Buy generic tolterodine online

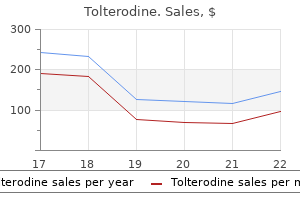

The gluteus maximus muscle is susceptible to trauma and to wear and tear from overuse and misuse and to the development of myofascial pain syndrome medications gout cheap 1 mg tolterodine with visa, which may also be associated with gluteal bursitis. Blunt trauma to the muscle may also incite gluteus maximus myofascial pain syndrome. The trigger point is pathognomonic lesion of myofascial pain syndrome and is characterized by a local point of exquisite tenderness in the affected muscle. In Atlas of pain management injection techniques, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, p 379. In addition, involuntary withdrawal of the stimulated muscle, called a jump sign, often occurs and is characteristic of myofascial pain syndrome. In spite of this consistent physical finding, the pathophysiology of the myofascial trigger point remains elusive, although trigger points are believed to be caused by microtrauma to the affected muscle. The gluteus maximus muscle seems to be particularly susceptible to stress-induced myofascial pain syndrome. Because of the lack of objective diagnostic testing, the clinician must rule out other coexisting disease processes that may mimic gluteus maximus syndrome (see "Differential Diagnosis"). For this reason, a targeted history and physical examination, with a systematic search for trigger points and identification of a positive jump sign, must be carried out in every patient suspected of suffering from gluteus maximus syndrome. The use of electrodiagnostic and radiographic testing can identify coexisting disorders such as rectal or pelvic tumors or lumbosacral nerve lesions. The clinician must also identify coexisting psychological and behavioral abnormalities that may mask or exacerbate the symptoms associated with gluteus maximus syndrome. SignS and SympTomS the trigger point is the pathognomonic lesion of gluteus maximus syndrome, and it is characterized by a local point of exquisite tenderness in the gluteus maximus muscle. Mechanical stimulation of the trigger point by palpation or stretching produces both intense local pain in the medial and lower aspects of the muscle TreaTmenT Treatment is focused on eliminating the myofascial trigger and achieving relaxation of the affected muscle. The mechanism of action of the treatment modalities used is poorly understood, so an element of trial and error is involved in developing a treatment plan. Because underlying depression and anxiety are present in many patients, antidepressants are an integral part of most treatment plans. For patients who do not respond to these traditional measures, consideration should be given to the use of botulinum toxin type A; although not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication, the injection of minute quantities of botulinum toxin type A directly into trigger points has been successful in the treatment of persistent gluteus maximus syndrome. Clinical Pearls Although gluteus maximus syndrome is a common disorder, it is often misdiagnosed. Therefore, in patients suspected of suffering from gluteus maximus syndrome, a careful evaluation to identify underlying disease processes is mandatory. Gluteus maximus syndrome often coexists with various somatic and psychological disorders. With internal rotation of the femur, the tendinous insertion and belly of the muscle can compress the sciatic nerve; if this compression persists, it can cause entrapment of the nerve. The symptoms of piriformis syndrome usually begin after direct trauma to the sacroiliac and gluteal region. SignS and SympTomS Initial symptoms include severe pain in the buttocks that may radiate into the lower extremity and foot. Patients suffering from piriformis syndrome may develop an altered gait, leading to coexistent sacroiliac, back, and hip pain that confuses the clinical picture. Palpation of the piriformis muscle reveals tenderness and a swollen, indurated muscle belly. A positive Tinel sign over the sciatic nerve as it passes beneath the piriformis muscle is often present. Weakness of the affected gluteal muscles and lower extremity and, ultimately, muscle wasting are seen in patients with advanced, untreated cases of piriformis syndrome. Plain radiographs of the back, hip, and pelvis are indicated in all patients who present with Piriformis m. Injection in the region of the sciatic nerve at this level serves as both a diagnostic and a therapeutic maneuver. In addition, most patients with lumbar radiculopathy have back pain associated with reflex, motor, and sensory changes, whereas patients with piriformis syndrome have only secondary back pain and no reflex changes. The motor and sensory changes of piriformis syndrome are limited to the distribution of the sciatic nerve below the sciatic notch. The left arrow in A shows an atrophic and asymmetric piriformis muscle, and the arrow in B shows bone marrow edema and tendinopathy. TreaTmenT Initial treatment of the pain and functional disability associated with piriformis syndrome includes a combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and physical therapy. If the patient sleeps on his or her side, placing a pillow between the legs may be helpful. If the patient is suffering from significant paresthesias, gabapentin may be added. For patients who do not respond to these treatment modalities, injection of local anesthetic and methylprednisolone in the region of the sciatic nerve at the level of the piriformis muscle is a reasonable next step. CompliCaTionS and piTfallS the main complications of injection in the region of the sciatic nerve are ecchymosis and hematoma. Because paresthesia is elicited with the injection technique, needle-induced trauma to the sciatic nerve is a possibility. By advancing the needle slowly and withdrawing the needle slightly away from the nerve, injury to the sciatic nerve can be avoided. Clinical Pearls Because patients suffering from piriformis syndrome may develop an altered gait, resulting in coexistent sacroiliac, back, and hip pain, careful physical examination and appropriate testing are required to sort out the diagnostic possibilities. Transverse magnetic resonance images (not shown) suggested the presence of a fibrolipomatous hamartoma, although a plexiform neurofibroma was also considered. Acute injuries are often caused by direct trauma to the bursa from falls onto the buttocks or by overuse, such as prolonged riding of horses or bicycles. SignS and SympTomS Patients suffering from ischiogluteal bursitis frequently complain of pain at the base of the buttock with resisted extension of the lower extremity. The pain is localized to the area over the ischial tuberosity; referred pain is noted in the hamstring muscle, which may develop coexistent tendinitis. Patients are often unable to sleep on the affected hip and may complain of a sharp, catching sensation when they extend and flex the hip, especially on first awakening. Magnetic resonance imaging is indicated if disruption of the hamstring musculotendinous unit is suspected. The injection technique described later serves as both a diagnostic and a therapeutic maneuver and is also used to treat hamstring tendinitis. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and antinuclear antibody testing, are indicated if collagen vascular disease is suspected. Plain radiography and radionuclide bone scanning are indicated in the presence of trauma or if tumor is a possibility. To inject the ischiogluteal bursa, the patient is placed in the lateral position with the affected side upward and the affected leg flexed at the knee. Should paresthesia occur, the needle is immediately withdrawn and is repositioned more medially. The needle is then carefully advanced at that point through the skin, subcutaneous tissues, muscle, and tendon until it impinges on the bone of the ischial tuberosity. Care must be taken to keep the needle in the midline and not to advance it laterally, to avoid contacting the sciatic nerve. After careful aspiration, and if no paresthesia is present, the contents of the syringe are gently injected into the bursa. Because of the proximity to the sciatic nerve, injection for ischiogluteal bursitis should be performed only by those familiar with the regional anatomy and experienced in the technique. Many patients complain of a transient increase in pain after injection of the affected bursa and tendons, and patients should be warned of this possibility. If patients continue to engage in the repetitive activities responsible for ischiogluteal bursitis, improvement will be limited. Tumors of the hip and pelvis should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of ischiogluteal bursitis.

Atlantic Cedarwood Oil (Atlantic Cedar). Tolterodine.

- How does Atlantic Cedar work?

- Hair loss when combined with other oils.

- Insect repellent.

- What is Atlantic Cedar?

- Are there safety concerns?

