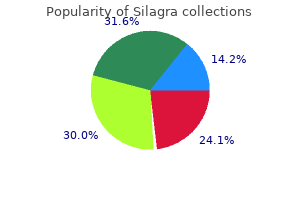

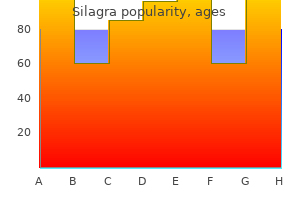

Order 50 mg silagra fast delivery

Schwann cells produce these myelin sheaths and also envelop the unmyelinated axons erectile dysfunction blood flow buy cheap silagra 50 mg. The basal lamina is formed by the Schwann cell and may help stabilize it during the process of myelin formation. At the second level, a distinctive sheath, the perineurium, surrounds each group (fascicle) of axons. A, the inner leaflet of the plasmalemma (red) fuses to form major dense lines, and the outer leaflets (blue) of each adjacent wrap contact each other to form intraperiod lines. B, In an unmyelinated fiber, small axons occupy troughs formed by invaginations of the Schwann cell plasmalemma. C and D, Electron micrographs of a myelinated fiber (C) and an unmyelinated fiber (D) composed of a single Schwann cell supporting more than 20 axons. E, A small myelinated fiber sectioned through part of a SchmidtLanterman cleft reveals the membrane composition of myelin. This arrangement forms a protective blood-nerve barrier against diffusion of substances into peripheral nerve fascicles. Last, the entire peripheral nerve is covered by epineurium, a dense connective tissue sheath of type I collagen and typical fibroblasts. The type called a schwannoma arises singly and, because it is encapsulated and does not include nerve fibers, is easily excised. Neurofibromas are generally difficult to remove because they are unencapsulated and infiltrate nerve bundles. In degenerative diseases, such as Parkinson or Alzheimer disease, death of neurons leads to eventual depopulation of the specific groups of neurons affected. However, if axons are damaged but the cell bodies remain intact, regeneration and return of function can occur in some circumstances. The Cell Biology of Neurons and Glia 33 Peripheral nerve Perineurium Endoneurium Unmyelinated axons Lightly myelinated axons Epineurium Schwann cell: Cytoplasm Basal lamina Heavily myelinated axon A Axon Endoneurium Epineurium Perineurium Basal lamina of perineurial cells Collagen Endocytotic vesicles Axon Collagen the chance of axonal regeneration is best when a peripheral nerve is compressed or crushed but not severed. In milder lesions in which focal demyelination occurs without axonal degeneration (neurapraxia), there is loss of conduction in the nerve, but recovery is expected. When compression or crushing kills the axons distal to the site of injury, the neuronal cell bodies, which are in the spinal cord or in sensory or autonomic ganglia, usually survive. Days to weeks later, axonal sprouting starts at the point of injury, and the axons grow distally. Meanwhile, in the distal part of the nerve, axons die and are removed by macrophages, but the Schwann cells remain. These Schwann cells and basal lamina tubes guide the distally growing axonal sprouts. Macrophages, which have been activated by phagocytosis of myelin debris, signal Schwann cells to secrete nerve growth factor, a neurotrophin that promotes axon growth. Regeneration depends on a variety of influences, including neurotrophins and the basal lamina. In a compression injury (axonotmesis), the proximal axon sprouts and distal bands of Schwann cells remain in their original orientation, so nerve fibers are lined up just as they were before the injury. Therefore, when the axons regenerate, they will find their original positions within the nerve and are more likely to accurately reconnect with their proper targets. When a peripheral nerve is severed (neurotmesis) rather than crushed, regeneration is less likely to occur. Sprouting occurs at the proximal end of the axon, and the axon grows, but it may not reach its distal target. Other axons may fail to enter the Schwann cell tubes, instead ending blindly in connective tissue to form a neuroma. Mechanical or chemical stimulation of these blindly ending sensory axons may be the cause of "phantom pain" in persons with amputated limbs. Astrocytes hypertrophy and proliferate at the site of injury and fill any space left by the injury or by degeneration of the damaged nerve tissue. The responding astrocytes grow in a random orientation and form a scar rather than a pathway. Furthermore, astrocytes may not secrete adequate growth factors to sustain regrowing axons. The astrocytic scar appears to