tyrosine kinase. The receptor may interact with an associated plasma membrane G protein, which in turn interacts with plasma membrane effector proteins-ion channels or enzymes. An activated receptor can increase cytosolic Ca21 concentration by causing certain Ca21 channels in the plasma membrane and/or endoplasmic reticulum to open. Calcium-activated calmodulin activates or inhibits many proteins, including calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. The signal transduction pathways triggered by activated plasma membrane receptors may influence genetic expression by activating transcription factors. Eicosanoids are derived from arachidonic acid, which is released from phospholipids in the plasma membrane. Cessation of receptor activity occurs when the first-messenger molecule concentration decreases or when the receptor is chemically altered or internalized, in the case of plasma membrane receptors. Describe the basis of down-regulation and up-regulation, and how these processes are related to homeostasis. Classify plasma membrane receptors according to the signal transduction pathways they initiate. Contrast receptors that have intrinsic enzyme activity with those associated with cytoplasmic janus kinases. Explain why different types of cells may respond differently to the same chemical messenger. How might this be related to the thyroid hormone imbalance that was responsible for the weight gain A 3-year-old girl was seen by her pediatrician to determine the cause of a recent increase in the rate of her weight gain. She was also prone to muscle cramps and complained to her mother that her fingers and toes "felt funny," which the pediatrician was able to interpret as tingling sensations.

Cheap xenical online mastercard

These ciliary motions sweep the egg into the fallopian tube as it emerges onto the ovarian surface weight loss motivation generic xenical 120 mg online. Within the fallopian tube, egg movement, driven almost entirely by fallopian-tube cilia, is so slow that the egg takes about 4 days to reach the uterus. If fertilization is to occur, it does so in the fallopian tube because of the short viability of the unfertilized egg. Intercourse, Sperm Transport, and Capacitation Ejaculation, described earlier in this chapter, results in deposition of semen into the vagina during intercourse. The act of intercourse itself provides some impetus for the transport of sperm out of the vagina to the cervix because of the fluid pressure of the ejaculate. Passage into the cervical mucus by the swimming sperm is dependent on the estrogen-induced changes in consistency of the mucus described earlier. Furthermore, the sperm can usually survive for up to a day or two within the cervical mucus, from which they can be released to enter the uterus. One reason for this is that the vaginal environment is acidic, a protection against yeast and bacterial infections. Of the several hundred million sperm deposited in the vagina in an ejaculation, only about 100 to 200 usually reach the fallopian tube. This is the major reason there must be so many sperm in the ejaculate for fertilization to occur. Sperm are not able to fertilize the egg until they have resided in the female tract for several hours and been acted upon by secretions of the tract. Fertilization Fertilization begins with the fusion of a sperm and egg in the fallopian tube, usually within a few hours after ovulation. The zona pellucida glycoproteins function as receptors for sperm surface proteins. The sperm head has many of these proteins and so becomes bound simultaneously to many sperm receptors on the zona pellucida. This binding triggers what is termed the acrosome reaction in the bound sperm: the plasma membrane of the sperm head is altered so that the underlying membrane-bound acrosomal enzymes are now exposed to the outside-that is, to the zona pellucida. The enzymes digest a path through the zona pellucida as the sperm, using its tail, advances through this coating. Viability of the newly fertilized egg, now called a zygote, depends upon preventing the entry of additional sperm. The initial fusion of the sperm and egg plasma membranes triggers a reaction that changes membrane potential, preventing additional sperm from binding. The photograph on the first page of this chapter shows the actual size relationship between the sperm and the egg. Reproduction 625 inactivation of its sperm-binding sites and hardening of the entire zona pellucida. This prevents additional sperm from binding to the zona pellucida and those sperm already advancing through it from continuing. The two sets of chromosomes-23 from the egg and 23 from the sperm, which are surrounded by distinct membranes and are known as pronuclei-migrate to the center of the cell. Fertilization also triggers activation of enzymes required for the ensuing cell divisions and embryogenesis. If fertilization had not occurred, the egg would have slowly disintegrated and been phagocytized by cells lining the uterus. Rarely, a fertilized egg remains in a fallopian tube and embeds itself in the tube wall. Even more rarely, a fertilized egg may move backward out of the fallopian tube into the abdominal cavity, where implantation can occur. Both kinds of ectopic pregnancies cannot succeed, and surgery is necessary to end the pregnancy (unless there is a spontaneous abortion) because of the risk of maternal hemorrhage. The conceptus-a collective term for everything ultimately derived from the original zygote (fertilized egg) throughout the pregnancy-remains in