10mg prasugrel for sale

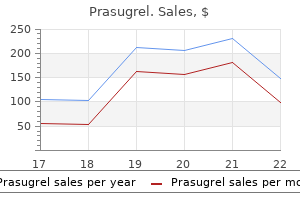

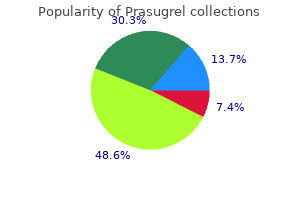

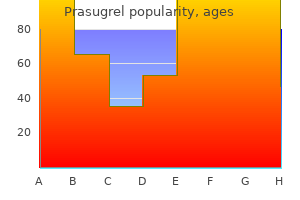

As the synovial inflammation decreases medications in spanish purchase 10 mg prasugrel mastercard, there is an increase in fibrous tissue leading to a chronic stage that lasts for 3 to 5 years and has a less predictable course. Further investigation is necessary to better elucidate the etiology of idiopathic chondrolysis of the hip and improve the understanding of its natural history. Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis of a girl 13 years and 2 months of age, with idiopathic chondrolysis of the right hip. This radiograph reveals complete loss of the joint space with resultant acetabuli protrusio. Treatment recommendations have changed over the years and are still in evolution as more information is collected concerning the natural history of idiopathic chondrolysis of the hip. The technetium bone scan of the pelvis of a patient with idiopathic chondrolysis demonstrating a diffuse uptake of the isotope by both sides of the affected left hip. This is accomplished in most patients with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, aggressive physical therapy, periodic traction with bed rest, and prolonged protected weight bearing for the involved hip. There is a recent report on the use of etanercept in one case of an adolescent boy with a stiff, painful hip that failed treatment with traction, physical therapy, naproxen, and methotrexate (166) Etanercept is a biologic response modifier (fusion protein consisting of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of tumor necrosis factoralpha and the constant portion of human IgG1) that binds and inactivates tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a proinflammatory cytokine. This novel therapeutic approach offered symptomatic relief and radiographic improvement and may provide an effective treatment strategy for these difficult cases. Surgical releases of unresolved contractures including aggressive subtotal capsulectomy and tendon releases can be used, but more recent long-term follow-up indicates that the improvements achieved may deteriorate with time (165). Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs of a girl 13 years and 3 months of age, with idiopathic chondrolysis of the right hip. A: A radiograph made at the time of diagnosis demonstrates significant loss of joint space and osteopenia at the involved hip. B: A radiograph of the same patient 18 months after diagnosis demonstrates partial regeneration of the joint space width in the affected hip. Coxa vara infantum, hip growth disturbances, etiopathogenesis, and long-term results of treatment. Femur remodelled during growth after osteomyelitis causing coxa vara and shaft necrosis. The fate of the capital femoral physis and acetabular development in developmental coxa vara. Congenital coxa vara: computed tomographic analysis of femoral retroversion and the triangular metaphyseal fragment. The histological characteristics of congenital coxa vara: a case report of a five year old boy. Growth disturbances of the proximal end of the femur: an animal experimental study with tetracycline. Contribution of the epiphyses of the greater trochanter to the growth of the femur. The treatment of developmental coxa vara by abduction subtrochanteric and intertrochanteric femoral osteotomy with special reference to the role of adductor tenotomy. Coxa vara infantum, growth disorders of the hip, their etiopathogenesis and remote results of treatment. Pelvic floor anatomy in classic bladder exstrophy using 3-dimensional computerized tomography: initial insights. Exstrophy of the bladder: long-term results of bilateral posterior iliac osteotomies and two-stage anatomic repair. Iliac osteotomy: a model to compare the options in bladder and cloacal exstrophy reconstruction. The snapping hip: clinical and imaging findings in transient subluxation of the iliopsoas tendon. Normal radiographic values for cartilage thickness and physeal angle in the pediatric hip. Discussion on the differential diagnosis of nontuberculous coxitis in children and adolescents. Lack of association of transient synovitis of the hip joint with human parvovirus B19 infection in children. Transient synovitis: lack of serologic evidence for acute parvovirus B-19 or human herpesvirus-6 infection. The validity of radiographic assessment of childhood transient synovitis of the hip. Evaluation of hip disorders by radiography, radionuclide scanning and magnetic resonance imaging. The irritable hip: immediate ultrasound guided aspiration and prevention of hospital admission. Septic arthritis versus transient synovitis of the hip: the value of screening laboratory tests. Significance of laboratory and radiologic findings for differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip. Seven year follow up of children presenting to the accident and emergency department with irritable hip. A randomized clinical trial: should the child with transient synovitis of the hip be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? Idiopathic chondrolysis of the hip: management by subtotal capsulectomy and aggressive rehabilitation. The balance between opposing muscle groups is also a determinant of foot position and may introduce a significant, dynamic component to the rotational profile. Age is another important variable because version, soft-tissue pliability, and muscle coordination change as the child matures (1). Differences in appearance related to foot position during walking or running are most often just that, differences, not pathologic conditions. It results from the summation of several factors that include version of the bones, capsular pliability, and muscle control (1, 3͵). The static examination should be performed on a firm examining table, with the child in comfortable, loose clothing such as shorts or a diaper. Rotation is best assessed with the child in the prone position, keeping the pelvis flat and level on the examination table (3͵). Flexion of the knee to 90 degrees allows the leg to be used like a goniometer relative to the thigh. The arc of rotation may be more generous if measured with the hip flexed as in a sitting position (5). Rotation of the leg laterally or medially is used to assess the degree of available hip rotation. When there is a greater degree of internal or medial rotation (outward movement of the leg in the prone position) than external or lateral rotation, a toed-in gait is more likely to be observed. Similarly, if there is greater external rotation than internal rotation, the gait pattern is usually toed-out. It is defined as the angular difference between the axis of the foot and the line of progression. C: Medial hip rotation is the maximum angular difference between the vertical and the axis of the tibia. It should correctly be called antetorsion because hip rotation is the combined effect of version of the femur, joint mobility, and muscle function (1, 3, 5). True femoral torsion can be accurately assessed by noting the position of the leg while palpating the greater trochanter laterally. Static medial hip rotation averages 40 degrees in infants, but can range from 10 to 60 degrees. It increases slightly by the age of 10 years and then decreases gradually in adulthood. Lateral hip rotation is greater than medial rotation in infants; it averages 65 degrees (range, 45 to 90 degrees), compared to children over the age of 10 years who average 40 degrees (range, 20 to 55 degrees) (1ͳ, 5, 9, 10). A: the method of recording the degree measurements for each element of the profile is depicted. This simple chart includes the vital information necessary to establish the diagnosis and to document severity. In each figure, the age is listed on the abscissa on a logarithmic scale and the degrees are shown on the ordinate scale.