be a barrier rather than a guidance mechanism for axonal sprouts. Moreover, specific molecules present in oligodendrocyte-derived myelin may also inhibit axonal regrowth. The axonal sprouts are eventually retracted, and the loss of function associated with the severed pathway is permanent. B, An electron micrograph corresponding to the area enclosed by the box in A reveals ultrastructural elements characteristic of each of the three sheaths. Visualization of oligodendrocytes and astrocytes in the intact rat optic nerve by intracellular injection of Lucifer yellow and horseradish peroxidase. Neuronal-astrocytic interactions in brain development, brain function and brain disease. This article begins with a discussion of the fundamental electrical and chemical properties of the solutions of small ions and large proteins that comprise the interior of the cell and its environs and shows how a neuron uses those forces to ensure its own integrity-and how bacteria and our own immune system broach these defenses to destroy neurons. Next are the electrical properties of the nerve that allow us to sense our environment and to integrate neural data. These impermeant molecules exert an osmotic force that draws water into the cell, causing it to swell and ultimately to burst unless an opposing force intervenes first. As a result, the very first task of the cell is to ensure its own physical integrity, both by minimizing osmotic flow of water and by removing that excess water that does enter the cell. Forces Due to Concentration Gradients Membranes composed of a lipid bilayer enclose all cells in the body as well as all the organelles within those cells. Being lipid, these membranes are impermeant to small ions and macromolecules alike. A variety of transport proteins, selected from among hundreds available in the genome (Table 3. Any solute added to water takes up space, displacing water molecules and so reducing their concentration. Since all substances spontaneously tend to move from regions of a higher concentration to regions of a lower concentration, water will tend to move into the cell from the interstitium, causing the cell to swell. Maintenance of proper cell volume is so important that a variety of systems have evolved to counter the presence of cell proteins and to adjust to changing interstitial conditions. Indeed, pathologists generally see abnormal swelling in metabolically compromised cells, when the processes that counter this tendency are no longer adequately functioning. Individual channels are grouped into families and then into superfamilies on the basis of structural homologies. These channels may be open constitutively; be regulated by membrane voltage, by cell calcium, or by second messengers; or be signaled to open by synaptic transmitters. The narrowest part of the channel excludes larger molecules; the inner structure has a high dielectric that effectively substitutes for bulk water, allowing single water molecules to corkscrew through the channel. Osmotic forces measure the tendency of water to move down its concentration gradient, but our analytic instruments measure the solutes (sodium, potassium, chloride, sucrose-the dissolved substance), not the water. As a result, we dissemble when we say that osmotic forces tend to move water from a more dilute solution (of solute, that is) to a more concentrated one. In truth, the higher concentration of water is in the solution that has the lower concentration of solute, and water does in fact move as required by the laws of entropy, namely, from the solution of higher (water) concentration to the solution of lower (water) concentration. Cells counter the osmotic force exerted by the high intracellular concentrations of protein by making a predominantly extracellular particle (sodium) impermeant as well. Consequently, sodium is generally more concentrated outside the cell (extracellular) than inside the cell (intracellular) (Table 3. The osmotic force (for pressure) exerted by this one ionic gradient is huge, being proportional to the difference between the two concentrations (Table 3. The adjustments available to the cell that correct for small imbalances are the topic of the next section. Electrical Forces Cell proteins generally carry negative charges, and this large quantity of impermeant charge has important electrical consequences.

