Buy zebeta 2.5 mg

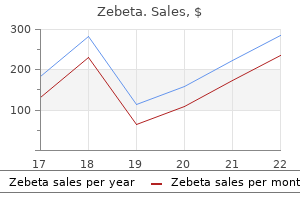

The first and most critical step in staging is endoscopic resection of the lesion with pathologic evaluation of the depth of invasion and risk factors for node metastases including size greater than 2 cm zolpidem arrhythmia buy 2.5mg zebeta free shipping, poor differentiation, and lymphovascular invasion. There is some evidence that low-risk submucosal lesions may be treated endoscopically, particularly in patients at increased risk for esophagectomy. Reported rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma found in the final pathology around 40% made any other approach prohibitively risky in the surgical candidate. They found that those with invasive esophageal cancer on final pathology underwent more procedures to attempt eradication on average (6. Following esophagectomy at specialized high-volume centers, the 5-year survival rates approach 90%. There have been several paradigm shifts in the way that we think about and treat the disease. This trend is sure to continue and our current practices will someday be historic, as interventions become increasingly efficacious and less invasive. As for now, treatment of Barrett esophagus remains steeped in controversy, complex, and highly challenging across its spectrum and highlights the importance of a multispecialty and modality approach to these patients. Effect of segment length on risk for neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett esophagus. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Depth of submucosal invasion does not predict lymph node metastasis and survival of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Are endoscopic therapies appropriate for superficial submucosal esophageal adenocarcinoma Reduced esophageal cancer incidence in statin users, particularly with cyclo-oxygenase inhibition. Mixed reflux of gastric and duodenal juices is more harmful to the esophagus than gastric juice alone. Duodenogastric reflux potentiates the injurious effects of gastroesophageal reflux. Alkaline gastroesophageal reflux: assessment by ambulatory esophageal aspiration and pH monitoring. Comparative effectiveness of esophagectomy versus endoscopic treatment for esophageal high-grade dysplasia. Esophagectomy for failed endoscopic therapy in patients with high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma. This major procedure clearly removes the pathology, as well as the whole Barrett segment, but at a cost of morbidity and mortality. Thus for every patient the role and value of these treatments must be weighed against the impact of the treatment on the individual from a cancer prevention perspective, the impact on quality of life both after treatment and in the long term, and the cost implications to the community. The optimal ablative therapy would completely eliminate the mucosa to the submucosa, in a single session, with very few side effects, and offer the patient a lifetime guarantee of no recurrence following complete squamous re-epithelialization of the treated segment. The indications for Barrett ablation, along with the techniques and their outcomes, will be described in this chapter. Chapter 31 has addressed the issues related to the definition of Barrett intestinal metaplasia that, when present, will lead to endoscopic surveillance. If there is a diagnosis of dysplasia at endoscopy, the management implications change for the patient and the clinician. The use of mucosal ablation for low-grade dysplasia can be considered under strict pathologic and clinical guidelines but should not be used in patients with nondysplastic intestinal metaplasia. All patients who have had endoscopic therapy for Barrett dysplasia require long-term acid suppression therapy and careful endoscopic follow-up. In the future, for ablation to be considered, there will need to be a number of factors better defined. The larger specimens offered to the pathologist may reduce the variation of interpretation that can occur when small sample biopsies are assessed among multiple pathologists. Endoscopic Mucosal Resection Technique Single or multiple applications may be required depending upon the area of abnormal mucosa. This technique allows the suction of mucosa to form a pseudopolyp, the base of which is "ligated" with a band. A simple band and snare technique, with or without submucosal injection, can also be performed. The advantage is the ability to remove larger lesions en bloc in the plane between the submucosa and the muscularis propria. The lesion is outlined with a normal margin using cautery and is elevated using a submucosal fluid injection. An Endoknife is used to cut and coagulate the mucosa and submucosa, with Endograspers used for localized bleeding. The selection criteria were visible lesion, multiple lesions, and lesions larger than 15 mm or poorly lifting with submucosal injection. There were two patients who had a delayed hemorrhage and three with perforation, all treated endoscopically. The stricture rate was 60% with regular dilations required; for some patients this was long term. The energy delivered causes water vaporization, protein coagulation, and tissue necrosis. Others have also reported up to 55% of patients will require repeat ablations after the first 12 months to achieve ablation levels above 90%. The presence of intestinal metaplasia at the cardia is reported in 25% in a normal population. The relevance of these findings is to be defined in longer term studies where surveillance biopsies have included the cardia routinely. The lasers deliver light, at a specific wavelength, via optical fibers contained within a specifically designed balloon or bare cylinder. Technical considerations include the application of even light dosimetry with diffusing fibers/ perspex dilators and balloon devices, as well as ensuring the esophageal folds are flattened. Superficial mucosal necrosis occurs to a variable depth due to the increased resistance in coagulated tissue. At 16 years, 16 patients (50%) had sustained eradication, 11 (35%) partial, and 6% were lost to follow-up. The combined results in 129 patients were reported with short- (12 months), medium(42 to 75 months), and long-term (>84 months) outcomes. In the 30 patients undergoing surveillance, at follow-up time 25 months, 11 patients (37%) had recurrent neoplasia (P =. The mechanism of action causes an immediate effect, with failure of cellular metabolism due to intracellular and extracellular ice. The liquidized gas is applied until white frost appears, and then allowed to thaw after a period of at least 45 seconds. The dosing has varied from three cycles of 20 seconds to four cycles of 10 seconds and recently two cycles of 20 seconds. A 20-second application of liquid nitrogen will produce 6 to 7 L of gas at room temperatures. There has been concern with respect to perforation rates because of the gaseous distention,74 and this was reported in a single study. The majority of these deposits were within 5 mm of the neosquamo-columnar junction. It may be relevant to a group of highly selected patients and should be performed in specialist units. The numbers in the trial were small and the difference between methods of acid control was not significant. Recurrent metaplasia/ dysplasia should be treated according to the histology of the lesion. In this group of patients there were no patients with dysplasia or buried Barrett. Radiofrequency ablation vs endoscopic surveillance for patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia a randomized clinical trial. It has been stated that for ablation to be preferable to surveillance, there should be a decreased risk of the important endpoints such as cancer, or worse cancer death; the decrease in risk should be durable without the need for repeated treatments, and the treatment should be relatively easy to administer, without excessive cost or treatment risk. For patients with intermediate or low risk of malignant transformation, the decision between continued surveillance only or ablation with surveillance is complicated by the lack of comparative studies with the important endpoints of esophagectomy or cancer death. A prospective randomized trial of two different endoscopic resection techniques for early stage cancer of the esophagus. Meta-analysis of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for tumors of the gastrointestinal tract.