Diseases

- Intestinal spirochetosis

- Thumb absence hypoplastic halluces

- Duplication of leg mirror foot

- Apert like polydactyly syndrome

- Rodini Richieri Costa syndrome

- Growth retardation alopecia pseudoanodontia optic

- Xeroderma pigmentosum

- Dyserythropoietic anemia, congenital

- Multiple sclerosis

Buy prasugrel canada

However medicine 657 purchase prasugrel pills in toronto, it should be stated that the diagnosis of clubfoot in the newborn can and should be based solely on clinical findings. The intended role of radiographs in the assessment of foot deformities is to demonstrate the relationships between bones. This is accomplished by first drawing the axis of each bone, and herein lies the limitation of this imaging modality. There is little ossification of the bones in the normal newborn foot, and there is a delay in ossification in the clubfoot (126). The ossific nucleus of the talus is not centrally located in the cartilaginous anlage (127, 128). The ossific nucleus of the talus is between the head and neck and may be spherical in shape for the first several weeks of life. Ossification of the navicular does not begin until age 3 to 4 years in children with clubfoot and even then is eccentric. These factors make it unrealistic to consider radiographs of the newborn and infant clubfoot as objective data. Despite these limitations, there might be a role for radiographs to confirm correction of the clubfoot deformities or to help identify the site(s) of residual deformity in the child who is several months old and has been undergoing serial manipulation and casting. In the latter situation, the information can be helpful for surgical planning, particularly if one ascribes to a carte surgery (118, 119, 130). The talocalcaneal and talusΦirst metatarsal angles are measured on both views (10). The axis of the talus and calcaneus normally diverge from each other and the axis of the talus and the first metatarsal normally form a nearly straight line on both views. The axis of the talus normally aligns almost perpendicular to the tibia and the calcaneus dorsiflexes above a right angle with the tibia. A second point at which radiographs may be helpful is intraoperatively to confirm the adequacy of correction of the deformities. The low dose radiation and convenience of minifluoroscopy make that technology desirable. The third indication for radiographs could be at some substantial time after surgery to confirm maintenance of deformity correction. Alternatively, the third point at which radiographs are obtained is when recurrence or other secondary deformities are identified. In response to the limitations of radiographs, ultrasound techniques are evolving for the assessment of the infant clubfoot during nonoperative and operative treatment (133ͱ37). The talus (small straight arrow) and calcaneus (large straight arrow) are parallel, rather than divergent. The cuboid ossification center (curved arrow) is medially aligned on the end of the calcaneus, rather than in the normal straight alignment. The talus and calcaneus are somewhat parallel to each other and plantar-flexed in relation to the tibia. Arthrography, computerized tomography (138), and magnetic resonance imaging (127, 139, 140) may have a role in research or in the evaluation of postsurgical deformities, but do not have a role in the routine assessment of the idiopathic clubfoot. The intrauterine diagnosis of clubfoot has become increasingly frequent with the routine use of fetal ultrasonography during pregnancy. This has implications for the orthopaedist, who is being consulted by prospective parents regarding the diagnosis, possible relationship to syndromes, treatment options, and prognosis. It appears that the earliest that a clubfoot can be diagnosed by ultrasound with accuracy is 12 weeks of gestational age. With sequential studies, there is an increased ability to visualize the deformity, relating either to the progressive development of a clubfoot deformity or perhaps the accuracy with which it can be seen. In 86% of cases, the deformity is identified by 23 weeks of gestational age, but still others are recognized up to 33 weeks. Three-dimensional ultrasound may provide a more accurate diagnosis than standard ultrasound studies (142). In studies of large populations using routine in utero ultrasound (143), the recognition of clubfoot deformity varies from 0. The false-positive rate for in utero diagnosis of clubfoot using ultrasound varies from 30% to 40%, depending on the series and the criteria (144ͱ47). A term functional false-positive rate has been used in cases in which a foot may have the appearance of remaining in a plantar-flexed, varus, and medially deviated position but can passively be corrected to neutral during exam just following birth. The foot is characterized with a score of 0, 1, or 2 using the Dimeglio classification system and has been classified by some authors as a positional clubfoot. Such a foot requires only parent-administered exercise, and no long-term deformity results. With the advancement of ultrasound and increase in experience, the accuracy of diagnosis will steadily increase. The ability to recognize syndromes associated with skeletal malformations is also increasing with time (142, 148). The combination of technologic advances and improved expertise in obtaining and interpreting images will certainly lead to further progress in recognizing fetal structural abnormalities. This brings one to the question of the need for amniocentesis and karyotyping if an isolated clubfoot deformity is found. Therefore, the recommendation is that karyotyping not be done in cases where a diagnosis of isolated clubfoot deformity was made. This still appears controversial, and a geneticist should be consulted about the need for amniocentesis if the question arises. There is no attempt to provide any therapeutic intervention once an intrauterine diagnosis of clubfoot is made. The orthopaedist is only involved in counseling the family about the etiology, treatment, and prognosis, which generally alleviates fears and guilt, dispels myths, allows the parents to make personal decisions concerning the pregnancy, and allows for an improved emotional state for the family during the remainder of the pregnancy and the delivery of their child. The deformities of the clubfoot are created, in part, by malalignment of the bones at the joints and, in part, by deformation in the shapes of the bones (102, 127, 138ͱ40, 151ͱ60). The neck of the talus is short and deviated plantar-medially on the body of the talus (102, 153, 157ͱ60). This directs the articular cartilage of the head of the talus in the same plantar-medial direction. Epeldegui and Delgado (156) performed elegant microdissections of the feet of 75 stillborns, some of which had clubfoot deformities. The clubfoot is diagnosed by ultrasound in utero when there is persistent medial deviation and equinus of the foot relative to the tibia. The axis of the anterior facet of the calcaneus (2) is tilted medially in relation to the axis of the middle facet (3) in the clubfoot (image on left) compared with the normal foot (image on right). Its bony elements are the posterior articular surface of the navicular and the anterior and posterior articular facets of the calcaneus. The shape of the medial cuneiform has not been studied in the newborn, but it is trapezoid shaped in the older child with residual forefoot adductus deformity. The subtalar joint complex is severely inverted, a combination of internal rotation and plantar flexion. The calcaneus is rotated downward and inward resulting in parallel alignment with the talus in the frontal and sagittal planes. The posterior part of the calcaneus is tethered to the fibula by the calcaneofibular ligament. There is a varus deformity of the distal end of the calcaneus with medial deviation of a congruous calcaneocuboid joint in many clubfeet (78, 139, 140, 153, 155ͱ59, 161). There may be medial subluxation of the cuboid on the distal calcaneus in some feet (152, 162). The Achilles, tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, and flexor digitorum communis tendons are contracted. McKay (154) believes the talus is in neutral alignment, Goldner (163) believes that it is internally rotated, and Carroll (151, 152, 155) believes that it is externally rotated. The muscles are abnormal in both anatomical insertion and intrinsic structure (101, 106). Muscles in clubfoot are smaller than normal and there is an increase in intracellular connective tissue within the gastrocsoleus and posterior tibial muscles. A predominance of type I muscle fiber has been seen in posterior and medial muscle groups. Electron microscopic studies have shown loss of myofibrils and atrophic fibers, suggesting a regional neuronal abnormality as well (108). The ligaments are thick, with increased collagen fibers and increased cellularity (107). This is particularly true of the calcaneonavicular ligament or spring ligament and the posterior tibial tendon sheath (164).