Generic silagra 100mg line

Midline lesions may also result in a tremor of the axial body or head called titubation male erectile dysfunction pills review silagra 100mg free shipping. This tremor can range in amplitude from barely noticeable to so powerful that the patient is unable to sit or stand unsupported. Nystagmus is frequently seen, and deficits in pursuit eye movements are also common. For example, lateral portions of the vermal cortex receive secondary vestibulocerebellar fibers and project to the ipsilateral vestibular nuclei. Consequently, the fastigial nucleus links vestibulocerebellar cortex and portions of the vermal cortex with the vestibular and reticular nuclei of the brainstem. In this respect, the vermal cortex and fastigial nucleus share the task of influencing axial musculature along with vestibulocerebellar and spinocerebellar modules. Spinocerebellar Module the vermal and intermediate zones receive input mainly via the posterior and anterior spinocerebellar tracts and, from the upper extremity, through cuneocerebellar fibers. Fibers that enter the vermal zone send collaterals into the fastigial nucleus, and those passing into the intermediate zone send branches into the emboliform and globose nuclei. The output of the spinocerebellum is focused primarily on the control of axial musculature through vermal cortex and fastigial efferents and on the control of limb musculature through efferents of the globose and emboliform nuclei. Posterior spinocerebellar and cuneocerebellar fibers inform the cerebellum of limb position and movement. Cells in the spinal cord that give rise to anterior spinocerebellar fibers receive primary sensory inputs and are also under the influence of descending reticulospinal and corticospinal fibers. In this respect, anterior spinocerebellar fibers provide afferent signals and feedback to the cerebellum about motor circuits in the spinal cord. These arise in the contralateral accessory olivary nuclei (olivocerebellar fibers), the vestibular nuclei (secondary vestibulocerebellar fibers), the contralateral pontine nuclei (pontocerebellar fibers), and the reticular nuclei (reticulocerebellar fibers). These afferent axons also send collaterals into the fastigial and interposed nuclei. Corticonuclear fibers project in a topographic sequence into their respective nuclei on the ipsilateral side. For example, fibers from anterior parts of the vermis enter rostral portions of the fastigial nucleus, whereas those of the posterior vermis project into caudal areas of the same nucleus. In general, this pattern is repeated between the intermediate zone and the emboliform and globose nuclei. As indicated previously, the fastigial nucleus projects bilaterally to vestibular and reticular nuclei, which, through their spinal projections, influence axial muscles. These particular thalamic neurons project mainly to areas of the primary motor cortex. Other globose and emboliform efferents travel caudally to terminate in the reticular formation (cerebelloreticular fibers) and in the inferior olivary complex (cerebelloolivary fibers). Reticular cells influence spinal motor neurons and project back to the spinocerebellum as reticulocerebellar fibers. Damage to spinocerebellar structures is frequently the result of extension from more medially or laterally located lesions. Consequently, the clinical picture is dominated by deficits characteristic of these medial or lateral regions. Because the pontine nuclei receive a major projection from the ipsilateral cerebral cortex (as corticopontine fibers), this lateral zone is sometimes called the cerebrocerebellum (or neocerebellum). However, the term pontocerebellum is more appropriate and is in parallel with vestibulocerebellum and spinocerebellum. The pontocerebellum functions in the planning and control of precise dexterous movements of the extremities, particularly in the arm, forearm, and hand, and especially in the timing of these movements. Through its connections to motor cortical areas, the dentate nucleus is capable of modulating activity in cortical neurons that project to the contralateral spinal cord. They enter the cerebellum via the restiform body, send collaterals to the dentate nucleus, and end in the molecular layer as climbing fibers. As for other cerebellar regions, corticonuclear fibers of the lateral zone are topographically organized; rostral and caudal areas of the zone project to the corresponding portions of the dentate nucleus. Some neurons of the parvocellular red nucleus project, as components of the central tegmental tract, to the ipsilateral inferior olivary complex (rubroolivary fibers). Descending crossed projections from the dentate nucleus pass mainly to the principal olivary nucleus (dentatoolivary fibers) and, in limited numbers, to the reticular and basilar pontine nuclei. Olivocerebellar fibers arising in the principal nucleus cross the midline and distribute to the cortex of the lateral zone and to the dentate 410 Systems Neurobiology nucleus. There is also feedback to the dentate nucleus via pontocerebellar and reticulocerebellar fibers. The relationship between the dentate nucleus and movement has been explored experimentally. A cooling probe implanted in the cerebellar white matter adjacent to the dentate nucleus halts most of the electrical activity in dentate neurons. This significant reduction in electrical signals temporarily disconnects the dentate nucleus from its targets without permanently destroying the nucleus. As a result of the delay of excitatory output from the motor cortex, there are corresponding delays in muscle contraction. For example, the initial activation of an agonist muscle (biceps brachii) to a load is slowed and its overall contraction time is longer. Similarly, the activation of the antagonist muscle (triceps brachii) that occurs when the load is removed is also delayed. Furthermore, the reciprocal pattern of activation