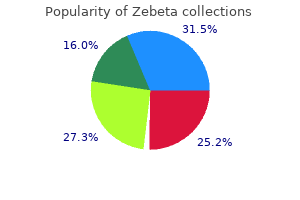

Purchase zebeta 10mg visa

Injury is highest when the refluxed gastric juice is a mixture of gastric acid and duodenal bile blood pressure medication options order generic zebeta online. This has led to the hypothesis that an improvement in the potency of acid suppression therapy will reduce the incidence of epithelial damage and progressive disease. Indeed, clinical experience with potent acid suppression therapy has shown a marked reduction in acid-related complications such as esophagitis and strictures. Acid alone in physiologic concentrations is not very damaging, but in high concentrations the incidence of epithelial damage is substantial. These findings reinforce the concept of an acid and bile synergism in the cause of mucosal injury. The development of the Bilitec probe to monitor bilirubin as a marker for duodenal juice greatly simplified the study of duodenogastroesophageal reflux. The height of the elevation depends on the baseline level of gastric pH, which varies depending on whether the patient is taking acid suppression therapy. As the pH approximates 7, more than 90% of bile acid becomes soluble and completely ionized. Acidification of bile to a pH below 2 results in an irreversible bile-acid precipitation. On the other hand, in a more alkaline gastric environment, which occurs with excessive duodenogastric reflux or acid suppression therapy, bile acids remain in solution and are only partially dissociated. When nondissociated, nonpolar bile-acid molecules reflux into the esophagus, they can enter the mucosal cells. Once in the cell, where the pH is 7, they become completely dissociated into polar ions and are trapped intracellularly in concentrations of up to 7 times the luminal concentrations. This requires that a gastric pH of 6 to 7 be maintained 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, while the patient is on acid suppression therapy. This is not only impractical but probably impossible without very high doses of medication. Several studies were initiated to determine whether bile acids, now solubilized in gastric juice owing to the widespread use of acid suppression therapy, were responsible. Patients with exposure to increased acid and bile had the highest prevalence of endoscopic and histologic epithelial injury. Between these extremes, bile acids can exist in their associated form and remain soluble. In this form, they can enter the cell with detrimental effects; hence the pH range between 2 and 6. The acquired etiology was confirmed experimentally in the landmark report of Bremner et al. When present, the intestinalized cardiac mucosa is always most proximal and the oxyntocardiac mucosa most distal, with cardiac mucosa interposed between them. He found that in the vast majority of children and adults under age 20, the squamous epithelium transitioned directly with the oxyntic epithelium of the gastric fundus. On the other hand, cardiac mucosa appeared in specimens from patients older than age 20, but its length was almost always less than 1 cm. Even in these older patients, there were a considerable number of individuals where the squamous epithelium transitioned directly to oxyntic mucosa in the fundus of the stomach without intervening cardiac mucosa. Based on these investigations, the traditional view that the anatomic gastric cardia is lined by cardiac mucosa may not be correct. It is hypothesized that because oxyntic mucosa of the fundus of the stomach is not affected by gastric juice, cardiac mucosa must come from exposure of the esophageal squamous mucosa to gastric juice. This process likely represents a change in the direction of differentiation of the germinal cells of the squamous epithelium toward metaplastic cardiac epithelium. Exposure of the effaced squamous epithelium to acidic gastric juice results in inflammatory damage and the formation of squamous epithelial islands separated by newly formed metaplastic cardiac epithelium. When the acid exposure is limited and in physiologic concentration, the newly formed metaplastic cardiac mucosa can undergo oxyntic transformation forming oxyntic-cardiac mucosa. This is a stable, glandular mucosa that is similar to the oxyntic mucosa of the stomach in that it contains both parietal and mucous cells and is more resistant to damage by refluxed gastric acid. In nearly all circumstances, metaplastic cardiac mucosa, when present, shows inflammatory and reactive changes referred to as carditis. The development of intestinal metaplasia within metaplastic cardiac mucosa is considered a detrimental change because this mucosa can progress to dysplasia and adenocarcinoma. Oxyntic transformation of metaplastic cardiac mucosa protects against the development of intestinal metaplasia and is a beneficial change. The length of the intestinalized cardiac mucosa could be as short as a few millimeters. The observation that some patients have cardiac mucosa without intestinalization suggests that intestinalization requires a specific condition or stimulus. Clinical studies have shown a time lag of 5 to 7 years after the onset of reflux symptoms for intestinalized cardiac mucosa to appear in adults. Cardiac-type mucosa with intestinal metaplasia within the vicinity of the high-pressure zone. This is due to the normal gradient between the positive pressure environment in the stomach and the negative pressure environment in the thoracic esophagus. Under these conditions, intestinalized metaplastic cardiac mucosa could appear within the lower half of the esophageal body without any apparent subsequent change in length over time. At any time during the process, specific luminal conditions or stimuli, such as exposure to a specific pH range in the presence of a specific solubilized bile acid, intestinalization of metaplastic cardiac mucosa can occur and set the stage for malignant degeneration. Studies have suggested that intestinalization of the metaplastic cardiac mucosa is initiated by exposure to a pH 3 to 5 resulting from the interaction of the reflux gastric juice, duodenal juice, and saliva at the squamocolumnar interface. Exposure to this pH range has been shown to encourage the phenotypic expression of intestinalization by metaplastic cardiac epithelial cells. Further, there was no association between the presence of intestinal metaplasia and H. The gap is filled with metaplastic cardiac mucosa, which can become intestinalized and give rise to visible Barrett esophagus in 2 to 5 years. The prevalence of intestinal metaplasia of the metaplastic cardiac mucosa is directly proportional to the length of the squamooxyntic gap. Consequently, clinical symptoms and endoscopy alone are not sufficient to confidently evaluate a patient with early disease. The best opportunity to reverse the process is when intestinal metaplasia of cardiac mucosa is microscopic and not visible on endoscopy. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a typical spectrum disease (a new conceptual framework is not needed). Selection of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease for antireflux surgery based on esophageal manometry. Outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with nonerosive reflux disease. Response of the distal esophageal sphincter to respiratory and positional maneuvers in humans. The interaction of the lower esophageal sphincter pressure and length of sphincter in the abdomen as determinants of gastroesophageal competence. Role of the overall length of the distal esophageal sphincter in the antireflux mechanism. Postprandial gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers and symptomatic patients. By 2030, one out of every 100 European men is projected to be diagnosed with esophageal adenocarcinoma before the age of 75 years. Proton pump inhibitor usage and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. Limited ability of the proton-pump inhibitor test to identify patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Review article: how valuable are proton-pump-inhibitors in establishing a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease

Syndromes

- Brain or spinal fluid injection (meningitis)

- As the air continues to be let out, the sounds will disappear. The point at which the sound disappears is recorded. This is the diastolic pressure.

- Impotence (in men)

- Twitching of facial muscles, arms, hands, legs, and feet

- Red spot on the skin, growing to become a sore (ulcer)

- Have you had any recent injuries or illnesses?