10 mg prasugrel with amex

These children are at increased risk for developing intraabdominal tumors such as Wilms tumors medicine q10 cheap 10mg prasugrel fast delivery, adrenal carcinomas, and hepatoblastomas (59). A 9-year-old girl with infantile polio and a completely flaccid right lower extremity has a 9-cm limb-length discrepancy. Input from pediatric genetic specialists can be invaluable in evaluating all these hemihypertrophy patients when a diagnosis is not clear. It is important to study the past history of trauma, infection, neurologic conditions, abnormal skin pigmentations, or cutaneous vascular abnormalities. The orthopaedic physical exam is paramount in understanding a limb-length discrepancy. The general physical examination is important and will become more focused based on findings and clues toward the etiology are noted. Patients with questionable syndromes should be examined in shorts and with appropriate covering to evaluate for spinal deformity, pelvic obliquity, signs of spinal dysraphism, and hemiatrophy. In the seated position, the clinician should evaluate for any abnormal skin mark- ings such as hemangiomas, axillary freckling, or caf顡u lait spots. In congenital limb-length discrepancies, deficient thigh and gluteal musculature can lead to spuriously larger appearing discrepancies. With the patient in the supine position, the abdomen should be palpated to feel for any intra-abdominal mass such as a Wilms tumor that can be related to Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Examination of gait may suggest underlying neurologic conditions; spasticity (noted by a crouched gait, decreased knee extension, equinus, and raising of one arm) or weakness (Trendelenburg gait) may be uncovered. Functional compensation can be detected in gait and include hip and knee flexion and circumduction of the long limb. On the short side, the patient may exhibit an equinus contracture at the ankle and vaulting over the long limb. Upper extremity range of motion and muscle tone should be assessed in order to detect an underlying neurologic disorder. In the standing position, the level of the popliteal crease, iliac crest, and shoulders is noted and overall coronal and sagittal alignment of the spine and lower extremities is assessed. The clinician must be sure the patient has his or her knees in extension and feet flat on the ground. A fixed pelvic obliquity due to a spine deformity may be the underlying cause of an apparent leg-length discrepancy. This indirect method of measuring leg lengths has been shown to be accurate within 1. Pelvic asymmetry may occur in up to 5% of the normal population and give rise to some inaccuracy (65). Patients with nonsyndrome causes will undergo exam of the affected limb in comparison to the contralateral limb. Examination of the foot for any signs of deformity should be mandatory; the deformity should be evaluated and may be a sign of fibular hemimelia. Hip, knee, and ankle instability should be documented and may suggest congenital short femur (hip and knee instability) which is crucial to consider when planning limb lengthening. Care is needed to document joint motion, muscle girth, and neurovascular function. While supine, a detailed range of motion of the hip, knee, and ankle should be assessed for any contractures. Hip adduction contractures produce a functionally shortened limb while abduction contractures produce a functionally long limb; these can thus produce an infrapelvic obliquity (66Ͷ8). Two centimeters of limb overgrowth is present 2 years after surgical management of an ipsilateral femoral shaft and tibia fracture. In the supine position, the true and apparent leg lengths can be measured using a tape measure. The knees and hips can be flexed 90 degrees and any difference in knee heights recorded (Galeazzi sign) will suggest pathology in the femoral segment (hip joint to knee joint). Similarly, with the patient prone, differences in the height of the heel pad can be recorded demonstrating likely pathology between the distal femur and the foot. As tape measurements and block measurements are prone to error, the clinician should use them together to screen for a true leg-length discrepancy and should confirm their findings with radiography. In addition to an orthopaedic examination, an accurate assessment of maturity should be made. For review, the Tanner stage relies on the development of secondary sex characteristics to determine maturity. Factors that affect which study to order include the estimated discrepancy, the location of the discrepancy, and the age of the patient. For instance, in children under 2 years of age who are initially presenting with a leg discrepancy, the authors prefer to obtain a standing radiograph of the entire lower extremity. Although this radiograph does not allow the highest accuracy in measuring the discrepancy, it is a simple method that requires only one exposure of a potentially fidgety child. In addition, it provides an evaluation of alignment and lets the clinician see all the bones in the legs. Similarly, the clinician should personally measure all his or her own films using consistent landmarks (top of femoral head, medial femoral condyle, center of the ankle joint) to ensure as much consistency as possible. Radiographic measurements should correlate with the clinical exam findings and when discordance is present, the cause of an apparent leg-length discrepancy should be sought. Placing blocks beneath the heel of the short leg allows assessment of the combined effect of all factors that produce functional leg-length discrepancy. Clinical picture is presented of a 10-month-old infant with apparent hemihypertrophy. Although he does not have other signs of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, routine abdominal ultrasounds are needed to detect abdominal tumors. Available in many centers, Computer Scanogram has several benefits; it is quick, associated with decreased radiation (74ͷ6) and easily accommodates contractures (77) and external fixators. It is perhaps the best radiographic assessment in the young where scanograms are difficult to obtain and where full visualization of the skeleton can assist in diagnosis. Its benefit is that it is a quick single x-ray and it can give information about limb alignment and limb length. In the past, the storage of these large films was more cumbersome, but with widespread use of digital radiography, this is less of an issue and some programs can assess length without the radiographic ruler. For individuals who cannot stand well, there is no significant difference in length measurements when this technique is performed in the supine position (78). Recently, several authors have recommended these radiographs (especially the computer variants of this technique) to be the primary imaging tool to be used to diagnose and monitor leg-length discrepancies as the technique is relatively inexpensive, involves less radiation, is widely available, shows angular deformities, and can show asymmetries in the foot and pelvis (792) Recently, Sabharwal compared the use of the scanogram and digital teleoroentgenogram (with a 5% magnification factor). The authors endorsed the use of the single x-ray as this gave important information as to mechanical axis deviations not seen on a scanogram, and this limited the patient to a single radiation exposure. This technique eliminates the magnification error as the x-ray source moves to the center over each joint (83). It can be adapted to show angular deformities, but throughout all exposures the patient must remain still and thus makes it a challenge for smaller children. A: Standing alignment film of an 11-year-old girl with arthrogryposis demonstrates a functional discrepancy in length approximating 9 cm. Unfortunately, her severe knee flexion contracture precludes accurate assessment of her anatomic bone lengths. Slit scanography or scanograms are performed so that the x-ray source and the film are both adjusted to reduce parallax error and all three joints are placed on one smaller film. Indirect scanograms utilize a midline ruler between the extremities from which measurements are made; a direct scanogram places the ruler along the mechanical axis of the limb. Other imaging technologies have been described to decrease radiation exposure; however, most of these are not readily available to the practicing orthopaedic surgeon. Microdose radiography involves an x-ray source and computer detection system which yields data in about 20 seconds. The advantage of this system is its accuracy and the significantly less radiation exposure than in conventional radiographs. As another method, ultrasound has been used to measure leg-length discrepancies and has found to be slightly less accurate than x-rays (72) but eliminates all radiation.

