Buy 400 mg indinavir with mastercard

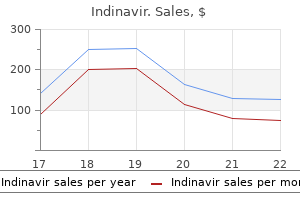

This is also the only region to contain dopaminergic neurons that project directly to the spinal cord aquapel glass treatment cheap indinavir 400mg amex. Whereas the normal functions of these neurons are not yet known, loss of this dopaminergic projection has been implicated in restless legs syndrome, a disorder in which patients experience abnormal sensations in their legs that prompt the urge to move their legs to quell the sensation. This path is a conduit for axons from diverse sources, including ascending and descending connections between the brain stem, the hypothalamus, and the cerebral hemisphere. Another pathway, the dorsal longitudinal fasclculus, contains ascending viscerosensory and descending hypothalamic fibers. This pathway is located within the gray matter along the wall of the third ventricle, in the midbrain periaqueductal gray matter and the gray matter in the floor of the fourth ventricle. Each mammillary body contains two nuclei: the prominent medial mammillary nucleus and the smaller lateral mammillary nucleus. Remarkably; the mammillary bodies establish virtually no intrahypothalamic connections. By contrast, most other hypothalamic nuclei have extensive intrahypothalamic connections. This shows that the function of the mammillary bodies is unlike that of the other hypothalamic nuclei. The mammillary bodies also have a descending projection to the midbrain and pons, the mammillotegmental tract. Whereas the mammillothalamic tract originates from the medial and lateral mammillary nuclei, the mammillotegmental tract originates only from the lateral nucleus. The outputs of the mammillary bodies are considered part of the limbic system and are discussed further in Chapter 16. Schematic drawing of Nissl-stained section through the posterior hypothalamus and mammillary bodies. There are also descending axons from the hypothalamus that are thought to travel through the dorsal longitudinal fasc:iculus en route to the spinal cord. Nudel In the Pons Are Important for Bladder Control the pons is an important site for bladder control. These neurons project to the parasympathetic bladder motor neurons to produce bladder wall contraction. In addition, axons from the pontine urination center synapse on interneurons that inhibit urethral sphincter motor neurons. Separate pontine neurons, located laterally and ventrally, that excite urethral sphincter motor neurons and produce sphincter contraction are implicated in circuitry to prevent urination. Axons In the bundle descend within the lateral brain stem, but they do not fonn a dlsaete tract. Adrenergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla project to the intermediolateral cell column for blood pressure control. Damage to the dorsolateral pons or medulla can produce Homer syndrome, a disturbance in which the functions of the sympathetic nervous system become impaired (see clinical case in this chapter; see also Box 15-1). The basic drcuit for urination control originates in the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus, where neurons project their axons to the pontine urination center. To enable urine to flow freely as bladder pressure Increases, there Is parallel Inhibition of the external sphincter motor neurons, via a connection with an Inhibitory lntemeuron In the Intermediate zone. Pregangllonlc Neurons Are Located In the Lateral Intermediate Zone ofthe Splnal Cord the descending autonomic fibers from the hypothalamus course in the lateral column of the spinal cord. Additional sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons are scattered medially in the intermediate zone. Because important control of the sympathetic nervous system is present in multiple divisions of the central nervous system, it is not surprising that damage at different levels can produce Horner syndrome (Box 15-1). The answer lies in identifying other neurological signs that may accompany Horner syndrome. The ascending postganglionic: sympathetic fibers ascend, in part, along the carotid artery. A Superior cervicalganglion B Deacending hypolhalamic fiberS in dorsolateral medulla Summary General Hypothalamic Anatomy the hypothalamus is a part of the diencephal. Orcult for Horner syndrome begins In the hypothalamus, where nudel control the autonomic nervous system. An Important nucleus for controlllng sympathetic functions Is the paraventr1cular nucleus. Lesion along the descending pathway In the brain stem and spinal cord an produce Homer syndrome. Additional hypothalamic and ext:rabypothalamic sites project to the median eminence and release gonadotropin-releasing hormones. Both parvocellular and magnocellular neurons colocalize additional neuroactive peptides. Autonomic Nervous System and Visceromotor Functions the autonomic nervous system has two anatomical components: the sympathetic division and the parasympathetic division. The parasympathetic division originates from the brain stem and the sacral spinal cord. Four parasympathetic nuclei in the brain stem contain preganglionic neurons (see Chapters 11and12): the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, the superior salivatory nucleus, the inferior salivatory nucleus, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. The major source of this projection is the autonomic division of the paraventricular nucleus. Orexin-containing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus are important for maintaining arousal. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus and its role in ingestive behavior and body weight regulation: lessons learned from lesioning studies. Mediobasal hypothalamic leucine sensing regulates food intake through activation of a hypothalamus-brainstem circuit. The integration of stress by the hypothalamus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex: balance between the autonomic nervous system and the neuroendocrine system. Neurochemical organization of the hypothalamic projection to the spinal cord in the rat. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Motor, cognitive, and affective areas of the cerebral cortex influence the adrenal medulla. A sex difference in the hypothalamic uncinate nucleus: relationship to gender identity. Developmental determinants of the independence and complexity of the enteric nervous system. The cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, consciousness and learning. The emotional motor system in relation to the supraspinal control of micturition and mating behavior. The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuronal projections from the mesencephalic raphe nuclear complex to the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the deep pineal gland of the golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus). The retinohypothalamic tract originates from a distinct subset of retinal ganglion cells. Medullary visceral reflex circuits: local afferents to nucleus tractus solitarii synthesize catecholamines and project to thoracic spinal cord. Light-induced c-Fos expression in suprachiasmatic nuclei neurons targeting the paraventricular nucleus of the hamster hypothalamus: phase dependence and immunochemical identification. The location of descending fibres to sympathetic neurons supplying the eye and sudomotor neurons supplying the head and neck.