in agonists and antagonists that accompanies some movements is dramatically disrupted. Thus, as well as influencing the duration of muscle contraction, cerebellar output is involved in timing of muscle activation (and inactivation). Note that as the patient moves his finger closer to the target (his nose), the tremor becomes worse. In other words, as the patient "intends" to make a precise movement, the tremor becomes progressively worse as the target is approached; this sequence of events is an easy way to remember this deficit. Pontocerebellar Dysfunction Before the consequence of lesions affecting the pontocerebellar module is considered, two important points merit emphasis. First, damage that involves only the cerebellar cortex rarely results in permanent motor deficits. However, damage to the cortex plus nuclei or to only the nuclei results in a wide range of motor problems that may have long-term consequences. Second, lesions of the cerebellar hemisphere result in motor deficits on the ipsilateral side of the body because the motor expression of cerebellar injury is mediated primarily through corticospinal and rubrospinal pathways. In brief, the right lateral and interposed nuclei influence the left motor cortex (through the ventral lateral nucleus) and the left red nucleus, both of which in turn project to the right side of the spinal cord. Thus a lesion in the cerebellum on the right results in deficits on the right side of the body. The exceptions are a midline lesion and a lesion distal to the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle that may result in cerebellar signs and symptoms. The midline lesion produces bilateral deficits restricted to axial or truncal parts of the body, whereas the lesion distal to the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle results in deficits on the side opposite the lesion. Lesions that involve the cerebellar hemisphere frequently affect portions of the lateral and intermediate modules. It is common for these disorders to be categorized as disorders of the lateral (or hemisphere) zone or as neocerebellar disorders. In general, lesions of the lateral cerebellum result in a deterioration of coordinated movement, which is sometimes referred to as a decomposition of movement (or dyssynergia). This deficit consists of the breakdown of movement into its individual component parts. There may also be a decrease in muscle tone (hypotonia) and in deep tendon reflexes. Ataxia involving the extremities generally is also seen in patients with lateral cerebellar lesions. Because of ataxia of the lower extremity, these patients may also have an unsteady gait and a tendency to lean or to fall to the side of the lesion. Dysmetria (also called past-pointing) is apparent in patients when they attempt to point accurately or rapidly to moving or stationary targets.

Buy silagra 100 mg low price

Polar temporal and anterior arteries are branches of M1; the remaining arteries represent branches of M4 erectile dysfunction vitamin b12 silagra 100mg generic. Branches from M1 serve adjacent medial and rostral aspects of the temporal lobe and, via lenticulostriate arteries, the basal nuclei located inside the cerebral hemisphere. Whereas it is common to refer to the lenticulostriate arteries (plural), in about 40% of patients, this vessel originates as a single trunk that immediately divides into a number of branches (the arteries) that penetrate the hemisphere. The other patterns are two main trunks (30%) that immediately divide, and 10 to 15 small arteries (30%) arising directly from M1. These trunks and their distal branches collectively serve the insular cortex, the inner aspects of the opercula, and the lateral surface of the cerebral hemisphere. Distal branches of the superior and inferior trunks exit the lateral fissure and serve, respectively, cortical areas located above and below this fissure. M4 branches serve trunk, upper extremity, and face areas of the somatomotor and somatosensory cortex; occlusion of these vessels may produce somatomotor and/or somatosensory deficits affecting these body regions on the contralateral side. This portion of the cerebrovascular system is the primary source of blood supply to the brainstem. The second segment, V2, is that portion of the vertebral artery that ascends through the transverse foramina of C6 to C2. Once it is inside the subarachnoid space, the vertebral artery is located in the lateral cerebellomedullary cistern. The vertebral artery supplies the anterolateral medulla and, just before joining its counterpart on the opposite side, gives rise to the anterior spinal artery. In procedures in the posterior fossa, the distal two segments may be sacrificed, but the proximal three must be preserved. These arteries may penetrate the pons immediately as paramedian branches, travel for a short distance around the pons as short circumferential branches, or pass for longer distances as long circumferential branches. The last major branches of the basilar artery are the superior cerebellar arteries. These vessels pass laterally just caudal to the root of the oculomotor nerve and wrap around the brainstem in the ambient cistern to ultimately serve caudal parts of the midbrain and the entire superior surface of the cerebellum. P4 branches, particularly the calcarine artery, serve the primary visual cortex; occlusion of these vessels will likely result in a homonymous hemianopia of the opposite visual fields. Smaller border zones are also located between the territories of the anterior and posterior cerebral arteries at the parietooccipital sulcus and between the territories of the cerebellar arteries. The brain tissue located in these border zones is particularly susceptible to damage under conditions of sudden systemic hypotension or when there is hypoperfusion of the distal vascular bed of a major cerebral artery. Such lesions represent about 10% of all brain infarcts