Cheap prasugrel 10mg amex

For those with a functional foot medicine klimt discount prasugrel 10 mg with mastercard, but a leg-length discrepancy of 30% or more, amputation would be recommended. For those with a functional foot and a discrepancy of <10%, epiphysiodesis or lengthening is reasonable. It is between those two groups that the controversy regarding treatment lies, and the greater the discrepancy in length, the greater the controversy. The parents, who are the decision makers, are weighing the hope for their child to retain the limb against what that will entail. Without knowing what a child with an amputation and prosthesis versus a lengthened limb is like, their first response is almost always to lengthen the limb. They most likely have never seen a child or adult with an amputation; they visualize something horrible. At the same time, they cannot really know what a lengthened limb will be like at the end of treatment; they imagine the limb will be normal. Although they may understand that they will need two or three lengthening procedures, they cannot know what the impact will be on their child or their family, what complications they will encounter on the way, or how their child will look or function at the end of the treatment. As yet, there are but a few preliminary reports of lengthening in fibular deficiencies with predicted discrepancies >10 cm. These preliminary reports, using the Ilizarov methods, deal mainly with the extent of length achieved, often before maturity, but with little information on cosmetic and functional result (96ͱ00). One way to begin to assess the problem is to look at what amount of length is required. The combined femoral and tibial length for a girl of average height at maturity will be approximately 80 cm (37) (Table 30. A 10% discrepancy would be approximately 8 cm, a 20% discrepancy would be 16 cm, and a 30% discrepancy would be 24 cm. Reports comparing Syme amputation with lengthening are few and incomplete, but begin to give an appreciation of the problems associated with lengthening severe deficiencies (71, 103ͱ05). These reports conclude that lengthening should be reserved for those with more normal feet and less discrepancy in length, although early Syme amputation is the best treatment for the more severe problems. These authors conducted physical examination, prosthetic assessment, psychological testing, and physical performance testing and commented that the results of multistaged lengthenings for this condition would have to match these results to be justified. They currently offer lengthening to patients whose limb-length discrepancy is 20% or less. In patients with bilateral fibular deficiency, the three problems are the foot deformity, the discrepancy in length between the two limbs, and the overall shortening in height because of two short limbs. In children with bilateral fibular deficiency, there is usually little discrepancy between the two limbs, but rather a discrepancy between their height and what their normal height should be. If there is a significant difference between the length of the two limbs that cannot be solved by prosthetic adjustment, lengthening of the short limb becomes an attractive option. The amputation described by Syme (108) seems to have been accepted for adults before it was accepted for children, and its use in boys was advocated before its use in girls because it was said that the Syme amputation produced an unsightly bulkiness around the ankle. This resulted in many children receiving a transtibial amputation rather than a Syme amputation. It was subsequently learned, however, that the ankle does not enlarge following amputation in a young child, and the cosmetic appearance is excellent as the child grows. One of the major advantages of the Syme amputation is the ability to bear weight on the end of the residual limb. This is important both for prosthetic use and for instances in the home when the child will walk short distances without the prosthesis (for instance, going to the bathroom in the middle of the night). Green and Cary (114) found that patients were able to function at the average levels for their age group, and the authors did not find that adolescents were less likely to participate in athletics (114). In summary, these studies indicate that Syme amputation may be compatible with the athletic and psychological function of a nonhandicapped child. In the Boyd amputation, the talus is excised and the retained calcaneus with the heel pad is fused to the tibia. The surgery was initially devised to avoid the complication of posterior migration of the heel pad seen in some children with Syme amputation. Advantages of the Boyd amputation are that the heel pad tends to grow with the child, rather than remaining small as in the Syme amputation. In addition, the contour of the retained calcaneus improves prosthetic suspension. This can be a problem when children who do not have significant shortening of the limb are fitted for various prosthetic feet and may require a shoe lift on the normal side. However, if the residual limb is short enough to fall at the level of the contralateral calf, a Boyd amputation can easily accommodate an energy-storing prosthetic foot, and the added bulk of the residual limb end is easily hidden in the prosthesis. Eilert and Jayakumar (110) compared the two surgeries and found the migration of the heel pad to be the only complication in the Syme amputation, whereas the Boyd amputation had more perioperative wound problems and migration or improper alignment of the calcaneus. Fulp and Davids (88) compared Syme amputations to a modified Boyd amputation (where the distal tibial epiphysis and physis were removed and the calcaneus was fused to the distal tibial metaphysis). By removing the distal tibial physis and epiphysis, the residual limb was appropriately short, the heel pad was stable, and prosthetic suspension was improved. The most often cited benefit of this amputation is the end-bearing ability of the stump, which permits walking without a prosthesis and better prosthetic use. This end-bearing quality is dependent on the preservation of the unique structural anatomy of the heel pad by careful subperiosteal dissection of the calcaneus. One of the most obvious benefits of a Syme amputation (or any disarticulation) in childhood is the elimination of bony overgrowth, with the necessity for revision that accompanies through-bone amputation in the growing child. Although there are many reports of the longterm results in patients undergoing the Syme amputation, most of these have been performed for other indications. This amputation, first described by Boyd in 1939, is best indicated in the limb-deficient child. The amputation is similar to the Syme amputation except that it preserves the calcaneus with the attached heel flap and fuses it to the distal tibia. In the congenitally deformed foot found in congenital lower extremity deficiencies, the arthrodesis might favorably affect the fixation and the growth of the frequently occurring small heel pad, leaving the heel pad intact on the calcaneus. Its disadvantage is that in these same patients, the calcaneus and the distal tibia are largely cartilage, making arthrodesis difficult to achieve. If arthrodesis is not achieved, the calcaneus will migrate from beneath the fibula, requiring revision or conversion to a Syme amputation, which is not required when the heel pad alone migrates. The procedure, although most commonly used in the treatment of fibular deficiencies, has also been used in the treatment of tibial deficiencies by fusing the calcaneus to the fibula. The Syme amputation in congenital deficiencies in children has two important differences when compared to adults. First, in children with severe congenital deficiency of the lower extremity, the foot is often in severe equinus, with the heel pad proximal to the end of the tibia. This may result in difficulty in bringing the heel pad down over the end of the tibia, even after sectioning of the Achilles tendon. The malleoli are not a problem with prosthetic fitting because they do not attain the usual medial and lateral dimensions of the adult (90). Severe bowing is usually seen in the more severe deficiencies with complete absence of the fibula. With the tibial bow, the foot is displaced posterior to the weight-bearing axis that passes through the knee. If the foot is placed at the distal end of the tibia (which the parents want for cosmetic reasons), the ground reaction force places a large moment through the toe-break area, leading to premature failure of the foot component and skin problems caused by abnormal pressure. A reasonable recommendation would be to correct any significant bow at the time of Boyd amputation. The dorsal part of the incision begins at the tip of the lateral malleolus, crosses over the dorsum of the foot near the dorsiflexion crease of the ankle, and ends about 1 cm below the tip of the medial malleolus. In children with complete absence of the fibula, this landmark can be estimated by palpation of the anatomy, as well as visually. The volar part of the incision connects the ends of the dorsal incision crossing the plantar aspect of the foot at the distal end of the heel pad. In young children who have not been walking, the heel pad is often difficult to identify, and care should be taken to bring the incision far enough distally to retain sufficient tissue. Because nothing distal to this point will be saved, this incision can be carried directly down to the bone, identifying and cauterizing the bleeding vessels later when the tourniquet is released. The tendons and nerves can be pulled distally and sectioned so that they retract proximally and the vessel can be ligated or cauterized. Completing this part of the incision simplifies the most difficult and important part of the operation, which is to divide the medial and lateral ligament structures without injuring the posterior tibial vessel and its branches that supply the heel pad. The dorsalis pedis vessels are identified and cauterized, and all the tendons and nerves are pulled distally, sectioned, and allowed to retract proximally.

Saeng-Ji-Whang (Rehmannia). Prasugrel.

- How does Rehmannia work?

- What is Rehmannia?

- Dosing considerations for Rehmannia.

- Are there safety concerns?

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- Diabetes, anemia, fever, osteoporosis, allergies, or other conditions.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=97099