the fallopian tube for 3 to 4 days. The major reason is that estrogen maintains the contraction of the smooth muscle near where the fallopian tube enters the wall of the uterus. As plasma progesterone concentrations increase, this smooth muscle relaxes and allows the conceptus to pass. During its stay in the fallopian tube, the conceptus undergoes a number of mitotic cell divisions, a process known as cleavage. These divisions, however, are unusual in that no cell growth occurs before each division; the 16- to 32-cell conceptus that reaches the uterus is essentially the same size as the original fertilized egg. Each of these cells is totipotent-that is, they are stem cells that have the capacity to develop into an entire individual. Therefore, identical (monozygotic) twins result when, at some point during cleavage, the dividing cells become completely separated into two independently growing cell masses. In contrast, as described earlier, dizygotic twins result when two eggs are ovulated and fertilized. After reaching the uterus, the conceptus floats free in the intrauterine fluid, from which it receives nutrients, for approximately 3 days, all the while undergoing further cell divisions to approximately 100 cells. Soon the conceptus reaches the stage known as a blastocyst, by which point the cells have lost their totipotentiality and have begun to differentiate. During subsequent development, the inner cell mass will give rise to the developing human-called an embryo during the first 2 months and a fetus after that-and some of the membranes associated with it. The trophoblast will surround the embryo and fetus throughout development and be involved in its nutrition as well as in the secretion of several important hormones. During this period, the uterine lining is being prepared by progesterone (secreted by the corpus luteum) to receive the blastocyst. The trophoblast cells are sticky, particularly in the region overlying the inner cell mass, and it is this portion of the blastocyst that adheres to the endometrium and initiates implantation. The initial contact between blastocyst and endometrium induces rapid proliferation of the trophoblast, the cells of which penetrate between endometrial cells. Proteolytic enzymes secreted by the trophoblast allow the blastocyst to bury itself in the endometrial layer. Implantation is soon completed, and the nutrientrich endometrial cells provide the metabolic fuel and raw materials required for early growth of the embryo. Trophoblast (a) Placentation this simple nutritive system, however, is only Blastocyst Inner cell mass Uterine wall (b) Invading trophoblast adequate to provide for the embryo during the first few weeks, when it is very small. The structure that takes over this function is the placenta, a combination of interlocking fetal and maternal tissues, which serves as the organ of exchange between mother and fetus for the remainder of the pregnancy. The embryonic portion of the placenta is supplied by the outermost layers of trophoblast cells, the chorion, and the maternal portion by the endometrium underlying the chorion. The endometrium around the villi is altered by enzymes and other paracrine molecules secreted from the cells of the invading villi so that each villus becomes completely surrounded by a pool, or sinus, of maternal blood supplied by maternal arterioles. Reproduction 627 Placenta Amniotic cavity Uterine vein and artery Gland in endometrium Endometrium Myometrium Branch of umbilical artery and vein Umbilical vein (to fetus) materials between the two bloodstreams but no mixing of the fetal and maternal blood. Umbilical veins carry oxygen and nutrientrich blood from the placenta to the fetus, whereas umbilical arteries carry blood with waste products and a low oxygen content to the placenta. Simultaneously, blood flows from the fetus into the capillaries of the chorionic villi via the umbilical arteries and out of the capillaries back to the fetus via the umbilical vein. All of these umbilical vessels are contained in the umbilical cord, a long, ropelike structure that connects the fetus to the placenta. Five weeks after implantation, the placenta has become well established; the fetal heart has begun to pump blood; the entire mechanism for nutrition of the embryo and, subsequently, fetus and the excretion of waste products is in operation. A layer of epithelial cells in the villi and of endothelial cells in the fetal capillaries separates the maternal and fetal blood. Waste products move from blood in the fetal capillaries across these layers into the maternal blood; nutrients, hormones, and growth factors move in the opposite direction. Others, such as glucose, use transport proteins in the plasma membranes of the epithelial cells. The epithelial layer lining the cavity is derived from the inner cell mass and is called the amnion, or amniotic sac. It eventually fuses with the inner surface of the chorion so that only a single combined membrane surrounds the fetus. The fluid in the amniotic cavity, the amniotic fluid, resembles the fetal extracellular fluid, and it buffers mechanical disturbances and temperature variations. The fetus, floating in the amniotic cavity and attached by the umbilical cord to the placenta, develops into a viable infant during the next 8 months. Amniotic fluid can be sampled by amniocentesis as early as the sixteenth week of pregnancy. Some genetic diseases can be diagnosed by the finding of certain chemicals either in the fluid or in sloughed fetal cells suspended in the fluid.

