Order 20 mg crestor visa

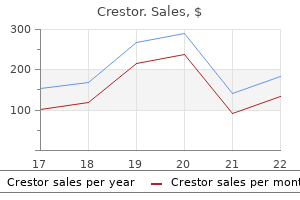

Chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies and pressor receptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch also give rise to afferent autonomic fibers cholesterol vitamin d order crestor. Whereas the fibers from the carotid sinus and carotid body travel via the glossopharyngeal nerve, those from the aortic body and aortic arch travel via the vagus nerve. Other receptors in the nose and nasal sinuses give rise to afferent fibers that form parts of the trigeminal and glossopharyngeal nerves. In addition, the respiratory centers are controlled to some extent by impulses from the hypothalamus and higher centers as well as from the reticular activating system. This parasympathetic efferent pathway carries motor impulses to the smooth muscle and glands of the tracheobronchial tree. Fibers carrying impulses to the larynx and upper trachea ascend in the sympathetic trunk and synapse in the cervical sympathetic ganglia with postganglionic fibers to those structures. The remainder synapse in the upper thoracic ganglia of the sympathetic trunks, from where the postganglionic fibers pass to the lower trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles, largely via the pulmonary plexus. Sympathetic stimulation relaxes bronchial and bronchiolar smooth muscle, inhibits glandular secretion, and causes vasoconstriction. Pharmacologic studies indicate that there are two types of adrenergic receptors, and. Stimulation may be inhibitory (relaxation of bronchial smooth muscle) or excitatory (increase in both heart rate and force of contraction). In the lungs, 2 stimulation (there are no 1 receptors there) cause bronchodilatation and possibly decreased secretion of mucus; adrenergic stimulation by pharmacologic agents causes bronchoconstriction. About 20 C-shaped plates of cartilage support the anterior and lateral walls of the trachea and main bronchi. Mucous glands are particularly numerous in the posterior aspect of the tracheal mucosa. More distally, the bands of elastic fibers are thinner and surround the entire circumference of the airways. Just above the point at which the main bronchus enters the lung, the cartilage plates come together to completely encircle the airway. The plates are no longer C-shaped but are smaller, more irregular, and arranged around the entire bronchial wall. At the level where cartilage completely surrounds the circumference of the airway, the muscle coat undergoes a striking rearrangement. It no longer inserts into the cartilage (as in the trachea) but forms a separate layer of interlacing bundles internal to it. The right main bronchus is shorter and less sharply angled away from the trachea than the left. A segment is not a functional end unit in the lung because it is not isolated by connective tissue. The pleura isolates one lobe from another, but because the main or oblique fissure is complete in only about 50% of subjects, even a lobe is not always an end unit. For counting orders or generations of airways, it is sometimes appropriate to count the trachea as the first generation, the main bronchi as the second generation, and so on. Bronchioles are distal to the bronchi beyond the last plate of cartilage and proximal to the alveolar region. Cartilage plates become sparser toward the periphery of the lung, and in the last generations of bronchi, plates are found only at the points of branching. The large bronchi have enough inherent rigidity to sustain patency even during massive lung collapse; the small bronchi collapse along with the bronchioles and alveoli. When any airway is pursued to its distal limit, the terminal bronchiole is reached. The acinus, or respiratory unit, of the lung is defined as the lung tissue supplied by a terminal bronchiole. Within the acinus, three to eight generations of respiratory bronchioles may be found. Collateral air passage occurs between acinus and acinus and between lobule and lobule through the pores of Kohn in the alveolar wall and through respiratory bronchioles between adjacent alveoli. They are lined throughout their length by pseudostratified, ciliated, columnar epithelium (also referred to as respiratory epithelium) supported by a basement membrane (see Plate 1-24 for details of cell types and their arrangement). The remainder of the wall includes a muscle coat and accessory structures such as submucosal glands, together with connective tissue. These measurements vary with age and the size of the individual and with the functional state of the airway. The epithelium is thicker in the larger airways and gradually thins toward the periphery of the lung. Immediately beneath the basement membrane, elastic fibers are collected into fine bands that form longitudinal ridges. Intraepithelial nerve endings that are almost certainly sensory fibers have also been described, but whether there are also motor nerve endings at the epithelial level is uncertain. Functional interaction between the two is probably very important at this level, and inflammation spreads easily through the walls of the small airways. In the smaller peripheral airways, the epithelium may be only a single layer thick and cuboidal rather than columnar because basal cells are absent at this level. Ciliated cells are present in even the smallest airways and respiratory bronchioles, where they are adjacent to alveolar lining cells. The feet of the axonemes are arranged so that a cilium "plugs" into the cytoplasm. The axonemes are attached to each other by "arms" of dynein, a contractile protein, and these provide the mechanism for ciliary motion. The brush cell resembles a similar cell type found in the gut and in the nasal sinuses. The mucous (goblet) cell is a secretory cell containing numerous large and confluent secretory granules. The serous cell resembles the serous cell of the submucosal gland and contains small, discrete, electrondense secretory granules. The Clara cell also contains small, discrete, electrondense granules, but compared with the serous cell, the Axial filament complex Nerve Ciliated cells Goblet (mucous) cell Nerves Ciliated cells Basal cell Clara cell Basement membrane Clara cell Cross section Magnified detail of cilium Electron micrograph of cilia Bronchioles. Ciliated cells dominant and Clara cells progressively increase distally along airways. Their vesicle content suggests that the fibers are sensory or motor and either cholinergic or adrenergic in type. The origin is referred to as the ciliated duct and is lined by bronchial epithelium with its mixed population of cells. It passes obliquely from the airway lumen, so the usual macroscopic section does not include the full length of the duct. It is usually seen as a rather large "acinus" composed of cells without secretory granules. Outpouchings or short-sided tubules may arise from the sides of the mucous tubules, and these are lined by serous cells. In addition to the cell types described above, the following are found: (1) myoepithelial cells; (2) "clear" cells; and (3) nerve fibers, including motor fibers. Outside the basement membrane, there are rich vascular and lymphatic networks and the nerve plexus. In histologic cross-sections, the submucosal gland is seen as a compact structure. Small, discrete electron-dense granules Submucosal glands Cartilage myoepithelial cell basement membrane nerve Light micrograph of submucosal glands than one-third the thickness of the airway wall (measured from the luminal surface to the cartilage layer). This ratio is similar in both children and adults and is consistent throughout airways at various levels of branching. The concentration of bronchial submucosal openings in the trachea is on the order of one gland opening per mm2. Blood from the lungs is drained by two venous systems, pulmonary and true bronchial. The pulmonary artery branches run with airways and their accompanying bronchial arteries in a single connective tissue sheath referred to as the bronchoarterial or bronchovascular bundle. They open if blood flow is interrupted in either system and in certain disease states such as pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. We now know that, even at its narrowest, the boundary between blood and air is composed of at least two cell types (the type I alveolar epithelial cell and the endothelial cell) and extracellular material, namely, the surfactant lining of the alveolar surface, the basement membranes, and the so-called "endothelial fuzz. Plate 1-27 shows part of a terminal airspace and cross sections of surrounding capillaries. Each alveolus (there are 300 million alveoli in the adult human lungs) may be associated with as many as 1000 capillary segments.