Order prasugrel with paypal

Increased tissue pressure first leads to obstruction of venous outflow treatment quadriceps pain cheap 10mg prasugrel with amex, causing further swelling and increased pressure. When the pressure exceeds the arteriolar pressure, muscles and nerves within the affected compartment become ischemic. Irreversible injury to these tissues begins to occur within 4 to 6 hours of onset of abnormal pressures. Fractures, crush injuries, vascular lacerations, and constrictive splints or casts are some etiologies. The most common sites of compartment syndromes in children are the lower leg in association with tibial shaft fractures and the forearm after supracondylar elbow fractures (172), but they may occur in several other sites including the hand, foot, and abdomen. Compartment syndrome of the calf can occur after placement of a child in an immediate spica cast for an ipsilateral femur fracture. The classic findings of compartment syndrome in adults are not always readily detectable in children. Decreased sensation and weak or absent motor function in the limb are important signs. In children, however, sensorimotor assessment is often challenging and unreliable because of anxiety, pain, and difficulty understanding directions or commands. Diminished capillary refill and pulselessness are late manifestations of the condition. The most reliable sign of an evolving compartment syndrome in children is escalating pain that requires increasing amounts of analgesic medications to control (172). For the child with a fracture who is experiencing increasing pain after immobilization, bivalving of the cast and splitting of the cast padding, or loosening of the splint, is the first course of treatment. If an evolving compartment syndrome is suspected, the injured extremity should be elevated but not above the level of the heart because this diminishes the mean arterial pressure of the limb, causing a reduction in perfusion that may worsen muscle ischemia. While the diagnosis of compartment syndrome is ultimately made based on careful clinical assessments, measurement of compartment pressures is sometimes useful to confirm the diagnosis (174). Decompression of the forearm can be accomplished by the volar approach of Henry or the volar ulnar approach (171). All four compartments are easily exposed through the incisions, allowing the surgeon to visually confirm that all muscle compartments, including the deep posterior compartment, are adequately released. Devitalized muscle is debrided when necessary, but extensive debridement is usually performed 36 to 72 hours later, when muscle viability is more readily determined. A: Skin incision crosses the elbow crease and enters the palm along the thenar eminence. D: the ulnar nerve and artery are retracted to expose the deep flexor compartment. A: Single-incision fasciotomy may be used to decompress all four compartments of the leg. B: Double-incision fasciotomy allows a more direct approach to the deep posterior compartment of the leg. Of those, only 1% to 10% result in a physeal bridge or bar that result in a significant disturbance of normal growth. Growth arrest after trauma is most likely to be seen in young adolescents (177), whose physes are widest and weakest compared to other age groups. Complete physeal arrest in a growing bone results in limb-length inequality or a mismatch of growth between the paired bones of the forearm (radiusεlna) and the lower leg (tibiaΦibula). Partial or incomplete arrest results in angular limb deformities or joint surface deformities. The size and location of the physeal arrest determine the kind of growth disturbance that eventually develops. Growth disturbance after fracture may result from inadequate reduction of fractures that cross the physis or destruction of normal physeal cell function after anatomic reduction of displaced fractures (177). Inadequate reduction of a physeal fracture that leaves epiphyseal bone in contact with metaphyseal bone promotes osseous bridge formation between the epiphysis and metaphysis that tethers normal growth. Despite anatomic reduction, however, physeal bridge formation also may occur after all types of Salter-Harris fractures. Arrest in these circumstances likely occurs from two other important mechanisms: diminished physeal vascularity and damage to its germinal cells (178). Epiphyseal ischemia caused by traumatic microvascular injury may cause disruption of normal physeal physiology and growth that ultimately results in a physeal bridge centrally. In contrast, diminution of metaphyseal vascularity may temporarily interfere with ossification but does not result in growth arrest (179). Direct traumatic injury to germinal cells of the growth plate, either by crushing or by shearing, can also lead to bar formation. Small bridges in children do not cause a significant growth disturbance because tethering caused by these areas is limited by the remaining healthy physis and the small bridge can grow along with the lengthening bone (182). Fractures that occur from high-energy mechanisms and fractures across undulating growth plates, such as the distal femur and proximal and distal tibia, are most frequently associated with growth disturbances that require treatment (176, 183). Iatrogenic injury from repeated forceful manipulations or inappropriate use of fixation such as screws that cross the physis may also contribute to bar formation. The second type is a central bar, which acts as a central tether to physeal growth. While many small central defects may have little clinical consequences, large ones may result in tenting of the physis that ultimately lead to distortion of the articular surface. In general, peripheral bars result in greater deformities than do central ones of the same size because of their location. B: Two years later, there is varus angulation to the distal tibia from a medial physeal bar. The Harris growth arrest line (arrow) is not parallel to the distal physis, and does not extend across the entire width of the metaphysis. After healing of most physeal fractures, followup examination and radiographs are necessary to detect potential growth disturbance. Clinical and radiographic evaluation is recommended after healing of significant physeal fractures because growth disturbance may take several years to manifest. Measurement of a length discrepancy by scanogram and narrowing of the physeal width are useful radiographic findings. The sensitivity of plain radiography is improved when the image is centered on and perpendicular to the physeal line. Partial growth arrest is more difficult to determine because angular deformities may not be clinically evident initially. On radiographs, a sclerotic bridge of bone or an asymmetric-appearing physeal line may be seen. Another sign of growth disturbance is the development of an oblique growth arrest line (185). Late findings include obvious angular deformity and joint surface deformation or incongruity. Fatsuppressed three-dimensional spoiled gradient-recalled echo imaging best defines the extent of the bridge and most easily allows the surgeon to distinguish cartilage from bone (186). Complete growth arrest may produce a mismatch of growth between paired bones or limb-length discrepancy without angular deformity. The amount of discrepancy depends on the growth rate of the affected physis and the skeletal maturity of the child. In the forearm, growth arrest of the distal radius, coupled with normal ulnar growth, may result in a length mismatch that causes ulnar sided-wrist pain. Ulnar epiphysiodesis or shortening is occasionally indicated for relief of symptoms. In the lower leg, growth arrest of the distal tibia, combined with continued fibular growth, may warrant distal fibular epiphysiodesis to prevent an excessive mismatch of length that may cause lateral calcaneal abutment with hindfoot eversion. Overall upper extremity length inequality rarely requires treatment because it has few functional consequences. For leglength inequalities, no treatment is required if the discrepancy is expected to be <2 cm at skeletal maturity. Leg-length discrepancy >2 cm, however, may affect gait and contribute to the development of back pain, knee pain, and other conditions in adulthood. Shoe inserts and modifications are options for those children with discrepancies between 2 and 5 cm whose families prefer nonsurgical treatment.