Syndromes

- Learning to slow down how the person talks

- Anyone with chronic heart, lung, or kidney conditions, diabetes, or a weakened immune system

- Damage to your kidney

- Feeling that food is stuck behind the breastbone

- An examination of discharge released from the breast to see if the cells are cancerous (malignant)

- Tube through the mouth into the stomach to wash out the stomach (gastric lavage)

- Being near the droplets or secretions from someone who sneezes, coughs, or has a runny nose

- Abdomen

- Fever

- Reptiles carry a type of bacteria called salmonella. If you own a reptile, wear gloves when handling the animal or its feces because salmonella is easily passed from animal to human.

Buy xenical 60mg amex

It may occur at any age but occurs most frequently in elderly persons; this is of great concern because of the likelihood of falling when dizzy and the fragility of the bones of many elderly persons weight loss keto diet purchase xenical online from canada. Otoliths may be dislodged by head injury or infection or due to the normal degeneration of aging. The head movements are designed to use the force of gravity to dislodge loose otoliths from the semicircular canals and move them back into the gelatinous membranes within the utricle and saccule. Because multiple treatments are sometimes required, he was given instructions on how to self-administer a modified Epley maneuver at home; within 3 weeks, his vertigo was gone. This multistep procedure helps restore loose otoliths to their normal position in the utricle and saccule of the inner ear, thereby alleviating vertigo. The modality of energy a given sensory receptor responds to in normal functioning is known as the "adequate stimulus" for that receptor. Receptor potentials are "all-or-none," that is, they have the same magnitude regardless of the strength of the stimulus. When the frequency of action potentials along sensory neurons is constant as long as a stimulus continues, it is called "adaptation. When sensory units have large receptive fields, the acuity of perception is greater. Using a single intracellular recording electrode, in what part of a sensory neuron could you simultaneously record both receptor potentials and action potentials When a stimulus is maintained for a long time, action potentials from sensory receptors decrease in frequency with time. Descending inputs from the brainstem inhibit afferent pain pathways in the spinal cord. Inhibitory interneurons decrease action potentials from receptors at the periphery of a stimulated region. The eyeball is too long; far objects focus on the retina when the ciliary muscle contracts. The eyeball is too long; near objects focus on the retina when the ciliary muscle is relaxed. The eyeball is too short; near objects focus on the retina when the ciliary muscle is relaxed. If a patient suffers a stroke that destroys the optic tract on the right side of the brain, which of the following visual defects will result There will be no vision in the left eye, but vision will be normal in the right eye. The patient will not perceive images of objects striking the left half of the retina in the left eye. The patient will not perceive images of objects striking the right half of the retina in the right eye. Displacement of the basilar membrane with respect to the tectorial membrane stimulates stereocilia on the hair cells. Pressure waves on the oval window cause vibrations of the malleus, which are transferred via the stapes to the round window. Movement of the stapes causes oscillations in the tympanic membrane, which is in contact with the endolymph. Oscillations of the stapes against the oval window set up pressure waves in the semicircular canals. A standing subject looking over her left shoulder suddenly rotates her head to look over her right shoulder. The utricle goes from a vertical to a horizontal position, and otoliths stimulate stereocilia. Stretch receptors in neck muscles send action potentials to the vestibular apparatus, which relays them to the brain. Fluid within the semicircular canals remains stationary, bending the cupula and stereocilia as the head rotates. The movement causes endolymph in the cochlea to rotate from right to left, stimulating inner hair cells. Describe several mechanisms by which pain could theoretically be controlled medically or surgically. At what two sites would central nervous system injuries interfere with the perception that heat is being applied to the right side of the body At what single site would a central nervous system injury interfere with the perception that heat is being applied to either side of the body Damage to what parts of the cerebral cortex could explain the following behaviors A key general principle of physiology is that homeostasis is essential for health and survival. How might sensory receptors responsible for detecting painful stimuli (nociceptors) contribute to homeostasis How does the sensory transduction mechanism in the vestibular and auditory systems demonstrate the importance of the general principle of physiology that controlled exchange of materials occurs between compartments and across cellular membranes Elaboration of surface area to maximize functional capability is a common motif in the body illustrating the general principle of physiology that structure is a determinant of-and has coevolved with-function. Action potential propagation to the central nervous system would also be normal because it depends only on voltage-gated Na1 and K1 channels. When pressure is initially applied, the fluid in the capsule compresses the neuron ending, opening mechanically gated nonspecific cation channels and causing depolarization and action potentials. However, fluid then redistributes within the capsule, taking the pressure off the neuron ending; consequently, the channels close and the neuron repolarizes. When the pressure is removed, redistribution of the capsule back to its original shape briefly deforms the neuron ending once again and a brief depolarization results. Without the specialized capsule, the afferent neuron ending becomes a slowly adapting receptor; as long as pressure is applied, the mechanoreceptors remain open and the receptor potential and action potentials persist. Lung infections are often accompanied by an accumulation of fluid in the lungs, which is detectable with a stethoscope as crackling or bubbling sounds during breathing. Below the level of the injury, however, there would be a mixed pattern of sensory loss. Fine touch, pressure, and body position sensation would be lost from the left side of the body below the level of the injury because that information ascends in the spinal cord on the side that it enters without crossing the midline until it reaches the brainstem. Pain and temperature sensation would be lost from the right side of the body below the injury because those pathways cross immediately upon entry and ascend in the opposite side of the spinal cord. Physical laws relate the wavelength and frequency of such radiation and determine its energy. Only certain wavelengths and energies are detected by the sensory apparatus of the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation that has more or less energy than a narrow band corresponding to a few hundred nanometers wavelength cannot be detected by the eye; this is what defines "visible" light. The frequency of the electromagnetic wave in this figure is [2 cycles/msec 3 1000 msec/sec] or 2 3 103 Hz (2000 cycles per second). It would not be visible, because visible light frequencies are in the range of 1014 to 1015 Hz. Because retinal is also used in cone photopigments, a severe vitamin A deficiency eventually results in impairment of vision under all lighting conditions, being generally most noticeable at night when less light is available. Left Eye Right Eye the left half of the visual field of each eye would be dark because neurons from the right half of each of the retinas would not reach the visual cortex. The outer half of the visual field seen by each eye would be dark because neurons from the inner half of the retinas that cross at the optic chiasm would not reach the visual cortex. The right half of the visual field seen by each eye would be perceived as dark because the left occipital lobe processes neuronal input from the left half of each retina. When you shift your gaze to the white background (white light contains all wavelengths of light), only the blue cones are available to respond, so you perceive a blue circle until the red and green cones recover. With those muscles contracted, the movement of the middle ear bones is dampened during the 140 dB gun blast, thus reducing the transmission of that harmfully loud sound to the inner ear. The energy is transferred to movement of the eardrum, which in turn transfers energy to the bones in the middle ear. That energy is transferred to the fluids of the inner ear, and then to the basilar membrane.