Buy crestor with american express

Eosinophilic oxyphilic cells are distinguished by their abundant cytoplasm cholesterol ratio most important purchase cheap crestor on-line, oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and closely packed mitochondria. Total thyroidectomy with ipsilateral central neck lymph node dissection is the most common treatment approach. The patient can often give the exact date of onset (usually a very recent one) and describes rapid growth causing pressure symptoms, dyspnea, dysphagia, hoarseness, cough, and even tenderness or pain in the mass. Systemic symptoms of weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, and fever may also be present. Histologically, this tumor is a solid, highly anaplastic growth, with spindle cells predominating but with many large giant cells occurring throughout the tumor. Gastrointestinal tract (colon, esophagus, stomach) Metastatic disease to the thyroid is common; it likely relates to its rich blood supply of approximately 560 mL/100 g tissue/min (a flow rate per gram of tissue that is second only to the adrenal glands). The prevalence of metastases to the thyroid gland in autopsy series varies from 1. The most common organ locations for the primary malignancy (in order of frequency) are the kidney (clear cell), lung, breast, head and neck, gastrointestinal tract (colon, esophagus, stomach), and skin (melanoma). Although there is no consensus on the role for surgery in these patients, most endocrinologists and endocrine surgeons recommend thyroid lobectomy. Although it is usually a palliative procedure, aggressive surgical treatment of thyroid metastases in the patients with isolated metastatic renal cell carcinoma have been curative. Radiotherapy may be considered for treatment of metastases that cannot be completely resected. Systemic chemotherapy may be indicated when there are multiple other sites of metastatic disease. Each adrenal gland consists of two parts-the cortex and medulla-that are enveloped in a common capsule. From the fifth to sixth week of embryogenesis, the cortical portion of each adrenal gland begins as a proliferation of cells, which originate from the coelomic cavity lining adjacent to the urogenital ridge. The cells proliferate rapidly and penetrate the retroperitoneal mesenchyme to form the primitive cortex. The primitive, or fetal, cortex constitutes the chief bulk of the adrenal glands at birth. The outer permanent cortex, which is thin at birth, begins to differentiate as the inner primitive cortex undergoes involution. The differentiation of the adrenal cortex is dependent on the temporal expression of transcription factors. By the middle of fetal life, some of the chromaffin cells have migrated to the central position within the cortex. When they are present, they may be within the celiac plexus or embedded in the cortex of the kidney. Adrenal rests, composed of only cortical tissue, occur frequently and are usually located near the adrenal glands. In adults, accessory separate cortical or medullary tissue may be present in the spleen, in the retroperitoneal area below the kidneys, along the aorta, or in the pelvis. Because the adrenal glands are situated close to the gonads during their early development, accessory tissue may also be present in the spermatic cord, attached to the testis in the scrotum, attached to the ovary, or in the broad ligament of the uterus. They are surrounded by areolar tissue, containing much fat and covered by a thin, fibrous capsule attached to the gland by many fibrous bands. The adrenal glands have their own fascial supports so they do not descend with the kidneys when these are displaced. The cut section demonstrates a golden cortical layer and a flattened mass of darker (reddish-brown) medullary tissue. The left adrenal gland is generally elongated or semilunar in shape and is a little larger than the right one. It is more centrally located, its medial border frequently overlapping the lateral border of the abdominal aorta. Its posterior surface is in close relationship to the diaphragm and to the splanchnic nerves. The upper twothirds of the gland lie behind the posterior peritoneal wall of the lesser sac. The lower third is in close relationship to the posterior surface of the body of the pancreas and to the splenic vessels. Arterial blood reaches the adrenal glands through a variable number of slender, short, twiglike arteries, encompassing the gland in an arterial circle (see Plate 3-5). On the left side, the left adrenal vein is situated inferomedially and empties directly into the left renal vein. Arterial and venous capillaries within the adrenal gland help to integrate the function of the cortex and medulla. Extra-adrenal chromaffin tissues lack these high levels of cortisol and produce norepinephrine almost exclusively. A midline incision may be used if the patient has a narrow costal angle or bilateral adrenal disease is present. The approach to the left adrenal gland is typically through the gastrocolic ligament into the lesser sac. The left adrenal is exposed by lifting the inferior surface of the pancreas upward, Gerota fascia is opened, and the upper pole of the kidney is retracted inferiorly. The approach to the right adrenal gland involves mobilizing the hepatic flexure of the colon inferiorly and retracting the right lobe of the liver upward. The patient is in the prone position and the incision is either curvilinear extending from the 10th rib (4 cm from the midvertebral line) to the iliac crest (8 cm from the midvertebral line) or a single straight incision over the 12th rib with a small vertical paravertebral upward extension. Laparoscopic Transabdominal Adrenalectomy Since its description in 1992, laparoscopic adrenalectomy has rapidly become the procedure of choice for unilateral adrenalectomy when the adrenal mass is smaller than 8 cm and there are no frank signs of malignancy. The postoperative recovery time and long-term morbidity associated with laparoscopic adrenalectomy are significantly reduced compared with open adrenalectomy. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the side to be operated facing upward. On the right side, the liver with the gallbladder is retracted upward, and the retroperitoneum is incised. Keys to Successful Adrenal Surgery the keys to successful adrenal surgery are appropriate patient selection, knowledge of anatomy, delicate tissue handling, meticulous hemostasis, and experience with the approach used. The sympathetic preganglionic fibers for these glands are the axons of cells located in the intermediolateral columns of the lowest two or three thoracic and highest one or two lumbar segments of the spinal cord. They emerge in the anterior rootlets of the corresponding spinal nerves; pass in the white rami communicantes to the homolateral sympathetic trunks; and leave them in the greater, lesser, and least thoracic and first lumbar splanchnic nerves, which run to the celiac, aorticorenal, and renal ganglia. Some fibers end in these ganglia, but most pass through them without relaying and enter numerous small nerves that run outward on each side from the celiac plexus to the adrenal glands. These nerves are joined by direct contributions from the terminal parts of the greater and lesser thoracic splanchnic nerves, and they communicate with the homolateral phrenic nerve and renal plexus. Parasympathetic fibers are conveyed to the celiac plexus in the celiac branch of the posterior vagal trunk, and some of these are involved with adrenal innervation and may relay in ganglia in or near the gland. On each side, the adrenal nerves form an adrenal plexus along the medial border of the adrenal gland. Filaments associated with occasional ganglion cells spread out over the gland to form a delicate subcapsular plexus, from which fascicles or solitary fibers penetrate the cortex to reach the medulla, apparently without supplying cortical cells en route, although they do supply cortical vessels. Most of the branches of the adrenal plexus, however, enter the gland through or near its hilum as compact bundles, some of which accompany the adrenal arteries. The preganglionic sympathetic fibers end directly around the medullary cells because these cells are derived from the sympathetic anlage and are the homologues of sympathetic ganglion cells. Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter in the ganglia, and the postganglionic fiber releases norepinephrine. The chromaffin cell of the adrenal medulla is a "postganglionic fiber equivalent," and its chemical transmitters are epinephrine and norepinephrine. At birth, in addition to a thin outer layer of permanent cortex, there is a thick band of fetal cortex, which soon involutes.