- Iron tests on the blood

- Infection

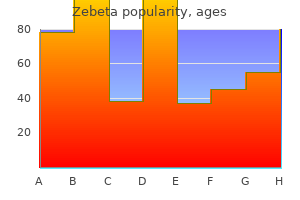

Cheap zebeta online american express

Is the Stretta procedure as effective as the best medical and surgical treatments for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease Update on novel endoscopic therapies to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review heart attack in sleep cheap zebeta express. Efficacy of transoral fundoplication vs omeprazole for treatment of regurgitation in a randomized controlled trial. Weight loss can lead to resolution of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a prospective intervention trial. An alginate-antacid formulation localizes to the acid pocket to reduce acid reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Baclofen decreases acid and non-acid post-prandial gastro-oesophageal reflux measured by combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH. Efficacy and safety of lesogaberan in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a randomised controlled trial. Imipramine for treatment of esophageal hypersensitivity and functional heartburn: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Editorial: low-dose tricyclics for esophageal hypersensitivity: is it all placebo effect Influence of citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, on oesophageal hypersensitivity: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of hypersensitive esophagus: 35. Antireflux surgery provides an anatomic and physiologic cure with durable symptomatic relief and prevention of the adverse consequences of ongoing esophageal exposure to caustic refluxate. Following the introduction of the laparoscopic approach in 1991 by Dallemagne and Geagea, the number of Nissen fundoplications performed annually increased threefold. While efficacy of medical therapy and concerns regarding potential complications of fundoplication have led to a recent decline in the number of operations performed annually in the United States, the pendulum may be swinging back with increasing concerns over the sequelae of chronic acid suppression. The principles of modern Nissen fundoplication are designed to most closely replicate the normal physiology of the gastroesophageal flap valve,10 including secure crural closure and the creation of a short, 360-degree "floppy" wrap around 2 to 3 cm of intraabdominal esophagus. The frequency and timing of reflux symptoms, the relationship to meals, symptom exacerbation in the supine or upright position, and difficulty swallowing should be noted. The response and the duration of medical therapy are also recorded, as this information has prognostic significance following fundoplication. In addition, patients may have atypical symptoms such as chronic cough, asthma, pulmonary disease, odynophagia, hoarseness, and chest pain. These patients should undergo cardiac evaluation, including a chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, and, if indicated, pulmonary function tests, in addition to the standard diagnostic evaluation for gastroesophageal reflux. Progressive dilation plus deterioration of the gastroesophageal flapvalve mechanism results in loss of the anatomic antireflux barrier and allows for acid and bile reflux. This well-established procedure has proved to be both durable and safe over a period of more than 25 years. Patients with typical reflux symptoms and erosive esophagitis (or Barrett esophagus and peptic stricture) do not routinely need a pH study to prove the diagnosis of reflux preoperatively. Air within the esophageal lumen causes an increase in impedance, whereas the presence of liquid refluxate within the esophageal lumen causes a decrease in impedance. By determining the temporal sequence of impedance events, one can establish the directional flow of gas and liquid within the esophagus. By coupling this technology with data from a standard pH probe, one can correlate both acid and nonacid refluxate with patient symptomatology. Standardization of reference ranges for normal patients and in patients with reflux, and improvement of the software used for data interpretation, have moved this technology from a research tool to clinical practice. Those with significant symptoms and concomitant reflux events (acid or nonacid) while taking acid-suppression therapy may be the ideal patients for surgical therapy. Preoperative endoscopic or medical treatment of esophageal stricture or peptic ulcer disease must be accomplished before surgery. In a patient with esophageal stricture, preoperative dilation to at least 16 mm (48 French) is advisable to minimize the chance that the customary postoperative dysphagia (a result of edema and early postoperative esophageal dysmotility) will be compounded by a tight stricture. If preoperative dilation to 16 mm is successful-several sessions are sometimes necessary-it is usually possible to extend the dilation intraoperatively to 18 or 20 mm, the standard-size dilators used by surgeons for calibrating the fundoplication. Severe strictures that are not responsive to dilation therapy should also be treated by esophageal resection. Fundoplication may be considered in such patients if subsequent pathology shows no progression to high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma. Despite the recent trend toward complete (Nissen) fundoplication in most patients, contrasting data suggest that long-term satisfactory results may be achieved with partial fundoplication. The intraoperative steps of surgical repair are relatively similar in both approaches. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, however, requires that the surgeon possess advanced laparoscopic skills. The approach to reoperative Nissen fundoplication should be individualized with the goal being long-term success of the procedure, since at the end of the day that is what will restore quality of life, independent of the approach. Most first-time redo procedures can be done laparoscopically, and several large series have demonstrated equivalent results with laparoscopic and open reoperation. It is important when planning a reoperation to consider why the prior procedure failed and address the cause of failure. An unrecognized short esophagus is one such potential cause, and a Collis gastroplasty may be an important addition during the reoperation in some patients. In the multiply reoperative foregut, consideration should be given to an alternative approach, such as an open thoracic or thoracoscopic approach or resection of the stomach or esophagus. The patient is placed in a split-leg position with both arms tucked and secured to the operating table. The first step involves safe entry into the abdomen, which is achieved in most patients by inserting a Veress needle at the umbilicus and establishing pneumoperitoneum. Creation of a short (2 cm), "floppy" (tension-free) fundoplication around the distal esophagus only and anchored to the esophagus either an open cut-down approach or alternative Veress location can be used. A camera port, to accommodate a 5-mm or 10-mm laparoscope, is placed just superior and to the left of the umbilicus, approximately 12 cm below the xiphoid and approximately 2 to 3 cm to the left of midline. The laparoscopic camera may be managed by the first assistant, a dedicated camera operator, or with a robotic camera holder. A thorough abdominal exploration with the laparoscope is routinely performed before initiating dissection. The third port, for liver retraction, is a 5-mm port placed on the right costal margin 12 to 15 cm from the xiphoid (depending on the size of the liver). The right crus and caudate lobe of the liver should be clearly visible through the gastrohepatic ligament or pars flaccida if the liver retraction is adequate. Small circles represent 5-mm radially dilating trocars and large circles denote 11- to 12-mm trocars. The caudate lobe of the liver is visible through the thin tissue of the pars flaccida. The liver retractor is stabilized with an endoscopic instrument holder attached to the operating table. The fourth port (5 mm), for the assistant, is generally placed midway between the liver retractor and the camera port. In the absence of a dedicated camera holder, the assistant can stand on the left side of the patient and control the laparoscope with the left hand. Exposure An atraumatic grasper is used by the assistant to provide retraction of the stomach. The operating surgeon uses an atraumatic grasper in the left hand and an ultrasonic scalpel or advanced energy device in the right hand. An aberrant left hepatic artery may be present in the pars flaccida in up to 13% of patients and often requires division as the dissection of the gastrohepatic ligament is carried superiorly toward the base of the right crus of the diaphragm. The posterior vagus nerve is identified and preserved as the posterior mediastinal tissue is bluntly swept medially. Using the open jaws of the atraumatic grasper to provide anterolateral retraction on the right crus of the diaphragm, the dissection is continued clockwise up to the phrenoesophageal membrane. The anterior vagus nerve runs along the esophagus in this region and should be identified and preserved. The dissection is then carried down the border of the left crus until the angle of His and the gastric fundus limit further inferior dissection. The open jaws of the grasper are then used to retract the right crus laterally, while the instrument in the right hand gently sweeps the esophagus medially.