Purchase 120 mg xenical amex

As Chapter 13 describes weight loss 757 120mg xenical otc, at the base of the chest cavity (thorax) is a large muscle called the diaphragm, which separates the thorax from the abdomen. During inspiration of air, the diaphragm descends, pushing on the abdominal contents and increasing abdominal pressure. Simultaneously, the pressure in the thorax decreases, thereby decreasing the pressure in the intrathoracic veins and right atrium. The net effect of the pressure changes in the abdomen and thorax is to increase the pressure difference between the peripheral veins and the heart. Thus, venous return is enhanced during inspiration (expiration would reverse this effect if not for the venous valves), and breathing deeply and frequently, as in exercise, helps blood flow toward the heart. You might get the incorrect impression from these descriptions that venous return and cardiac output are independent entities. Venous return and cardiac output therefore must be the same except for transient differences over brief periods of time. The effects of increased inspiration on end-diastolic ventricular volume are actually quite complex, but for the sake of simplicity, they are shown here only as increasing venous pressure. During muscle contraction, venous diameter decreases and venous pressure increases. The increase in pressure forces the flow only toward the heart because backward pressure forces the valves in the veins to close. Present in the interstitium of virtually all organs and tissues are numerous lymphatic capillaries that are completely distinct from blood vessel capillaries. Like the latter, they are tubes made of only a single layer of endothelial cells resting on a basement membrane, but they have large water-filled channels that are permeable to all interstitial fluid constituents, including protein. The lymphatic capillaries are the first of the lymphatic vessels, for unlike the blood vessel capillaries, no tubes flow into them. Small amounts of interstitial fluid continuously enter the lymphatic capillaries by bulk flow. This lymph fluid flows from (a) Lymph capillaries (b) the lymphatic capillaries into the next set of lymphatic vessels, which converge to form larger and larger lymphatic vessels. Ultimately, the entire network ends in two large lymphatic ducts that drain into the veins near the junction of the jugular and subclavian veins in the upper chest. Valves at these junctions permit only one-way flow from lymphatic ducts into the veins. Therefore, the lymphatic vessels carry interstitial fluid to the circulatory system. The movement of interstitial fluid from the lymphatics to the circulatory system is very important because, as noted earlier, the amount of fluid filtered out of all the blood vessel capillaries (except those in the kidneys) exceeds that absorbed by approximately 4 L each day. In the process, small amounts of protein that may leak out of blood vessel capillaries into the interstitial fluid are also returned to the circulatory system. The arteries function as low-resistance conduits and as pressure reservoirs for maintaining blood flow to the tissues during ventricular relaxation. The difference between maximal arterial pressure (systolic pressure) and minimal arterial pressure (diastolic pressure) during a cardiac cycle is the pulse pressure. Mean arterial pressure can be estimated as diastolic pressure plus one-third of the pulse pressure. Arterioles are the dominant site of resistance to flow in the vascular system and have major functions in determining mean arterial pressure and in distributing flows to the various organs and tissues. Arteriolar resistance is determined by local factors and by reflex neural and hormonal input. Local factors that change with the degree of metabolic activity cause the arteriolar vasodilation and increased flow of active hyperemia. Flow autoregulation involves local metabolic factors and arteriolar myogenic responses to stretch, and it changes arteriolar resistance to maintain a constant blood flow when arterial blood pressure changes. Sympathetic neurons innervate most arterioles and cause vasoconstriction via a-adrenergic receptors. In certain cases, noncholinergic, nonadrenergic neurons that release nitric oxide or other vasodilators also innervate blood vessels. Epinephrine causes vasoconstriction or vasodilation, depending on the proportion of a-adrenergic and b2-adrenergic receptors in the organ. Some chemical inputs act by stimulating endothelial cells to release vasodilator or vasoconstrictor paracrine agents, which then act on adjacent smooth muscle. These paracrine agents include the vasodilators nitric oxide (endothelium-derived relaxing factor), prostacyclin, and the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1. Under some circumstances, the lymphatic system can become occluded, which allows the accumulation of excessive interstitial fluid. Surgical removal of lymph nodes and vessels during the treatment of breast cancer can similarly allow interstitial fluid to pool in affected tissues. In addition to draining excess interstitial fluid, the lymphatic system provides the pathway by which fat absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract reaches the blood (see Chapter 15). The lymphatics can also be the route by which cancer cells spread from their area of origin to other parts of the body (which is why cancer treatment sometimes includes the removal of lymph nodes). Capillaries are the site at which nutrients and waste products are exchanged between blood and tissues. Blood flows through the capillaries more slowly than through any other part of the vascular system because of the huge crosssectional area of the capillaries. Capillary blood flow is determined by the resistance of the arterioles supplying the capillaries and by the number of open precapillary sphincters. Diffusion is the mechanism that exchanges nutrients and metabolic end products between capillary plasma and interstitial fluid. Lipid-soluble substances can move through the endothelial cells, whereas ions and polar molecules only move through water-filled intercellular clefts or fused-vesicle channels. Plasma proteins do not easily move across capillary walls; specific proteins like certain hormones can be moved by vesicle transport. The diffusion gradient for a substance across capillaries arises as a result of cell utilization or production of the substance. Increased metabolism increases the diffusion gradient and increases the rate of diffusion. Bulk flow of protein-free plasma or interstitial fluid across capillaries determines the distribution of extracellular fluid between these two fluid compartments. Filtration from plasma to interstitial fluid is favored by the hydrostatic pressure difference between the capillary and the Mechanism of Lymph Flow In large part, the lymphatic vessels beyond the lymphatic capillaries propel the lymph within them by their own contractions. The smooth muscle in the wall of the lymphatics exerts a pumplike action by inherent rhythmic contractions. Because the lymphatic vessels have valves similar to those in veins, these contractions produce a oneway flow toward the point at which the lymphatics enter the circulatory system. The lymphatic vessel smooth muscle is responsive to stretch, so when no interstitial fluid accumulates and, therefore, no lymph enters the lymphatics, the smooth muscle is inactive. However, when increased fluid filtration out of capillaries occurs, the increased fluid entering the lymphatics stretches the walls and triggers rhythmic contractions of the smooth muscle. This constitutes a negative feedback mechanism for adjusting the rate of lymph flow to the rate of lymph formation and thereby preventing edema. In addition, the smooth muscle of the lymphatic vessels is innervated by sympathetic neurons, and excitation of these neurons in various physiological states such as exercise may contribute to increased lymph flow. These include the same external forces we described for veins-the skeletal muscle pump and respiratory pump. Absorption from interstitial fluid to plasma is favored by the protein concentration difference between the plasma and the interstitial fluid. Filtration and absorption do not change the concentrations of crystalloids in the plasma and interstitial fluid because these substances move together with water. There is normally a small excess of filtration over absorption, which returns fluids to the bloodstream via lymphatic vessels. Sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction reflexively reduces venous diameter to maintain venous pressure and venous return.