and may be caused by, for example, hypotension or embolic showers. This loop of vessels passes around the optic chiasm and the optic tract, crosses the crus cerebri of the midbrain, and joins at the pons-midbrain junction. The anteromedial group originates from A1 and from the anterior communicating artery. These vessels serve structures in the area of the optic chiasm and anterior parts of the hypothalamus. Included in this group are the lenticulostriate arteries, which serve the interior of the hemisphere. Vessels of the anterolateral group enter the hemisphere via the anterior perforated substance. These vessels supply the crus cerebri and the middle and caudal portions of the hypothalamus and enter the interpeduncular fossa via the posterior perforated substance. The thalamoperforating arteries are part of the posteromedial group, and as their name implies, they serve the thalamus. The distal territories of these vessels overlap at their peripheries and create watershed zones. These zones are susceptible to infarcts (C) in cases of hypoperfusion of the vascular bed. Small border zones also exist (A) between superior cerebellar (green) and anterior inferior (blue) cerebellar arteries. Anterior cerebral artery (A1) Middle cerebral artery (M1) Hypothalamus the superficial middle cerebral vein. The venous blood in these channels and from the corpus callosum and the interior of the hemisphere (internal cerebral veins) drains into the great cerebral vein (of Galen) and then into the straight sinus. Rather than a true confluence, the superior sagittal sinus usually drains into the right transverse sinus and the straight sinus into the left. The major venous sinuses are endothelium-lined channels in the meningeal reflections. The superior and inferior sagittal sinuses are located in the attached and free edges of the falx cerebri, respectively. The straight sinus is found where the falx cerebri attaches to the tentorium cerebelli. The other venous sinuses are located adjacent to the inner surface of the skull at specific locations. These large anastomotic veins form channels between the superior sagittal and transverse sinuses and the basal vein (of Rosenthal) begins on the orbital cortex as the anterior cerebral vein and in the sylvian fissure as the deep middle cerebral vein and proceeds around the medial edge of the temporal lobe to join the straight sinus. The transverse and sigmoid sinuses form a shallow groove on the internal surface of the occipital and temporal bones, respectively, and receive several tributaries. These nerves are found internal to the dura surrounding the sinus but are external to its endothelial lining. Caudally, the cavernous sinus drains into the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses and the basilar plexus on the ventral aspect of the brainstem. For clarity, the petrosal sinuses are shown only on the left and the basal vein (of Rosenthal) only on the right. An expanding aneurysm will affect the adjacent nerves, resulting in a partial or complete paralysis of eye movement, loss of the corneal reflex, and paresthesias or pain within the distribution of the ophthalmic and maxillary nerves. An aneurysm of the cavernous part of the carotid artery (B) will damage some or all of the cranial nerves passing through the sinus. The patient was shot in the face, the bullet (B) entering the orbit and damaging the internal carotid artery in the cavernous sinus. Note that the radiopaque substance injected into the common carotid artery appears in the anterior and middle cerebral arteries and internal jugular vein before appearing in the veins and sinuses of the head. This means that some blood is passing from the internal carotid artery into the cavernous sinus and then directly into the internal jugular vein. Of these, the superior thalamostriate vein (also called the terminal vein) merits comment. It is found in association with the stria terminalis and drains the caudate nucleus (via the transverse caudate veins) and internal regions of the hemisphere dorsal and lateral to the caudate nucleus. Consequently, pathologic processes may alter normal venous flow patterns and result in the transport of material into the brain. Posterior cerebral artery Vein of Galen malformation Bulging fontanelles, progressive hydrocephalus (resulting from occlusion of the cerebral aqueduct), and dilated veins in the face and scalp are characteristic findings. Brainstem and Cerebellum the brainstem is drained by a loosely organized network of venous channels located on its surface. In general, these vessels enter larger veins or venous sinuses located in the immediate vicinity. For example, veins of the midbrain enter the great cerebral and basal veins, whereas those of the pons and medulla may enter the petrosal sinuses and the cerebellar veins. The superior cerebellar veins enter the straight, transverse, or superior petrosal sinuses. The inferior cerebellar surface is drained by inferior cerebellar veins, which enter the inferior petrosal, transverse, or straight sinuses. For example, a tumor or infection in the orbit may cause venous blood to flow toward the cavernous sinus rather than away from it. In this way, infectious material or tumor cells may pass from the orbit into the cavernous sinus and, through its connecting channels, to other parts of the brain. In these cases, the great cerebral vein is grossly enlarged and fed by large and abnormal branches of the cerebral and cerebellar arteries. The veins involved are usually the larger ones, such as the superficial veins on the cerebral cortex or the internal cerebral veins. On the other hand, cerebral venous thrombosis may occur after brain surgery, meningitis, sinus infections, traumatic head injuries, or gunshot injury to the head, especially those that may involve the sinuses. The occlusion of a venous structure reduces or blocks venous return and results in a cascade of events.