- Dosing considerations for Atlantic Cedar.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=97063

2mg tolterodine overnight delivery

Supplemental first trimester progesterone therapy appeared to have a beneficial therapeutic effect in some patients treatment 1st metatarsal fracture generic tolterodine 1mg visa. There is an infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells within the stroma and glands. The diagnosis of chronic endometritis rests primarily on the presence of plasma cells within the endometrial stroma and usually the other features noted below. The normal glandular and stromal response to the hormonal milieu of the menstrual cycle is usually diminished, often resulting in an inactive appearance or gland-to-gland or gland-to-stroma dyssynchrony. Histologic dating is thus not usually reliable, although otherwise normal-appearing proliferative or secretory endometrium is seen in some cases. In addition to plasma cells, neutrophils are present and infiltrate the surface epithelium. Actinomyces infection of the endometrium is considered under Intrauterine Device-related Changes. These and other studies suggest that the presence of occasional endometrial plasma cells, when it is the only abnormal finding, usually has little or no clinical significance. Correlation of the histology with the clinical findings (including laparoscopic and culture results) facilitates the diagnosis. Aside from an endometrial infection, endometrial plasma cells may be see in anovulatory/disordered proliferative endometria with menstrual changes (Gilmore et al. When fragments of endocervical tissue containing plasma cells are present in an endometrial curettage specimen, misdiagnosis of chronic endometritis can occur if the endocervical origin of the tissue is not appreciated. This uncommon finding, which is of unknown clinical significance, is typically encountered in premenopausal women who present with abnormal vaginal bleeding. The lesion consists of a focal periglandular infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils; plasma cells are absent. The infiltrate typically extends into the gland lumen with disruption or partial or subtotal necrosis of the glandular epithelium, the appearance resembling a crypt abscess. The microscopic findings are generally similar to those in the uterine cervix (Chapter 4). Differences from the latter include an absence of a band-like distribution and more numerous ill-defined aggregates of large lymphoid cells, the appearance resembling reactive germinal centers but usually without a mantle of mature lymphocytes. One endometrial gland is partly destroyed by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate but without plasma cells. Left: Except for the surface epithelium, the endometrium is completely replaced by a dense lymphoid infiltrate. Right: High-power view of the infiltrate reveals a mixed population of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and immunoblasts. A unique lesion consisted of intravascular blast cells within an endometrial polyp in a woman with chronic endometritis (Bryant et al. The cells had a polyclonal pattern for T-cell receptor and but clonal rearrangement for IgH. The findings raised concern for an intravascular lymphoma, but hematologic assessment and follow-up were negative. Granulomas are usually related to a prior operation or are idiopathic, less commonly to infection (tuberculous, fungal, parasitic), foreign material, tumor-derived keratin, or sarcoidosis. Kelly and McCluggage have described idiopathic uterine granulomas within the myometrium or cervical stroma that were typically multiple and related to thin-walled vascular channels, although there was no evidence of vasculitis. Necrotic granulomas, in which palisaded histiocytes (including giant cells) surround necrotic zones, can occur after diathermy/laser endometrial ablation or with the Mirena coil (see Intrauterine Device-related changes). Ablation-related granulomas are typically associated with necrotic tissue and refractile brown hematoidin-like pigment and/or black (carbon) pigment. Xanthogranulomatous endometritis typically occurs in postmenopausal women who present with vaginal bleeding or discharge. Necrotic, friable, yellow-brown tissue is obtained by D&C or lines the endometrial cavity of a hysterectomy specimen. Neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, hemosiderin-laden histiocytes, and foreign-body giant cells are often admixed. Other findings may include cholesterol crystals, focal calcification, necrosis, and radiation-induced changes. The pathogenesis is likely related to cervical obstruction resulting in pyometra, hematometra, endometrial necrosis, or combinations thereof. Radiation-induced tumor necrosis and bacterial infection may be additional factors in some cases. The differential diagnosis includes malacoplakia (see below) and endometrial stromal foam cells occurring in some cases of endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma (Chapter 8). The endometrium may be grossly thickened, nodular or polypoid, soft, yellow to brown, and focally hemorrhagic. The nodules, which were an incidental microscopic finding in curettage specimens in women of reproductive age, were solitary, free-floating, and up to 1. Small cytoplasmic vacuoles may impart a signet-ring-like or plasmacytoid appearance. Mitotic figures may be found and occasionally are focally numerous (up to 4 mf/hpf). The distinctive appearance of the histiocytes, their nodular arrangement, and the absence of lipid and/or pigment differ from those of usual histiocytic or xanthogranulomatous endometritis. As noted previously, eosinophils may be part of a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in endometritis. Surface papillarity is conspicuous and underlying endometrial stroma demonstrates a striking spindled morphology. Palisading of histiocytes along the endometrial surface creates an appearance which has been likened to a synovial membrane. The stroma may be fibrotic and contain atypical fibroblasts and vessels with thickened walls. Distinction from preneoplastic or neoplastic changes is facilitated by awareness of the history and appreciation of the typical histologic findings, including a spotty distribution and an absence of both glandular crowding and mitotic activity. Features favoring condyloma include premenopausal age, associated cervical condyloma, koilocytosis, papillomatosis, and no myometrial invasion. Herpetic endometritis is a rare finding that may be associated with herpetic cervicitis or diagnosed at autopsy in patients with disseminated infection. The endometrial stroma may contain prominent numbers of lymphocytes, lymphoid follicles with germinal centers, and plasma cells. Polyps are found in up to 25% of endometrial biopsy specimens performed for abnormal uterine bleeding, although they are often an incidental finding. Occasionally polyps prolapse into the endocervix and may mimic an endocervical polyp. Endometrial polyps may be associated with an increased risk of hyperplasia or carcinoma away from the polyp. Polyps are the most common endometrial lesion associated with tamoxifen therapy, being present in up to a third of these patients. Tamoxifen-related polyps tend to be larger, more commonly multiple, and are more likely to recur; some have distinctive histologic features as noted below. Polyps have a narrow to broad base, a usually smooth external surface, and an often cystic and/or fibrotic sectioned surface. Focal hemorrhage may be seen, particularly at their tips, due to torsion and infarction. A large polyp fills the endometrial cavity and extends into the endocervical canal. The polyp, which occupies most of the left half of the field, has a glandular pattern and a fibrotic stroma that differ in appearance from the admixed proliferative endometrium. This degree of gland crowding and irregularity is common in endometrial polyps and should not lead to the diagnosis of simple hyperplasia. This example of mucinous metaplasia in a polyp demonstrates a prominent fibrous stroma. Cells with more uniform nuclei are interspersed among the cells with atypical nuclei.