Buy discount xenical line

For example weight loss pills under 10 discount 120 mg xenical with visa, with the addition of a few enzymes, the pathway for fat synthesis is also used for synthesis of the phospholipids found in membranes. The material presented in this section should serve as a foundation for understanding how the body copes with changes in nutrient availability. Glycogen Storage A small amount of glucose can be stored in the body to provide a reserve supply for use when glucose is not being absorbed into the blood from the small intestine. Recall from Chapter 2 that it is stored as the polysaccharide glycogen, mostly in skeletal muscles and the liver. Each bowed arrow indicates one or more irreversible reactions that require different enzymes to catalyze the reaction in the forward and reverse directions. An additional series of reactions leads to the transfer of a four-carbon intermediate derived from oxaloacetate out of the mitochondria and its conversion to phosphoenolpyruvate in the cytosol. Phosphoenolpyruvate then reverses the steps of glycolysis back to the level of reaction 3, in which a different enzyme from that used in glycolysis is required to convert fructose 1,6-bisphosphate to fructose 6-phosphate. The enzymes for both glycogen synthesis and glycogen breakdown are located in the cytosol. Thus, glucose 6-phosphate can either be broken down to pyruvate or used to form glycogen. The existence of two pathways containing enzymes that are subject to both covalent and allosteric modulation provides a mechanism for regulating the flow between glucose and glycogen. When an excess of glucose is available to a liver or muscle cell, the enzymes in the glycogen-synthesis pathway are activated and the enzyme that breaks down glycogen is simultaneously inhibited. When less glucose is available, the reverse combination of enzyme stimulation and inhibition occurs, and net breakdown of glycogen to glucose 6-phosphate (known as glycogenolysis) ensues. This process of generating new molecules of glucose from noncarbohydrate precursors is known as gluconeogenesis. The major substrate in gluconeogenesis is pyruvate, formed from lactate as described earlier, and from several amino acids during protein breakdown. Note the points at which each of these precursors, supplied by the blood, enters the pathway. Many of the same enzymes are used in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, so the questions arise: What controls the direction of the reactions in these pathways What conditions determine whether glucose is broken down to pyruvate or whether pyruvate is converted into glucose The answers lie in the concentrations of glucose or pyruvate in a cell and in the control the enzymes exert in the irreversible steps in the pathway. This control is carried out via various hormones that alter the concentrations and activities of these key enzymes. For example, if blood glucose concentrations fall below normal, certain hormones are secreted into the blood and act on the liver. There, the hormones preferentially induce the expression of the gluconeogenic enzymes, thereby favoring the formation of glucose. Fat typically accounts for approximately 80% of the energy stored in the body (Table 3. Almost the entire cytoplasm of each of these cells is filled with a single, large fat droplet. Clusters of adipocytes form adipose tissue, most of which is in deposits underlying the skin or surrounding internal organs. The factors controlling fat storage and release from adipocytes during different physiological states will be described in Chapter 16. The breakdown of a fatty acid is initiated by linking a molecule of coenzyme A to the carboxyl end of the fatty acid. Each passage through this sequence shortens the fatty acid chain by two carbon atoms until all the carbon atoms have transferred to coenzyme-A molecules. If an average person stored most of his or her energy as carbohydrate rather than fat, body weight would have to be approximately 30% greater in order to store the same amount of usable energy, and the person would consume more energy moving this extra weight around. Thus, a major step in energy economy occurred when animals evolved the ability to store energy as fat. Therefore, glucose can readily be metabolized and used to synthesize fat, but the fatty acid portion of fat cannot be used to synthesize glucose. Protein and Amino Acid Metabolism In contrast to the complexities of protein synthesis, protein catabolism requires only a few enzymes, collectively called proteases, to break the peptide bonds between amino acids (a process called proteolysis). Some of these enzymes remove one amino acid at a time from the ends of the protein chain, whereas others break peptide bonds between specific amino acids within the chain, forming peptides rather than free amino acids. Because there are 20 different amino acids, a large number of intermediates can be formed, and there are many pathways for processing them. A few basic types of reactions common to most of these pathways can provide an overview of amino acid catabolism. Unlike most carbohydrates and fats, amino acids contain nitrogen atoms (in their amino groups) in addition to carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. Once the nitrogen-containing amino group is removed, the remainder of most amino acids can be metabolized to intermediates capable of entering either the glycolytic pathway or the Krebs cycle. The second means of removing an amino group is known as transamination and involves transfer of the amino group from an amino acid to a keto acid. Note that the keto acid to which the amino group is transferred becomes an amino acid. Cells can also use the nitrogen derived from amino groups to synthesize other important nitrogen-containing molecules, such as the purine and pyrimidine bases found in nucleic acids. Note that the keto acids formed are intermediates either in the Krebs cycle (a-ketoglutaric acid) or glycolytic pathway (pyruvic acid). Once formed, these keto acids can be metabolized Fat Synthesis the synthesis of fatty acids occurs by reactions that are almost the reverse of those that degrade them. However, the enzymes in the synthetic pathway are in the cytosol, whereas (as we have just seen) the enzymes catalyzing fatty acid breakdown are in the mitochondria. Fatty acid synthesis begins with cytoplasmic acetyl coenzyme A, which transfers its acetyl group to another molecule of acetyl coenzyme A to form a four-carbon chain. By repetition of this process, long-chain fatty acids are built up two carbons at a time. This accounts for the fact that all the fatty acids synthesized in the body contain an even number of carbon atoms. Once the fatty acids are formed, triglycerides can be synthesized by linking fatty acids to each of the three hydroxyl groups in glycerol, more specifically, to a phosphorylated form of glycerol called glycerol 3-phosphate. The synthesis of triglyceride is carried out by enzymes associated with the membranes of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum. Compare the molecules produced by glucose catabolism with those required for synthesis of both fatty acids and glycerol 3-phosphate. First, acetyl coenzyme A, the starting material for fatty acid synthesis, can be formed from pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis. It should not be surprising, therefore, that much of the carbohydrate in food is converted into fat and stored in adipose tissue shortly after its absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. Importantly, fatty acids-or, more specifiOxidative deamination cally, the acetyl coenzyme A derived from fatty acid breakdown-cannot be used to synthesize O new molecules of glucose. First, because the reaction in which pyruvate is broken down to aceAmino acid Keto acid Ammonia tyl coenzyme A and carbon dioxide is irreversible, acetyl coenzyme A cannot be converted into Transamination pyruvate, a molecule that could lead to the production of glucose. A very small quantity of amino acids and protein is lost from the body via the urine; skin; hair; fingernails; and, in women, the menstrual fluid. The major route for the loss of amino acids is not their excretion but rather their deamination, with the eventual excretion of the nitrogen atoms as urea in the urine. The terms negative nitrogen balance and positive nitrogen balance refer to whether there is a net loss or gain, respectively, of amino acids in the body over any period of time. If any of the essential amino acids are missing from the diet, a negative nitrogen balance-that is, loss greater than gain- always results. The proteins that require a missing essential amino acid cannot be synthesized, and the other amino acids that would have been incorporated into these proteins are metabolized. This explains why a dietary requirement for protein cannot be specified without regard to the amino acid composition of that protein. Protein is graded in terms of how closely its relative proportions of essential amino acids approximate those in the average body protein. The highest-quality proteins are found in animal products, whereas the quality of most plant proteins is lower.