Order 10mg crestor with amex

The resulting increases in temperature cholesterol levels life insurance 20mg crestor sale, intracellular hydrogen ion concentration, and Pco2 shift the dissociation curve to the right. The resulting increase in affinity for oxygen enhances its uptake by hemoglobin in the pulmonary capillaries. This organic phosphate, an intermediate product of anaerobic glycolysis, decreases the affinity of hemoglobin for oxygen and promotes the increased release of oxygen that takes place in the peripheral tissues. This is a much larger fraction than for oxygen because of the much greater solubility of carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is also carried in the red blood cells bound to hemoglobin as carbamino-hemoglobin. It is possible to measure hydrogen ion concentration directly, the normal value in blood being 35 to 45 nm/L. Respiratory Disturbances Respiratory acidosis is seen with alveolar hypoventilation and is characterized by an elevated Pco2 and a low pH. It can also occur as a consequence of disorders of the brain or when diseases affect the respiratory neuromuscular apparatus. Persistent carbon dioxide retention and acidosis promote the renal retention of bicarbonate. Respiratory alkalosis results from alveolar hyperventilation, causing an excessive output of carbon dioxide that leads to hypocapnia and an elevated pH. In early stages of cardiopulmonary disorders, stimulation of pulmonary mechanoreceptors as well as hypoxemia can stimulate ventilation and induce respiratory alkalosis. Renal adjustments to chronic respiratory alkalosis involve the excretion of bicarbonate ions by the kidney. Within several days, the bicarbonate ion concentration decreases and, despite the persistence of hypocapnia, the pH is restored to virtually normal values. Whereas levels of nonvolatile acids are increased in diabetes, uremia, and shock, loss of bicarbonate occurs in chronic renal insufficiency and with diarrhea. The resultant increase in hydrogen ion concentration is a strong respiratory stimulant. The delicate alveolar-capillary boundary where gas exchange takes place can be injured by inhaled or bloodborne noxious agents. Among the tissue components of the lung, the type I or membranous pneumocyte, the predominant cell type lining the alveoli, is most susceptible to injury (see Plate 2-22). The organism defends itself against the harmful effects of oxidant injury by mobilization of antioxidants such as -tocopherol or by the conversion of lipid peroxides to hydroxy compounds, a reaction that is promoted by reduced glutathione. Increased oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants. They concluded that a vasoactive substance was removed during passage of the perfusate through the lung. The substance affecting the renal vasculature was later found to be serotonin, which was either removed or inactivated during its journey through the pulmonary circulation. The structure of the lung and its location within the circulatory system are eminently suited to fulfilling this role. The fate of serotonin in the lung is one example of the interaction between circulating vasoactive substances and the endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature. In animals, it also causes bronchoconstriction, but human airways show no response to this mediator. Serotonin produced in the gastrointestinal tract reaches the liver via the portal circulation. In the liver, it is converted by means of a reaction that involves monoamine oxidase to 5-hydroxyin-doleacetic acid, a freely diffusible and water-soluble substance that does not have any known pharmacologic actions. Serotonin in blood reaching the lung is effectively removed by uptake into pulmonary endothelial cells. Prolonged exposure of the endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature to excess serotonin leads to structural changes in the right side of the heart and large pulmonary vessels. Aldosterone promotes retention of sodium by kidney, thus correcting volume deficit and acting as "feedback" to decrease release of renin 2. Renin is a protease that acts on angiotensinogen (renin substrate), a globulin produced by the liver. Aldosterone is carried via the bloodstream to the kidneys, where it promotes the retention of sodium for correction of the original intravascular volume deficit. Renin produced by juxtaglomerular apparatus of kidney in response to stimuli such as volume depletion or hypotension Kidney 7. Impulses from respiratory centers descend in spinal cord to reach diaphragm via phrenic nerves and intercostal muscles via intercostal nerves to increase rate and amplitude of respiration 1. These receptors also increase afferent discharge in response to hypercapnia or acidosis. These respiratory centers integrate sensory input from chemical and neural receptors and provide neuronal drive to the respiratory muscles. However, the respiratory system is also under the voluntary control of the motor and premotor cortices. Our understanding of the control of respiration is a result of investigations involving both humans as well as animals. Neural Receptors (see Plate 2-26) Various neural receptors are present in the upper airways, tracheobronchial tree, lung, chest wall, and pulmonary vasculature. The two major types of receptors are: Slowly adapting pulmonary stretch receptors and muscle spindles Rapidly adapting irritant receptors, including C-fibers Both slowly and rapidly adapting receptors respond to changes in lung volume. In addition, irritant receptors are sensitive to chemicals and inhaled noxious agents. The C-fiber nerve endings are located in the epithelium of the airways and respond to the local milieu. When one or more of these receptors or fibers are stimulated, an afferent impulse is sent via the vagus nerve to the central respiratory centers. It is believed that input from these neural receptors contributes to the hyperventilation (as evident by hypocapnia) that develops in patients with respiratory disorders. Central Respiratory Centers (see Plate 2-26) the central respiratory centers are located in the medulla and in the brainstem. Both stimulatory and inhibitory afferent impulses are integrated within these centers. However, the premotor and motor cortexes can exert voluntary respiratory system control via projections in the corticospinal tracts that synapse with the muscles of respiration. Both feedforward and feedback mechanisms are thought to contribute to the hyperpneic response. The feedforward ventilatory stimulation originates in the higher locomotor centers and stimulates phrenic, intercostal, and lumbar respiratory motor neurons. Current evidence suggests that both feedforward and feedback effects are synergistic for regulating exercise hyperpnea. In healthy untrained individuals, the capacities for ventilation and alveolar-arterial oxygen transport are more than adequate at all exercise intensities. However, when highly trained individuals perform maximal exercise, mechanical limits of the lung. The respiratory alkalosis caused by the hyperventilatory response decreases the sensitivity of both peripheral and central chemoreceptors. In high-altitude natives, pulmonary hypertension and systemic hypotension are common but reversible features. The stability of this system can be affected by a number of abnormalities, including: Physical loss of mandated control elements Fluctuations in controller gain Unpredictable latency to restoration of the reference state O2 Respiratory response to hypoxemia is blunted or lost In persons born at and living for many years at high altitude Some physiologic alteration persists for some time after moving to sea level O2 In children with congenital cyanotic heart disease, similar phenomena occur and persist into later life. What ensues is an oscillatory rectifier, the magnitude and persistence of which relate to how much the signal from the original disturbance is amplified. As a result, there is tremendous variability in the patterns of breathing observed in healthy individuals.