Buy 400mg indinavir fast delivery

There have been multiple studies performed with anti-diabetic agents new medicine generic indinavir 400 mg without a prescription, including both biguanides and thiazolidinediones. It has been observed in large patient cohorts that cancers can be reduced in patients taking either class of drugs for a period of time. With regard to thiazolidinedione drugs, the principal agent under consideration is pioglitazone. There was a significant partial clinical response rate in over 70% of patients after 3 months. With regard to biguanides, metformin, a first-line drug commonly used to treat diabetes mellitus, also directly inhibits cell growth. Principal mechanisms for currently postulated chemoprevention drugs include forced differentiation and anti-inflammatory agents. With regard to agents that are hypothesized to force maturation, vitamin A and derivatives have been the most commonly used agents over the past 30 years. It was originally noted that vitamin A is necessary for the maintenance of normal health and maturation of mucosal tissues, particularly tissues in the oral cavity and the oropharynx. The initial landmark randomized controlled trial study for oral cancer prevention involved the use of 13-cis-retinoic acid. The clinical reductions in size of leukoplakia lesions were quite common but histologic improvement from high-grade to low-grade dysplasia or from low-grade dysplasia to normal were not nearly as common. Particularly, skin toxicities and hypertriglyceridemia were dose limiting toxicities. Over the years, doses were reduced to a point where they were no longer clinically effective. It is important to note that currently there is ongoing research to find safe retinoids that do not have dose limiting side effects. Dozens of retinoids have been synthesized, and a couple of compounds have made their way to early phase clinical trials. There has also been considerable interest in using retinoids as topical agents to avoid systemic toxicity. A number of publications point to the use of mucoadhesive patches with retinoids to treat oral leukoplakia. Our group and others have shown considerable pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the milieu of oral cavity carcinoma, preneoplastic lesions, and from cell lines and animals. Population studies and several meta-analyses have revealed that treatment with metformin is significantly associated with reduced cancer risk, suggesting that metformin might have chemoprevention efficacy in humans. There is significant interest in the use of raspberry derivatives with some successful human studies performed with demonstrated efficacy for topical preparations. Combined effect of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking in the risk of head and neck cancers: a re-analysis of case-control studies using bi-dimensional spline models. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis: relationship to risk factors associated with oral cancer. The potential role of in vivo optical coherence tomography for evaluating oral soft tissue: a systematic review. Mucoadhesive fenretinide patches for site-specific chemoprevention of oral cancer: enhancement of oral mucosal permeation of fenretinide by coincorporation of propylene glycol and menthol. Development and in vitro-in vivo evaluation of fenretinide-loaded oral mucoadhesive patches for site-specific chemoprevention of oral cancer. In oral cavity leukoplakia, we have very minimal ways to examine and stratify risks within the entire population of oral cavity leukoplakia patients. High-grade oral cavity leukoplakia (moderate, severe dysplasia, and carcinoma in situ) has a much higher chance of progressing to invasive cancer than hyperplasia or low grade dysplasia. Elevated levels of 1-hydroxypyrene and N-nitrosonornicotine in smokers with head and neck cancer: a matched control study. Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking and the risk of head and neck cancers: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] 426 52. Induction of differentiation and apoptosis by ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in non-small cell lung cancer. Inhibitory effects of troglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand, in rat tongue carcinogenesis initiated with 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide. Thiazolidinediones and the risk of lung, prostate, and colon cancer in patients with diabetes. Metformin prevents the development of oral squamous cell carcinomas from carcinogen-induced premalignant lesions. Metformin and cancer risk and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account biases and confounders. Metformin inhibits the inflammatory response associated with cellular transformation and cancer stem cell growth. Topical application of a mucoadhesive freeze-dried black raspberry gel induces clinical and histologic regression and reduces loss of heterozygosity events in premalignant oral intraepithelial lesions: results from a multicentered, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Topical application of a bioadhesive black raspberry gel modulates gene expression and reduces cyclooxygenase 2 protein in human premalignant oral lesions. Phase I clinical trial of curcumin, a chemopreventive agent, in patients with high-risk or pre-malignant lesions. Quick Access After you successfully register and activate your code, you can find your book and additional online media at medone. The disease produced profound impairments of cognition, including memory disturbances, and widespread degeneration of the cerebral cortex. Because the volume of the skull is fixed, as brain tissues decrease in volume, there is a corresponding increase in ventricular volume. A superior-to-inferior sequence of three images in the transverse plan (see insets is shown. Because of the extensive cortical atrophy, the cortical sulci are wider and filled with more cerebrospinal fluid. The hippocampal formation is key to consolidation of shortterm to long-term memory see Chapter 16). Its reduction in Alzheimer disease, together with degeneration of temporal lobe cortex, leaves a gaping hole in the temporal lobe. Although not visible on these images, a small nucleus on the inferior brain surface, the basal nucleus, is severely affected early in Alzheimer disease. This nucleus contains neurons that use the excitatory neurotransmitter acetylcholine. These neurons project widely throughout the cortex, and with their loss, many cortical neurons are deprived of excitatory input. This, together with the gross degeneration, helps to explain the cognitive impairments in the patient. The sizes of the midbrain (parts A2-A3 and B2-B3 and pons (parts A5 and B5 appear normal. The human nervous system carries out an enormous num1 ber of functions by means of many subdivisions. This task can be greatly simplified by approaching the study of the nervous system from the dual perspectives of its regional and functional anatomy. Regional neuroanatomy examines the spatial relations between brain structures within a portion of the nervous system. Regional neuroanatomy defines the major brain divisions as well as local, neighborhood relationships within the divisions. In contrast, functional neuroanatomy examines those parts of the nervous system that work together to accomplish a particular task, for example, visual perception. Functional systems are formed by specific neural connections within and between regions of the nervous system; connections that form complex neural circuits. A goal of functional neuroanatomy is to develop an understanding of the neural circuitry underlying behavior. By knowing regional anatomy together with the functions of particular brain structures, the clinician can determine the location of nervous system damage in a patient who has a particular neurological impairment and, in many cases, a psychiatric impairment. Combined knowledge of what structures do and where they are located is essential for a complete understanding of nervous system organization. The term neuroanatomy is therefore misleading because it implies that knowledge of structure is sufficient to master this discipline.