Generic zebeta 5mg otc

These include pulmonary hypoplasia from restricted lung growth and decreased alveolar development 1 purchase zebeta 2.5 mg. Pulmonary hypoplasia is not strictly related to the herniated viscera, as muscularization around peripheral arterioles is also thought to contribute to the severe pulmonary hypertension. In general, posterolateral left-sided hernias are more likely to be symptomatic and identified in the neonatal period, whereas anterior defects may go undetected. Typically, a 2- to 4-cm posterolateral diaphragmatic defect is present, through which the abdominal contents herniate into the thoracic cavity. Most commonly, small bowel, spleen, stomach, liver, and/or colon may be in the chest. Patients with right-sided Bochdalek (non-Morgagni) type tend to have severely poor prognosis due to severe pulmonary hypotension/pulmonary hypoplasia. The large right lobe of the liver can occupy most of the hemithorax, and associated anomalous hepatic venous drainage is common. A rare form of anterior diaphragmatic hernia is included in the pentalogy of Cantrell. They most commonly involve the cardiac outflow tract, including ventricular septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot, transposition, and coarctation. They are typically located anteromedially on either side at the junction of the septum transversum and the anterior thoracic wall. They are most often asymptomatic, as the amount of pulmonary compression is minimal compared to posterolateral defects. In addition, patients typically have transverse colon herniation into the anterior mediastinum covered by a peritoneal sac. Most are discovered incidentally as an anterior chest mass or suspected pneumonia in an older child. It may also demonstrate associated polyhydramnios, which occurs in 75% due to gastrointestinal obstruction. The diagnosis may not be detected with prenatal ultrasound, as intermittent herniation of viscera into the thoracic cavity may occur. Fetal karyotyping should be offered with either chorionic villi sampling or amniocentesis, whichever is appropriate for gestational age at diagnosis. The parents should be encouraged to deliver in an appropriate tertiary care center with capabilities of advance respiratory care strategies and urgent pediatric surgical availability. An additional benefit is reduced intraobserver variability of fetal lung volume measurements commonly seen with ultrasound techniques. It has proven superior to "liver-up" versus "liver-down," as it allows the exact quantification of the amount of liver herniated into the chest. The most severely affected infants have respiratory distress immediately after birth, with associated hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and respiratory acidosis. Shunting of oxygenated blood may occur (persistent fetal circulation), which increases in proportion to the pulmonary hypertension. This is estimated by comparing preductal (right arm) and postductal (left arm or lower extremities) oxygen saturations, which will demonstrate decreased postductal readings. Presence of liver in the chest ("liver-up") has not been consistently shown to predict mortality, although most studies suggest a decreased survival. Although the chest is opacified early (A), continued introduction of air results in eventual bowel distention (B). Mediastinal compression may shift the trachea to the contralateral side or produce tension physiology with obstructed venous return. Pallor, cyanosis, sternal retractions, and grunting all signify increased work of breathing and impending deterioration. A chest radiograph should be done soon after birth, which typically demonstrates loops of bowel located in the chest. The nasogastric tube location is useful for identifying the stomach position within the chest or abdomen. In addition to the chest x-ray, additional imaging studies include a transthoracic echocardiogram and head ultrasound. The echocardiogram is performed to rule out associated anomalies and assess ventricular function/ pulmonary hypotension. This is best performed on day of life 2 to not overestimate the degree of pulmonary hypertension. It was later understood that the majority of patients showed a deterioration in respiratory mechanics after a brief postoperative "honeymoon period" of adequate gas exchange. Reduction of hernia contents into the abdomen rarely results in reexpansion of the lungs, as they are hypoplastic rather than atelectatic. A nasogastric tube should be inserted to allow gastric and intestinal decompression. Typically, umbilical venous and arterial catheters are placed along with oxygen saturation probes in the pre- and postductal locations to allow for shunt estimation. Excessive stimuli can easily exacerbate pulmonary pressures and lead to increased shunt flow/ desaturations. For this reason, infants are kept sedated in beds/incubators with radiant warmers and external stimulation is limited. Muscle paralysis should only be used in extreme circumstances due to ventilatory consequences and added morbidity. With advances in postnatal resuscitation and care, the survival rate has improved significantly. One of the most beneficial changes seems to be the idea of less aggressive ventilatory strategies. In 1985, Wung and colleagues proposed permissive hypercapnia as a way to limit barotrauma and still achieve sufficient tissue oxygenation. If customary measures cannot achieve adequate oxygenation and ventilation, then nonconventional ventilatory modes may be used. In theory, vasodilator therapy should lead to improvement, but it has shown to be unsuccessful due to inadequate pulmonary vasodilation and increased shunting from systemic hypotension. Hemorrhagic complications may be seen in up to 60% and include bleeding at the cannulation site, surgical site, head, chest, and gastrointestinal tract. For the stable infant without pulmonary hypertension, repair can be safely done after a 48-hour period of stabilization and adjustment to postnatal life. Surgical repair should be ideally delayed until the patient is hemodynamically stable for at least 24 hours. Once the abdomen is entered, the bowel is reduced from the chest with gentle downward traction. Great care should be exercised during mobilization, as the spleen and liver may develop subcapsular hematomas and life-threatening hemorrhage with traumatic reduction. If a hernia sac is present, it should be excised to minimize the risk of recurrence. Although the anterior rim of diaphragm is usually prominent, the posterior rim is typically diminished and obscured in the retroperitoneal tissue. The posterior diaphragmatic tissue must then be mobilized from the retroperitoneum, revealing the size of the diaphragmatic defect. The most commonly used mesh is Gore-Tex, although more recent biologic and absorbable mesh have also been used with no difference in recurrence or postoperative complications. Overall, use of prosthetic mesh is associated with a higher risk of recurrence, especially with a large initial defect or complete diaphragmatic agenesis. A Silastic sheet can be used between fascial edges as a temporizing measure, with slow closure over the ensuing days-weeks. Eventual abdominal closure leads to a ventral hernia that can be dealt with outside the neonatal period. Additional techniques for repair of defects include internal oblique rotation flap or split abdominal wall muscle flap. Due to the associated pulmonary hypoplasia, there is usually adequate room after the bowel is reduced into the abdomen. Typically, three ports are used and include a 5-mm port in the site of the Veress insertion (4-mm camera), 3-mm port in the left anterolateral chest wall (bowel grasper), and 5/3-mm convertible port in the right posterolateral chest wall (bowel grasper, needle driver). The posterolateral edge of the diaphragm is unfurled from the retroperitoneal tissue revealing the extent of the hernia, and needles can be introduced through the 3- to 5-mm port or through the chest wall. Sutures are placed approximately 1 cm apart, and knots may be tied either intra- or extracorporeally.