Order silagra on line

Common intraventricular sites of potential obstruction are the interventricular foramen (or foramina) erectile dysfunction causes and solutions cheap silagra 100mg overnight delivery, cerebral aqueduct, caudal portions of the fourth ventricle, and foramen of the fourth ventricle. Extraventricular obstruction may occur at any place in the subarachnoid space but is more common around the base of the brain, at the tentorium cerebelli and tentorial notch, over the convexity of the hemisphere, and at the superior sagittal sinus. Aqueductal Stenosis Aqueductal stenosis may be caused by a tumor in the immediate vicinity of the midbrain (as in pineoblastoma or meningioma) that compresses the brain and occludes the cerebral aqueduct. This is sometimes called triventricular hydrocephalus because the three ventricles upstream to the blockage simultaneously enlarge as a result of one lesion or occlusion. Unilateral obstruction of one interventricular foramen, for example, by a colloid cyst in one interventricular foramen, results in enlargement of the lateral ventricle on that side. Blockage of both interventricular foramina will produce enlargement of both lateral ventricles. Obstruction of the exit channels of the fourth ventricle, the foramina of Magendie and Luschka, will result in enlargement of all parts of the ventricular system. This block may be caused by a congenital absence (agenesis) of the arachnoid villi. Alternatively, these villi may be partially blocked by red blood cells subsequent to a subarachnoid hemorrhage. In all of these situations, there is an enlargement of all parts of the ventricular system. Although rare, hydrocephalus may also be seen in patients with impaired venous flow from the brain. There is no increase in intracranial pressure, there are no neurologic deficits other than those that may be related to brain atrophy, and treatment is not indicated. Ex vacuo changes may also refer to atrophy with a change in ventricular size that may follow, by several years, an event such as a stroke. Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) is an enigmatic condition most commonly seen in obese women of childbearing age. These patients usually experience headache, tinnitus due to venous turbulence ("pulsatile intracranial noise"), and visual deficits (up to blindness) due to papilledema (swelling of the optic disc). Treatment includes a program of weight loss, medication, and, if needed, shunting (lumboperitoneal) or surgical fenestration of the optic nerve sheath, which consists of making a window in the sheath to relieve pressure on the optic nerve. Although intracranial pressure may initially be elevated and the ventricles enlarged, the pressure may wax and wane over time or even subside to a high-normal level; however, the effects of the increased pressure remain. In some patients, the combination of a difficult shuffling gait and dementia may mimic the clinical picture in neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. In some cases, there is general clinical improvement with lessening of all symptoms. A light and electron microscopic and immunohistochemical study of human arachnoid villi. Integration of the subarachnoid space and lymphatics: is it time to embrace a new concept of cerebrospinal fluid absorption The morphology of cerebrospinal fluid drainage pathways in human arachnoid granulations. Functional ultrastructure of cerebrospinal fluid drainage channels in human arachnoid villi. Haines Overview-107 Development of the Meninges-107 Overview of the Meninges-108 Dura Mater-109 Periosteal and Meningeal Dura-109 Dural Border Cell Layer-109 Blood Supply-110 Nerve Supply-110 Dural Infoldings and Sinuses-110 Compartments and Herniation Syndromes-111 Cranial Versus Spinal Dura-112 Arachnoid Mater-112 Arachnoid Barrier Cell Layer-112 Arachnoid Trabeculae and the Subarachnoid Space-113 Arachnoid Villi-113 Meningioma-114 Origins and Locations-114 General Histologic Features-114 Symptoms and Treatment-115 Meningeal Hemorrhages-116 Extradural and "Subdural" Hemorrhages-116 Hygroma-116 Pia Mater-116 Cisterns, Subarachnoid Hemorrhages, and Meningitis-118 maximum protection, they can be very unforgiving in the case of trauma or in a disease process. For example, growth of a tumor creates a mass that may increase intracranial pressure and compress or displace various portions of the brain. Something has to give inside the skull when a space-occupying lesion develops, and it is the