Discount generic tolterodine canada

Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors Chiang S symptoms ketoacidosis 2 mg tolterodine sale, Gilks B, Huntsman D, et al. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex-cord tumors: A clinicopathologic analysis of fourteen cases. A uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor associated with tamoxifen treatment: A case report and literature review. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian sex cord tumour is an immunohistochemically polyphenotypic neoplasm which exhibits coexpression of epithelial, myoid and sex cord markers. Uterine tumors resembling ovarian sex cord tumors are polyphenotypic neoplasms with true sex cord differentiation. Uterine tumour resembling ovarian se cord tumour: first report of a large series with follow-up. Uterine and extrauterine plexiform tumourlets are sex-cord-like tumours with myoid features. Retiform uterine tumours resembling ovarian sex cord tumours: A comparative immunohistochemical study with retiform structures of the female genital tract. Prognostic value of the diagnostic criteria distinguishing endometrial stromal sarcoma, low grade from undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma, 2 entities within the invasive endometrial stromal neoplasia family. Predictive histologic factors in carcinosarcoma of the uterus: A multi-institutional study. Prognostic factors in uterine carcinosarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 25 patients. Sarcomatous component in uterine carcinosarcomas correlates with advanced stage and poorer prognosis. Stage I uterine carcinosarcoma: Matched cohort analyses for lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and brachytherapy. Carcinosarcomas of the female genital tract: A pathologic study of 29 metastatic tumors: Further evidence for the dominant role of the epithelial component and the conversion theory of histogenesis. Prognostic factors for disease-free and overall survival of patients with uterine carcinosarcoma. Therapy modalities, prognostic factors, and outcome of the primary cervical carcinosarcoma. Primary yolk sac tumor concomitant with carcinosarcoma originating from the endometrium: case report. Evaluation of the relationship between adenosarcoma and carcinosarcoma and a hypothesis of the histogenesis of uterine sarcomas. Uterine carcinosarcomas: Clinical, histopathologic and immunohistochemical characteristics. Uterine carcinosarcoma: Immunohistochemical studies on tissue microarrays with focus on potential therapeutic targets. Molecular markers and clinical behavior of uterine carcinosarcomas: Focus on the epithelial tumor component. Genomic characterization of histologically distinct components of uterine carcinosarcoma. Carcinosarcoma of the uterine cervix: A report of eight cases with immunohistochemical analysis and evaluation of human papillomavirus status. In-depth molecular profiling of the biphasic components of uterine carcinosarcomas. Interobserver reproducibility among gynecologic pathologists in diagnosing heterologous osteosarcomatous component in gynecologic tract carcinosarcomas. Monoclonal origins of malignant mixed tumors (carcinosarcomas): Evidence for a divergent histogenesis. Molecular evidence that most but not all carcinosarcomas of the uterus are combination tumors. Clinicopathologic analysis of c-kit expression in carcinosarcomas and leiomyosarcoma of the uterine corpus. Papillary adenofibroma of the uterus: Report of a case involved by adenocarcinoma and review of the literature. Adenofibroma and adenosarcoma of the uterus: A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Uterine adenosarcomas: Diagnostic use of the proliferation marker Ki-67 as an adjunct to morphologic diagnosis. Uterine adenosarcomas: A dual-institution update on staging, prognosis and survival. Uterine adenosarcoma: An analysis on management, outcomes, and risk factors for recurrence. Adenosarcoma of the uterus: A Gynecologic Oncology Group clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Uterine adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth versus uterine carcinosarcoma: Comparison of treatment and survival. Significance of lymph node metastasis on survival of women with uterine adenosarcoma. Adenomyoma with pseudoinvasive growth pattern and serosal penetration mimicking endometrial carcinoma. Uterine adenomyoma: A clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and review of the literature. Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus: A clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Atypical polypoid adenomyofibromas (atypical polypoid adenomyomas) of the uterus: A clinicopathologic study of 55 cases.

Order 2mg tolterodine visa

Both the quadriceps tendon and the prepatellar bursa are subject to inflammation from overuse treatment plan discount tolterodine 4 mg with amex, misuse, or direct trauma. The tendon fibers, called expansions, are vulnerable to strain, and the tendon proper is subject to the development of tendinitis. The suprapatellar, infrapatellar, and prepatellar bursae may also become inflamed with dysfunction of the quadriceps tendon. Anything that alters the normal biomechanics of the knee can result in inflammation of the prepatellar bursa. Longitudinal midline scan over the inferior pole of patella in a 42-year-old garden paver presenting with chronic anterior knee pain. The prepatellar bursa (between heavy arrows) is markedly thickened and distended by a combination of synovial proliferation, a finding indicating chronic irritation and fluid. The bursa lies superficial to the patella and the normal fibrillary pattern of the patella tendon (thin arrow). The injection technique described is extremely effective in treating the pain of prepatellar bursitis. The superficial infrapatellar bursa is vulnerable to injury from both acute trauma and repeated microtrauma. Acute injuries are caused by direct trauma to the bursa during falls onto the knee or patellar fracture. If inflammation of the superficial infrapatellar bursa becomes chronic, calcification may occur. SignS and SympTomS Patients with superficial infrapatellar bursitis complain of pain and swelling in the anterior knee over the patella that can radiate superiorly and inferiorly into the surrounding area. Superficial infrapatellar bursitis often coexists with arthritis and tendinitis of the knee, which can confuse the clinical picture. Both the quadriceps tendon and the superficial infrapatellar bursa are subject to inflammation from overuse, misuse, or direct trauma. Anything that alters the normal biomechanics of the knee can result in inflammation of the superficial infrapatellar bursa. If patients do not experience rapid improvement, injection is a reasonable next step. To inject the superficial infrapatellar bursa, the patient is placed in the supine position with a rolled blanket underneath the knee to flex the joint gently. Just below this point, the needle is inserted at a 45-degree angle to slide subcutaneously into the superficial infrapatellar bursa. If the needle strikes the patella, it is withdrawn slightly and is redirected with a more inferior trajectory. When the needle is positioned in proximity to the superficial infrapatellar bursa, the contents of the syringe are gently injected. A fluid level within the bursa is evident on this sagittal fast spin-echo magnetic resonance image. Antinuclear antibody testing is indicated if collagen vascular disease is suspected. If infection is a possibility, aspiration, Gram stain, and culture of bursal fluid should be performed on an emergency basis. The injection technique described is extremely effective in treating the pain of superficial infrapatellar bursitis. The deep infrapatellar bursa is vulnerable to injury from both acute trauma and repeated microtrauma. If inflammation of the deep infrapatellar bursa becomes chronic, calcification may occur. They may also complain of a sharp "catching" sensation with range of motion of the knee, especially on first arising. Infrapatellar bursitis often coexists with arthritis and tendinitis of the knee, which can confuse the clinical picture. Physical examination may reveal point tenderness in the anterior knee just below the patella. The deep infrapatellar bursa is not as susceptible to infection as is the superficial infrapatellar bursa. Antinuclear SignS and SympTomS Patients with deep infrapatellar bursitis complain of pain and swelling in the anterior knee below the patella that can radiate inferiorly into the surrounding area. Both the quadriceps tendon and the deep infrapatellar bursa are subject to inflammation from overuse, misuse, or direct trauma. Anything that alters the normal biomechanics of the knee can result in inflammation of the deep infrapatellar bursa. To inject the deep infrapatellar bursa, the patient is placed in the supine position with a rolled blanket underneath the knee to flex the joint gently. The skin overlying the medial portion of the lower margin of the patella is prepared with antiseptic solution. Just below this point, the needle is inserted at a right angle to the patella to slide beneath the patellar ligament into the deep infrapatellar bursa. When the needle is positioned in proximity to the deep infrapatellar bursa, the contents of the syringe are gently injected. Longitudinal midline scan over the distal patella in a 24-year-old middle-distance runner presenting with the recent onset of pain over the distal patella tendon. The injection technique described is extremely effective in treating the pain of deep infrapatellar bursitis. Although the disease can affect all ages, most cases occur in adolescents, with a peak incidence at approximately 13 years of age. Boys and men are affected two to three times more often than are girls and women, although some investigators believe that the number of female cases is on the rise as a result of increased female participation in competitive sports. The pain and functional disability associated with osgood-Schlatter disease are bilateral in 25% to 30% of patients, and one side often has more severe symptoms. The quadriceps tendon is made up of fibers from the four muscles that constitute the quadriceps muscle: vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris. The tendons of these muscles converge and unite to form a single, exceedingly strong tendon. The patella functions as a sesamoid bone within the quadriceps tendon, with fibers of the tendon expanding around the patella and forming the medial and lateral patella retinacula, which strengthen the knee joint. The tibial tuberosity is the nidus of the pain and functional disability associated with osgood-Schlatter disease because the repetitive stresses applied to the tibial tuberosity by contraction of the quadriceps mechanism result in apophysitis and heterotopic bone growth. These responses to the damage induced by repetitive stress are most often seen during the period of rapid skeletal growth associated with adolescence, although as mentioned earlier, this disease has been reported in all age groups. Patients note increased pain on walking down slopes or up and down stairs, as well as during any activity that involves contraction of the quadriceps mechanism. Activity using the knee makes the pain worse, whereas rest and heat provide some relief. A large ossicle, 4 cm in length, seen at the tibial tubercle, separated from the tubercle. Active resisted extension of the knee reproduces the pain, as does pressure on the tibial tuberosity. The quadriceps tendon is also subject to acute calcific tendinitis, which may coexist with acute strain injuries and the more chronic changes of osgood-Schlatter disease. Calcific tendinitis of the quadriceps has a characteristic radiographic appearance of whiskers on the anterosuperior patella. The suprapatellar, infrapatellar, and prepatellar bursae also may become inflamed with dysfunction of the quadriceps tendon. TreaTmenT Initial treatment of the pain and functional disability associated with osgood-Schlatter disease includes a combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and rest, with the patient avoiding activities that involve contraction of the quadriceps mechanism.