Purchase indinavir 400mg fast delivery

In the monkey treatment 20 nail dystrophy purchase indinavir on line, only about 40% of the dentate nucleus is devoted to motor system connections. This leaves an intriguingly large portion of the nucleus for nonmotor connections and functions. Considering the increased complexity of the human brain, the nonmotor functions of the cerebellum-and the interplay between these functions and motor behavior-will very likely be an important direction for clinical and basic studies in the future. In turn, the cortical area connects, via a synapse in the pontine nuclei, to hand controlling centers in the cerebellum. We will see a similar predominantly closed loop organization for the basal ganglia (Chapter 14). Additional projections also arise from association cortex in the parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes and from parts of the limbic cortical areas (which play important roles in emotions; see Chapter 16). This amplifies what was discussed earlier, that the nonmotor functions of the cerebellum are likely to be very important. Location of the superior cerebellar peduncle and associated axons from the cerebellum to the th<1lamus pale red sh<1ding) in relation to the red nucleus and ventrolater<1I nucleus of the thalamus. The topogniphk organlmtlon of the cortlcopontlne projection at the level of the basis peduncull. The cortlcopontlne projection originates from most areas ohhe cerebral cortex, whereas the cortlcosplnal projection originates only from the l)ft! Part B shows schematically the locations of the descending projections In the basis peduncull from the various cortical areas. The evolutlon of prefrontal Inputs to the cortlco-pontlne system: diffusion Imaging evidence from Maaque monkeys and humans. The climbing fibers make monosynaptic connections with the Purkinje neurons; the mossy fibers synapse on granule neurons, which in turn synapse on Purkinje neurons via their parallel fibers. All projections from the spinocerebellum to other parts of the brain course through the superior cerebellar peduncle. The dentate nucleus also projects, via the thalamus, to the prefrontal and parietal association cortex to mediate nonmotor functions. All projections from the cerebrocerebellum to other parts of the brain course through the superior cerebellar peduncle. All projections from the vestibulocerebellum to other parts of the brain course through the inferior cerebellar peduncle. Nonmotor Functions of the Cerebellum Portions of the posterior lobe of the cerebellum serve nonmotor functions. Although not as well-understood, cerebellar damage can produce impairments in cognition and emotions. The cerebellum and cognitive function: 25 years of insight from anatomy and neuroimaging. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. The cerebellar microcircuit as an adaptive filter: experimental and computational evidence. Somatotopic alignment between climbing fiber input and nuclear output of the cat intermediate cerebellum. The inferior parietal lobule is the target of output from the superior colliculus, hippocampus, and cerebellum. A review of differences between basal ganglia and cerebellar control of movements as revealed by functional imaging studies. Neuropsychological consequences of cerebellar tumour resection in children: cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in a paediatric population. Anatomical organization of the spinocerebellar system in the cat, as studied by retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase. Anatomical evidence for cerebellar and basal ganglia involvement in higher cognitive function. The origin ofthalamic inputs to the arcuate premotor and supplementary motor areas. From movement to thought: anatomic substrates of the cerebellar contribution to cognitive processing. Course of the fiber pathways to pons from parasensory association areas in the rhesus monkey. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Projections of individual Purkinje neurons of identified zones in the ventral nodulus to the vestibular and cerebellar nuclei in the rabbit. From lateral to medial, the anterior and posterior lobes of the cerebellar cortex connect with the deep nuclei in the following order: A. Which of the following is the principal synaptic target of Purkinje neurons of the nodulus Which of the following best explains the laterality of ataxia (ie, side of body on which ataxia presents) during reaching Contralateral, because cerebellar output is ipsilateral and the descending motor pathways decussate B. Bilateral, because the cerebellar output is ipsilateral and the descending pathways are bilateral 5. Which of the following circuits traces the connection, via the cerebellum, from the right posterior parietal cortex to the spinal cord A person has olivopontocerebellar atrophy, with extensive degeneration of the inferior olivary nucleus and the pontine nuclei, as well as parts of the cerebellum. Between mossy fibers and granule neurons; between climbing fibers and Purkinje neurons C. Between climbing fibers and basket neurons; between mossy fibers and Purkinje neurons D. Distal limb control by interrupting cerebellar connections to rubrospinal neurons B. The cerebellum is thought to be a site of dylfunction in several neuropsychiatric diseases, such as schizophrenia and autism. Which of the following statements best describes how information from frontal and temporal lobe areas involved in cognition and emotion can be influenced by cerebellar processing! Frontotemporal association areas must transmit information first to premotor and motor areas, which project to the pontine nuclei and then the cerebellum. Frontotemporal association areas must transmit information frrst to the posterior parietal association cortex, which projects to the pontine nuclei and then the cerebellum. Frontotemporal association areas transmit information directly to the pontine nuclei and then the cerebellum. Frontotemporal association areas project directly to the cerebellar cortex as mossy fibers. The movements primarily tnvolved flexton and rotation of the proxtmal parts crf the limbs. Despite the dlencephalic location of the lesion, the neurologist called to examine the patient suspects basal ganglia Involvement. Answer the following questions based on your reading of this chapter and relevant sections from other chapters. How is the diencephalon linked with basal ganglia motor functions and how might that lead to a motor impairment Knowledge of the Intrinsic Cin:uiby of the Basal Ganglia Helps to Explain Hypokinetic and Hyperkinetic Motor Signs Box 14-2. Key neurological signs and corresponding damaged brain structures Subthalamic nudeus drcuitry the subthalamic nucleus is a diencephalic structure that is part of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia. From there, information is directed to the motor thalamus, and then the motor cortex, which controls movements contralaterally, via the corticospinal tract.