120 mg xenical with visa

Afferent neuron cell bodies are located in dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord for sensory inputs from the body and cranial nerve ganglia for sensory inputs from the head weight loss foods cheap 120 mg xenical with mastercard. All the receptors of a single afferent neuron are preferentially sensitive to the same type of stimulus; for example, they are all sensitive to cold or all to pressure. Because the receptive fields for different modalities overlap, a single stimulus, such as an ice cube on the skin, can simultaneously give rise to the sensations of touch and temperature. Stimulus Location A third feature of coding is the location of the stimulus-in other words, where the stimulus is being applied. It should be noted that in vision, hearing, and smell, stimulus location is interpreted as arising from the site from which the stimulus originated rather than the place on our body where the stimulus was actually applied. For example, we interpret the sight and sound of a barking dog as arising from the dog in the yard rather than in a specific region of our eyes and ears. We will have more to say about this later; we deal here with the senses in which the stimulus is localized to a site on the body. Locating sensations from internal organs is less precise than from the skin because there are fewer afferent neurons in the internal organs and each has a larger receptive field. Stimulus Intensity How do we distinguish a strong stimulus from a weak one when the information about both stimuli is relayed by action potentials that are all the same amplitude As the strength of a local stimulus increases, receptors on adjacent branches of an afferent neuron are activated, resulting in a summation of their local currents. In addition to increasing the firing frequency in a single afferent neuron, stronger stimuli usually affect a larger area and activate similar receptors on the endings of other afferent neurons. For example, when you touch a surface lightly with a finger, the area of skin in contact with the surface is small, and only the receptors in that skin area are stimulated. This "calling in" of receptors on additional afferent neurons is known as recruitment. However, more subtle mechanisms also exist that allow us to localize distinct stimuli within the receptive field of a single neuron. In some cases, receptive field overlap aids stimulus localization even though, intuitively, overlap would seem to "muddy" the image. Central nervous system Importance of Receptor Field Overlap An afferent neuron responds most vigorously to stimuli applied at the center of its receptive field because the receptor density-that is, the number of its receptor endings in a given area-is greatest there. The response decreases as the stimulus is moved toward the receptive field periphery. The firing frequency of the afferent neuron is also related to stimulus strength, however. Therefore, neither the intensity nor the location of the stimulus can be detected precisely with a single afferent neuron. The density of receptor terminals around area A is greater than around B, so the frequency of action potentials in response to a stimulus in area A will be greater than the response to a similar stimulus in B. The afferent neuron in the center (B) has a higher initial firing frequency than do the neurons on either side (A and C). The number of action potentials transmitted in the lateral pathways is further decreased by inhibitory inputs from inhibitory interneurons stimulated by the central neuron. Although the lateral afferent neurons (A and C) also exert inhibition on the central pathway, their lower initial firing frequency has a smaller inhibitory effect on the central pathway. Lateral inhibition can be demonstrated by pressing the tip of a pencil against your finger. Exact localization is possible because lateral inhibition removes the information from the peripheral regions. Lateral inhibition is utilized to the greatest degree in the pathways providing the most accurate localization. For example, lateral inhibition within the retina of the eye creates amazingly sharp visual acuity, and skin hair movements are also well-localized due to lateral inhibition between parallel pathways ascending to the brain. On the other hand, neuronal pathways carrying temperature and pain information do not have significant lateral inhibition, so we locate these stimuli relatively poorly. Once this location is known, the brain can interpret the firing frequency of neuron B to determine stimulus intensity. Because the central fiber B at the beginning of the pathway (bottom of figure) is firing at the highest frequency, it inhibits the lateral neurons (via inhibitory interneurons) to a greater extent than the lateral neurons inhibit the central pathway. Skin Area of receptor activation In some cases, for example, in the pain pathways, the afferent input is continuously inhibited to some degree. This provides the flexibility of either removing the inhibition, so as to allow a greater degree of signal transmission, or increasing the inhibition, so as to block the signal more completely. Therefore, the sensory information that reaches the brain is significantly modified from the basic signal originally transduced into action potentials at the sensory receptors. The neuronal pathways within which these modifications take place are described next. The sensory unit under the tip inhibits additional stimulated units at the edge of the stimulated area. Lateral inhibition produces a central area of excitation surrounded by an area in which the afferent information is inhibited. The sensation is localized to a more restricted region than that in which all three units are actually stimulated. Central Control of Afferent Information All sensory signals are subject to extensive modification at the various synapses along the sensory pathways before they reach higher levels of the central nervous system. The reticular formation and cerebral cortex (see Chapter 6), in particular, control the input of afferent information via descending pathways. These chains of neurons travel in bundles of parallel pathways carrying information into the central nervous system. Some pathways terminate in parts of the cerebral cortex responsible for conscious recognition of the incoming information; others carry information not consciously perceived. Sensory pathways are also called ascending pathways because they project "up" to the brain. The central processes of the afferent neurons enter the brain or spinal cord and synapse upon interneurons there. The interneurons upon which the afferent neurons synapse are called second-order neurons, and these in turn synapse with third-order neurons, and so on, until the information (coded action potentials) reaches the cerebral cortex. Most sensory pathways convey information about only a single type of sensory information. For example, one pathway conveys information only from mechanoreceptors, whereas another is influenced by information only from thermoreceptors. The olfactory cortex is located toward the midline on the undersurface of the frontal lobes (not visible in this picture). Association areas are not part of sensory pathways, but have related functions described shortly. In other words, they indicate that something is happening, without specifying just what or where. A given ascending neuron in a nonspecific ascending pathway may respond, for example, to input from several afferent neurons, each activated by a different stimulus, such as maintained skin pressure, heating, and cooling. The nonspecific ascending pathways, as well as collaterals from the specific ascending pathways, end in the brainstem reticular formation and regions of the thalamus and Cerebral cortex Thalamus and brainstem information even though all of it is being transmitted by essentially the same signal, the action potential. The ascending pathways in the spinal cord and brain that carry information about single types of stimuli are known as the specific ascending pathways. Thus, information from receptors on the right side of the body is transmitted to the left cerebral hemisphere, and vice versa. The specific ascending pathways that transmit information from somatic receptors project to the somatosensory cortex. Somatic receptors are those carrying information from the skin, skeletal muscle, bones, tendons, and joints. The specific ascending pathways from the eyes connect to a different primary cortical receiving area, the visual cortex, which is in the occipital lobe. The specific ascending pathways from the ears go to the auditory cortex, which is in the temporal lobe. Specific ascending pathways from the taste buds pass to the gustatory cortex adjacent to the region of the somatosensory cortex where information from the face is processed. The pathways serving olfaction project to portions of the limbic system and the olfactory cortex, which is located on the undersurface of the frontal and temporal lobes. Finally, the processing of afferent information does not end in the primary cortical receiving areas but continues from these areas to association areas in the cerebral cortex where complex integration occurs.

Cramp Bark. Xenical.

- What is Cramp Bark?

- How does Cramp Bark work?

- Are there safety concerns?

- Dosing considerations for Cramp Bark.