Buy 1mg tolterodine fast delivery

The association of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas with endometriosis and/or endometrial endometrioid carcinomas symptoms with twins order tolterodine 2mg without prescription, and the known response of endometriotic tissue to steroid hormones suggest that ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas may have similar risk factors. Clonality studies could also assist in this differential (see molecular features) but are rarely if ever needed. Grade 1 tumors and the well-differentiated areas of higher-grade tumors have invasive glandular, cribriform, and less often villoglandular patterns composed of round, oval, or tubular glands lined by stratified, mostly mucin-poor epithelial cells. Invasion is typically expansile or confluent, infiltrative invasion being uncommon. The cysts may contain luminal eosinophilic mucin (that may resemble colloid) or less often a basophilic secretion. A minor component of columnar mucinous cells is not uncommon and discounted for classification purposes. Morular or nonmorular squamous differentiation occurs in up to 50% of tumors, the former as rounded nests of small, immature but bland, often spindled, cells, the latter as foci of atypical to malignant squamous epithelium that may focally efface the associated glandular component. Right: the carcinoma is represented by small tubular glands and small clusters of cells infiltrating the stroma. The association between the two components may help establish the primary nature of the carcinoma. The neoplastic glands contain eosinophilic secretion, and their lining cells exhibit mild to moderate atypia. The cytologic atypia is less striking than would be expected in a serous papillary carcinoma. The squamous differentiation imparts a focally solid appearance in which some of the cells are spindled. An association of the carcinoma with an endometrioid adenofibroma or endometriosis can be a diagnostically helpful clue to its primary nature. The association of surface tumor with endometriosis aids its distinction from an implant of an endometrial endometrioid carcinoma if one is present. The stroma of endometrioid carcinomas varies from abundant to minimal; occasionally it may form intraglandular projections. Abundant stroma may be due to the presence of an associated adenofibroma from which the carcinoma has arisen. This tumor exhibits dirty necrosis which can cause confusion with metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma. Cysts are occasionally conspicuous and can result in confusion with cystic clear cell carcinoma. Glandular lining cells contain subnuclear (and sometimes supranuclear) glycogen vacuoles resembling the glandular cells of an early secretory endometrium. In high-grade tumors, sub- and supranuclear clearing may be less evident but still focally appreciable. Tumor cells with pale cytoplasm can suggest a lipid-rich Sertoli cell tumor (Chapter 16). The solid areas may have cells with pale nuclei and even nuclear grooves mimicking the appearance of a granulosa cell tumor. Some tumors have intraglandular buds of cells similar to those seen in the small nonvillous papillae of endometrial endometrioid carcinomas (Chapter 8). Unlike the papillae of serous carcinoma, the cells usually have low-grade nuclear features like those in the rest of the tumor. The prominent clear cells (right) may suggest clear cell carcinoma but a subtle hint of a subnuclear and supranuclear aspect to the clearing indicates an endometrioid nature. A whorl at the bottom center is suggestive of abortive squamous differentiation, a helpful finding in many cases of this type. These patterns of endometrial endometrioid carcinomas may occasionally occur in ovarian endometrioid carcinomas but are much less common than in the uterus. These cells may merge with obvious squamous cells, suggesting abortive squamous differentiation. The obvious endometrioid glandular differentiation (top) excludes that latter diagnosis. The predominant growth pattern is one of cords and trabeculae separated by hyalinized stroma, an appearance more common in endometrial endometrioid carcinomas (see Chapter 8). In contrast to a malignant mesodermal mixed tumor, the glandular and spindle cell component have low-grade nuclear features. Occasional otherwise typical endometrioid adenocarcinomas contain tumor cells with abundant oxyphilic cytoplasm. In these rare endometrioid adenocarcinomas, which usually have a cribriform pattern, most of the glandular lining cells bear cilia. Undifferentiated carcinomatous component (dedifferentiated carcinoma) (see Mixed Carcinomas). Immunostains are rarely necessary for diagnosis, but are helpful in distinguishing endometrioid carcinomas with sex cord-like patterns from a sex cord tumor (see below). Caveats: some high-grade endometrioid carcinomas are diffusely p53+; Cathro et al. Different genetic abnormalities, however, may reflect tumor heterogeneity rather than synchronous primary tumors. Recent studies have found common clonality between some synchronous ovarian and endometrial endometrioid carcinomas, Guerra et al. A variety of ovarian tumors other than endometrioid carcinomas may have an endometrioid-like glandular pattern (Appendix 2). As noted above, molecular studies may also aid in this assessment but are rarely needed. The major prognostic determinant in such cases is the grade and depth of myoinvasion by the endometrial tumor. These tumors typically have glands that architecturally resemble those of endometrioid carcinomas but are lined by cells with the amphophilic cytoplasm that is typical of most endocervical adenocarcinomas. Extragenital metastatic carcinomas, particularly those arising in the intestine (Chapter 18). Brenner tumors lack the typical endometrioid glands of adenofibromas and the morules of the latter often show focal unequivocal squamous differentiation. However, the epithelial elements of endometrioid carcinomas can rarely be inhibin+, and any non-neoplastic luteinized stromal cells will be inhibin+ and/or calretinin+. In such cases, the patient is usually older and features diagnostic of endometrioid carcinoma are also present. Additionally, in most such cases the two components are usually distinct rather than intermixed. Other characteristic patterns of endometrioid carcinomas or wolffian tumors are usually present. Seventy-five percent occur in the sixth to eighth decades; rare tumors occur in those <40 years of age. Typical large neoplasm with fleshy solid tissue and focal cysts seen on the cut surface. Endometrioid-type glands are separated by a malignant spindle cell stroma with nonspecific features. Cords and clusters of malignant epithelial cells are separated by a malignant stroma without evidence of specific differentiation. The various epithelial and sarcomatous components and their relative proportions can produce a highly variable appearance. Immunostains may be helpful in distinguishing sarcomatoid carcinoma from true sarcoma but are rarely needed. The carcinomatous component is most commonly serous, endometrioid, or undifferentiated; glandular neoplasia that is difficult to classify as to cell type is not uncommon. Homologous tumors account for half the cases and typically have a high-grade, predominantly spindle cell, nonspecific sarcomatous component. Prominent foci of malignant cartilage are intimately intermixed with nonspecific malignant epithelial and sarcomatous elements which show focal gland formation. Such tumors are otherwise typical mucinous, serous, or clear cell carcinomas that contain a Differential diagnosis sarcomatous nodule (rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, or leiomyosarcoma). Features favoring or indicating immature teratoma include an age <30 years, elements derived from all three germ layers, a predominant component of immature neuroectodermal tissue, an embryonal (vs carcinomatous) epithelial component, and immature or mature (vs malignant) cartilage.