Generic 2.5mg zebeta overnight delivery

Carcinomas arising in duplication cysts are rare and include carcinoid tumors blood pressure chart for 80 year old woman purchase zebeta online now, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma. The indications for surgery for intestinal duplications are the same as those of the stomach and duodenum: bleeding, obstruction, perforation, intractability, or suspicion of malignancy. Pneumatosis is identified radiographically and grossly when small mucosal, submucosal, or subserosal air-filled cysts develop in benign and life-threatening conditions. When associated with hepatoportal venous gas, it can indicate the need for emergent surgical exploration. There exist two types of gastric pneumatosis, emphysematous gastritis and gastric emphysema. Emphysematous gastritis may occur by direct inoculation of gas-producing bacteria into the gastric mucosa or by hematogenous spread. Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, streptococci, staphylococci, and Enterobacter species are the most frequent pathogens. Immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, ingestion of corrosive substances, alcoholism, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug ingestion are common predisposing factors. Gastric emphysema is noninfectious in origin and occurs primarily due to entry of intraluminal air into the wall of the stomach from traumatic, obstructive, and pulmonary origins. Traumatic gastric emphysema caused by transmural diffusion of air after a mucosal injury, can occur after esophagogastroduodenoscopy, severe vomiting, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Obstructive gastric emphysema has been reported in patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to gastric cancer, gastric volvulus, duodenal obstruction, and hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pulmonary gastric emphysema is theoretically caused by alveolar rupture and air tracking through the mediastinum to the gastric wall. Patients may present with nausea, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, or abdominal pain, and if the diagnosis is correct they will follow a benign course that resolves spontaneously without sequelae. Different mechanisms are associated with different mechanical, bacterial, or biochemical pathologic conditions. Pneumatosis intestinalis, which typically presents in adults in the fifth to eighth decade, is idiopathic in 15% of patients and secondary in 85%. Pneumatosis can be reproduced experimentally by insufflating air into a segment of bowel in which mucosal incisions have been made. Alternatively, gas-forming organisms that invade the submusosa can produce pneumatosis. The clinical quandary is to differentiate benign pneumatosis from acute surgical problems: intestinal ischemia, infarction, obstruction, and perforation. In patients who have a history, physical exam, and laboratory findings of an acute abdomen, exploration of the abdomen is indicated. The location of pneumatosis and the presence of free peritoneal air may not indicate severity of disease. Other diseases and conditions associated with pneumatosis include infection, pulmonary disease, mechanical ventilation, asthma, cystic fibrosis, immune compromise, inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcer disease, cancer, diabetes, scleroderma, Hirschsprung disease, intestinal pseudoobstruction, amyloidosis, and collagen vascular disease. Most patients with idiopathic pneumatosis do not come to the attention of the clinician. However, in patients who present to the emergency department with pneumatosis, bowel ischemia is the most likely diagnosis. The critical decision in patient management is whether to treat the patient conservatively or proceed with emergent exploratory laparotomy. In patients whose clinical findings are inconsistent with an acute abdominal catastrophe, conservative management and a search for other causes should be undertaken. A general knowledge of the potential diagnoses and management implications of these disorders is essential to the armamentarium of the general surgeon. Given the uncommon nature of many of these lesions, experience and the art of medicine are often required for successful management. Appropriate caution for malignant potential should be observed, although overtreatment of incidental conditions should be avoided. Histopathological study using computer database of 10 000 consecutive gastric specimens: (1) benign conditions. Submucosal tumors: comprehensive guide for the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Clinical applicability of various treatment approaches for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Gastroduodenal intussusception secondary to a gastric lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. Duodenoduodenal intussusception: report of three challenging cases with literature review. Gastric foregut cystic developmental malformation: case series and literature review. Isolated duodenal duplication cyst presenting as a complex solid and cystic mass in the upper abdomen. Vomiting-induced gastric emphysema and hepatoportal venous gas: a case report and review of the literature. Natural history, clinical pattern, and surgical considerations of pneumatosis intestinalis. Warner The spectrum of diseases of the stomach and duodenum in the pediatric population is broad. This article discusses the evaluation and management of some of the more common surgical disease in infants and children within the first two decades of life. Malrotation is the anatomic anomaly that predisposes infants to volvulus because of a narrow mesenteric pedicle that can lead to intestinal infarction. The bowel appears uniformly echogenic until the third trimester, when more prominent meconium-filled large bowel may become apparent. These obstructions are commonly associated with polyhydramnios as the fetus is incapable of swallowing and absorbing sufficient amniotic fluid. The rate of associated anomalies will vary depending on the underlying developmental abnormality. However, antenatal diagnosis of foregut pathology should generally prompt further evaluation of associated anomalies. For instance, approximately half of patients with duodenal atresia will have associated anomalies including trisomy 21, malrotation, skeletal and other gastrointestinal abnormalities. Over the next few weeks, the posterior wall of the foregut grows faster than the anterior wall to form the greater and lesser curves of the stomach. The lumen of the duodenum is obliterated at the fifth week of gestation by the proliferation of growing epithelial cells. Recanalization through vacuolization occurs around the eighth week with patency typically restored by 11 weeks. Errors in this recanalization process may result in proximal small bowel obstruction. During the 5th to 11th week of gestation, the duodenum shifts from a midline, freely mobile structure to the normal position in the upper retroperitoneum. The pancreas is formed by dorsal and ventral pancreatic buds that originate from the endodermal lining of the duodenum just distal to the forming stomach. As the pancreas increases in size and the stomach completes its rotation, the duodenum shifts toward the left and results in the characteristic C-shaped loop. Infants presenting with bilious emesis should have a high index of suspicion for malrotation and possible volvulus. Gastric and duodenal duplications represent ~15% in a series spanning 31 years by Iyer and Mahour, with the remainder of enteric duplications occurring in the distal small bowel, colon, and rectum. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including persistent fetal enteric diverticula, incomplete recanalization following obliteration of the lumen during duodenal development, and the "split notocord" theory, whereby abnormal adhesions persist between the ectoderm and endoderm leading to herniation of the yolk sac between the vertebra, resulting in local duplication of the gut. Surgical treatment of the pediatric patient requires a thorough understanding and knowledge of developmental biology, in addition to the unique physiologic and pathologic processes. Many congenital anomalies of the stomach and duodenum are identified prenatally or in the neonatal period, while other lesions are acquired and may manifest later in childhood and adolescence. They primarily occur on the mesenteric side of the involved segment and have variable communication with the lumen of adjacent bowel. Two-thirds of patients are diagnosed within the first year of life, while many asymptomatic patients or patients with mild symptoms may remain undiagnosed until adulthood. Many of the symptoms are a result of a mass effect as the duplication grows in size from accumulating mucosal secretions. Patients may present relatively asymptomatic with a mobile mass or increasing abdominal girth.

Purchase genuine zebeta line

We have favored placing the port just below the costal margin in the epigastric region prehypertension diabetes cheap 5mg zebeta with mastercard. The tubing is brought out from the abdomen through a stab wound on the medial side of this incision, as far to the end of the incision as possible. This allows the tubing to emerge through the fascia and take a natural slow bend medially to be joined to the port. Securing the tubing to the port and then the port to the fascia in the incision site completes the operation except to visually confirm that addition of saline to the system causes the band to expand and not leak. However, complications can occur, and these have been well described in the literature. Any such symptoms of new onset need to be investigated promptly for either simple excessive restriction or, more commonly, prolapse of the band. Prolapse occurs when the stomach below the band herniates up into the central lumen of the band and too much stomach is forced into this space. In severe cases the prolapse can lead to ischemia and gangrene of the prolapsed portion of the stomach. Chronic prolapse is seen at times with surprisingly large protrusions of the distal stomach up and over the edge of the gastric band. Prolapse can occur at any time after the procedure, and its incidence slowly rises with duration of the band being in place. If doubt exists, a low-volume Gastrografin or barium swallow will confirm the diagnosis. This will, in most cases of acute prolapse, provide enough reduction in the restriction of the prolapsed stomach to allow it to slip back down through the band and resume its normal position. However, if removal of all fluid does not produce immediate relief of symptoms by the patient, a swallow study is indicated. If the swallow shows a large and persistent prolapse, emergent surgical therapy is indicated to laparoscopically reduce the prolapse and prevent gastric ischemia. A laparoscopic approach to freeing the buckle of the band, unbuckling the system, reducing the prolapse to its appropriate location, and repositioning and rebuckling the band is quite feasible. Chronic stenosis or band placement too high onto the distal esophagus may produce esophageal obstruction and dilation. Resolution of the obstruction will usually result in the esophagus regaining its normal size. Failure to secure the port to the fascia can result in the port turning in the subcutaneous space and being unable to be accessed for further adjustments. When such adjustments are made, a good rule of thumb is to have the patient drink several swallows of water quickly after the adjustment is made. If the patient feels the water stop and give a sensation of partial blockage, then the adjustment is too tight and must be loosened. Optimal restriction varies from patient to patient, but in general a goal of restriction to one cup of food or less at a meal and production of satiety for at least a few hours after eating are the goals of an optimal adjustment. It achieved initial popularity in the mid 1970s and has remained a standard operation since that time. The technique of creating the gastrojejunostomy and the length and location of the Roux limb has varied from surgeon to surgeon. No optimal technique or configuration has emerged, although some differences have been shown. Its performance using a laparoscopic approach has clearly been an improvement over the open approach, as with all other operations where minimal access has been used. Elimination of incisional hernias, decreased pain and recovery time, and decreased overall complication rates and mortality have all been confirmed with using the laparoscopic approach. Failure of a trial of dieting and mental stability are also considered standard criteria. Other criteria vary among surgeons and institutions, including upper and lower age limits, size limits, and requirements of cessation of addictive habits. The mesentery is then further divided with the Harmonic scalpel to obtain as deep a division of the mesentery as possible without encountering the very large vessels at the base of the mesentery. The proximal end of the Roux limb is then marked by suturing a small Penrose drain to it. Then the mesenteric defect at the enteroenterostomy is closed with a running permanent suture. The transverse colon mesentery is now grasped and elevated, exposing the lower portion of the mesentery near the ligament of Treitz. A defect is made in the mesentery to the left and a few centimeters above the ligament of Treitz. This location usually avoids major vessels, but the surgeon must be aware of the vascular anatomy, if visible, and cautious not to disrupt it unnecessarily. Openings between mesenteric vessels are easier to find than dealing with bleeding from major mesenteric vessels. Once the mesentery has been opened to expose the lesser sac, the posterior surface of the stomach can be seen. It is grasped and pulled out of the mesenteric defect a few centimeters, after which the plane below the stomach is confirmed with a grasper. Usually if one can pass 4 cm of bowel or more past the cut edge of the mesentery, that will suffice for later retrieval. It is very easy to have the bowel twisted a full 180 degrees or more between first passing it to the left upper quadrant then retrieving it to pass it through the transverse colon mesentery. The mesentery of the Roux limb must be visually confirmed without a doubt as being straight and vertical as the limb is passed superiorly through the transverse colon mesentery. The Harmonic scalpel is used to create an opening in the mesentery along the lesser curvature of the stomach. However, for very large patients, creating this opening at the incisura is advisable because the longer gastric pouch is often needed to allow the Roux limb to easily reach the proximal stomach without tension. Then I prefer to size the pouch with an Ewald tube (30 French) and place the stapler close to but not directly adjacent to the tube, which is visible by the contour it creates on the gastric surface. It is important to exclude the fundus from the proximal part of the newly created gastric pouch. Similarly, the anesthesiologist needs to double confirm there are no temperature probes or orogastric tubes in the stomach other than the Ewald tube. If it is not, the inferior surface of the transverse colon mesentery must again be exposed and the Roux limb passed into the retrogastric space again. I continue to use a retrogastric retrocolic location of the Roux limb due to the fact this is the shortest distance from between jejunum and proximal stomach. A more popular approach is to bring the Roux limb directly anterior to both transverse colon and distal stomach and create the gastrojejunostomy. This approach is technically easier, except when the mesentery of the Roux limb is short and there is difficulty in stretching the Roux limb to reach the proximal gastric pouch. For the retrocolic retrogastric approach, I now place the proximal suture line of the Roux limb directly adjacent to the distal part of the proximal gastric pouch. The distal 5 cm of gastric pouch is then tacked to the side of the proximal 5 cm of the Roux limb with a running absorbable suture. We have found that the linear stapler is associated with an insignificant incidence of postoperative stenosis, whereas the circular stapler in our experience yielded a 10% or higher stenosis rate. The Ewald tube serves as a good backstop against which to make a gastrotomy in the end of the pouch. We have not found that restricting the anastomotic size has any relationship to long-term postoperative weight loss. The staple defect is closed with a running layer of absorbable suture and reinforced with a second such layer. An intraoperative leak test is now performed by having the anesthesiologist forcefully inject a methylene blue dye solution into the lumen of the proximal pouch, after having readvanced the tip of the Ewald tube to that level. For this procedure, the Roux limb must be secured to the jejunum at the ligament of Treitz to prevent the Roux limb from telescoping up into the retrogastric space and becoming kinked and obstructed. Further sutures between the two limbs are placed, as well as sutures to close the space between the left lateral side of the Roux limb and the transverse colon mesentery. Port sites 12 mm or larger are closed with laparoscopically passed sutures for the fascia. Postoperative care includes providing adequate analgesia, early ambulation, liquids on postoperative day 1, and discharge on postoperative day 2 on our phase 2 gastric bypass diet (blenderized food). I still perform a Gastrografin swallow on the first postoperative day to confirm no distal obstruction, as well as no obvious leak. There was a significant improvement in obesity-related comorbid medical problems for all problems assessed after 10 years.