Order 400 mg indinavir with mastercard

Immediate treatment with broadspectrum antibiotics should be considered (after taking appropriate samples for culture) in febrile patients or those with a suspected infection symptoms 9 dpo purchase indinavir 400 mg free shipping. The presence of a large mediastinal mass is a clinical emergency as it can cause superior vena cava syndrome and/or tracheal obstruction very quickly. These patients should not be sedated or anaesthetized and-if possible-biopsy of the mass should be avoided: diagnostic samples can often be obtained from pleural or pericardial effusions, which are commonly present. If the patient is very symptomatic, then it may be necessary to commence steroid therapy prior to establishing a diagnosis. The development of tumour lysis syndrome needs to be avoided; hence, it is important to monitor electrolytes and kidney function while giving appropriate hydration and allopurinol. This step dramatically improved overall survival in the 1960s and 1970s, but unfortunately came at a cost of significant long-term toxicity including cognitive impairment, decreased growth, endocrinopathies, and secondary brain tumours. Consequently, in children, the need for allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in first remission has diminished. This is in contrast to adult patients where allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is still advocated in first remission. Both of these compounds achieve good responses and measurable residual disease negativity. In contrast, children who have a late first relapse have a high remission rate after salvage therapy and an overall survival of 60%. Patients who relapse early have a 50 to 70% chance of regaining remission and have an overall survival of 20 to 30%. Most patients in second complete remission will undergo myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation to consolidate their remission. Autologous T cells from the patient are genetically modified to kill leukaemic blasts and then reinfused into the patient. The initial response rates are very good and durability of remissions are very promising but relapses with novel immunological relapse mechanisms have been observed. Role of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation In children, allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is usually not recommended in first remission but is of significant benefit in patients who attain a second complete remission after relapse. The role of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with high-risk disease. In adults, the poor outcome after relapse has changed the strategy over the last few years and patients regarded to be at high risk for relapse. Reduced-intensity conditioning is used in adults older than 40 years, whereas a myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is preferred in children and younger adults. The antileukaemic benefit of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is attributed to two factors: high-dose chemotherapy with or without total-body irradiation conditioning regimens and the graft-versus-leukaemia effect of donor cells against recipient malignant cells. Two antibodies have been shown to be superior to standard salvage chemotherapy in large phase 3 studies. However, the majority of elderly patients will receive specifically designed less intense chemotherapy protocols, which have a chance of cure but at the same time are not too toxic; thus, the treatment can be administered in outpatient settings with reduced hospitalization in order to provide improved quality of life. There are five key risk factors predicting treatment response: age, sex, immunogenetic subtype, initial disease burden, and response to therapy. Age is one of the main risk factors and, with the exception of infants (<1 year), risk increases with age. Traditionally, males have had a greater risk of relapse compared to females, largely due to the risk of testicular relapse. However, modern protocols which sometimes prolong the length of maintenance therapy for boys now rarely report major differences in outcome by sex. Immunophenotype and acquired genetic abnormalities, which are tightly related, are key predictors of outcome (Table 22. Traditionally, this has been measured by morphological examination of early bone marrow samples to assess the proportion of blasts remaining after treatment has been initiated or by clearance of blasts in the peripheral blood after 1 week of steroid treatment. Alternatively, flow cytometry can be used to track the presence and abundance of a leukaemia-associated aberrant immunophenotypic profile. These children will have an excellent chance of a cure and many protocols have reported overall survival rates of greater than 90% for this subgroup. Infants, patients with Down syndrome, and elderly patients have a higher risk of dying from toxic complications. Short-term toxic effects the commonest of these is febrile neutropenia due to bacterial and fungal infections, which can be life-threatening as patients have significant treatment-induced immunosuppression. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be commenced immediately as per hospital policy. Common noninfective short-term toxic effects include nausea and vomiting, hair loss (intermittent), and transfusion reactions. Long-term toxic effects Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy is rare, but if it occurs it can cause severe cardiac failure, often decades after the original treatment. As with all chemotherapy regimens, the risk of secondary malignancies is increased and is in low single figures. A few patients will become infertile; this occurrence is significantly higher if patients undergo allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and reaches nearly 100% if patients receive total-body irradiation as part of the conditioning protocol. There is also an increased risk of premature ovarian failure in women who received chemotherapy in childhood. Treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults: a broader range of options, improved outcomes, and more therapeutic dilemmas. Novel monoclonal antibody-based treatment strategies in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The clinical relevance of chromosomal and genomic abnormalities in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Treatment and monitoring of Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia patients: recent advances and remaining challenges. Minimal residual disease diagnostics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: need for sensitive, fast, and standardized technologies. Those with more advanced- stage disease require combination chemotherapy, with radiotherapy to sites of initial bulk disease. Since many patients have a good outcome, it is essential to minimize the long-term sequelae of treatment, such as pulmonary fibrosis and the development of secondary cancers. Introduction Epidemiology and risk factors Unlike non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the incidence of Hodgkin lymphoma has been stable over the period 1950 to 2000, with about three new cases per 100 000 population/year in Western countries. Approximately 9000 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States of America and 1800 in the United Kingdom. This dual peak has led some to propose that Hodgkin lymphoma actually represents two illnesses, with the earlier peak being related to an infectious aetiology and the latter representing a true malignancy, but there is little evidence to support this hypothesis. Incidence is about 3 per 100 000 per year in Western countries with a bimodal age distribution meaning that it is one of the commoner lymphomas of young people. Most cases are highly responsive to combination chemotherapy, with many patients being cured of their disease. Presentation and diagnosis Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma may present with lymphadenopathy, a mediastinal (or other) mass, and systemic symptoms including weight loss, fever, and night sweats (B- symptoms). Additional histological subtypes have been defined, with the most clinically significant being lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (with its differing clinical profile and management). Patients in Western countries who develop Hodgkin lymphoma in young adulthood usually have the nodular sclerosis subtype. Hodgkin lymphoma is approximately 100 times more likely in an identical twin of an infected patient. Although these might be taken as evidence of a genetic or infectious aetiology, the cause of Hodgkin lymphoma remains unknown. Pathobiology of lymphoma Increased understanding of the biology of the immune system has allowed the improved classification of lymphomas, and provided new prognostic information and new potential targets for therapy. Although the genetics of lymphomas are complicated, they too are beginning to be unravelled. Information gleaned from all these studies is likely to further change both the classification and therapy of the lymphomas. Then, early in the 20th century, Reed and Sternberg independently described the characteristic giant cells that now bear their name.

Diseases

- Ophthalmoplegia mental retardation lingua scrotalis

- Hypercalcemia, familial benign

- Pili torti nerve deafness

- Antisynthetase syndrome

- Fibrous dysplasia of bone

- 3 hydroxyisobutyric aciduria, rare (NIH)