- Cramps, muscle spasms, menstrual cramps, cramps during pregnancy, use as a kidney stimulant in urinary conditions which involve pain or spasms, cancer, hysteria, nervous disorders, and many other conditions.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96728

Buy generic xenical 120 mg line

When ventricular contraction ends weight loss pills news 120mg xenical for sale, the stretched arterial walls recoil passively like a deflating balloon, and blood continues to be driven into the arterioles during diastole. The next ventricular contraction occurs while the artery walls are still stretched by the remaining blood. Arterial pressure is generally 390 Chapter 12 recorded as systolic/diastolic, which would be 120/80 mmHg in the example shown. Both systolic pressure and diastolic pressure average about 10 mmHg lower in females than in males. The difference between systolic pressure and diastolic pressure (120 2 80 5 40 mmHg in the example) is called the pulse pressure. It can be felt as a pulsation or throb in the arteries of the wrist or neck with each heartbeat. During diastole, nothing is felt over the artery, but the rapid increase in pressure at the next systole pushes out the artery wall; it is this expansion of the vessel that produces the detectable pulse. The most important factors determining the magnitude of the pulse pressure are (1) stroke volume, (2) speed of ejection of the stroke volume, and (3) arterial compliance. Specifically, the pulse pressure produced by a ventricular ejection is greater if the volume of blood ejected increases, if the speed at which it is ejected increases, or if the arteries are less compliant. As compliance changes, systolic and diastolic pressures also change but in opposite directions. For example, a person with a low arterial compliance (due to arteriosclerosis) but an otherwise normal circulatory system will have a large pulse pressure due to elevated systolic pressure and lowered diastolic pressure. Pulse pressure is therefore a better diagnostic indicator of arteriosclerosis than mean arterial pressure. An inflatable cuff containing a pressure gauge is wrapped around the upper arm, and a stethoscope is placed over the brachial artery just below the cuff. The high pressure in the cuff is transmitted through the tissue of the arm and completely compresses the artery under the cuff, thereby preventing blood flow through the artery. The air in the cuff is then slowly released, causing the pressure in the cuff and on the artery to decrease. When cuff pressure has decreased to a value just below the systolic pressure, the artery opens slightly and allows blood flow for a brief time at the peak of systole. During this interval, the blood flow through the partially compressed artery occurs at a very high velocity because of the small opening and the large pressure difference across the opening. Thus, the pressure at which sounds are first heard as the cuff pressure decreases is identified as the systolic blood pressure. As the pressure in the cuff decreases further, the duration of blood flow through the artery in each cycle becomes longer. When the cuff pressure reaches the diastolic blood pressure, all sound stops because flow is continuous and nonturbulent through the open artery. Therefore, diastolic pressure is identified as the cuff pressure at which sounds disappear. It should be clear from this description that the sounds heard during measurement of blood pressure are not the same as the heart sounds described earlier, which are due to closing of cardiac valves. How would you estimate the mean arterial blood pressure (from systolic and diastolic pressures) at a heart rate in which the times spent in systole and diastole are roughly equal We can say mean "arterial" pressure without specifying which artery we are referring to because the aorta and other large arteries have such large diameters that they offer negligible resistance to flow, and the mean pressures are therefore similar everywhere in the large arteries of a person who is lying down (gravitational effects in the upright posture will be considered in Section E). Sounds are first heard when cuff pressure falls just below systolic pressure, and they cease when cuff pressure falls below diastolic pressure. The lengths of the tubes are the same and the viscosity of the fluid is constant, so differences in resistance are due solely to differences in the radii of the tubes. If the radius of each tube can be independently altered, the blood flow through each is independently controlled. The tank is analogous to the major arteries, which serve as a pressure reservoir but are so large that they contribute little resistance to flow. Therefore, all the large arteries of the body can be considered a single pressure reservoir. The arteries branch within each organ into progressively smaller arteries, which then branch into arterioles. The smallest arteries are narrow enough to offer significant resistance to flow, but the still narrower arterioles are the major sites of resistance in the vascular tree and are therefore analogous to the outflow tubes 392 Chapter 12 in the model. Pulse pressure also decreases in the arterioles, so flow is much less pulsatile in downstream capillaries, venules, and veins. Arterioles contain smooth muscle, which can either relax and cause the vessel radius to increase (vasodilation), or contract and decrease the vessel radius (vasoconstriction). Therefore, the pattern of blood-flow distribution depends upon the degree of arteriolar smooth muscle contraction within each organ and tissue. In (a), blood flow is high through tube 2 and low through tube 3, whereas just the opposite is true for (b). This distribution can change greatly when the various resistances are changed, as occurs during exercise (discussed in Section E). Arteriolar smooth muscle possesses a large degree of spontaneous activity (that is, contraction independent of any neural, hormonal, or paracrine input). This spontaneous contractile activity is called intrinsic tone (also called basal tone). It sets a baseline level of contraction that can be increased or decreased by external signals, such as neurotransmitters and circulating hormones. An increase in contractile force above the intrinsic tone causes vasoconstriction, whereas a decrease in contractile force causes vasodilation. The mechanisms controlling vasoconstriction and vasodilation in arterioles fall into two general categories: (1) local controls and (2) extrinsic (or reflex) controls. Active Hyperemia Most organs and tissues manifest an Local Controls the term local controls denotes mechanisms independent of nerves or hormones by which organs and tissues alter their own arteriolar resistances, thereby self-regulating their blood flows. For example, the blood flow to exercising skeletal muscle increases in direct proportion to the increased activity of the muscle. Active hyperemia is the direct result of arteriolar dilation in the more active organ or tissue. The factors that cause arteriolar smooth muscle to relax in active hyperemia are local chemical changes in the extracellular fluid surrounding the arterioles. These result from the increased metabolic activity in the cells near the arterioles. The relative contributions of the different factors implicated vary, depending upon the organs involved and on the duration of the increased activity. Therefore, we will list-but not attempt to quantify-the local chemical changes that occur in the extracellular fluid. A number of other chemical factors increase when metabolism increases, including 1. Decreases in metabolic activity or increases in blood pressure would produce changes opposite those shown here. Initially, arterial pressure and flow through the arteriole are constant, but then the arterial pressure is experimentally increased and maintained at a higher level. How will blood flow through the arteriole change in the minutes that follow the increase in arterial pressure Local changes in all these chemical factors have been shown to cause arteriolar dilation under controlled experimental conditions, and they all probably contribute to the active-hyperemia response in one or more organs. It is likely, moreover, that additional important local factors remain to be discovered. All these chemical changes in the extracellular fluid act locally upon the arteriolar smooth muscle, causing it to relax. It should not be too surprising that active hyperemia is most highly developed in skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands- tissues that show the widest range of normal metabolic activities in the body. It is highly efficient that their supply of blood is primarily determined locally.