Effective crestor 20mg

This form of crush injury occurs in association with vehicle crashes cholesterol levels as you age buy cheap crestor 5 mg line, industrial accidents, uncontrolled crowd conditions and trampling, and any type of trauma characterized by a heavy object falling onto the chest, such as an individual working under a car that slips off the jack or a child pinned under a garage door. There may be intense swelling of the face and neck, as well as petechial hemorrhages of the skin of the face and conjunctiva. It is postulated that deep inspiration and transient airway obstruction exaggerate the superior vena cava hypertension. Traumatic asphyxia can be fatal, but the prognosis for those surviving to reach the hospital is good. Interestingly, despite the alarming appearance, many patients have relatively few complaints. Ninety percent of patients who survive the first few hours after injury will recover, but survival rates vary depending on the prevalence and degree of associated injuries. Diaphragmatic injuries may be caused by penetrating or blunt trauma; the mechanism influences the site and extent of injury. With gunshot wounds, the chances of right versus left side are roughly equal, and the wound from most handguns is small, usually smaller than 1 cm. The left hemidiaphragm is injured two to three times more frequently than the right after blunt trauma. The difference is attributed to the protective effect of the liver that distributes a sudden increase in intraabdominal pressure more evenly across the right hemidiaphragm. Blunt diaphragm injuries are considerably larger than penetrating wounds and are usually larger than 5 cm in length and in many cases exceed 10 cm. Consequently, there is high risk for abdominal viscera to herniate into the thorax. The risk is higher on the left side because the liver provides a barrier on the right, and herniation increases with the extent of the diaphragmatic defect. On the other side, incarcerated stomach, colon, or small bowel may produce peritoneal signs. The most definitive diagnostic adjunct is laparoscopy or thoracoscopy, but multidetector computed tomography scanning and magnetic resonance imaging are becoming more accurate. In hemodynamically stable patients, laparoscopy may be used to evaluate the abdominal organs and, in the event of no hollow visceral injury, may suffice for definitive repair of the diaphragm. In the chronic phase with delayed visceral herniation, a thoracotomy is generally recommended to free the lung from adhesions and provide access to the diaphragm injury. The hyaline membranes are formed by coagulation of plasma proteins that have leaked onto the lung surface through damaged capillaries and epithelial cells. It is more common in white than black infants and nearly twice as common in boys as girls. Surfactant protein B deficiency results in lethal respiratory failure; it has an autosomal recessive inheritance. The capillaries are strikingly congested, and pulmonary edema and lymphatic distension may be present. Epithelial necrosis in the terminal bronchioles at sites underlying the hyaline membranes suggests that a reaction to injury has taken place. These changes are now rarely seen because prematurely born infants have usually received prophylactic surfactant (see below). Surfactant deficiency results in failure of stabilization of small airways at end-expiration with consequent reduction of functional residual capacity. Uneven distribution of inspired air and perfusion of nonventilated alveoli result in poor gas exchange characterized chiefly by hypoxemia. In some infants, recovery is slow, with infants remaining ventilator and oxygen dependent for weeks and even months. In many centers, this is administered within the first few minutes after birth (prophylactic surfactant). The results of other trials have demonstrated that it is better to give surfactant prophylactically rather than selectively. Others, however, have an associated respiratory acidosis and need more respiratory support. Numerous forms of mechanical ventilation are available, including positivepressure ventilation, patient-triggered ventilation, highfrequency jet ventilation, and high-frequency oscillation. Infants who survive the first week or so of illness may become respirator and oxygen dependent. At autopsy, the lungs are found to be heavy, hypercellular, and fibrotic, with squamous metaplasia of even the small airways. Because the cilia are gone, it is not surprising that secretions pool; either atelectasis or lobular emphysema is common. Histologically, the syndrome is identified by the classic finding of diffuse alveolar damage, but few patients undergo lung biopsy during the course of their clinical illness. In some patients, the inflammatory response is self-limited, and the alveolarcapillary membrane is able to be repaired. There is generally minimal interstitial inflammation, and if this is present in significant amounts, the histopathologic diagnosis should be reconsidered. In addition, where available, lung transplant should be recommended to qualified patients. A mixed obstructive-restrictive pattern is found on lung function testing, and arterial hypoxemia is common. The chest radiograph shows diffuse, fine reticular or nodular interstitial opacities, usually with normalappearing lung volumes. However, symptomatic and physiologic improvement occurs in only a minority of patients (28% and 11% of cases, respectively). The architecture of the lung is relatively preserved, and the dense fibrosis is approximately of the same age. Weight loss, fevers, arthralgias, and pleuritic chest pain are other common findings. At low magnification, the process typically seems to affect the lung diffusely and appears uniform from field to field. Corticosteroid therapy appears to be associated with modest clinical benefit but usually not with resolution of disease. In 50% of cases, the onset is heralded by a flulike respiratory illness that includes fever, malaise, fatigue, and cough. A leukocytosis without increase in eosinophils is seen in approximately half of patients. Pulmonary function is usually impaired with a restrictive defect being most common. Although the consolidation has a patchy distribution, the lesions involve predominantly the subpleural and peribronchial regions. Areas of patchy ground-glass attenuation are present as well Intraluminal buds of granulation tissue consisting of loose collagen-embedded fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are present in the alveolar ducts and spaces certain clinical syndromes. Foamy macrophages are commonly seen in the alveolar spaces, presumably secondary to the bronchiolar occlusion. Chest radiographs show bilateral symmetric alveolar opacities located centrally in middle and lower lung zones, sometimes resulting in a "bat wing" distribution. For asymptomatic patients with little or no physiologic impairment (despite extensive radiographic abnormalities), a period of observation is recommended. Repeated episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage with resultant blood-loss anemia and eventual respiratory failure characterize the illness. A structural defect in the alveolar capillaries may predispose individuals to the condition. Repeated hemorrhages result in hemosiderin-laden alveolar macrophages and the deposition of free iron in pulmonary tissue; the latter may result in the development of lung fibrosis. During acute bleeding episodes, crackles, wheezes, and rhonchi with dullness to percussion are noted over the involved lung areas. During acute hemorrhagic episodes, the chest radiograph exhibits patchy or diffuse alveoli-filling shadows.