delicate tissue of the brain that gives. The neurologic deficits that result depend on the location of the mass, the rapidity with which it enlarges, and which parts of the brain are damaged. Collectively, these neural crest and mesodermal cells form the primitive meninges (meninx primitiva). At this stage, no obvious spaces (venous sinuses, subarachnoid space) are present in the meninges. As development progresses (45 to 60 days of gestation), the ectomeninx becomes more compact, and spaces appear in this layer that correlate with the positions of the future venous sinuses. Concurrently, the endomeninx becomes more reticulated, and the spaces that appear in its inner part correspond to the subarachnoid spaces and cisterns of the adult. By the end of the first trimester, the general plan of the meninges is established. This defect is caused by a failure of the ectoderm (future skin) to completely pinch off from the neuroectoderm and the primitive meninges that envelop it. Dermal sinuses are sometimes discovered in young patients who have recurrent but unexplained bouts of meningitis. The ectomeninx around the brain is continuous with the skeletogenous layer that forms the skull. This relationship is maintained in the adult, in whom the dura is intimately adherent to the inner surface of the skull. In the spinal column, the ectomeninx is also initially continuous with the developing vertebrae. However, as development proceeds, the spinal ectomeninx dissociates from the vertebral bodies. A layer of cells remains on the vertebrae to form the periosteum lining the vertebral canal, and the larger part of the ectomeninx condenses to form the spinal dura. In the vertebral column, this space may be used for the administration of epidural anesthetics. For protection, the brain and spinal cord are each encased in a bony shell, enveloped by a fibrous coat, and delicately suspended within a fluid compartment. In the living state, the nervous system has a gelatinous consistency, but when treated with fixatives, it becomes firm and easy to handle. With the exception of the intervertebral foramina, through which the spinal nerves and their associated vessels pass, and the foramina in the skull, which serve as conduits for arteries, veins, and cranial nerve roots, this bony encasement is complete. The meninges (1) protect the underlying brain and spinal cord; (2) serve as a support framework for important arteries, veins, and sinuses; and (3) enclose a fluid-filled cavity, the subarachnoid space, that is vital to the survival and normal function of the brain and spinal cord. After the neural tube closes (A and B), cells from the neural crest and mesoderm (C, arrows) migrate to surround the neural tube and form the primordia of the dura and of the arachnoid and pia (D). A dermal sinus (E) is a malformation in which there is a channel from the skin into the meninges. The fibroblasts of each meningeal layer are modified to serve a particular function. Layers of the dura are shown in shades of gray, the arachnoid in shades of pink, and the pia in green. This term is also commonly used in clinical medicine (as in leptomeningeal cysts and leptomeningitis). Meningeal infections are frequently sequestered in the subarachnoid space; hence they are within the leptomeninges. The arachnoid is a thin cellular layer that is attached to the overlying dura but, with the exception of the arachnoid trabeculae, is separated from the pia mater by the subarachnoid space. Consequently, the spinal and cerebral subarachnoid spaces are also directly continuous with each other at the foramen magnum. Fibroblasts of the periosteal dura are larger and slightly less elongated than other dural cells. This portion of the dura is adherent to the inner surface of the skull, and its attachment is particularly tenacious along suture lines and in the cranial base. In contrast, the fibroblasts of the meningeal dura are more flattened and elongated, their nuclei are smaller, and their cytoplasm may be darker than that of periosteal cells. Although cell junctions are rarely seen between dural fibroblasts, the large amounts of interlacing collagen in periosteal and meningeal portions of the dura give these layers of the meninges great strength. The innermost part of the dura is composed of flattened fibroblasts that have sinuous processes. The extracellular spaces between the flattened cell processes of dural border cells contain an amorphous substance but no collagen or elastic fibers.