60mg xenical

Patients with severe uncontrolled type 1 diabetes mellitus produce large quantities of certain organic acids weight loss pills target generic xenical 60 mg online. A general principle of physiology highlighted throughout this chapter is that physiological processes are dictated by the laws of chemistry and physics. What are some examples of how this applies to lung mechanics and the transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide in blood How is the anatomy of the alveoli and pulmonary capillaries an example of the general principle of physiology that structure is a determinant of-and has coevolved with-function A general principle of physiology is that most physiological functions are controlled by multiple regulatory systems, often working in opposition. What are some examples of factors that have opposing regulatory effects on alveolar ventilation in humans These processes result in a net gain of oxygen (250 mL/per min at rest) from the atmosphere for consumption in the cells, and the net loss of carbon dioxide (200 mL/min at rest) from the cells to the atmosphere. In a normal region of the lung, there is a large safety factor such that a large increase in blood flow still allows normal oxygen uptake. However, even small increases in the rate of capillary blood flow in a diseased portion of the lung will decrease oxygen uptake due to a loss of this safety factor. Carotid body removal did not help in the treatment of asthma, and this approach was abandoned. The inability to adequately increase alveolar ventilation at altitude can result in harmful consequences leading to organ damage and even death. The negative pressure decreases Pip below Patm and thereby increases P tp, which results in re-expansion of the lung. This can be done with positive airway pressure generated by mechanical ventilation, which will increase Palv. This approach can work but also increases the risk of pneumothorax by inducing air leaks from the lung into the intrapleural space. To support the net uptake of oxygen and net removal of carbon dioxide, oxygen must be transferred from the atmosphere to all of the cells and organs of the body while carbon dioxide must be transferred from the cells to the atmosphere. This personalized adaptive learning tool serves as a guide to your reading by helping you discover which aspects of respiratory physiology you have mastered, and which will require more attention. A fascinating view inside real human bodies that also incorporates animations to help you understand respiratory physiology. You have also learned about how the maintenance of hydration is important in cardiovascular function in Chapter 12. We now deal with the regulation of body water volume and balance, and the inorganic ion composition of the internal environment. The urinary system in humans consists of all of the structures involved in removing soluble waste products from the blood and forming the urine; this includes the two kidneys, two ureters, the urinary bladder, and the urethra. Regulation of the total-body balance of any substance can be studied in terms of the balance concept described in Chapter 1. Theoretically, a substance can appear in the body either as a result of ingestion or synthesized as a product of metabolism. On the loss side of the balance, a substance can be excreted from the body or can be broken down by metabolism. If the quantity of any substance in the body is to be maintained over a period of time, the total amounts ingested and produced must equal the total amounts excreted and broken down. Reflexes that alter excretion via the urine constitute the major mechanisms that regulate the body balances of water and many of the inorganic ions that determine the properties of the extracellular fluid. Typical values for the extracellular concentrations of these ions appeared in Table 4. We will first describe the general principles of kidney function, then apply this information to how the kidneys process specific substances like Na1, H2O, H1, and K1 and participate in reflexes that regulate these substances. As you read about the structure, function, and control of the function of kidney, you will encounter numerous examples of the general principles of physiology that were outlined in Chapter 1. The regulation of the excretion of metabolic wastes, as well as the ability of the kidneys to reclaim needed ions and organic molecules that would otherwise be lost in the process, is a hallmark of the general principle of physiology that homeostasis is essential for health and survival; failure of kidney function not only causes a buildup of toxic waste products in the body but can also lead to a loss of important ions and nutrients (such as glucose and amino acids) in the urine. Another general principle of physiology-that most physiological functions are controlled by multiple regulatory systems, often working in opposition-is apparent in the renal system. The general principle of physiology that controlled exchange of materials occurs between compartments and across cellular membranes is also integral to this chapter-as already mentioned, total-body balance of important nutrients and ions is precisely controlled by the healthy kidneys. Finally, the functional unit of the kidney- the nephron-and the blood vessels associated with it are elegant examples of the general principle of physiology that structure is a determinant of-and has coevolved with-function; form and function are inextricably intertwined. Finally, the kidneys act as endocrine glands, releasing at least two hormones: erythropoietin (described in Chapter 12), and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (described in Chapter 11). They do so by excreting just enough water and inorganic ions to keep the amounts of these substances in the body within a narrow range. For example, if you increase your consumption of NaCl (common known as table salt), your kidneys will increase the amount of the Na1 and Cl2 excreted to match the intake. Alternatively, if there is not enough Na1 and Cl2 in the body, the kidneys will reduce the excretion of these ions. Second, the kidneys excrete metabolic waste products into the urine as fast as they are produced. These metabolic wastes include urea from the catabolism of protein, uric acid from nucleic acids, creatinine from muscle creatine, the end products of hemoglobin breakdown (which give urine much of its color), and many others. They are retroperitoneal, meaning they are just behind the peritoneum, the lining of this cavity. Renin, an enzyme that controls the formation of angiotensin, which influences blood pressure and sodium balance (this chapter) C. Conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, which influences calcium balance (Chapter 11) hilum, through which courses the blood vessels perfusing (renal artery) and draining (renal vein) the kidneys. The nerves that innervate the kidney and the tube that drains urine from the kidney (the ureter) also pass through the hilum. The ureter is formed from the calyces (singular, calyx), which are funnel-shaped structures that drain urine into the renal pelvis, from where the urine enters the ureter. Also notice that the kidney is surrounded by a protective capsule made of connective tissue. The kidney is divided into an outer renal cortex and inner renal medulla, described in more detail later. The connection between the tip of the medulla and the calyx is called the papilla. Each kidney contains approximately 1 million similar functional units called nephrons. The renal tubule is a very narrow, fluid-filled cylinder made up of a single layer of epithelial cells resting on a basement membrane. It is customary, however, to group two or more contiguous tubular segments when discussing function, and we will follow this practice. The renal corpuscle forms a filtrate from blood that is free of cells, larger polypeptides, and proteins. Ultimately, the fluid remaining at the end of each nephron combines in the collecting ducts and exits the kidneys as urine. The renal corpuscle is a classic example of the general principle of physiology that structure is a determinant of function. Not only do the many capillaries in each corpuscle greatly increase the surface area for filtration of waste products from the plasma but their structure creates an efficient sieve for the ultrafiltration of plasma. Each glomerulus is supplied with blood by an arteriole called an afferent arteriole. The renal artery enters, and the renal vein and ureter exit through the hilum (not labeled). The macula densa is not a distinct segment but a plaque of cells in the ascending loop of Henle where the loop passes between the arterioles supplying its renal corpuscle of origin. In the medulla, the loops of Henle and collecting ducts run parallel to each other. Two types of nephrons are shown-the juxtamedullary nephrons have long loops of Henle that penetrate deeply into the medulla, whereas the cortical nephrons have short (or no) loops of Henle.

Discount xenical 60 mg mastercard