Order crestor 5 mg without a prescription

In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer have allowed unprecedented access to gametes and the early developing embryo cholesterol in eggs new study buy crestor 10 mg. Changing patterns of sexual expression, new technologies, increased consumerism, and heightened cost pressures all affect the choices made in the search for fertility control. The remaining unplanned pregnancies occur as a result of either failure of the contraceptive method used or the improper or inconsistent use of the method. Although efficacy and an acceptable risk of side effects are important in the choice of contraceptive methods, these are often not the factors upon which the final choice is made. Motivation to use, or continuing to use, a contraceptive method is based on education, cultural background, cost, and individual needs, preferences, and prejudices. The impact of a method on spontaneity or the modes of sexual expression preferred by the patient and her partner may also be important considerations. Currently available contraceptive methods seek to prevent pregnancy by preventing the sperm and egg from uniting or by preventing implantation of the embryo that results from the fertilized egg. For example, hormonal contraceptives, including postcoital contraceptives, work primarily by preventing the development and release of the egg but, if ovulation occurs, may affect the likelihood of either the sperm and egg uniting or reducing the likelihood of implantation. Copper intrauterine devices, by contrast, work primarily through a toxic effect on sperm and egg; in the event of fertilization, however, the likelihood of implantation is decreased. Careful counseling about options (including abstinence), the risks of pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease, as well as the need for both contraception and disease protection must be provided. Compliance concerns are generally less in these patients, making use-oriented methods more acceptable and reliable. At this early stage, two types of cells can be distinguished; some proliferate more rapidly, forming a sphere that encloses the aggregate of more slowly dividing cells. While these changes take place, the ovum continues its passage into the uterine cavity, where it becomes implanted on the seventh or eighth day after ovulation. Various conditions may slow or obstruct the passage and cause nidation elsewhere, resulting in an ectopic pregnancy. If the zygote splits very early (first 2 days after fertilization), each cell may develop separately its own placenta (chorion) and amnion (dichorionic diamniotic twins), which occurs 18% to 36% of the time. The remaining decidua surrounding the blastocyst is called the decidua basalis, whereas the term decidua vera or parietalis designates the entire endometrium lining the uterus, except for the parts surrounding the blastocyst. From the ectoderm will derive the central nervous system, the epidermis, and certain skin appendages. The mesoderm will give rise to the epithelium of the urinary and genital systems, the linings of the serous cavities, the various supporting tissues of the body, the blood, and the cardiovascular system. Each villus consists of a mesodermic core covered by two layers of trophoblastic cells. The more distinct cells of the inner layer are designated cytotrophoblasts or Langherans cells. A high percentage (as high as 50% to 60%) of fertilized oocytes do not result in pregnancies completing the first trimester of gestation. Despite the dramatic changes that the conceptus undergoes in the first 14 weeks of gestation, many patients are unaware of their pregnancy or delay seeking prenatal care. During the first trimester of gestation, the developing embryo implants in the endometrium (except in the case of ectopic pregnancies), the placental attachment to the mother is created, and the major structures and organs of the body are formed. About the 12th week of gestation, the placenta takes over hormonal support for the pregnancy from the corpus luteum. Home urine pregnancy tests normally cannot detect a pregnancy until at least 12 to 15 days after fertilization. Morning sickness occurs in about 70% of all pregnant women and typically improves after the first trimester. Symptoms of fatigue and breast fullness may occur relatively early in the course of gestation, and abdominal distension begins later in this trimester. Brainstem activity has been detected as early as 54 days after conception, and the first measurable signs of brain electroencephalographic activity occur in the 12th week of gestation. If a genetic evaluation of the fetus is indicated, chorionic villus sampling may be performed between the 10th and 12th week of gestation or amniocentesis may be done between 15 and 20 weeks. Fetal waking and sleeping cycles become established and mimic those of the newborn, with the baby awake for about 6 hours a day. Fetal viability (ability to survive apart from the mother) begins about 24 weeks, though neurologically intact survival at this stage is unlikely. Toward the end of this trimester, maternal hemorrhoids and low back pain may make their appearance. The fetus is making insulin and urinating, with fetal urine being a significant component of amniotic fluid. If a genetic evaluation of the fetus is indicated, an amniocentesis may be performed between the 15th and 20th weeks of gestation. It is generally during the second trimester that ultrasonographic screening for appropriate gestational age, fetal growth, and major fetal malformations is performed. By the 29th week, the fetus has 300 bones, though eventual fusion of more than 90 of these fetal growth plates following birth will leave the adult total of 206. At the beginning of this trimester, in the male, the testes descend into the scrotum under the guidance of the gubernaculum, which in the female become the round ligaments supporting the fundus of the uterus. Maternal blood volume increases by almost twice and cardiac output reaches its maximum. Late in this trimester, changes in the cervix prepare for dilation and effacement during labor and delivery. It is also in the latter portion of this trimester that the number of oxytocin receptors on the uterine muscle cells increases markedly and there is an increase in the number of intercellular gap junctions. These micropores between cells provide a mechanism to facilitate the organized and effective coordinated contractions necessary for successful labor. Uterine contractions that have been present since conception become progressively stronger and more noticeable as the trimester progresses. These are the Braxton-Hicks contractions of late pregnancy and the contractions of labor and delivery. The growth also results in relocation of the maternal center of gravity, causing the mother to lean backwards to compensate. Planning and preparation for breastfeeding should be undertaken during this trimester. For selected patients, "kick counts" may be used to assess the overall health of the fetus. Trophoblastic cells have marked invasive capacities and grow into the walls of maternal blood vessels, establishing contact with the maternal bloodstream. In early pregnancy, trophoblastic cells frequently invade deep into the myometrium, but as pregnancy progresses, invasion is limited by profuse proliferation of decidual cells, which confine the trophoblastic invasion to the area just beneath the attachment of the growing placenta. In the recently implanted blastocyst, the rim of trophoblastic cells, with the underlying mesodermic stroma, constitutes the primitive chorion. At the same time, the amnion first appears as a small cavitation in the mass of proliferating ectodermal cells in the embryonic area. This cavity gradually enlarges and folds around the developing embryo, so that eventually the latter is suspended by a body stalk (the umbilical cord) in a closed bag of fluid (the amniotic sac). During the early stage of development of the amnion, another vesicle appears in the embryonic area and for a time is much larger than the amnion. In rare cases the chorionic villi, beneath the decidua capsularis, do not undergo atrophy but establish Decidua capsularis Decidua vera Uterine cavity Chorion laeve Chorionic villi (chorion frondosum) Amnion Fetus Body stalk (umbilical cord) Decidua basalis Decidua marginalis Amnion completely encircling the early fetus, which is attached only by the body stalk. Early fetal development and membrane formation in relation to the uterus as a whole (schematic). In this condition, called placenta membranacea, the entire chorion is covered with villi, and the thin placenta thus formed bleeds freely, does not separate spontaneously, and is difficult to remove manually during the third stage of labor. The chorionic villi contain no blood vessels during the first 2 weeks of gestation, and the embryo has not yet developed a circulatory system. The spiral arteries in the decidua become less convoluted and their diameter is increased. These changes are most marked in the decidual portion of the spiral arteries but extend into the myometrium as the pregnancy advances. The villi absorb nutrients and oxygen from the maternal blood in the intervillous space, and these materials are transported to the growing fetus through the umbilical vein and its villous and cotyledon tributaries. Waste products for excretion into the maternal blood are brought from the fetus through two umbilical arteries, which are continuations of the fetal hypogastric arteries. These vessels terminate in the rich capillary network of the chorionic villi, where they are in close contact with the maternal bloodstream. The villi are oxygenated directly from the maternal blood and exhibit infarction whenever the maternal circulation around them ceases.