Order tolterodine 1mg with mastercard

Adenoid basal carcinoma of the cervix: A unique morphological evolution with cell cycle correlates translational medicine buy 2 mg tolterodine otc. The origin and molecular characterization of adenoid basal carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Terminology of endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: Results of a workshop sponsored by the College of American pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A review of 226 cases with emphasis on patterns of growth and immunohistochemical features. Prognostic factors in neuroendocrine small cell cervical carcinoma: A multivariate analysis. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Cervical carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation: A report of 28 cases with immunohistochemical analysis and molecular genetic evidence of 157. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Review of a series of cases and correlation with outcome. Small-cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the cervix: A clinicopathologic, ultrastructural, and immunocytochemical study of 15 cases. Mixed small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: Prognostic impact of focal neuroendocrine differentiation but not of Ki-67 labeling index. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix: A histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: the role of multimodality therapy in early-stage disease. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Prognostic factors and survival advantage with platinum chemotherapy. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Detection of human papillomavirus in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a study of 12 cases. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix associated with intestinal variant (of) invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix with cytogenetic analysis by comparative genomic hybridization: A case study. Spectrum of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the uterine cervix, including histopathologic features, terminology, immunohistochemical profile, and clinical outcomes in a series of 50 cases from a single institution in India. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: A clinicopathologic study of six cases. Cervical carcinoma with divergent neuroendocrine and gastrointestinal differentiation. Monoclonality of composite large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and invasive intestinal-type mucinous adenocarcinoma of the cervix: A case study. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma Albores-Saavedra J, Martinez-Benitez B, Luevano E. Compact, densely cellular nests of degenerating endometrial stromal cells with scanty cytoplasm and small, sometimes spindled, hyperchromatic nuclei are characteristic of menstrual endometrium, and have been mistaken for small cell carcinoma. Other typical findings include neutrophils, nuclear debris, syncytial papillary change (see corresponding heading below), and fibrin thrombi. Features distinguishing menstrual changes from abnormalities include the fragmented and degenerative appearance of the epithelium and stroma, common residual secretory changes, and the absence of nuclear atypicality and mitotic activity other than that acceptable for a reactive process. Menstrual endometrium can rarely be found within myometrial vessels, potentially mimicking intravascular carcinoma. Left and center: Note fragmented glands, compacted aggregates of degenerating stromal cells, neutrophils, and blood. Cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblaste a Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid Endometrioid or squamous cell Endometrioid Endometrioid Villoglandular endometrioid or serous Mucinous Mucinous Serous Serous or clear cell Serous or clear cell Clear cell Small cell Undifferentiated Undifferentiated Undifferentiated or signet-ring cell Undifferentiated Undifferentiated Squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated Undifferentiated or giant cell Telescoping is more likely to be confused with hyperplasia than carcinoma. Similar changes may be found within fragments of endocervical polyps procured during an endometrial sampling. Cervical microglandular hyperplasia or even crowded aggregates of endocervical glands with or without squamous metaplasia can also be associated with diagnostic problems if the fragments are not recognized as endocervical in origin. This finding in biopsy or curettage fragments can suggest an endometrial stromal neoplasm or a small cell carcinoma. The scant tissue, atrophic appearance, and mitotic inactivity facilitate the diagnosis. The surface epithelium in an atrophic endometrium may show nuclear atypia and/or enlargement that may cause concern for intraepithelial serous carcinoma but in the former severe nuclear atypia and mitotic activity are absent. There is often eosinophilic cytoplasm, a subtle distinction from most cases of minimal volume (intraepithelial) serous carcinoma. Furthermore, atypia in the setting of atrophy would demonstrate a wild-type p53 staining pattern and low proliferative index by Ki-67, whereas serous carcinoma would show an abnormal p53 pattern (diffuse overexpression or complete loss) with increased proliferation. A sampling from an atrophic endometrium often yields only scanty strips of endometrial surface epithelium. Left: Focal nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia are seen in the epithelial fragment at the top of the figure. Wild-type p53 expression (center panel) and very focal ki-67 staining (right panel) indicate a non-neoplastic process. This appearance can be misinterpreted as a complex hyperplasia or carcinoma, especially if the glands are proliferative with mitotic activity. Strips of endometrial surface epithelium can become coiled and compacted, producing a pseudopapillary pattern. This finding is often associated with an atrophic endometrium, but its appearance can be misconstrued as papillary hyperplasia or carcinoma. Postcurettage epithelial atypia, which may be striking, is typically confined to the surface epithelium and superficial glands. The reactive cells may have enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with occasionally prominent nucleoli and sometimes a hobnail appearance (Table 7. The characteristic eosinophilic cytoplasm and focal stromal breakdown are also seen. Small tufts of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm are intermixed with aggregates of stroma showing breakdown. Glandular and surface epithelia, including those of polyps (especially those with papillary proliferations, see corresponding heading), may be involved. As metaplasias often reflect unopposed estrogen stimulation, metaplastic glands may be synchronously hyperplastic or associated with a synchronous typical endometrial hyperplasia or adenocarcinoma. Other etiologic factors are considered under the specific types of metaplasia (including syncytial papillary change) in the following sections. It is typically associated with postovulatory or anovulatory menstrual bleeding but may occur within or on the surface of an infarcted polyp. The appearance varies with its extent, the degree of its syncytial and papillary features, and the prominence of the associated stromal breakdown. The endometrial surface epithelium and less commonly the superficial glands are involved. This example shows a predominantly plaque-like proliferation with only limited papillarity. Center: Stroma free papillae are composed of syncytial eosinophilic cells with bland nuclear features; nuclear debris is also present. The cells usually have bland nuclear features but occasionally show reactive atypia, a hobnail appearance, and rare mitoses. Other menses-related changes (see separate heading) are often present, including neutrophils, nuclear debris, small nests of degenerating endometrial stromal cells, and thrombosed sinusoids. The papillarity, occasional cytologic atypia, mitoses, and p16 positivity may suggest a papillary carcinoma, especially serous carcinoma. The immunoprofile of morular cells differs from that of typical squamous cells (see below), likely reflecting their immature nature. Morular metaplasia is often related to unopposed estrogen, or less commonly, progestin treatment, but may be idiopathic. Morules are composed of immature, round to spindled, epithelial cells, with indistinct cell borders and bland nuclei that are occasionally optically clear. As noted above, morular metaplasia most commonly reflects unopposed estrogen stimulation, being most frequent within endometrial hyperplasia and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Chapter 8) as well as atypical polypoid adenomyomas (Chapter 9).

Syndromes

- Is it the first time you have had tenesmus?

- The surgeon will loosen skin, fat, and muscle from this area and then tunnel this tissue under your skin to the breast area. This tissue will be used to create your new breast. Blood vessels will remain connected to the area from where the tissue was taken.