Purchase prasugrel 10 mg without prescription

The capsule can be slightly adherent to the anterior femoral neck as a result of the healing callus and inflammation medications with acetaminophen discount 10 mg prasugrel fast delivery. The surgeon should see an adequate amount of the femoral neck and the articular surface of the femoral head to ensure that he or she is properly oriented to the anatomy. The periosteum over the anterior neck is incised in a cruciate fashion and elevated, exposing the bone. This should be placed in a location that allows the hollow mill drill to cross perpendicular to the epiphyseal plate. When the proper direction is verified, the hollow mill is drilled through the anterior cortex of the femoral neck, across the physeal plate, and into the femoral head. D: the hole in the cortex can be enlarged with a curette, which also can be used to remove additional physeal plate (i). This allows the placement of grafts to provide sufficient strength for temporary stability to the epiphysis. This is preferable to several small matchstick-sized pieces because the larger grafts possess more strength. These grafts are driven into the hole, and their location is verified on the image intensifier. There have been reports of using only crutch protection, not a cast, with an incidence of further slipping in some patients (193). A drain can be used at the discretion of the surgeon, but there should be no dead space and little bleeding at the conclusion of the procedure. Those series that reported no further slipping after grafting used a spica Current Methods In Situ Fixation. Early fixation was with large nail-type devices, followed by pin fixation, which have since been replaced by cannulated screw systems in most centers. Because of the wide availability of fluoroscopic imaging, the ability to optimally position the fixation devices has improved as well. Cannulated screw systems now allow these procedures to be performed percutaneously. The surgery may be performed on either a fracture table or a radiolucent table (200, 201). Use of a fracture table allows a true lateral radiograph to be obtained, although the quality of such images in obese patients is often suboptimal and this setup requires the presence of a technician to rotate the fluoroscope. In contrast, with the patient on a radiolucent table, a technician is not needed, as the fluoroscope may be left in one position and it is easy to obtain a higher quality frog lateral radiograph; however, a true lateral can only be obtained by moving the patient. In addition, the guide wire for percutaneous fixation may be bent as the hip is rotated. When possible, the screw insertion point should be lateral to the intertrochanteric line even though the screw may not be perpendicular to the physis (203). Top: Because of their lateral starting points, both pins A and B are eccentric in the femoral head and oblique to the physis. In addition, pin A is shown exiting the posterior femoral neck before entering the epiphysis. Bottom: How pins A, B, and C will look on an anteroposterior radiograph, and how a potential blind spot exists in which a protruding screw may be missed radiographically. This reinforces the importance of imaging a pinned hip as the hip is rotated through a complete range of motion. Common sequelae with a lateral starting point are that the hardware either entirely misses or engages only a small portion of the anterior femoral head, and that such hardware also often penetrates the joint surface. Ideally, the fixation device should be located in the center of the proximal femoral epiphysis on both the anteroposterior and lateral views and should be perpendicular to the physis in both views as well (205, 206). This so-called centerΣenter position minimizes pin penetration into the joint and provides optimal fixation of the physis (68, 207Ͳ09). Additionally, it minimizes superior or posterior placement of the screw, which may place at risk the intraosseous blood supply within the head. Proper screw locations in slips of varying severity in three different cases: (A,B), (C,D), and (E,F). In all three cases, the screws enter the anterior femoral neck, are perpendicular to the physis, and are located in the center of the femoral head. The starting point is more proximal and the screw is angled progressively more posteriorly as the magnitude of slip progresses from least (A,B) to most (E,F) severe. Other authors have described a geometric analysis of the blind spot, although this technique is rarely used (210). In practice, the operative hip is taken through a full range of motion while using fluoroscopy. If a fracture table is used, this can only be done following removal of traction on the operated leg. The "approach-withdraw phenomenon" described by Moseley (211) is when the fluoroscopic appearance of the implanted hardware approaches the subchondral bone and then moves away from it. Center center pins are left 5 to 6 mm from the subchondral bone (corrected for magnification), while other pins are left 10 mm from the subchondral bone (207). Poor hardware position has been noted to correlate with poor clinical outcomes (202, 212). Injection of arthrographic dye through the hardware under fluoroscopic control and bone endoscopy are two ways that have been reported for checking for pin penetration when high-quality radiographic images cannot be obtained intraoperatively (213, 214). With current fluoroscopy machines, neither of these techniques are used on a regular basis. In addition, each of these techniques has the potential risk of flushing bone chips into the hip joint. If radiographic imaging is deemed insufficient intraoperatively, then a hip arthrogram through a standard anterior approach may be performed to better ascertain the relation of the hardware to the femoral head. Multiple clinical studies have confirmed increasing rates of pin penetration and complications with an increasing number of implants (164, 204, 209, 212, 215Ͳ18). Four previous biomechanical studies of acute physeal disruptions in animal femora stripped of soft-tissue attachments have demonstrated an increased rigidity for two-pin or two-screw constructs compared to those using only one comparable fixation device (221Ͳ24), and another found no statistically significant difference in resistance to creep in between single- and double-screw constructs in bovine femora (223). The authors of the two bovine studies stated that the biomechanical advantages of two-screw constructs were insufficient to justify the increased risk of pin penetration when two screws are used instead of one (221, 223). One additional study using bovine femora with acutely created physeal disruptions indicated that compression across the physis may be obtained if screw threads do not cross the physis, although there was no significant difference in the ultimate strength or the energy absorbed or in the degree of failure as compared to the results with a standard screw (225). In immature porcine femora stripped of soft tissues, partial and fully threaded screws have been noted to provide comparable physeal stability in vitro (226). Anteroposterior radiograph (A) demonstrates what appears to be adequate alignment of the hardware, although the frog lateral view (B) is suggestive of pin penetration. The proximity of the hardware to the joint surface had not been recognized at the time of surgery, and demonstrates the importance of leaving the pin at least 5 mm from subchondral bone, even if the hip is imaged through a range of motion at the time of surgery. This case also illustrates that only one implant can be in both a centerΣenter position and perpendicular to the physis. Physeal closure occurs in the operated hip first in most cases, and simultaneous closure occurs in fewer than 10% of cases (116, 164, 204, 227Ͳ29). Multiple studies carried out in Europe have touted the use of fixation devices without threads crossing the physis (including smooth wires, hook pins, and partially threaded screws) as a way to avoid physeal closure and to allow further growth of the proximal femur (230, 231). In series of studies with worse results, it is seen that the results are better in milder slips than in the more severe slips (202). This remodeling typically involves resorption of a portion of the prominent superior femoral neck, and has also been reported to result in changes in the proximal femoral headήeck and headγhaft angles. Studies that report proximal femoral remodeling typically report angular changes in the range of 7 to 14 degrees (29, 229, 233, 234). An open triradiate cartilage has been reported to be an indicator of more potential for such remodeling (234, 235). However, some authors have even reported remodeling after proximal femoral physeal closure (209). More contemporary reports suggest some slight improvement in head-shaft angle and reduced but persistent metaphyseal prominence (236). Another limitation is the variability in patient positioning, especially when a painful hip with synovitis is imaged at the time of presentation and a painless hip is imaged on subsequent evaluations.

Buy 10mg prasugrel

The mechanism of injury to the distal clavicle is similar to adult acromioclavicular separation medicine sans frontiers discount 10 mg prasugrel with visa. This is because the distal epiphysis of the clavicle remains a cartilaginous cap until the age of 20 years or older (6), whereas the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments are firmly attached to the thick periosteum of the clavicle. Because these injuries represent physeal disruption with herniation of bone from the periosteal tube, tremendous potential for healing and remodeling exists. Lifting the clamp on medial clavicle anteriorly reduces the metaphysis to the epiphysis (beneath Senn rake retractor) prior to figure-of-eight suture fixation. A sling or shoulder immobilizer is used for 3 weeks, followed by a graduated exercise program. Even in competitive athletes, shoulder strength and range of motion are typically not impaired after rehabilitation (17ͱ9). The occasional patient who develops late symptoms of pain and stiffness may be relieved by resection of the distal clavicle (18), with ligament reconstruction. In grade V separations, the clavicle is displaced 100% to 300% superiorly, and the clavicle lies subcutaneously. Fracture of the scapula, although rare in children, should be suspected whenever there is shoulder tenderness or swelling after trauma. Therefore, initial evaluation should include a diligent search for more serious chest injuries, such as rib fractures, pulmonary or cardiac contusion, and injury to the mediastinum. If associated with injuries to the clavicle, scapulothoracic dissociation should be suspected, and a careful assessment of the vascular and neurologic function of the ipsilateral upper extremity should be performed. Avulsion fractures of the scapula have also been reported and are a result of indirect trauma (20). Treatment of most scapular fractures consists of immobilization with a sling and swathe, followed by early shoulder motion after pain has subsided. The scapular body is encased in thick muscles, so displacement is rare and well tolerated after healing (12). Fractures of the acromion or coracoid require surgery only when severely displaced. Intra-articular fractures with substantial displacement should be restored to anatomic positions. Large glenoid rim fractures can be associated with Metaphysis Treatment of most distal clavicle fractures consists of support with a sling or shoulder immobilizer for 3 weeks. Reduction and fixation are unnecessary, except for the rare instance in which the clavicle is severely displaced in an older adolescent (12). Fracture or physeal separation of the distal clavicle is more common, and has been called pseudodislocation of the acromioclavicular joint (13). Tenderness over the acromioclavicular joint and prominence of the lateral end of the clavicle are present with fracture, physeal separation, and joint separation. Radiographs demonstrate increased distance between the coracoid process and the clavicle, compared with the opposite side. When true joint separation occurs, the injury may be a sprain, subluxation, or dislocation. The swelling and dorsal prominence of the clavicle may suggest an acromioclavicular separation. However, the distal epiphysis of the clavicle and the acromioclavicular joint remain reduced. An anterior approach is recommended for anterior glenoid fractures, and a posterior approach is used for scapular neck and glenoid fossa fractures (21). Less than 2% of glenohumeral dislocations occur in patients younger than 10 years (22). Atraumatic shoulder dislocations and chronic shoulder instability are discussed elsewhere in this book. Approximately 20% of all shoulder dislocations occur in persons between the ages of 10 and 20 years. Most displace anteriorly and produce a detachment of the anteroinferior capsule from the glenoid neck. Treatment of traumatic shoulder dislocation in children and adolescents is nonsurgical, with gentle closed reduction. This is accomplished by providing adequate pain relief, muscle relaxation, and gravity-assisted arm traction in the prone position. An alternative method is the modified Hippocratic method in which traction is applied to the arm while countertraction is applied using a folded sheet around the torso. After reduction, a shoulder immobilizer or sling is used for 2 to 3 weeks before initiating shoulder muscle strengthening. The most frequent complication is recurrent dislocation, which has an incidence between 60% and 85%, usually within 2 years of the primary dislocation (23, 24). Posterior dislocations of the shoulder may also recur and require surgical stabilization in children (25). A more detailed discussion of this injury and its treatment is found elsewhere in this book. The proximal humeral physis remains open in girls until 14 to 17 years of age and in boys until 16 to 18 years of age. Mechanisms of injury that would produce a shoulder dislocation in adults usually result in a proximal humeral fracture in children and adolescents. Metaphyseal fractures are more common before the age of 10, and epiphyseal separations are more common in adolescents. The distal fragment usually displaces in the anterior direction because the periosteum is thinner and weaker in this region. The proximal fragment is flexed and externally rotated because of the pull of the rotator cuff, whereas the distal fragment is displaced proximally because of the pull of the deltoid muscle. Remarkably, this is a relatively benign injury because of the rapid rate of remodeling with growth and the wide range of shoulder motion (26, 27). The long head of the biceps may be interposed between the fracture fragments and may impede reduction (28). They are managed in a shoulder immobilizer for 3 to 4 weeks, followed by range-of-motion exercises and gradually increased activity. These fractures are difficult to reduce and maintain in a reduced position by closed methods. Traction and cast immobilization are not recommended because these techniques are inconvenient, cumbersome, and have not been shown to improve results. Current options for management include immobilization without attempting reduction, or reduction under sedation or anesthesia with assessment of postreduction stability, and percutaneous fixation if unstable. Authors who have studied these options have concluded that most severely displaced fractures should be treated by sling and swathe immobilization (26, 27, 29). Complete displacement, 3 cm overriding, and 60 degrees of angulation may be accepted in patients who are more than 2 years from skeletal maturity. Some practitioners also believe that injuries to the dominant arm of a throwing athlete should also be treated with reduction and fixation. If unstable, the fracture was treated with percutaneous pin fixation and immobilization. If an acceptable reduction could not be achieved closed, an open reduction was performed using a deltopectoral approach. The indications for operative management of adolescent proximal Closed Reduction Method. In most fractures, the distal fragment will be displaced anteriorly through the thinner periosteum, and the proximal fragment will be abducted and externally rotated by its muscular attachments. After adequate analgesia and/or anesthesia, longitudinal traction is applied to the injured extremity, and the distal humeral fragment is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. Posteriorly directed pressure during flexion on the distal fragment will push it back inside the soft-tissue envelope, and then abduction and external rotation will reduce the fragment. Fluoroscopy is useful to assess the position of the fracture fragments during reduction. If the fracture redisplaces to an unacceptable degree with the arm at the side, then repeat reduction and percutaneous pin fixation is warranted. For minor amounts of residual varus, an abduction pillow at the side with the sling and swathe may be used. For unstable fractures and irreducible fractures, the patient should be taken to the operating room for general anesthesia.