Robbia (Madder). Crestor.

- Kidney stones, menstrual problems, urinary problems, and other uses.

- How does Madder work?

- Are there safety concerns?

- What is Madder?

- Dosing considerations for Madder.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96556

Purchase crestor 5 mg on line

Infant swimming in chlorinated pools and the risks of bronchiolitis cholesterol medication safe for liver crestor 5mg discount, asthma and allergy. Swimming pool attendance, asthma, allergies, and lung function in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohort. Competitive swimmers with allergic asthma show a mixed type of airway inflammation. Respiratory symptoms, bronchial responsiveness, and cellular characteristics of induced sputum in elite swimmers. Childhood asthma and environmental exposures at swimming pools: state of the science and research recommendations. High levels of airborne ultrafine and fine particulate matter in indoor ice arenas. Airway inflammation, bronchial hyperresponsiveness and asthma in elite ice hockey players. Emerging concepts in the evaluation of ventilatory limitation during exercise: the exercise tidal flow-volume loop. Several studies have shown that food allergic individuals who develop asthma are at higher risk for severe asthma. In addition, asthma in individuals with food allergy places those patients at higher risk for severe allergic reactions to food, such as anaphylaxis, particularly if the asthma is poorly controlled. Food allergy should be considered in children with acute, life-threatening asthma exacerbations with no identifiable triggers and in highly atopic children with severe persistent asthma resistant to medical management. Management of food allergy and asthma according to well-defined national guidelines is essential to establish good control of these conditions, particularly when they are concomitant. In patients with concurrent food allergy and asthma, education about heightened risks is an important step in treatment, and intramuscular epinephrine is the drug of choice in treatment of anaphylaxis. Taylor-Black, Dept of Pediatrics, Box 1198, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1 Gustave L. It is clear, however, that children with comorbid food allergy and asthma have increased morbidity. Children with both food allergies and asthma are at increased risk for severe anaphylaxis, including fatal and near-fatal anaphylaxis, particularly if the asthma is uncontrolled [1]. In this chapter, we will discuss the findings of recent studies which explore the relationship between food allergy and asthma, as well as review food-induced anaphylaxis and its relationship to asthma. In the community, there appears to be a strong perception that food allergy and asthma are linked, perhaps because they are well-known atopic conditions. This is reflected in the increasing literature investigating the relationship between food/diet and asthma [2]. In a survey of patients attending an asthma and allergy clinic, 73% believed that foods triggered their asthma symptoms [3]. There have been several studies which examine whether food allergy predisposes to asthma. For example, studies have shown that sensitisation to egg, one of the most common food allergens in childhood, is a risk factor for sensitisation to aeroallergens and asthma later in life [7, 8]. Sixtynine children with confirmed food allergies to egg and/or fish were followed until school-age. All of the children had developed tolerance to egg and 17% of those with fish allergy developed tolerance at follow-up. Moreover, there was no association between the severity of allergic reaction to foods and risk of developing asthma. In addition, wheezing is often a precursor to the development of asthma and the association between food sensitisation and viral-induced wheeze has been explored in a Finnish study [11]. Immunoglobulin (Ig)E antibodies for cod, milk, egg, peanut, soy and wheat were obtained in 247 hospitalised wheezing children aged 3 months to 16 years. Food allergen sensitisation was found to be associated with human rhinovirus-induced wheezing, although it was not associated with wheezing caused by other viruses [11]. The association between food allergy and asthma is further supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating a high rate of food allergies in asthmatic children. Evidence for this increased prevalence is particularly strong in those reporting current asthma and having had emergency department visits for asthma in the previous year. Evidence from several studies have shown that children with asthma and concurrent food allergies tend to have worse asthma morbidity than those with asthma alone. While these studies defined food allergies based only on serologic testing, a few studies have found associations between clinical food allergy and increased asthma morbidity. Another study specifically examined the role of peanut allergy with asthma and found similar results [15]. Having peanut allergy was associated with higher rates of hospitalisation and use of systemic corticosteroids compared to asthmatics without peanut allergy. A dose effect for the number and severity of food allergies with the likelihood of having a diagnosis of asthma has also been demonstrated [16]. Those who had severe allergic reactions to foods had higher rates of asthma, and those with milk, egg, and peanut allergies were independently associated with increased rates of asthma. Another study found that children with food allergy presented with asthma at an earlier age than those without a history of food allergy. However, there was no association between asymptomatic food sensitisation and asthma prevalence or severity [16]. The role of food allergy in the development of asthma has been investigated in several studies by focusing on objective measurements of lung dysfunction associated with asthma. Interestingly, respiratory symptoms were observed in only 26% of food allergic children during the oral food challenge, even in children with asthma [18]. This finding is concerning for ongoing eosinophilic airways inflammation in food allergic children, and may suggest a need for inhaled corticosteroid use in children with peanut allergy reported to have outgrown their asthma or children with untreated wheeze [24]. Although lower respiratory symptoms [25] and occupational asthma [26, 27] can be triggered by food allergic reactions, food allergy generally does not present with chronic or isolated respiratory symptoms [25]. In a study of 279 asthmatics with a history of food-induced wheezing, 60% had a positive double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge and, of these, 40% had wheezing as one of several symptoms [28]. In another large study with over 300 patients with both food allergy and atopic dermatitis, 27% of the positive double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges manifested with pulmonary symptoms as part of the allergic reaction, with only 17% of these having wheezing, and very few patients having isolated wheezing [29]. Finally, although respiratory symptoms may not always accompany food allergic reactions, a concurrent diagnosis of asthma appears to worsen the general prognosis for food allergy. Most importantly, asthma is a risk factor for fatal food-induced anaphylaxis [1] and will be discussed later. Asthma and food allergy in children: epidemiology There appears to be an increasing prevalence of both food allergies and asthma in the past few decades. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine the prevalence of asthma accurately due to the 61 S. Based on self-reports of asthma, the incidence more than doubled between 1980 and 1996 [32], and now, nearly one (9. The gold standard for food allergy diagnosis is a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge, which is labour intensive, time consuming and impractical in large-scale epidemiological studies. The majority of the available data is derived from surveys and measurement of specific IgE. Although these tools have various diagnostic limitations, studies employing these methods have reported consistent estimates of food allergy prevalence. In a recent study from a minority urban multi-ethnic birth cohort, both self-reported Black race and African ancestry were associated with food sensitisation and a high number (at least three) of food sensitisations [35]. Additionally, this study found that Black race, male sex and childhood age were risk factors for food allergy. This study also reported that peanut, milk and shellfish were the most common allergies, and found that multiple food allergies were reported for 2. The odds of food allergy were significantly higher among Asian and black children versus white children. Interestingly, a significant inverse relationship between prevalence and socioeconomic status was also found in this study [38]. Food-induced anaphylaxis and asthma Food-induced anaphylactic reactions are not uncommon and account for more than one-third of the anaphylactic reactions treated in emergency departments [41]. Peanut, tree nuts, fish or shellfish are the foods most often implicated in these reactions [41]. Another study of food-induced anaphylaxis found seven cases of fatal food anaphylaxis evaluated during a 16month period [43]. Common risk factors identified for these fatal and near-fatal reactions included asthma, failure to identify the responsible food allergen in the meal and previous allergic reactions to the incriminated food [44].