- Abdominal pain that does not go away

- Adrenocortical hyperplasia

- Loperamide to treat diarrhea

- Symptoms that last more than 3 weeks

- Fatigue, reduced activity tolerance

- "Acts up" with intense tantrums

- Painful menstruation

- Repeated urine cultures

Buy tolterodine 4mg amex

In this setting treatments tolterodine 4 mg cheap, an astute clinician should advise the patient to call immediately if a rash appears, because acute herpes zoster is a possibility. In this case, pain in the distribution of the thoracic nerve roots without an associated rash is called zoster sine herpete and is, by necessity, a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore, other causes of thoracic and subcostal pain must be ruled out before this diagnosis is invoked. The joint is often traumatized during accelerationdeceleration injuries and blunt trauma to the chest; with severe trauma, the joint may subluxate or dislocate. The joint is also subject to invasion by tumor from primary malignant disease, including lung cancer, or from metastatic disease. Pain emanating from the costovertebral joint can mimic pain of pulmonary or cardiac origin. Because ankylosing spondylitis commonly affects both the costovertebral joint and the sacroiliac joint, many patients assume a stooped posture, which should alert the clinician to the possibility of this disease as the cause of costovertebral joint pain. A, Photograph of the lateral aspect of the macerated thoracic spine of a spondylitic cadaver demonstrates extensive bony ankylosis (arrows) of the head of the ribs (R) and vertebral bodies. B, Transaxial computed tomography scan of a thoracic vertebra in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis reveals bone erosions and partial ankylosis (arrowhead) of the costovertebral joints on one side. Laboratory evaluation for collagen vascular disease and other joint diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis, is indicated for patients with costovertebral joint pain, especially if other joints are involved. Magnetic resonance imaging of the joints is indicated if joint instability or occult mass is suspected or to elucidate the cause of the pain further. If trauma has occurred, costovertebral joint syndrome may coexist with fractured ribs or fractures of the spine or sternum itself, injuries that can be missed on plain radiographs and may require radionuclide bone scanning for proper identification. Neuropathic pain involving the chest wall may also be confused or coexist with costovertebral joint syndrome. Diseases of the structures of the mediastinum are possible and can be difficult to diagnose. Use of an elastic rib belt may provide symptomatic relief and protect the costovertebral joints from additional trauma. Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and short tau inversion recovery (B) magnetic resonance images show an expansile, destructive mass replacing a lumbar vertebra, with remodeling of the posterior margin and an epidural component (arrow). Axial computed tomography scan (C) shows the lesion involving the pedicle and transverse process, with a significant intraspinal component. This complication can be greatly reduced with strict attention to accurate needle placement. Ne ck of rib Clinical Pearls Patients with pain emanating from the costovertebral joint may believe that they are suffering from pneumonia or having a heart attack. CompliCaTionS and piTfallS Because many pathologic processes can mimic the pain of costovertebral joint syndrome, the clinician must carefully rule out underlying diseases of the lung, heart, and structures of the spine and mediastinum. Although the reason that this painful condition occurs in some patients but not in others is unknown, postherpetic neuralgia is more common in older individuals and appears to occur more frequently after acute herpes zoster involving the trigeminal nerve, as opposed to the thoracic dermatomes. Conditions that cause vulnerable nerve syndrome, such as diabetes, may also predispose patients to develop postherpetic neuralgia. Pain specialists agree that aggressive treatment of acute herpes zoster can help prevent postherpetic neuralgia. In most patients, the sensory abnormalities and pain resolve as the skin lesions heal. Sharp, shooting neuritic pain may be superimposed on the constant dysesthetic pain. Some patients suffering from postherpetic neuralgia also note a burning component, reminiscent of reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Such testing includes basic laboratory screening, rectal examination, mammography, and testing for collagen vascular diseases and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Skin biopsy may confirm the presence of previous infection with herpes zoster if the history is in question. SignS and SympTomS As the lesions of acute herpes zoster heal, the crust falls away, leaving pink scars that gradually become hypopigmented and atrophic. This evaluation also allows early recognition of changes in clinical status that may presage the development of complications, including myelitis or dissemination of the disease. Intrathoracic and intraabdominal disorders may also mimic the pain of acute herpes zoster involving the thoracic dermatomes. For pain in the distribution of the first division of the trigeminal nerve, the clinician must exclude diseases of the eye, ear, nose, and throat, as well as intracranial disorders. After several weeks of treatment, antidepressants may exert a mood-elevating effect that is desirable in some patients. These drugs may cause urinary retention and constipation that may mistakenly be attributed to herpes zoster myelitis. Nerve Block Neural blockade with local anesthetic and steroid through either epidural nerve block or blockade of the sympathetic nerves subserving the painful area is a reasonable next step if the aforementioned pharmacologic modalities fail to control the pain of postherpetic neuralgia. Although the exact mechanism of pain relief is unknown, it may be related to modulation of pain transmission at the spinal cord level. In general, neurodestructive procedures have a very low success rate and should be used only after all other treatments have failed, if at all. Opioid Analgesics opioid analgesics have a limited role in the management of postherpetic neuralgia and may do more harm than good. Because many patients suffering from postherpetic neuralgia are older or have severe multisystem disease, close monitoring for the potential side effects of opioid analgesics. Adjunctive Treatments the application of ice packs to the affected area may provide relief in some patients. The application of heat increases pain in most patients, presumably because of increased conduction of small fibers; however, it is beneficial in an occasional patient and may be worth trying if the application of cold is ineffective. The favorable risk-to-benefit ratio of all these modalities makes them reasonable alternatives for patients who cannot or will not undergo sympathetic neural blockade or who cannot tolerate pharmacologic interventions. The topical application of capsaicin may be beneficial in some patients suffering from postherpetic neuralgia; however, this substance tends to burn when applied, thus limiting its usefulness. TreaTmenT Ideally, rapid and aggressive treatment of acute herpes zoster is instituted in every patient, because most pain specialists believe that the earlier treatment is initiated, the less likely postherpetic neuralgia will be to develop. This approach is especially important in older individuals, who are at greatest risk for postherpetic neuralgia. Analgesics the anticonvulsant gabapentin is first-line treatment for the pain of postherpetic neuralgia. Treatment with gabapentin should begin early in the course of the disease, and this drug may be used concurrently with neural blockade, opioid analgesics, and other analgesics, including antidepressants, if care is taken to avoid central nervous system side effects. Gabapentin is started at a dose of 300 mg at bedtime and is titrated upward in 300-mg increments to a maximum of 3600 mg/day in divided doses, as side effects allow. Carbamazepine should be considered in patients suffering from severe neuritic pain in whom nerve blocks and gabapentin fail to provide relief. If this drug is used, rigid monitoring of hematologic parameters is indicated, especially in patients receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Phenytoin may also be beneficial to treat neuritic pain, but it should not be used in patients with lymphoma; the drug may induce a pseudolymphoma-like state that is difficult to distinguish from actual lymphoma. Antidepressants Antidepressants may be useful adjuncts in the initial treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. In addition, antidepressants may be valuable in CompliCaTionS and piTfallS Although no specific complications are associated with postherpetic neuralgia itself, the consequences of the unremitting pain can be devastating. Failure to treat the pain of postherpetic neuralgia and the associated symptoms of sleep disturbance and depression aggressively can result in suicide. If postherpetic neuralgia develops, the aggressive treatment outlined here, with special attention to the insidious onset of severe depression, should be undertaken. If serious depression occurs, hospitalization with suicide precautions is mandatory. In osteoporotic patients or in those with primary tumors or metastatic disease involving the thoracic vertebrae, fracture may occur with coughing (tussive fractures) or spontaneously.