- Aagenaes syndrome

Cheap indinavir online

Myelln-stalnecl transvene section through the caudal ponsand deep cerebellar nuclei medicine 79 order generic indinavir pills. Remarkably; each Purkinje neuron receives input from only a single climbing fiber. Individual climbing fibers branch to contact no more than about 10 Purkinje neurons. Mossy fibers first synapse on granule neurons-the only excitatory intemeurons in the cerebellum. How then can neurons in the deep cerebellar nuclei and vestibular nuclei transmit control signals to the motor pathways when they are only inhibited by Purkinje neuron Also, intrinsic cell membrane properties, such as high resting depolarizing ionic currents, help to maintain high levels of activity in these neurons. This continuously high level of neural activity is then reduced, or"sculpted," by the inhibitory actions of the Purkinje neurons. Similarly, for the vestibular nuclei, direct excitatory inputs from vestibular afferents and membrane properties help to maintain a high background level of activity. Because its synapse is located on the cell body, the basket neuron is very effective in inhibiting the Purkinje neuron. The action of these inhibitory interneurons is that Purkinje neurons will exert less inhibition on neurons in the deep nuclei and vestibular nuclei. Synaptic glomeruli ensure specificity of connections because this entire synaptic complex is contained within a glial capsule, formed by a subclass of astrocyte. An inventory of the synaptic action of the interneurons ofthe cerebellar cortex demonstrates that all but the granule neuron are inhibitory (Table 13-1). Beneath the stained neuron are stained synapses of a basket neuron, which Is Inhibitory. That a:mn may synapse on hundreds of Purkinje neurons that are stacked along the folium. The efficacy of parallel flber input onto a given Purkinje neuron is increased immediately after Purldnje neuron activation by a climbing flber. To reach the vestibular nuclei, Purkinje neuron axons of the vestibulocerebellwu travel through the inferior cerebellar peduncle. The cerebellum is thought to have a modular functional organization established, in part, by the projections ofclimbing tibers. Recall that the globose and emboliform nuclei collectively are termed the interposed nuclei. The efferent projections of the deep nuclei course through the inferior and superior cerebellar peduncles. The fastigial, interposed, and dentate nuclei have differential projections to motor control centers that reflect their functions in maintaining balance, controlling limb movement, and planning movement, respectively. The major targets of the output of the fastigial nucleus are the vestibular nuclei and the reticular formation, two components of the medial descending pathways that control balance and posture. The fastigial nucleus also influences the motor cortex, via the thalamus, and the ventral corticospinal tract. The major targets of the interposed nuclei are, via the thalamus, the motor cortex, and the magnocellular division of the red nucleus, where the rubrospinal tract originates. The major targets of the dentate nucleus are, also via the thalamus, areas of cortex involved in motor planning. Collectively, the projections from the deep cerebellar nuclei to the thalamus are termed the cerebellothalamic tract. The ventrolateral nucleus is the portion of the motor thalamus that receives mostly cerebellar input and, in turn, transmits this information primarily to the motor areas of the frontal lobe. The ventrolateral nucleus is separate from the thalamic somatic sensory nucleus, the ventral posterior lateral nucleus. One clue that makes identification a bit easier is the presence of the thalamic fasdculus. This band of myelinated fibers contains axons of the cerebellothalamic tract as well as axons of the basal ganglia projection to the thalamus (see Chapter 14). The ventrolateral nucleus is large and has many component divisions that have distinctive connections, primarily with the frontal lobe motor areas but also with the parietal lobe, which integrates sensory information for guiding movement. The interposed and dentate nuclei project to the part of the ventrolateral nucleus that relays information mostly to the primary motor cortex (area 4) and the premotor cortex (lateral area 6). In addition, the dentate nucleus projects to other parts of the ventrolateral nucleus that, in turn, project to the posterior parietal association cortex. The thalamic terminations of the dentate nucleus interdigitate with but do not overlay the terminations from the interposed nuclei. Routing through the thalamus, in the medial dorsal nucleus and other integrative nuclei, the projections target several regions within the prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex. As described earlier, whereas cerebellar damage in humans produces characteristic motor signs damage of the posterior cerebellar lobe can result in cognitive and affective changes. Additionally, the subthalamlc nucleus receives dense glutamaterglc Inputs from the motor cortex, primarily on the lpsllateral side. Whereas the cortical-basal ganglia circuitry ls lpsllateral, It exerts Its movement control Influence on the contralateral side because the cortlcosplnal tract ls predomtnantty crossed. Hemlballlsm, the condition resulting from subthalamlc nucleus lesion, is thus thought to be produced by disinhibition; it is a release phenomenon. It is not known why this is reflected in the violent proximal movements, so much a signature of subthalamic nucleus damage. The largest portion of the subthalamlc nucleus Is devoted to limb and trunk motor functions. In addition, smaller regions of the nucleus are more important for eye movement control, emotiona~ and cognitive functions. These regions are parts of the ocular motor, limbic, and cognitive loops ofthe basal ganglia. The basal ganglia are a collection of suhcortkal nuclei that I have captured the fascination of clinicians and scientists for well over a century because of the remarkable range of behavioral dysfunction associated with basal ganglia disease. Movement control deficits are among the key signs, ranging from the paucity and slowing of movement in Parkinson disease and the writhing m~ments ofHuntington disease to the bizarre ties of Tourette syndrome and distorted postures of dystonia. Unmistakingly, these clinical findings indicate that one important set of basal ganglia functions is regulating our motor actions. How do the basal ganglia fit into an overall view of the organization of the motor systems Unlike the motor cortex and several brain stem nuclei, which have direct connections with the spinal cord and motor neurons, the basal ganglia influence movements by acting on the descending pathways; this is similar to the cerebellwn. In addition to producing movement control deficits, basal ganglia disease can also impair intellectual capacity and affect, pointing to important roles in cognition and emotion. Dementia is an early disabling consequence of Huntington disease and can be present in patients with advanced stages of Parkinson disease. The basal ganglia play important roles in aspects of drug addiction and psychiatric disease. Although the basal ganglia continue to be among the least understood of all brain structures, their mysteries are now yielding to modem neurobiological techniques for elucidating neurochemistry and connections. For example, the basal ganglia contain virtually all of the major neuroactive agents that have been discovered in the central nervous system. Although the reason for this biochemical diversity remains elusive, such knowledge can be used to treat some fonns of basal ganglia disease. Knowledge about connections of the basal ganglia with the rest of the brain has led to a major revision of the traditional views of basal ganglia organization and function. Discoveries about basal ganglia circuitry and pathways have even led to therapeutic neurosurgical and neurophysiological procedures. This is a form of electrical neuromodulation that can be used to improve many of the disabling signs of basal ganglia disease. This article first considers the constituents of the basal ganglia and their three-dimensional shapes, partly from a developmental context. Next, their functional organization is surveyed, emphasizing the distinctive roles of the basal ganglia in movement control, cognition, and emotions. Organization and Development of the Basal Ganglia Separate Components of the Basal Ganglia Process Incoming Information and Mediate the Output the many components of the basal ganglia are best learned, in a general way, from the outset; then their functional and clinical anatomy can be mastered.