Order crestor 5mg

Vestigial remnants of the wolffian duct can also exist in fully developed females cholesterol ranges hdl ldl discount crestor 10 mg free shipping. Vestiges of the male prostate may appear as periurethral ducts in the female (see Plate 7-5). In addition, homologues of male Cowper glands are the major vestibular glands (Bartholin glands) in the female (see Plate 6-16). At this undifferentiated stage, the external genitalia consist of a genital tubercle above a urethral groove. In male development, the genital tubercle elongates, forming a long urethral groove. The distal portion of the groove terminates in a solid epithelial plate (urethral plate) that extends into the glans penis and later canalizes. In female intersex disorders, the growth of this septum is incomplete, thus leading to persistence of the urogenital sinus. Male and female external genitalia in the first trimester of development appear remarkably similar. The principal distinctions between them are the location and size of the vaginal diverticulum, the size of the phallus, and the degree of fusion of the urethral folds and the labioscrotal swellings. More important than the source of androgens, however, is the timing and amount of hormone. Pregnenolone is converted to progesterone, which by degradation of its side chain is converted to androstenedione and then to testosterone. Estriol, a product of estrone metabolism in the placenta during pregnancy, is the third major estrogenic hormone in the female but is the least potent biologically. About 5% of normal daily testosterone product is derived from the adrenal cortex, and the remainder is secreted by the testis into the systemic circulation. The remainder of testosterone (2%) exists in a free or unbound form, which is the active fraction. Circulating estrogens have a similar bioavailability profile and are also carried on plasma proteins, notably albumin. Similarly, the value of testosterone supplements in older men who have reached andropause (androgen deficiency with age) is even more controversial, as large, randomized, placebo controlled trials of sufficient duration to assess longterm clinical outcomes and events have not been undertaken. Further coordination is provided by hormone action at multiple sites and eliciting multiple responses. Importantly, gonadal function throughout life, similar to the adrenal cortex and thyroid, is under the control of the adenohypophysis (anterior lobe of the pituitary) and hypothalamus. Most peptide hormones induce the phosphorylation of various proteins that alter cell function. In contrast, steroid hormones are derived from cholesterol and are not stored in secretory granules; consequently, steroid secretion rates directly reflect production rates. In bone marrow, testosterone causes accelerated linear growth and closure of epiphyses. It helps the liver to produce serum proteins and influences the male external appearance, including body hair growth and other secondary characteristics. Termed the "hormone of pregnancy," progesterone supports endometrial development in early pregnancy, thickens the cervical mucus to prevent infection, decreases uterine contractility, and inhibits lactation during pregnancy. It is also necessary for the complete action of ovarian hormones on the fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, external genitalia, and mammary glands. On average, girls begin puberty about 1 to 2 years earlier than boys (average age 10. Girls attain adult height and reproductive maturity about 4 years after the first changes of puberty. In contrast, boys accelerate more slowly but continue to grow for about 6 years after the first visible pubertal changes. Although boys are on average 2 cm shorter than girls before puberty begins, adult men are 13 cm (5. The hormone that dominates female development during puberty is estradiol, an estrogen. Stage 3 takes another 6 to 12 months, when hairs are too numerous to count and appear on the pubic mound. Although occurring more frequently with age after menarche, ovulation is not inevitably linked to the menstrual cycle, and many girls with cycle irregularity several years from menarche will continue to have irregularity, anovulation, and possibly infertility. The proportion of fat in body composition also increases, especially in the breasts, hips, buttocks, thighs, upper arms, and pubis. Rising androgen levels change the fatty acid composition of perspiration, resulting in an adult body odor and increased oil (sebum) secretions from the skin. Pubic hair is often the second change of In males, testicular enlargement is the first physical sign of puberty and is termed gonadarche. Although 18 to 20 mL is the average adult testis size, there is also wide ethnic variation. The sequence of sperm production and the onset of fertility in males is not as well documented, largely because of the variable timing and onset of ejaculation. Sperm can be detected in the morning urine of most boys after the first year of puberty and potential fertility can reached as early as 13 years of age, but full fertility is not achieved until 14 to 16 years of age. Following the appearance of pubic hair, other body areas that respond to androgens develop heavier hair (androgenic hair) in the following sequence: axillary hair, perianal hair, upper lip hair, sideburn hair, periareolar hair, and facial beard. Under the influence of androgens, the voice box, or larynx, grows in both genders. Most of the voice change occurs in stages 3 to 4 of male puberty, around the time of peak growth. By the end of puberty, adult men have heavier bones and nearly twice as much skeletal muscle as females. The peak of the "strength spurt" is observed about 1 year after the peak growth rate. As with females, rising levels of androgens change the fatty acid composition of perspiration, resulting in adult body odor and acne. Other findings include anosmia and midline abnormalities such as cleft palate and small testes. Primary testis failure, causing an inadequate testosterone surge at puberty and exemplified by Klinefelter syndrome, may also produce a delay in the onset or sequence of pubertal events (Plate 1-7). This syndrome may present with delayed puberty, increased height, decreased intelligence, varicosities, obesity, diabetes, leukemia, increased likelihood of extragonadal germ cell tumors, and breast cancer (20-fold higher than normal males). In idiopathic form (50% of cases), puberty proceeds in a normal pattern but begins earlier and is compressed into a shorter time frame. Although affected males are tall for their age during early puberty, the premature closure of the epiphyses results in a markedly short stature in adulthood. Central causes of precocious puberty include brain tumors near the third ventricle, including astrocytoma, meningioma, or pinealoma, and are usually accompanied by diabetes insipidus and visual field defects. The nonclassic form is milder and usually develops in late childhood or early adulthood. In addition, large quantities of cortisol precursors are made that form the substrates for androgens. Excessive androgens contribute to the virilization and also downregulate pituitary gonadotropin secretion, so that the testes remain small and infantile despite other pubertal changes. The clinical signs of a virilizing adrenal adenoma or cortical carcinoma are similar to those induced by any other cause (Plate 1-8). Again, 17-ketosteroids are usually not suppressed with glucocorticoids in this condition, and the adrenal glands are normal on imaging. Because this syndrome only affects the second X chromosome, the syndrome is only present in females. Occurring in 1 of every 2500 girls, the syndrome presents with characteristic physical abnormalities, such as short stature, broad chest, low hairline, low-set ears, and webbed neck. Girls with Turner syndrome typically have gonadal dysfunction (nonworking ovaries) that results in amenorrhea and sterility.