Petroselinum crispum (Parsley). Zebeta.

- Kidney stones, urinary tract infections (UTIs), cracked or chapped skin, bruises, tumors, insect bites, digestive problems, menstrual problems, liver disorders, asthma, cough, fluid retention and swelling (edema), and other conditions.

- Are there safety concerns?

- Are there any interactions with medications?

- Dosing considerations for Parsley.

- What is Parsley?

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96771

Purchase zebeta 10mg with amex

After the sac has been reduced from the mediastinum blood pressure chart neonates purchase zebeta canada, and the areolar dissection complete, the stomach generally has completely returned tension free, to its normal subdiaphragmatic location. At all times during the procedure, care is taken to avoid injury to the peritoneal lining covering the crura so to preserve the integrity and allow for successful primary closure. We have found that, if after complete mobilization of the hernia and sac, if crural tension is still present, inducing or augmenting an existing left-sided pneumothorax (as described earlier) may yield a more prominent "floppy diaphragm sign," allowing for a tension-free primary repair. Clear communication with the anesthesiologist is important when inducing or augmenting the pneumothorax to allow him or her to monitor and correct any hemodynamic instability. If crural integrity has been compromised or there is still tension preventing primary repair, one should consider the addition of a right- or left-sided crural-relaxing incision and mesh reinforcement. There has been debate regarding primary closure versus the routine use of mesh to reinforce the hiatal repair. Two prospective randomized trials have compared primary closure with mesh-reinforced repair, with short-term outcomes initially favoring a reduction in recurrent herniation in the mesh-reinforced group. In a subsequent analysis at a median follow-up of 58 months, 59% of patients who received a primary hiatal repair and 54% who received a mesh-buttressed repair were noted to have a recurrence. Longer-term outcomes may well see a further increase in symptoms requiring reoperation, and clearly the outcomes of this trial showed no benefit to the routine use of mesh reinforcement for the crural repair. In our center, we have found that in the vast majority of patients, we can achieve primary crural repair if the principles of complete esophageal and sac mobilization and preservation of crural integrity are followed. The crura are approximated with two or three interrupted nonabsorbable sutures placed posteriorly with the esophagus lying in a neutral, tension-free position within the hiatus. If any tension is present, we make sure the crura are mobilized by using a number of routine steps. For example, freeing up the spleen from the edge of the left crus can relieve some of the tension in this location. Normally, the spleen lives in the left upper quadrant and is not adherent to the left crus. However, after years of gastric migration into the chest, the short gastrics and residual posterior hernia sac can "drag" the spleen toward the crus and actually leads to scarification at the left crural edge. This can generally be easily mobilized with little risk to the spleen if care is taken. Next, if tension remains, we consider adding a controlled tension pneumothorax (as previously described) to the left side. This creates a very favorable "floppy diaphragm" and, in almost all cases, allows a tension-free approximation of the crus both posteriorly and anteriorly. It is not uncommon to have to reintroduce carbon dioxide into the left hemithorax every few minutes to maintain this floppiness, thus we often place a 5-mm port above the left costal margin. Alternatively, simply opening the left pleura in the mediastinum accomplishes this purpose. Care is taken to avoid an artificial angulation or "speed-bump" deformity of the esophagus as it passes through the hiatus from excessive posterior crural closure. However, because many of these patients are kyphotic, and posterior crural closure actually adds intraabdominal length to the esophagus, some surgeons will add additional posterior sutures. If this is not achieved, the esophagus and stomach continue to exert axial forces on the crural closure and a recurrence is more likely to result. Constant visualization of the anterior and posterior vagus nerves is important to avoid injury to these structures. In the event that 2 cm of tension-free intraabdominal esophagus cannot be established, a Collis gastroplasty should be performed if the plan is to proceed with a fundoplication. We have found over the years, that with more experience and better esophageal mobilization, the need for a Collis gastroplasty has been reduced and when it is needed, the length of the Collis gastroplasty can be kept to a smaller distance. This is very much an experience and judgment decision: you want the space to be minimal because, if too patulous, you risk herniation of the wrap and/or other abdominal contents, and too tight can produce dysphagia. We have noted that certain patients, particularly elderly, frail patients with an upside-down stomach and essentially 100% intrathoracic location, have primarily obstructive symptoms and minimal heartburn. In this group, we are evaluating repair without a fundoplication and are putting these data together in an attempt to better clarify who might be predicted to do well without a wrap. Some surgeons have described gastropexy as a single point of fixation using suture or the placement of a gastrostomy tube. We begin the gastropexy near the angle of His to the left crus and then follow the cardia and fundus along the diaphragm, just above the spleen, essentially in a line very near to where the short gastrics used to live. Gastropexy sutures are placed on a diaphragmatic fold just a few millimeters above the spleen, approximately 2 cm apart over a distance of 10 to 14 cm. By more or less duplicating what used to be the line of the short gastrics, we are attempting to recreate normal anatomy of the intraabdominal stomach, not just a "pexy. At the completion of the operation a nasogastric tube can be placed by the anesthesiologist or surgeon under direct laparoscopic visualization. Early trials with permanent synthetic mesh suggested a reduction in hernia recurrence rates, but for most esophageal surgeons the potential complications associated with synthetic mesh, including erosion and difficult reoperations, outweigh the potential benefit. Two randomized trials using biologic absorbable mesh have failed to show a benefit for the use of this type of mesh. However, it is important to recognize that neither trial aggressively assessed or treated tension. The fundamentals of hernia surgery dictate that tension is the enemy of any hernia repair, and it is logical that this tenet holds true at the hiatus as well. Consequently, future studies need to focus on adequately addressing tension in the form of relaxing incisions for crural tension or adding an intentional pneumothorax to create a "floppy diaphragm" to relieve tension during crural repair. In addition, the role of Collis gastroplasty for axial esophageal tension should be further evaluated in controlled trials, and further evaluation of the role of nonpermanent and permanent mesh reinforcement of the crural closure. In addition, given the results of a number of reports of high recurrence rates, the onus is on the surgical team to document their surgical results immediately postoperatively and then to follow this group of patients and establish your own recurrence rates. Patients are discharged on liquid narcotic pain medication for 1 to 3 days and early are converted to oral liquid Tylenol. Patients are advised to refrain from heavy lifting long term and limit lifting to 15 to 20 pounds. In addition, we educate the patient on the avoidance of constipation and to watch for and treat early symptoms of gas bloat, using dietary manipulation and simethicone as needed. Patients follow up in clinic in 2 weeks with a chest x-ray and then annually with a barium esophagram to monitor for radiographic recurrence. This close attention to detail facilitates early recognition of relevant symptoms, including dysphagia, and appropriate interventions to assist with patient comfort and satisfaction with quality of life. Routine dietary changes should include avoiding gassy foods and slowing down the eating process to avoid excess gas swallowing, following what we call the "25 chew" rule. We also recommend four to five small meals per day and avoiding large feast-type meals. In the early postoperative period, major postoperative complications include pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary embolisms can occur in a small subset of patients. Postoperative mortality in the setting of elective repair should be less than 1% but is higher in patients older than 80 years and in patients requiring urgent repair. Importantly, 90% of patients reported good to excellent scores on evaluation of their symptomatic outcomes, with only 3. However, we are not accepting these "small recurrences" as ideal, and we are continuing to evaluate our surgical results and hope to achieve "Pearson-like outcomes" of a less than 2% reoperation rate at long-term follow-up. In this setting, we have shown that the outcomes, both short and long term, and the reoperation rates with a minimally invasive approach can be comparable with the best open series. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Primary laparoscopic and open repair of paraesophageal hernias: a comparison of short-term outcomes. Laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernia results in long-term patient satisfaction and a durable repair. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia: long-term results with 1,030 patients. A clinical prediction rule for perioperative mortality and major morbidity after laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. Laparoscopic clam shell partial fundoplication achieves effective reflux control with reduced postoperative dysphagia and gas bloating.