Generic 400mg indinavir otc

B Comment: Whereas the lateral superior olivary nucleus is important for localizing high-frequency sounds medications hydroxyzine discount 400 mg indinavir mastercard, this does not imply that it is where high-frequency sounds are selectively processed for perception. Indeed, there is a parallel path for all frequencies through the dorsal cochlear nucleus, which does not synapse in the lateral superior olivary nucleus. By contrast, when hair cells of the base of the cochlea have degenerated all transductive machinery for high-frequency sounds is lost. The medial lemniscus and the pyramid are supplied by direct branches of the vertebral artery. D Comment: the superior olivary nucleus contributes a small number of axons to the trapezoid body. B Comment: Neurons of the nucleus of the trapezoid body synapse with the lateral, not medial, superior olivary nucleus. This is part of the mechanism for localizing high-frequency Answers to Study Questions 475 sounds. The medial superior olivary nucleus is part of the circuitry for localizing low-frequency sounds. D Comment: Whereas afferent and efferent are often used interchangeably for sensory and motor, this is not true. Afferent means to bring information-whether sensory or motor in function-to a structure, whereas efferent means to bring information away from that structure. The territories supplied by the middle cerebral and basilar arteries also contain pathways or nuclei for both limb and trunk control. A Comment: the rubrospinal tract is a lateral path and thus descends laterally in the spinal cord. A Comment: In the motor cortex, the foot representation is supplied by the anterior cerebral artery. B Comment: the thalamic gustatory nucleus is the parvocellular division of the ventral posterior medial nucleus. Whereas the medial dorsal nucleus transmits taste information to the orbitofrontal cortex for integrating tastes and smells, it does not receive direct input from the ascending taste pathway. B Comment: the axons of primary olfactory neurons are able to regenerate; they are thought to be the only example of maintained capacity for axon regeneration in the adult mammalian brain. These axons are vulnerable to being transected (termed axotomy) by shearing forces during head trauma. C Comment: Unlike the spinal cord, where the motor nuclei are located ventral to sensory nuclei, it is different in the caudal brain stem. This is because as the fourth ventricle develops, it displaces the sensory nuclei laterally. In the midbrain, the only cranial nerve sensory nucleus, the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus, is located dorsal to the oculomotor nucleus, a dorsoventral organization like the spinal cord. Here in the midbrain, development of the narrow cerebral aqueduct does not displace the sensory nuclei. A Comment: Each olfactory receptor gene is expressed in one, or at most only a few, glomeruli. C Comment: the orbitofrontal cortex receives olfactory information from the piriform cortex, either directly or relayed via the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus. B Comment: Corticobulbar axons are commonly located in the genu of the internal capsule and corticospinal axons to the cervical spinal cord descend in the adjoining posterior limb. However, corticobulbar axons may be located in the most anterior portion of the posterior limb in some individuals. When this occurs, the corticospinal axons to the cervical spinal cord descend in the adjoining, but more posterior, portion of the posterior limb. A Comment: Facial motor neurons migrate from the ventricular surface ventrally, and possibly caudally, during development. Failure to migrate (in this fictitious condition) would result in retaining a position close to the ventricular floor, thus dorsal to the normal location. D Comment: the patient has a highly selective lesion because the impairment is restricted to the left arm. White matter lesions in the brain stem and spinal cord are unlikely to produce a single limb motor impairment because axons from all body parts intermingle within very small regions. Among the choices, only the precentral gyrus has a clear somatotopic organization. Moreover, occlusion of a small cortical branch of the middle cerebral artery could selectively damage the arm area of primary motor cortex, in the precentral gyrus. B Comment: Nucleus ambiguus has a rostrocaudal organization; motor neurons rostrally innervate pharyngeal muscles and caudally, laryngeal muscles. Blood pressure regulation is more the function of the solitary nucleus and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. D Comment: the tentorium separates the cerebellum from the overlying occipital and temporal lobes. Loss of ipsilateral facial pain is due to the damage to the trigeminal spinal tract, as well as the nucleus. This is mediated by the main trigeminal sensory nucleus, which is located in the pons. The principal input paths to the cerebellum, the dorsal and cuneocerebellar tracts, are ipsilateral. A Comment: Routing information through the pontine nuclei adds one additional decussation to the cerebellar control circuit Since the double crossing of the cerebellar output results in ipsilateral control we see that the cortico-pontocerebellar circuit restores the typical decussated control by the cortex. B Comment: the posterior spinal artery supplies the dorsolateral medulla, but caudal to the vestibular nuclei. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery supplies more rostral portions of the vestibular complex. B Comment: this condition would primarily produce loss of climbing fibers from the inferior olivary nucleus and mossy fibers from the pontine nuclei. B Comment: Despite its name, the lateral vestibulospinal tract is a medial pathway. A Comment: the contribution of the superior oblique muscle, which is innervated by the trochlear nucleus, to downward gaze is greater when looking at the nose, hence greater vertical diplopia. Intortion-the other mechanical action of the superior oblique muscle-is weakened, hence double vision when you tilt your head sideways, termed tortional diplopia. Finally, horizontal diplopia is produced by a palsy involving control of the lateral or medial rectus muscles. A Comment: the magnocellular division of the red nucleus is the recipient of cerebellar output from the interposed nuclei; rubrospinal neurons, which contribute to distal limb control, originate from this division. C Comment: Virtually all cortical regions-motor, premotor, and association areas-project to the pontine nuclei, which provide mossy fiber inputs to the cerebellar cortex (more the cortex than the dentate nucleus). This provides both a route for cortical areas important in cognition and emotion to influence movement, via the cerebellum, as well as contributing to the nonmotor functions of the cerebellum. D Comment: the left abducens nucleus is spared, or else the left eye would not be abducted. Comment: Dots correspond, from left (lateral) to right (medial): Insular cortex (sensory representations of pain, visceral sensations, and taste), claustrum (connects with cerebral cortex; may play role in consciousness), putamen (motor functions), external segment of the globus pallidus (part of indirect path; receives striatal input and projects to subthalamic nucleus), internal segment of the globus pallidus (direct path; basal ganglia output to thalamus and brain stem), posterior limb of the internal capsule (ascending thalamocortical axons; Answers to Study Questions 477 descending cortical projections). B Comment: these are signs of loss of sympathetic control of cranial structures on the left side. They can be produced by damage to the left: hypothalamus, descending hypothalamic projection, spinal cord, superior cervical ganglion, or sympathetic fibers in the neck. For example, ifthere is also ataxia, the lesion is likely in the dorsolateral medulla, or if there is limb paralysis, it is in the spinal cord. Comment: the lenticular fasciculus contains axons from the internal segment of the globus pallidus, not the substantial nigra pars reticulata. D Comment: Cerebral degenerative disorders generally result in loss of neurons without concomitant replacement with more glia, or glial scaring. Because the cranial cavity is of a fixed volume, this is accompanied by an increase in the nearby ventricle/aqueduct. C Comment: the posterior insular cortex is the primary cortical area for aspects of pain, visceral sensation, and vestibular function. D Comment: the parahippocampal gyrus is formally not part of the hippocampal formation. A Comment: the basolateral amygdala receives higher-order sensory information and processes this information for emotions.