Proven 4 mg tolterodine

Markers of proliferative activity are predictors of patient outcome for low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma but not papillary serous carcinoma of endometrium treatment questionnaire discount 4mg tolterodine visa. Endometrial cancer patients have a significant risk of harboring isolated tumor cells in histologically negative lymph nodes. Microsatellite instability in endometrioid type endometrial adenocarcinoma is associated with poor prognostic indicators. Progesterone receptor negativity is an independent risk factor for relapse in patients with early stage endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Programmed death ligand 1 expression among 700 consecutive endometrial cancers: Strong association with mismatch repair protein deficiency. The impact of androgen receptor expression on endometrial carcinoma recurrence and survival. A panel of immunohistochemical stains, including carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, and estrogen receptor, aids the distinction between primary endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinomas. Immunohistochemical expression of core 2 1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase 1 (C2GnT1) in endometrioid-type endometrial carcinoma: A novel potential prognostic factor. Immunophenotypic diversity of endometrial adenocarcinomas: implications for differential diagnosis. Clinically occult tubal and ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas presenting in uterine samples: Diagnostic pitfalls and clues to improve recognition of tumor origin. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: A study on 108 cases with emphasis on the prognostic significance of associated endometrioid carcinoma, absence of invasion, and concomitant ovarian carcinoma. Serous endometrial cancers that mimic endometrioid adenocarcinoma: A clinicopathologic study of a group of problematic cases. An updated clinicopathologic study of early-stage uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Strategies for distinguishing low-grade endometrioid and serous carcinomas of endometrium. Peritoneal cytology: A risk factor of recurrence for non-endometrioid endometrial cancer. Clinical significance of positive pelvic washings in uterine papillary serous carcinoma confined to an endometrial polyp. Endometrial serous carcinoma with clear-cell change: Frequency and immunohistochemical analysis. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: A highly malignant form of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Serous adenocarcinoma of the uterus presenting as paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Radiation-associated endometrial cancers are prognostically unfavorable tumors: A clinicopathologic comparison with 527 sporadic endometrial cancers. Extent of lymphovascular space invasion may predict lymph node metastasis in uterine serous carcinoma. Clinical and pathological characteristics of serous carcinoma confined to the endometrium: A multi-institutional study. Transtubal spread of serous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: An underrecognized mechanism of metastasis. Significance of lymphovascular space invasion in uterine serous carcinoma: What matters more; extent or presence Serous endometrial carcinoma arising in an endometrial polyp: A proposal for modification of terminology. Coexisting intraepithelial serous carcinomas of the endometrium and fallopian tube: Frequency and potential significance. Endometrial glandular dysplasia with frequent p53 gene mutation: genetic evidence supporting its precancer nature for endometrial serous carcinoma. Uterine serous carcinoma and endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma arising in endometrial polyps: Report of 5 cases including 2 associated with tamoxifen therapy. Serous papillary carcinoma of the endometrium arising from endometrial polyps: A clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. High-grade endometrial carcinoma: Serous and grade 3 endometrioid carcinomas have different immunophenotypes and outcomes. Coordinate patterns of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and Wilms tumor 1 expression in the histopathologic distinction of ovarian from endometrial serous adenocarcinomas. Serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma arising in adenomyosis: A report of 5 cases. The frequency of p53, K-ras mutations, and microsatellite instability differs in uterine endometrioid and serous carcinoma. Increased p16 expression in high-grade serous and undifferentiated carcinoma compared with other morphologic types of ovarian carcinoma. Utility of p16 expression for distinction of uterine serous carcinomas from endometrial endometrioid and endocervical adenocarcinomas. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium: Evaluation of prognostic parameters in a multi-institutional cohort of 165 cases. Mucinous and clear cell adenocarcinomas of the endometrium in patients receiving antiestrogens (tamoxifen) and gestagens. Diagnostic utility of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1beta immunoreactivity in endometrial carcinomas: Lack of specificity for endometrial clear cell carcinoma. Morphologic and other clinicopathologic features of endometrial clear cell carcinoma: A comprehensive analysis of 50 rigorously classified cases. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Molecular alterations in endometrial and ovarian clear cell carcinomas: clinical impacts of telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation. Morphologic and immunohistochemical study of clear cell carcinoma of the uterine endometrium and 236. Clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium is characterized by a distinctive profile of p53, Ki-67, estrogen, and progesterone receptor expression. Somatic mutation profiles of clear cell endometrial tumors revealed by whole exome and targeted gene sequencing. Clear cell carcinoma of the female genital tract (not everything is as clear as it seems). Immunohistochemical detection of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 in ovarian and endometrial clear-cell adenocarcinomas and nonneoplastic endometrium. Comparison of morphologic and immunohistochemical features of cervical microglandular hyperplasia with low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Atypical mucinous glandular proliferations in endometrials samplings: follow-up and other clinicopathological findings in 41 cases. Proliferative mucinous lesions of the endometrium: Analysis of existing criteria for diagnosing carcinoma in biopsies and curettings. Endometrial carcinomas with significant mucinous differentiation associated with higher frequency of K-ras mutations: A morphologic and molecular correlation study. Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with intestinal differentiation: A case report. Endometrial adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells: Report of two cases of an extremely rare phenomenon. Immunohistochemical differences between mucinous and microglandular adenocarcinomas of the endometrium and benign endocervical epithelium. Low-grade mucinous adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: A rare and deceptively bland form of endometrial carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging findings and prognosis of gastric-type mucinous adenocarcinoma (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma or adenoma malignum) of the uterine corpus: Two case reports. Mucinous endometrial epithelial proliferations: A morphologic spectrum of changes with diverse clinical significance. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium: Clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics. Squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium: A report of eight cases and a review of the literature. P16, p14, cyclin D1, and steroid hormone receptor expression and human papillomaviruses analysis in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the endometrium. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma in situ with intraepithelial extension to the upper genital tract and invasion of tubes and ovaries: Report of a case with human papilloma virus analysis.

Cheap tolterodine 1 mg without a prescription

The needle is then removed medications known to cause weight gain purchase cheap tolterodine, and a sterile pressure dressing and ice pack are placed at the injection site. Lateral radiograph (A) demonstrates a soft-tissue mass on the dorsum of the wrist. Ultrasound (B) in a second patient shows the typical anechoic cystic appearance of a ganglion. Sagittal T1-weighted (C) and axial T2-weighted fat-saturation (D) magnetic resonance images through the distal carpal row in a third patient show a circumscribed cystic mass. Axial T1-weighted (A), axial T2-weighted (B), and coronal T1-weighted (C) magnetic resonance images demonstrate a large mass surrounding the index finger. Care must be taken to avoid injecting directly into tendons that may already be inflamed from irritation caused by rubbing of the ganglion against the tendon. Trauma is usually caused by repetitive motion or pressure on the tendon as it passes over these bony prominences. Frequently, nodules develop on the tendon, and they can often be palpated when the patient flexes and extends the thumb. Such nodules may catch in the tendon sheath and produce a triggering phenomenon that causes the thumb to catch or lock. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hand is indicated if first metacarpal joint instability is suspected or if the diagnosis of trigger finger is in question. The pain of trigger thumb is constant and is made worse with active pinching of the thumb. Sleep disturbance is common, and patients often awaken to find that the thumb has become locked in a flexed position. Many patients with trigger thumb experience a creaking sensation with flexion and extension of the thumb. Range of motion of the thumb may be decreased because of pain, and a triggering phenomenon may be present. TreaTmenT Initial treatment of the pain and functional disability associated with trigger thumb includes a combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and physical therapy. If these treatments fail, the following injection technique is a reasonable next step. After sterile preparation of the skin overlying the affected tendon, the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb is identified. Using strict aseptic technique, at a point just proximal to the joint, the clinician inserts a 1-inch, 25-gauge needle at a 45-degree angle parallel to the affected tendon through the skin and into the subcutaneous tissue overlying the tendon. The tendon may rupture if it is injected directly, so a needle position outside the tendon should be confirmed before proceeding with the injection. Further, the radial artery and superficial branch of the radial nerve are susceptible to damage if the needle is placed too far medially. Another complication of injection is infection, although it should be exceedingly rare if strict aseptic technique is followed. A, the initial radiograph outlines small osseous fragments adjacent to the first metacarpophalangeal joint (arrow). B, A radiograph obtained during radial stress reveals subluxation of the phalanx on the metacarpal bone. The injection technique is safe if careful attention is paid to the clinically relevant anatomy, including the radial artery and the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Trauma is usually the result of repetitive motion or pressure on the tendon as it passes over these bony prominences. If the inflammation and swelling become chronic, the tendon sheath may thicken, resulting in constriction. Frequently, nodules develop on the tendon, and they can often be palpated when the patient flexes and extends the fingers. Such nodules may catch in the tendon sheath as they pass under a restraining tendon pulley, thus producing a triggering phenomenon that causes the finger to catch or lock. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hand is indicated if joint instability or some other abnormality is suspected. Sleep disturbance is common, and patients often awaken to find that the finger has become locked in a flexed position. Many patients with trigger finger experience a creaking sensation with flexion and extension of the fingers. Range of motion of the fingers may be decreased because of pain, and a triggering phenomenon may be noted. A catching tendon sign may also be elicited by having the patient clench the affected hand for 30 seconds and then relax but not open the hand. After sterile preparation of the skin overlying the affected tendon, the head of the metacarpal beneath the tendon is identified. Using strict aseptic technique, at a point just proximal to the joint, a 1-inch, 25-gauge needle at a 45-degree angle parallel to the affected tendon through the skin and into the subcutaneous tissue overlying the tendon. Little resistance to injection should be felt; if resistance is encountered, the needle is probably in the tendon and should be withdrawn until the injection can be accomplished without significant resistance. Surgical treatment should be considered for patients who fail to respond to the aforementioned treatment modalities. CompliCaTionS and piTfallS Failure to treat trigger finger early adequately in its course can result in permanent pain and functional disability because of continued trauma to the tendon and tendon sheath. The major complications associated with injection are related to trauma to the inflamed and previously damaged tendon. Another complication of injection is infection, although it should be exceedingly rare if strict aseptic technique is used, along with universal precautions to minimize any risk to the operator. A, In this 55-year-old woman with a 2-year history of pain and gradual swelling of the fingers, a soft tissue mass (arrow) can be identified at one distal interphalangeal joint. Underlying inflammatory osteoarthritis of the articulations is evident, and this combination of findings would suggest that the mass is a mucous cyst. However, biopsy of the affected joint demonstrated a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath. Clinical Pearls the injection technique described is extremely effective in the treatment of pain secondary to trigger finger. A hand splint to protect the fingers may also help relieve the symptoms of trigger finger. These bones serve to decrease the friction and pressure of the flexor tendon as it passes in proximity to a joint. When grasping something, the patient often feels that he or she has a foreign body embedded in the affected digit. The pain of sesamoiditis worsens with repeated flexion and extension of the affected digit. When the thumb is affected, it is usually on the radial side, where the condyle of the adjacent metacarpal is less obtrusive. Patients suffering from psoriatic arthritis may have a higher incidence of sesamoiditis of the hand. SignS and SympTomS on physical examination, pain can be reproduced by pressure on the sesamoid bone. In patients with sesamoiditis, the tender area moves with the flexor tendon when the patient actively flexes the thumb or finger, whereas with occult bony disease of the phalanges, the tender area remains over the pathologic area. With acute trauma to the sesamoid, ecchymosis over the flexor surface of the affected digit may be present. Radionuclide bone scanning may be useful to identify stress fractures of the thumb and fingers or sesamoid bones that may be missed on plain radiographs of the hand. If the patient does not respond to these conservative measures, a trial of injection therapy with local anesthetic and steroid is a reasonable next step. To perform injection of the sesamoid bone, the patient is placed in the supine position with the palmar surface of the hand exposed. The needle is carefully advanced through the palmar surface of the 181 figure 56-1 Sesamoiditis is characterized by tenderness and pain over the flexor aspect of the thumb. A, Startling osseous excrescences (arrows) around the metacarpal heads are associated with soft tissue swelling, joint space narrowing, and bony erosion and proliferation in the phalanges. B, At the first metacarpophalangeal joint, irregular bone formation in the metacarpal head, proximal phalanx, and adjacent sesamoid (arrow) can be seen.