Buy zebeta 10 mg on-line

Immediately after the esophagus is distended by gas prehypertension 39 weeks pregnant buy zebeta cheap, the patient drinks high-density barium as quickly as possible in the upright position. Uniform distribution of this thick barium on the luminal surfaces of the gasdistended esophagus allows demonstration of the entire mucosa of the esophagus. Therefore this chapter begins by describing the essential techniques, normal findings, and common artifacts of the esophagram. Subsequently, the utility of the esophagram is discussed in the settings of gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal motility disorders, postoperative esophagus, and esophageal neoplasms (a discussion of the role of cross-sectional imaging, especially positron emission tomography, for esophageal tumor staging is included in this section). Finally, miscellaneous conditions such as hiatal hernias, esophageal rings and webs, less common types of esophageal strictures, caustic injury, and esophageal perforation, diverticula, and varices are discussed and illustrated. The mucosa is featureless, except for the occasional tiny filling defect caused by undissolved effervescent crystals (arrows). These artifactual filling defects usually change position on sequential upright images. Because the esophagus remains distended by gas for only a short time in the upright position, the radiologist needs to obtain air-contrast images quickly. As the esophageal lumen collapses, residual barium is trapped between redundant longitudinal mucosal folds of the esophagus, resulting in a mucosal relief image of the esophagus. Mild thickening and irregularity of the distal longitudinal folds may be a subtle sign of reflux esophagitis. Before tilting the table into the horizontal position, the radiologist should determine the need for upright evaluation of swallowing and the cervical esophagus. Anatomically, the two main sites of abnormalities resulting in dysphagia are the oropharynx and the esophagus. When patients report food sticking, and point to the neck or thoracic inlet as the level of obstruction, their symptoms may result from oropharyngeal dysphagia or esophageal dysphagia. However, when patients report food sticking, and point to the substernal region as the level of obstruction, their symptoms typically result from an esophageal dysphagia. Therefore, referring physicians and surgeons, as well as radiologists, should ask the patient two questions: (1) Does food stick When the patient indicates that food sticks at the level of the neck or thoracic inlet, the oropharynx and cervical esophagus should be evaluated in the upright position. For example, the radiologist puts the patient in the upright lateral position and observes a swallow fluoroscopically. Structural causes of oropharyngeal dysphagia such as cricopharyngeal bar, cervical esophageal stricture, or cervical esophageal web are readily identified in the lateral position. When a neuromuscular cause of dysphagia is suggested by this single upright view, it is best evaluated by a speech pathologist trained in the evaluation of dysphagia. The speech pathologist interviews and examines the patient before performing a video swallow study with multiple consistencies of barium. In fact, we often perform the video swallow, in consultation with speech pathologist, and the esophagram during a single patient visit to the fluoroscopy suite. This patient convenience is facilitated by our referring physicians and surgeons, who are aware of the variable etiology of so-called high dysphagia (when the patient indicates that food sticks at the level of neck or thoracic inlet). Consequently, they can order both the video swallow study and the esophagram initially, or they can give us permission to evaluate the esophagus as necessary based on the result of the video swallow. A motion-recording device that captures 30 frames per second is very helpful for the evaluation of swallowing. This type of continuous recording captures the dynamic events of swallowing far better than rapid sequential radiographic images captured at 4 to 8 frames per second. The single-contrast phase of esophagram is performed in the prone, right anterior, oblique position with respect to the horizontal fluoroscopy table. Patients drink as rapidly as possible in this position to produce maximal esophageal distention. Fixed segments of subtle esophageal narrowing become apparent only during maximal esophageal distention. If the patient cannot drink barium rapidly enough to sufficiently distend the lumen, areas of segmental narrowing are likely to go undetected. Esophageal motility should be tested by single swallows of barium with patient in the prone, right anterior, oblique position. To prevent esophageal peristaltic inhibition, patients are asked not to swallow between swallows. The primary peristaltic wave initiated by swallowing should propagate through the entire esophagus and result in bolus passage into the stomach. The trailing edge of the peristaltic wave resembles an inverted V, as sequential muscular contractions obliterate the esophageal lumen from proximal to distal. Frequently, a small amount of barium remains in the middle third of the esophagus after passage of the primary peristaltic wave. This small residual volume of barium should not be interpreted as abnormal motility since this esophageal segment is normally the zone of lowest normal contractile amplitude. In normal patients, 95% of swallows are accompanied by normal esophageal peristalsis. Therefore, abnormal peristaltic function, especially nonpropulsive (tertiary) contractions, should be interpreted with caution in older individuals. As the esophagram comes to an end, we return the fluoroscopy table and the patient to the upright position. When patients complain of difficulty swallowing pills, or we are suspicious of an esophageal stricture based on prone, single-contrast images, we ask them if they are willing to swallow a 12. None of these items should be administered by the radiologist to a patient at risk of aspiration. In addition, patients have the right to refuse to swallow a tablet or other food bolus. Many patients, especially those with oropharyngeal causes of dysphagia, are frightened of choking on the pill or food bolus. A smooth posterior impression at the pharyngoesophageal junction (arrow) caused by failure of cricopharyngeus muscle to relax. The caliber of the normal esophagus increases slightly just superior to the level of the gastroesophageal junction (arrows). This evaluation is especially relevant in patients who report food sticking in region of neck or thoracic inlet. The likelihood of an oropharyngeal cause of dysphagia in these patients is more likely than it is in those patients who report food sticking in the substernal region. This upright lateral view may suggest neuromuscular causes of dysphagia, best evaluated by speech pathologists. The abnormality revealed most commonly by these lateral images is a cricopharyngeal bar at the pharyngoesophageal junction. A brief examination of the stomach contributes to the evaluation of patients complaining of dysphagia. Neoplasms of the gastric cardia can present with dysphagia, and may be overlooked if the stomach is not evaluated. The normal esophageal ampulla (vestibule) is sometimes confused with a hiatal hernia. Unlike a hiatal hernia, the ampulla does not contain gastric folds and will demonstrate typical esophageal peristalsis. Closely spaced, transient, transverse mucosal folds, presumed secondary to longitudinal muscle contractions, typically occur immediately after an episode of gastroesophageal reflux. Contributory factors include the volume and composition of the gastric refluxate, altered esophageal mucosal resistance, and the effectiveness of esophageal clearance. Although other tests are more accurate in quantifying these etiologic factors, the esophagram may provide clues that point to the need for further evaluation. Radiographic signs of abnormal esophageal motility suggest poor esophageal clearance of any refluxed material that can be evaluated with esophageal manometry. Furthermore, dysphagia and chest pain, more typical symptoms of motility disorders, may be absent in these patients. Symptoms of heartburn are even more common in achalasia, occurring in 40% of patients. In patients with classic achalasia, the esophagram is usually characteristic, confirming the diagnosis.