Purchase 400mg indinavir with amex

The areas are organized in strips from primary cortex caudally treatment of bronchitis purchase 400mg indinavir mastercard, to higher-order areas rostrally. The areas are largely organized in a concentric scheme, with the primary area peripheral and the higher-order area central. The areas are largely organized in a concentric scheme, with the primary area central and the higher-order area peripheral. Using this approach, which of the following best describes the arcuate fasciculus Nucleus Relays Gustatory lnfonnation tD the Insular Cortex and Operailum the Olfactory System: Smell the Olfactory Projection to the Cerebral Cortex Does Nat Relay Through the Thalamus Regional Anatomy of the OlfactorySystem the Primary Olfactory Neurons Are Locatl! Diplopia presented as an inability to adduct the right eye on horizontal gaze to the left. On examination, taste was probed carefully by applying solutions of different qualities (salty, sweet, acidic, bitter and umami to the tongue. The results indicated a loss of all tested qualities of taste on the right side of the tongue. A taste researcher in the Otolaryngology Department was contacted, and the patient was subsequently examined using an electronic device to examine taste thresholds. The lesion In A corresponds to the dorsal tegmentum, where many tracts are located. You should be able to answer the following questions based on your reading of the chapter, earlier readings, Inspection of the Images, and consideration ofthe neurologkal signs. What are the major tracts within the lesioned/ demyellnated region and what are the general functions of these tracts How might demyelination produce an impairment in the function in the key tract for taste Key neurological signs and corresponding damaged brain structures Peripheral versus central lesions and the distribution oftaste loss Although uncommon, the patient has unilateral taste loss. Damage to a single nerve likely would result in partial taste loss, such as only on the anterior two thirds ofthe tongue with damage toa branch ofthe facial nerve. Critical brain stem gustatory structures the three nerves supplying taste buds converge upon the rostral solitary nucleus. The projection from the solitary nucleus ascends In the central tegmental tract, and tennlnates In the parvocellular division of the lpsllateral ventral posterior medlal nucleus of the thalamus. The pontlne lesion Is also likely to damage the parabrachtal nucleus, which could contribute to the Impairment. However, we learned In Chapter 6 that the parabrachlal nucleus ls more Important for visceral sensations. Further, other studies In the human reveal taste loss with small vascular lesions that are more selective to the central tegmental tract, demonstrating, at least, the Importance of the tract Rmtrnees Shlkama Y, Kato T, Nagaoka U, et al. Compared with those of the other sensory systems, the neural systems for processing chemical stimuli are remarkably different. For example, both taste and smell have ipsilateral projections from the peripheral receptive sheet to the cerebral cortex, whereas those of the other sensory systems are either contralateral or bilateral. Moreover, the primary cortical areas for taste and smell are within limbic system regions, where emotions and their associated behaviors are formed. Information from the other sensory modalities reaches the limbic system only after additional processing stages. Smells and tastes have a particular knack for evocative recall of our dearest memories. The gustatory and olfactory systems work jointly in perceiving chemicals in the oral and nasal cavities, a more essential collaboration than that which occurs between the other sensory modalities. For example, even though the gustatory system is concerned with the primary taste sensations-such as sweet or sour-the perception of richer and more complex flavors such as those present in wine or chocolate is dependent on a properly functioning sense of smell. Chewing and swallowing cause chemicals to be released from food that waft into the nasal cavity from the orapharynx, where they stimulate the olfactory system. Damage to the olfactory system, as a result of head trauma- or even the common cold, which temporarily impairs conduction of airborne molecules in the nasal passages-can dull the perception of flavor even though basic taste sensations are preserved. Although taste and smell work together and share similarities in their neural substrates, the anatomical organization of these systems is sufficiently different to be considered separately. T the Ascending Gustatory Pathway Projects to the lpsilateral Insular Cortex Taste receptor cells are clustered in the taste buds, located on the tongue and at various intraoral sites. Chemicals from food, termed tastants, either bind to surface membrane receptors or pass directly through membrane channels, depending on the particular chemical, to activate taste cells. These afferent fibers have a pseudounipolar morphology, similar to that of the dorsal root ganglion neurons. In contrast to the nerves of the skin and mucous membranes, where generally the terminal portion of the afferent fiber is sensitive to stimulus energy, taste receptor cells are separate from the primary afferent fibers. For taste, the role of the primary afferent fiber is to receive information from particular classes of taste receptor cells and to transmit this sensory information to the central nervous system, encoded as action potentials. For touch, the role of the primary afferent fiber is both to transduce stimulus energy into action potentials and to transmit this information to the central nervous system. Recall that the caudal solitary nucleus is a viscerosensory nucleus, critically involved in regulating body functions and transmitting information to the cortex for perception ofvisceral information as well as the emotional and behavioral aspects of visceral sensations. This pathway is thought to mediate the discriminative aspects of taste, which enable us to distinguish one quality from another. The insular gustatory cortex projects to several brain structures for further processing of taste stimuli. In addition, these cortical areas may be important for the behavioral and affective significance of tastes, such as the pleasure experienced with a fine meal or the dissatisfaction after one poorly prepared. A component of the processing of painful stimuli also involves the limbic system cortex, and pain in humans is not without emotional significance. Although taste and visceral afferent information (see Chapter 6) are distinct modalities and have separate central pathways, the two modalities interact. Another name for this behavior is bait shyness, referring to a method used by ranchers to discourage predators the Gustatory System: Taste There are classically four taste qualities-sweet, sour, bitter, and salty- and there are corresponding taste receptor cells for each of these modalities. A fifth quality has been proposed, termed savory, which is best associated with a meaty broth because a fifth class of taste receptor cell has been identified, umami (Japanese, flavor). Rather, the system is exquisitely organized to identify nutrients or harmful agents in what we ingest, in relation to particular physiological processes: sweet and savory are key to maintaining proper energy stores, salty for electrolyte balance, bitter and sour for maintaining pH, and bitter also for avoiding toxins. As discussed in Chapter 6, the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves also provide much of the afferent innervation of the gut, cardiovascular system, and lungs. This visceral afferent innervation provides the central nervous system with information about the internal state of the body. In this teclmique, ranchers contaminate livestock meat with an emetic, such as lithium chloride, which cause. After eating the bait, the predator develops an aversion for the contaminated meat and will not attack the livestock. People can experience a phenomenon related to conditioned taste aversion, in which they develop an intense aversion to food they ate before becoming nauseated and vomiting. Experimental studies in rats have shown that such interactions between the gustatory and viscerosensory systems, leading to conditioned taste aversion, may occur in the insular cortex. Taste receptor cells are short lived; they are regenerated approximately every 10 days. In addition to the taste recep- tor cells, taste buds contain two additional types of cells: bual cells, which are stem cells that differentiate to become receptor Regional Anatomy of the Gustatory System Branches of the Facial, Glossopharyngea~ and Yagus Nerves Innervate Different Parts ofthe Oral cavity Taste receptor cells are epithelial cells that transduce soluble chemical stimuli within the oral cavity into neural signals. Taste receptor cells have a synaptic contact with the distal processes of primary afferent fibers. A single afferent fiber terminal branches many times, both within a single taste bud and between different taste buds, so that it forms synapses with many taste cells. However, each sensory fiber will contact taste receptor cells that are responsive to a single taste modality. Taste buds (A) consist of taste receptor cells, supporting cells, and baSil cells.