Purchase crestor 10 mg with visa

A cholesterol levels europe order 10mg crestor with amex, the fundus of the gallbladder has been opened and a finger introduced into the gallbladder for palpation. The superficial part of the fundus and body of the gallbladder has been excised, leaving in place its attachment to the liver and the infundibulum. The remaining mucosa is removed by curettage and electrocoagulation, and a drain is placed near the infundibulum. Insufficient preoperative assessment of a complicated situation is another avoidable reason for intraoperative difficulties. Dangerous surgery arises from inadequate or imprecise observation of the technical principles of cholecystectomy, insufficient experience, inadequate incision and exposure, or inadequate assistance. Dangerous pathology includes chronic or acute inflammation, which results in obscured anatomy and increased vascularity in the region of the cholecystectomy triangle. Portal hypertension is associated with increased venous collateralization, which makes the dissection hemorrhagic and dangerous. Hemorrhage in the cholecystectomy triangle represents potential danger because attempts at hemostasis by placing clamps with obstructed and insufficient view may result in inadvertent clamping of the right or proper hepatic artery or of the bile duct. In this situation one should first attempt to control the hemorrhage by digital compression or by clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament. Grasping the bleeding vessel should be done with precision so as to limit the risks of including another structure in the ligature. Blind placement of clamps for hemostasis can result in lesions of the hepatic artery or bile duct. Hemorrhage should be controlled first by manual clamping of the hepatoduodenal ligament until a better view is obtained, making precise hemostasis possible. Even where local endoscopic, radiologic, or laparoscopic expertise coexists, there are still indications for open choledochotomy: 1. Patients with gallstones and concomitant jaundice or acute suppurative cholangitis who cannot be managed by endoscopic sphincterotomy 3. Operative cholangiography showing a small stone in the nondilated, distal, intrapancreatic bile duct, unsuspected by the surgeon. Although impacted stones at the ampulla may be broken down and removed by a supraduodenal approach, they probably should be removed by means of a transduodenal sphincteroplasty because it is less traumatic. Supraduodenal Choledochotomy and Exploration of the Common Bile Duct Exposure the liver is retracted superiorly and the hepatic flexure of the colon superiorly. The balloon is inflated, and the catheter is withdrawn until it impinges against the papilla. The second part of the duodenum and posterior surface of the head of the pancreas are palpated, and the balloon is identified. The balloon is deflated and gently withdrawn through the papilla; this is detected by a sudden easing of the pull on the catheter. The catheter is withdrawn and reinserted upward into each of the main hepatic ducts, and the procedure is repeated. A, the Fogarty catheter is attached to a syringe, and the balloon is inflated in the duodenum. C and D, the balloon is deflated and gently withdrawn until it slips through the papilla; the balloon is reinflated. B, Long forceps can be used to obstruct the common hepatic duct to prevent the stone Postexploratory Investigations Choledochoscopy is the established method to ensure that the duct system is normal. Modern instruments allow visualization of the major right and left hepatic ducts and intermediate hepatic ducts. T-Tube Cholangiography After insertion of a T-tube and closure of the choledochotomy, T-tube cholangiography may be used for postexploratory investigation. T-Tube Drainage the standard practice is to use a T-tube to allow spasm or edema of the sphincter to settle after the trauma of the exploration. Another important reason for the use of a T-tube is the detection and subsequent treatment of retained stones. The correct position of the T-tube is with the long limb emerging under the costal margin laterally. If T-tube cholangiography is normal, the tube is removed about 5 to 7 days after operation. If there is a residual stone on T-tube cholangiography, it is extracted via interventional radiology or endoscopic papillotomy. A postexploration T-tube cholangiogram identifies a residual stone in the intrahepatic bile ducts, missed during operative exploration of the bile duct. A, the T-tube is modified by shortening the limbs to prevent proximal obstruction and distal entry into the duodenum. B, A T-tube is modified by removing half the diameter to prevent obstruction and enable easy removal. The choledochotomy closure is begun above, with the T-tube emerging at the lower end of the repair. It should not be attempted in the presence of a duodenal diverticulum or where there is severe periampullary inflammation. Technique Sphincteroplasty consists of the incision of the common portion of the sphincter of Oddi with partial suture of the incision margin. The papilla usually is located at the junction of the lower third with the upper two thirds of the second portion of the duodenum. If this is not the case, digital palpation can be used by running the forefinger, introduced through the duodenotomy, across the medial duodenal wall. Traction now is applied to these sutures, and incision of the sphincter is extended for a further 6 to 7 mm, with sutures placed every 2 to 3 mm (all laterally) until the entire common tract of the sphincter of Oddi is incised. Sphincteroplasty is completed when the incision is 10 to 21 mm long and forceps can be introduced easily into the common bile duct to extract stones or other foreign bodies. Anatomy the anatomic details of the extrahepatic biliary tree and adjacent hepatic arterial and portal venous structures are discussed in detail in Chapter 1, but some features warrant emphasis. The important ductal anomalies are nearly all related to the manner of confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts and of the cystic duct with the common hepatic duct. The right hepatic duct has a short extrahepatic portion, but the left hepatic duct always has a much longer extrahepatic course. The duct traverses to the left, together with the left branch of the portal vein, within a peritoneal reflection of the gastrohepatic ligament on the undersurface of the quadrate lobe. The ligamentum teres in the lower edge of the falciform ligament traverses the umbilical fissure of the liver. Elements of the portal triad are distributed to the right and left liver on a segmental basis. The ligamentum teres marks the umbilical fissure and runs to join the umbilical portion of the left branch of the portal vein. Note particularly the distribution of the left portal triad in the umbilical fissure. Preparation of a segment of the gastrointestinal tract, usually a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum 3. Direct mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis between these two the anastomosis may be "stented" by a transanastomotic tube. In selected cases in which the anastomosis is technically difficult and stenosis is anticipated because of recurrent malignancy or benign stricture or to provide access for subsequent interventional radiologic techniques, the Roux-en-Y loop may be developed so as to make its blind end subcutaneous. The blind end of the jejunal loop is kept deliberately long and brought to the abdominal wall. The anastomosis is splinted with a transjejunal tube, which is brought through the blind end of the jejunum and through the abdominal wall. This tube tract can be used as an avenue for subsequent interventional radiologic or choledochoscopic maneuvers. Note the clips on the jejunum and at the subcutaneous termination to guide the radiologist. In this case, the loop is used to allow transtumoral intubation and subsequent radiotherapy. A tube may be passed transjejunally (1), transhepatically (2), or as a U-tube (3).