Order 5mg zebeta mastercard

Surgical therapy of esophageal carcinoma: the influence of surgical approach and esophageal resection on cardiopulmonary function blood pressure too low symptoms zebeta 2.5 mg overnight delivery. Three-field lymph node dissection for squamous cell and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Prevalence and location of nodal metastases in distal esophageal adenocarcinoma confined to the 29. Technical factors that affect anastomotic integrity following esophagectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophagectomy for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intrathoracic manifestations of cervical anastomotic leaks after transthoracic esophagectomy for carcinoma. Intrathoracic manifestations of cervical anastomotic leaks after transhiatal and transthoracic oesophagectomy. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of neoadjuvant chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer. Reporting of short-term clinical outcomes after esophagectomy: a systematic review. The 30-day versus in-hospital and 90-day mortality after esophagectomy as indicators for quality of care. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. End-to-end versus end-to-side esophagogastrostomy after esophageal cancer resection: a prospective randomized study. Modern 5-year survival of resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma: single institution experience with 263 patients. Prognostic factors in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction. Prediction of survival in patients with oesophageal or junctional cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery. The number of lymph nodes removed predicts survival in esophageal cancer: an international study on the impact of extent of surgical resection. Surgical resection strategy and the influence of radicality on outcomes in oesophageal cancer. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy for the treatment of esophagogastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiation on lymph node status in esophageal cancer: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. The effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on lymph node harvest after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lymph node retrieval during esophagectomy with and without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: prognostic and therapeutic impact on survival. Multimodality treatment for esophageal adenocaricnoma: multi-center propensity-score matched study. Evolution of standardized clinical pathways: refining multidisciplinary care and process to improve outcomes of the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Salvage surgery after chemoradiotherapy in the management of esophageal cancer: is it a viable therapeutic option Comparing outcomes after transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy: a 5-year prospective cohort of 17,395 patients. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus: five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial. Effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for early-stage esophageal cancer (letter to the editor). Is concurrent radiation therapy required in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus A randomized clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for cancer of the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and the long-term run in curative treatment of locally advanced oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: 58. This article reviews the current indications, techniques, limitations, and outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of esophageal cancer. This approach is a particularly well-suited technique for this tumor, which often does not require a complete esophageal resection, and it is also our preferred option for this disease. A double-lumen endotracheal tube is placed for lung isolation during the thoracoscopic phase. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy is performed to evaluate the proximal and distal extension of the tumor and the presence of Barrett esophagus and to evaluate the stomach, which will be used for reconstruction. As previously described,11 we use five abdominal ports and the Nathanson liver retractor to expose the hiatus. The abdominal cavity and the liver are carefully inspected to rule out any metastatic disease. We start our dissection in the lesser curvature of the stomach by opening the gastrohepatic ligament and exposing the branches of the celiac trunk. This allows exposure and nodal dissection at the base of the celiac artery and the diaphragmatic crus. Mobilization of the greater curvature of the stomach includes complete division of the gastrocolic ligament just distal to the gastroepiploic arcade. Dissection is extended to the fundus by dividing the short gastric vessels and phrenoesophageal attachments and to the proximal duodenum by completely separating the colon from the gastric attachments. When the greater curvature is completely mobilized, the stomach is lifted to dissect the retroperitoneal attachments and mobilize the right gastroepiploic pedicle to its base. Accurate staging is warranted to tailor treatment to the extension of disease, and multimodality treatment is recommended for locally advanced cancers. Surgery is therefore performed approximately 6 to 8 weeks after completion of induction therapy similarly to the open esophagectomy. This operation is, in fact, technically demanding, and a significant learning curve is necessary to limit complications. Improved surgical and oncologic outcomes are usually achieved after 35 to 40 cases. Moreover, several benefits have been reported with minimally invasive surgery over the open approach, such as postoperative pain reduction, faster recovery, and decrease of cardiopulmonary complications, blood loss, and length of stay. The short and long-term oncologic outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy are similar to those observed with open approaches. Minimally invasive esophagectomy is a valid alternative approach to open esophagectomy for both esophageal benign disease and cancer. The left gastric vessels identified in this figure are then divided at their base with an endoscopic stapler. A Kocher maneuver is not routinely performed to avoid conduit redundancy, which may cause herniation of the gastric antrum and duodenum in the mediastinum. After the stomach is completely mobilized, a transhiatal dissection of the esophagus is performed, exposing and carefully removing the paracardial and lower paraesophageal nodes, which are harder to expose from the chest. A Penrose drain is used to encircle the distal esophagus for retraction, and it is left in the mediastinum to help the esophageal dissection during the thoracic phase. Pyloric drainage can be achieved either with pyloromyotomy or with a pyloroplasty. Our preference is to use botulinum toxin (Botox) percutaneously injected into the pylorus in both the gastric and duodenal side. Interrupted Lembert sutures can be used to reinforce the gastric staple line and as a way of measuring conduit length after the conduit has been transposed in the chest. To facilitate retrieval from the chest and avoid torsion, the gastric conduit is left undivided at the fundus. Several studies reported an increase risk of ischemia and leak with a too-narrow diameter (3 to 4 cm) of the gastric tube14; however, leaving the entire stomach can lead to severe regurgitation and offers limited length for chest transposition. Interrupted stitches are used to reinforce the staple line without shortening the conduit and help with gauging conduit length during the thoracic phase. The conduit is left undivided at the fundus to allow easy retrieval from the chest. Insufflation at 8 mm Hg is well tolerated and allows flattening of the diaphragm with easier exposure of the hiatus and stabilization of the mediastinum during dissection.

Generic 10mg zebeta