Generic 400mg indinavir free shipping

Investigations for source(s) of bleeding the presence of iron deficiency anaemia demands a convincing explanation and a robust causal diagnosis: while malabsorption may be neglected medicine zyrtec generic indinavir 400mg line, occult haemorrhage is usually the most important to identify. The gastrointestinal system is the most frequent source of bleeding but can present a laborious challenge for diagnostic pursuit. Patients over the age of 60 years should be evaluated promptly, with upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy carried out as soon as reasonably possible. Iron deficiency anaemia in premenopausal women is often due to menorrhagia, dietary deficiency, hiatal hernia, or a combination of these factors, but endoscopy should not be neglected in men and women under 60 years in the presence of features such as weight loss or change in bowel habit. With patients in whom the cause of the iron deficiency is not apparent, intensive studies may be needed to confirm the presence and identify the source of gastrointestinal bleeding, including detection of occult blood in several consecutive samples of stool. Sophisticated endoscopic and radiographic studies of the gastrointestinal tract and serological studies for the presence of coeliac disease may be required, and occasionally there is a need to quantify the amount of blood loss daily in the faeces or during menstrual flow by using radiolabelled chromium red cell studies. In difficult cases, percutaneous visceral angiography of the coeliac and mesenteric arteries has proved useful for detecting sites of active gastrointestinal bleeding, due, for example, to angiodysplasia that are beyond the reach of conventional endoscopic procedures. In those patients who are actively bleeding, such a procedure can identify local sites of blood loss greater than 0. The recent introductions of fibreoptic double-balloon enteroscopy and wireless capsule endoscopy offer powerful, largely noninvasive means to examine the entire small-intestinal mucosa extensively for the presence of bleeding lesions. Other diagnostic tests include searching for endomysial (transglutaminase) antibodies, with confirmatory duodenojejunal biopsy to detect coeliac disease. Examination of the urine and sometimes sputum may be required to detect occult iron loss in exfoliated macrophages or proximal tubular cells, respectively, where intrapulmonary haemorrhage or renal iron loss from glomeruli is suspected. Sometimes extensive diagnostic procedures fail to identify the cause of iron deficiency when occult gastrointestinal bleeding is responsible. Under these circumstances it is sometimes appropriate Investigation of iron deficiency the identification of iron deficiency anaemia must be regarded as an illness description rather than a satisfactory diagnosis for any patient in its own right: management should always include a serious attempt to determine its root cause. All too often, mild oesophagitis or gastritis reported at endoscopy placates the incurious investigator when the underlying cause is bleeding from a coincidental source such as a cryptic gastrointestinal cancer for which a diligent search is often required. Malabsorption of iron as a result of, for example, coeliac disease, or chronic urinary loss of iron consequent upon intravascular haemolysis, are also important causes that are frequently not even considered until late into the illness. History A full evaluation of the patient with iron deficiency should include a detailed and systematic dietary history, including the consumption of drugs, such as aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents which may be responsible for gastrointestinal bleeding. Enquiry should be made to quantify the extent of menstrual loss, if the bleeding has been ascribed, as is often the case, to menorrhagia in women of reproductive age. Patients with malabsorption of iron often have accompanying nutritional deficiencies; coeliac disease has several well-known associations with autoimmune disorders such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and is most common but not at all exclusive to patients with Irish ancestry. Examination Clinical examination should extend from detailed enquiry about previous gastrointestinal disease or surgery to an examination for visceral enlargement, abdominal lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, masses, and other features suggestive of intra-abdominal pathology 22. The patient with recurrent chronic iron deficiency anaemia often presents a formidable challenge. First and foremost, an unequivocal diagnosis of iron deficiency is needed, and-so far as possible-blood loss, even from cryptic sources, should be excluded. While losses of iron through bleeding are frequently responsible, iron deficiency due to malabsorption of iron and even urinary losses as a result of chronic compensated intravascular haemolysis may need to be considered. Expert examination of the blood film with a reticulocyte count and review of present and past measures of iron status, as well as dietary review and other measures of nutritional status, are fundamental. There is a need to capture the past travel and surgical history, as well as a comprehensive list of prescribed and other drugs. Experienced physicians may need to seek interdisciplinary expertise in radiology, nuclear medicine, and surgery before prematurely abandoning the search for the causal lesion. Management of iron deficiency General aspects As a general rule, iron should only be recommended as a treatment for iron deficiency where that diagnosis is established beyond reasonable doubt: the presence of other causes of anaemia. Many microbes require iron and there is more than a hypothetical risk of infection if iron is given unnecessarily. Treatment of causes of anaemia, including bleeding, is clearly a critical aspect of the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Bleeding lesions in the gastrointestinal tract may require specific treatment; coeliac disease should be treated with a gluten-free diet. Occasionally, patients with a chronic bleeding disorder for which surgery is not effective, such as hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, may require long-term iron supplementation at doses less than that required to treat the acute iron deficiency state. In such circumstances, periodic monitoring is required to ensure that the level of iron replacement is adequate to meet the demands of the bone marrow for de novo haem synthesis and that iron overload is not occurring. It should be recognized that relief of iron deficiency will improve many symptoms suffered by a patient even though they may suffer from an incurable underlying disease. Treatment with iron should continue until iron stores are replenished: there is no excuse for inadequate therapy, especially in those patients who are likely to suffer recurrent bleeding. Particular attention is needed for iron-deficient patients who have had episodes of acute bleeding treated by blood transfusion and who at the time of therapy are not anaemic. These patients require appropriate iron replacement to replenish iron stores for their long-term restitution of health. Because iron therapy leads to a reduction in the avidity of the transport system of the intestine for iron, it should be continued for several months after the anaemia has been corrected to re-establish appropriate iron stores, ideally as reflected by a serum ferritin determination within the normal range. Iron should be replaced not only to restore the normal haemoglobin concentration but to replenish body iron stores. It is necessary to replace iron depleted in somatic tissues such as the muscles, where it is an essential component of mitochondrial cytochromes and other proteins critical for optimal aerobic metabolism. Occasionally, a therapeutic trial of oral iron for a defined period is justified to verify a suspected diagnosis of iron deficiency anaemia. The effects of therapeutic iron supplementation should be monitored: a reticulocyte response is normally observed in peripheral blood, peaking 7 to 10 days after initiating treatment, and with a significant increase in blood haemoglobin concentration apparent within 2 to 4 weeks. If there is no evidence of continued blood loss, the haemoglobin concentration should come within the healthy reference range within 2 months. Failure to meet these expectations suggests either that the anaemia is not caused by iron deficiency, or that there is continued depression of bone marrow function, or that there is persistent blood loss-for which further investigation is needed. Malabsorption of dietary iron is rarely severe enough to compromise the haematological response to pharmacological supplementation and an adequate response to oral iron does not preclude the existence of impaired assimilation of physiologically available iron in the small intestine. Oral delivery of iron Iron salts are best administered by mouth unless there are overwhelming reasons for using the parenteral route-parenteral preparations of iron are associated with a greatly increased risk of toxicity. Oral ferrous salts are better absorbed than ferric salts, but in practice show little difference among preparations in terms of rate of repair of anaemia at a given dosage of elemental iron. It is usual to treat iron deficiency anaemia with preparations of oral iron that contain 100 to 200mg of elemental iron daily. Some patients are unable to tolerate such a dose of iron because of constipation, diarrhoea, or abdominal pain and flatulence; the presence of tarry, black stools with a sulphurous odour further impair acceptability and the required persistence with therapy. Under these circumstances, the dose of iron may be reduced and this, rather than a change of iron salt preparation, usually improves tolerability. The frequency of unwanted effects with ferrous sulphate is generally similar to that of other iron salts when comparable quantities of elemental iron are ingested. Replenishment of iron has a slow effect on the epithelial changes of iron deficiency: the atrophic glossitis may take several months to improve as iron stores are replenished. In contrast, the behavioural manifestations, for example, pica syndromes, often respond to iron therapy within a few days. Slow-release oral preparations of iron are available, which the manufacturers often claim release sufficient iron over a 24-h period for optimal haematological responses after once daily dosages. However, these preparations are likely to distribute the iron beyond the upper jejunum and thereby bypass those regions of the intestine in which iron absorption is most avid. Compound preparations of iron including B vitamins and folic acid are available, but there is little justification for prescribing these except for prophylactic use in pregnancy (see following sections).