Purchase prasugrel 10mg with amex

Even though the bones are considered strong enough for routine ambulation medicine joint pain purchase prasugrel 10mg on line, patients receive a knee immobilizer and crutches for ambulation in order to decrease pain. Once the pain resolves, these modalities are not needed as the child is weightbearing as tolerated. Three days after surgery, the dressing can be removed and motion and therapy started to facilitate recovery. Skeletal shortening is usually performed in the femur; it is rarely done in the tibia except in cases in which the femur does not lend itself to shortening. Tibia shortenings have greater risk of neurovascular complications because of the proximity and the tethering of neurovascular structures. In addition, tibia osteotomies have a higher rate of delayed union, nonunion, and compartment syndrome. Should tibia shortening be performed, prophylactic anterior compartment fasciotomy is advisable to reduce the risk of compartment syndrome. Internal fixation is more difficult in the tibia; closed techniques cannot be used because the bone is subcutaneous, and the muscles of the leg are slower to recover strength than those of the thigh. The early techniques involved making step cuts or other complex cuts in the diaphysis of the bone, using interfragmentary screws or intramedullary rods for fixation (163, 164). These techniques are only of historical interest, because better techniques with more secure fixation are now available (165). The two principal techniques in use today are diaphyseal shortening, open or closed, with intramedullary rod fixation and proximal shortening with plate fixation. Both approaches provide secure fixation and neither requires postoperative immobilization. Prior investigators had pioneered a technique of closed femoral shortening with an intramedullary saw set which allows the procedure to be performed entirely within the medullary cavity and without direct approach to the shaft of the femur (166, 167). The femur diaphysis is cut at two levels; the intervening bone segment is fragmented, shortened, and stabilized with a locked intramedullary nail; advantages are a minimal approach and less soft-tissue dissection. The nail provides outstanding fixation and the patient may weight bear as tolerated. This procedure is limited to patients with bones that can accommodate the intramedullary saw and standard locked nails (usually 9 to 10 mm of medullary space is required). This technique is usually precluded in patients with open proximal femoral growth plates due to risk of growth arrest or avascular necrosis; the latter results from damage to the lateral ascending femoral circumflex vessels along the femoral neck as the saw and the nail may enter through the piriformis fossa. Other risks to this surgery include potential fat embolism syndrome as a result of closed femoral shaft reaming (168). Because the fragmented bone stays in situ, patients with closed femoral shortening may temporarily complain of the large callus of bone that develops from the incorporation of the comminuted bone fragments that remain. Alternatively, an open approach can be used to remove a segment of bone which is stabilized by a plate or possibly an intramedullary nail. A significant advantage of proximal femoral shortening (at the level of the lesser trochanter) with plate fixation is that the resection level is proximal to most of the quadriceps origin. As such, the muscle and bone length relationship is preserved and patients recover strength quickly. The open approach allows exact measure of the amount of bone to be removed from the patient. This is an advantage because closed femoral shortening does not allow precise measurement of shortening. On the other hand, the open approach requires a large incision on the lateral thigh and requires elevation of the vastus lateralis muscle. The plate is placed on the lateral aspect of the femur, thus making it potentially prominent and painful. In these cases, a second later operation of moderate magnitude is needed to remove the plate. Preoperatively, the amount of bone to be shortened is determined from scanogram measurements; anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the femur are required to measure the diameter of the diaphysis and to assess for anatomic deformity that would preclude intramedullary fixation. Intraoperatively, the patient is placed supine with a bump that allows exposure to the buttock. A guide pin is placed percutaneously to the appropriate starting point as dictated by the proximal nail geometry [either the piriformis fossa (straight nail) or the trochanteric tip (trochanteric entry nail)]. Acute respiratory distress syndrome has been reported during or following closed intramedullary shortening and may be the result of fat embolization caused by reaming an intact femur (168). In order to prevent this rare but significant complication, we routinely vent the femur with a large cannulated drill bit placed into the junction of the distal metaphysis and diaphysis. We further advise the anesthesia team of the risk so that they can adequately hydrate the patient and keep the PaO2 high during the reaming process. A proximal and distal k-wires are placed to detect inadvertent malrotation after osteotomy, and then the osteotomy levels are identified. We prefer to plan the levels in the proximal onethird of the femur in order to minimize the amount of quadriceps muscle that would be functionally lengthened. Alternatively for shorter lengthenings, cuts could be placed so that the shortening is from the isthmus of the femur where the internal diameter is least; this has the advantage of more cylindrical reaming and eventual easier cutting in the cylindrical diaphysis. Occasionally, the cuts cannot be completed because the femur is not perfectly cylindrical and the saw will not fully cut a portion of the bone. The surgeon then passes a guide rod down the femoral shaft which facilitates the placement of the intramedullary rod. The intramedullary bone saw set is a required equipment in addition to all the equipment necessary for closed intramedullary femoral rod placement. The saw consists of two shafts: an inner one with a saw blade on the end and an outer one with a bushing set eccentrically on it just proximal to the saw blade. The size of the bushing on the saw defines the size of the saw, which ranges from 12 to 17 mm. On a threaded portion of the outer shaft is a measuring device that consists of a trochanteric rest distally and a locking nut proximally. This is hooked on the distal end of the piece of bone to be split and is driven out of the bone with the slotted hammer. The measuring device is set to allow the saw to pass down the shaft to the distance that was determined on the preoperative radiographs. It is of critical importance that the trochanteric rest be held firmly against the tip of the greater trochanter at all times. Not only is this the reference point for all measurements, but it also ensures that the saw remains in the same cut in the bone. To begin the osteotomy, the index scale locking nut is pulled back and the indexing scale is advanced one hole past the zero mark. The T handle is then used to turn the saw through one or two complete revolutions. Each time after it is advanced, the saw is turned 360 degrees, cutting a small thickness of the bone. When the saw has been advanced to the number 20 on the indexing device, it has reached its maximal penetration. Occasionally, after the anterior cortex has been cut through, the saw catches when it is rotated. It is important to make certain that the measuring device is held firmly against the tip of the trochanter. If this fails to correct the problem, the saw should be retracted three or four stops and then advanced one stop at a time. Care should be exercised in the procedure because it is possible to break the saw. The saw is now pushed down the shaft until the trochanteric rest sits firmly against the tip of the trochanter, and the entire procedure of cutting the bone is repeated at the proximal osteotomy site. This can be done by using the distal fragment of the femoral shaft as a lever to break this intercalary piece of bone off the proximal fragment. If this is not possible, either of the two methods used to complete the first osteotomy can be used. With a firm grasp on the osteotome and with the hand held firmly against the thigh, the osteotome is struck sharply with a mallet to complete the osteotomy. The intercalary fragment of femoral shaft created by the two osteotomies must now be split and moved out of the way to allow the femur to shorten.