Purchase 1 mg tolterodine free shipping

They are the only germ cell tumor seen with any frequency after menopause treatment 5th metacarpal fracture tolterodine 1 mg with mastercard, some tumors not being detected until years after its onset. The patients may have the typical symptoms and signs of a benign ovarian tumor, but up to 60% are asymptomatic. The radiologic presence of teeth and calcification may suggest or indicate the diagnosis. A sudden rupture may cause an acute abdomen, whereas a slow leak may lead to a granulomatous peritonitis that intraoperatively can mimic metastatic carcinoma. The tumors (unlike immature teratomas) are predominantly cystic with usually only one locule but occasionally two or more. They vary in size but are uncommonly >8 cm and on average are about half the size of immature teratomas. Grumous material including hair (right) has been removed from the cystic neoplasm, which exhibits a Rokitansky protuberance (left). Respiratory type epithelium and salivary gland type tissue, common within these neoplasms, are evident. Teeth occur in one-third of the cases, either in the cyst wall or cavity, occasionally within a rudimentary mandible or maxilla. Bone, cartilage, mucinous cysts, adipose tissue, thyroid, and soft brain tissue are occasionally visible grossly. Adult-type tissues, usually representing all three germ layers, sometimes arranged in an organoid fashion, are seen. Foci of fetal-type tissues are encountered in many otherwise typical cases and have no prognostic Microscopic features (figs. Ectodermal derivatives predominate in almost all the tumors, and include keratinized epidermis, sebaceous and sweat glands, hair follicles, and neuroectodermal elements (glial and peripheral nervous tissue, ependymal tubules, cerebrum, cerebellum, and choroid plexus). Rare foci of immature neuroectodermal tissues are allowable in an otherwise typical dermoid cyst (Yanai-Inbar and Scully). Endodermal derivatives include respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelium and thyroid and salivary gland tissue. Occasional to rare tissues include retina, pancreas, thymus, adrenal, pituitary, kidney, lung, breast, prostate, and seminal vesicle. Typical cerebellar tissue as shown here can be misinterpreted as immature elements. These are relatively common in such tumors and should not lead to a diagnosis of immature teratoma. Left: Beneath of a nodule of hyaline cartilage is a proliferation of anastomosing vascular channels with open lumina. The neuroectodermal elements can incite a florid vascular proliferation identical to that described in immature teratomas and their implants. The latter abutted cranially derived tissues, especially scalp-like skin and glial tissue. The former diagnosis should be made cautiously when the gross features are those of a dermoid. The sieve-like pattern may not be recognized as diagnostic and considered nonspecific fat necrosis. Mature implants (usually peritoneal glial implants, as noted below in immature teratomas) are found at presentation in some cases. The macroscopic appearance is similar to that of immature teratoma except that soft, necrotic, and hemorrhage foci are much less common. The tumors are composed exclusively by mature tissues representing all three germ layers; mature glial tissue may be the predominant element. All of the reported (well-sampled) tumors, including those with mature implants, have been associated with a benign course. The differential diagnosis with immature teratomas is discussed under the latter heading. A homunculus should be distinguished from the fetus-in-fetu, a parasitic monozygotic twin that develops within the upper retroperitoneal space of its partner. Most cases of fetus-in-fetu have occurred in infants <1 year of age, and no ovarian examples have been reported. Immature teratomas are occasionally preceded by an ipsilateral dermoid cyst resected months to years previously. The risk of an immature teratoma in such patients may be increased if the dermoid cysts are bilateral, multiple, or associated with rupture (Yanai-Inbar and Scully). A third of patients have extraovarian spread at presentation, usually in the form of peritoneal implants (see below), less commonly nodal metastases. The median diameter is 16 cm and the typically predominantly solid cut surface is fleshy, gray to pink, often with focal hemorrhage and necrosis. The sine qua non is the presence of embryonic-appearing (not simply immature) tissue that is usually predominantly neuroectodermal, specifically neuroepithelial rosettes and tubules and cellular foci of mitotically active glia. Other embryonal or immature tissues are commonly present and include epithelium of various types (ectodermal and endodermal, including hepatic) and mesenchymal elements, such as cartilage and skeletal muscle. One otherwise typical immature teratoma was composed of a predominant component of choroid plexus. An uncommon finding is a striking proliferation of mostly small, thin-walled, closely packed vessels that form trabeculae or small nests, a finding that may incorrectly suggest immature elements or a vascular neoplasm. The sectioned surface of a large mass shows a variegated solid pattern with scattered small cysts. Many immature neuroectodermal tubules are seen in addition to hypercellular glial tissue. This high-grade (grade 3) example shows numerous neuroectodermal tubules, which focally coalesce. A higher-power view shows primitive neuroepithelium and intensely cellular intervening stroma. Primitive neuroectodermal tubules are associated with a primitive mesenchyme (center). A high-power view of several primitive neuroectodermal tubules shows the typical stratified darkly staining neuroepithelium. The nodules are characteristically rounded, well-circumscribed and oval as shown here. The glial foci in this illustration are more irregular in size and shape than is usual and are seen surrounding foci of endometriosis. A typical high-power appearance of nodules, which may occasionally be slightly hypercellular as seen here. Primary and metastatic immature teratomas are graded by the aggregate amount of immature neural tissue within them: <1 low-power-field [lpf] in any 1 slide = grade 1; 2 or 3 lpfs in any 1 slide = grade 2; and 4 lpfs in any 1 slide = grade 3. Generous sampling of implants is essential as immature and mature implants may coexist. Similarly, when a dermoid is associated with an immature teratoma, both components are usually apparent on gross examination. These tumors typically occur in older women, only rarely contain neuroectodermal elements, and contain foci of obvious carcinoma. Almost all patients with peritoneal gliomatosis have a benign clinical course, even without postoperative treatment. Awareness of its distinctive features will aid its recognition when seen at extragonadal sites. This low-power view shows the characteristic lobular growth with darkly staining embryoid bodies sitting within a loose edematous stroma. An embryoid body shows the primitive epithelium of the germ disc (center) with thin yolk sac epithelium superior to the disc and a large cystic cavity recapitulating the amniotic cavity inferiorly. The usually bulky tumors are often soft and reddish-brown, but may have other appearances. Low-power examination often shows a lobular architecture with embryoid bodies scattered, often somewhat evenly, within a background of edematous to myxoid connective tissue. Perfectly formed embryoid bodies are rare but imperfectly formed or fragmented examples are more common and recognizable by an intimate association of germ disc and yolk sac epithelium.