Buy prasugrel with a mastercard

Physical examination usually reveals tenderness directly over the plica as it comes over the medial femoral condyle to the infrapatellar fat pad treatment dry macular degeneration buy discount prasugrel 10mg on line, and possibly a palpable snapping sensation as the knee is flexed from 30 to 60 degrees of flexion while the patient is weight bearing or standing. In some cases, synovial plicae are associated with signs of lateral patellar instability. Plain radiographs are normal, and other imaging studies have not proven to be of value. This syndrome is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion after other causes of knee pain and popping have been ruled out. Symptomatic plicae demonstrate hypertrophy and inflammation which lead to thickening and eventual fibrosis. With significant fibrosis, changes in the articular surface and even subchondral bone may occur (310). Arthroscopic resection of the plica is indicated in those rare cases, with excellent results expected in 90% of cases (307, 312ͳ20). Simple division of the plica has been associated with recurrence and is not recommended. At the time of surgical resection, the joint is thoroughly examined for other causes of internal derangement such as meniscal tear or patellar maltracking. Originally described by Hoffa (321) in 1904, very little is known about this condition in children or adolescents. Anatomic studies of the fat pad have revealed a densely innervated tissue, and because of its anatomic location, its role as a possible cause of anterior knee pain is debated (322ͳ26). In the latter condition, maximal tenderness is at the inferior pole of the patella. In Hoffa syndrome, the maximal area of tenderness is at the anterior joint line on either side and deep to the patellar tendon. A diagnostic intra-articular local anesthetic injection directly into the fat pad may be of help in those patients whose symptoms fail to resolve. There is little information as to the efficacy of surgical management for this condition (327). Because such doubt exists as to the validity of the diagnosis, surgical recommendations as a treatment option cannot be made (328). However, anterior knee pain in children and adolescents can exist in the absence of positive physical findings for any of the pathologic conditions causing knee pain. The pain is made worse with physical activity such as running, jumping, squatting, going up and down stairs, or after prolonged sitting with the knee in flexed position. Physical examination may reveal so-called miserable malalignment including excessive internal femoral torsion, external tibial torsion, mild genu valgum with medial deviation of the patella, and a tendency to pes planus or foot pronation. The suprapatellar (superior) plica, the midial plica, which is one of the most commonly symptomatic, and the inferior plica (ligamentum mucosum), which overlies the anterior cruciate ligament. The patella may be hypermobile and have some evidence of maltracking, but without signs of patellar subluxation or dislocation. There may be atrophy of the quadriceps and patellar crepitus with flexion and extension of the knee or a patellar compression test. Examination of patellar tracking should include assessment of the Q angle, lateral tilt, and lateral tracking. Historically, the term "chondromalacia patellae" has been used to describe this entity (330). In children and adolescents with idiopathic anterior knee pain, however, the articular surface is often normal. Articular cartilage has no sensory nerve endings, and with the lack of articular cartilage changes in these patients, the source of the pain is not definite. Therefore, one should avoid the use of the term "chondromalacia patellae" in the case of patients with idiopathic anterior knee pain. In what should be a classic article, Sandow and Goodfellow reported on the natural history of untreated anterior knee pain in adolescent girls followed up for 2 to 8 years (331). The symptoms of most of these patients resolved over time or were significantly improved. Treatment should be almost exclusively nonsurgical and consist of activity modification, flexibility exercises of the quadriceps and hamstrings, strengthening exercises of the same muscle groups, and the use of other modalities such as ice, heat, ultrasound, and transcutaneous electrical muscle stimulation (331ͳ38). Some patients will benefit from foot orthotics, especially if pes planus is a component of the problem. Knee orthotics such as a patellar stabilization brace or patellar sleeve or strap may also be beneficial. In summary, idiopathic anterior knee pain in adolescents is commonly referred to as a "headache of the knee" (331). The orthopaedist must assume the role of the "knee psychiatrist" when treating these patients, with a careful and complete clinical history and physical examination, and almost evangelical enthusiasm for nonoperative treatment. It is essential that the patient and his or her family understand that the course of symptoms may be prolonged, but with growth and maturation, activity modification, and an organized rehabilitation program, there is excellent prognosis for return to physical activities and improvement in symptoms (328). There is usually no associated intra-articular pathology in children with this symptom (339). Transillumination of the cyst or ultrasound can document the cystic nature of the lesion and rule out solid soft-tissue lesions such as rhabdomyosarcoma. Anatomically, the cyst arises from the posterior aspect of the knee joint itself, between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the semimembranosus. Although it may be firmly attached to the fascia of the medial gastrocnemius, it almost always communicates with the knee joint. Spontaneous resolution of popliteal cysts tends to occur, but this often takes up to 12 to 24 months (339). Surgical excision is rarely indicated and should probably be considered only in cases where rapid enlargement has occurred or pain is a major feature. Recurrence rates are significant after surgery, and the treatment of choice should be watchful waiting and parental reassurance. Shin pain refers to a condition that produces pain and discomfort in the leg due to repetitive running or hiking (341). The condition is limited to musculotendinous inflammations and diagnosis should exclude stress fractures and ischemic disorders. Nevertheless, stress fracture and chronic exertional compartment syndrome are part of the differential diagnosis of leg pain in the running athlete. The pain is usually appreciated on the posteromedial border of the tibia from an area approximately 4 cm above the ankle to a more proximal level approximately 10 to 12 cm proximal. It was felt that symptoms were due to an inflammation and overload of the posterior tibial tendon (339, 340). Drez (342) has used the term "medial tibial stress syndrome" to describe this pain. Postmortem studies have demonstrated that the site of pain along the posteromedial border of the tibia corresponds to the medial origin of the soleus muscle (343). The physical examination consistently demonstrates tenderness along the posteromedial border of the tibia, centered at the junction of the proximal two-thirds and the distal one-third. There is no pain along the subcutaneous border of the tibia, and active and passive motion of the foot and ankle are usually negative. The common presentation is the discovery of an asymptomatic mass by the mother of the Radiographic Features. In medial tibial stress syndrome, there is increased uptake in a longitudinal pattern along the posteromedial tibial cortex at the exact site of pain and tenderness (344, 345). Tibial stress fractures demonstrate a transverse pattern of increased uptake (344, 345). With exercise and muscle contraction, significant elevations of intracompartmental pressure, up to 80 mm Hg, occur (349, 350). Muscle weight and size increase up to 20% during exercise and, because of the unyielding compartment space, lead to increased pressure that eventually exceeds the capillary filling pressure, causing ischemia and pain (350). The ischemia is never severe enough to cause muscle necrosis in exertional compartment syndrome. Shin pain in the adolescent athlete can be due to a multitude of causes and should be evaluated for a specific diagnosis. Possible causes of shin pain include medial tibial stress syndrome, stress fracture, exertional compartment syndrome, benign or malignant tumor, infection, and other rare causes. Medial tibial stress syndrome is associated with a sudden increase in athletic activity, especially running (346).