Order silagra 100 mg online

The sensory fiber erectile dysfunction when young cheap silagra 50mg with amex, the associated motor neuron, and the resultant involuntary muscle contraction constitute the circuit of the spinal reflex. Reflexes are essential to normal function and are widely used as diagnostic tools to assess the functional integrity of the spinal cord. Fourth, the spinal cord contains descending fibers that influence the activity of spinal neurons. These fibers originate in the cerebral cortex and brainstem, and damage to them adversely influences the activity of spinal motor and sensory neurons. In many cases, the position of a lesion in the brainstem or spinal cord may give rise to a predictable or characteristic series of deficits, such as in decorticate rigidity or an alternating hemianesthesia. Fifth, injury to peripheral nerves will result in motor or sensory deficits distal to the lesion. These are most noticeable in the extremities and may be manifested as motor deficits (flaccid paralysis), a significant decrease or loss of essential spinal reflexes (hyperreflexia, hyporeflexia, areflexia), a loss of sensation (anesthesia), or abnormal sensations (paresthesia). Cross-sectional (A) and dorsal (B) views of the neural plate and the correlation of neural tube structures with the adult cord (C). The white area between the blue (posterior horn) and pink (anterior horn) of the adult spinal cord represents the approximate position of the intermediate gray. Malformations involving defects of the nerve tissue or surrounding bone include rachischisis (D), meningocele (E, solid cord) or meningomyelocele (E, dashed cord), and anencephaly with rachischisis (F). The neural plate gives rise to the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar levels, whereas the caudal eminence gives rise to the sacral and coccygeal levels. By 20 days of gestation, the neural plate is an oblong structure that is larger at its rostral area (future brain) and tapered caudally (future spinal cord). The initial apposition of the neural folds to form the neural tube takes place at what will become, in the adult, cervical levels of the spinal cord. This closure simultaneously proceeds in rostral and caudal directions, ultimately creating small openings at either end between the cavity of the neural tube and the surrounding amniotic cavity. These openings are the anterior and posterior neuropores; they close at 24 and 26 days of gestation, respectively. Neural Tube the portion of the neural tube that will differentiate into the spinal cord initially consists of the ventricular zone and the marginal zone (see Chapter 5). The ventricular zone contains cells, neuroblasts, and glioblasts that are undergoing mitosis and the precursor cells that will form the ependymal cell layer lining the central canal. The marginal zone is initially narrow and contains the processes of cells of the ventricular zone but does not contain their cell bodies or nuclei. After their final cell division, postmitotic neurons and glial cells migrate outward to form the intermediate zone. This establishes the basic three-layered structure-ventricular zone, intermediate zone, and marginal zone-of the neural tube. As development progresses, the intermediate zone enlarges, and the processes arising from the maturing neurons of this zone enter the marginal zone. The neural crests detach from the lateral edge of the neural plate and assume a location anterolateral to the neural tube. Neural crest cells differentiate into cells of the posterior root ganglia, among other structures. The intermediate zone (the term preferred instead of mantle zone) contains columns of maturing neurons, forming the paired alar plates posteriorly and the paired basal plates anteriorly. Maturing neurons of the alar plate differentiate into the tract neurons and interneurons of the posterior horn of the adult, and those of the basal plate become motor neurons and interneurons of the anterior horn. These axons, most of which become myelinated, form the various tracts of the white matter of the adult spinal cord. Rachischisis occurs when the neural folds do not join at the midline and the undifferentiated neuroectoderm remains exposed. In its extreme form, rachischisis totalis (or holorachischisis), the entire spinal cord remains open. Rachischisis partialis (or merorachischisis) is the situation in which the spinal cord is partially closed and partially flayed open. A failure of the anterior neuropore to close results in a failure of the skull and the underlying brain to properly develop. Rachischisis and meroanencephaly are catastrophic developmental defects that in most cases (particularly the latter) are not compatible with life. In other cases, the neural tube may develop normally, but the surrounding vertebrae may not form properly, resulting in spina bifida occulta or spina bifida cystica. Spina bifida occulta is characterized by partially missing vertebral arches; the area of the defect may be indicated by a patch of dark hairs. Spina bifida cystica is seen as enlargements that may contain only meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (meningocele) or meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, and portions of the spinal cord (meningomyelocele). Surface Features the human spinal cord extends from the foramen magnum to the level of the first or second lumbar vertebra. Although it is generally cylindrical, the cord has cervical (C4 to T1) and lumbosacral (L1 to S2) enlargements, which serve, respectively, the upper and lower extremities. These enlargements serve to accommodate the pools of large lower (alpha) motor neurons in these respective cord levels. There are eight cervical roots (and spinal cord levels) but only seven cervical vertebrae. Therefore roots C1 through C7 are located above (rostral to) their respectively numbered vertebrae, and the C8 root is located between the C7 and T1 vertebrae. The posterior median sulcus separates the posterior portion of the cord into halves and contains a delicate layer of pia, the posterior median septum. The posterolateral sulcus, which runs the full length of the cord, represents the entry point of posterior root (sensory) fibers. In cervical and upper thoracic regions, a posterior intermediate sulcus and septum are found between the posterolateral and posterior median sulci. Because of the organization of the gracile and cuneate fasciculi, the posterior intermediate septum is present only in upper thoracic and cervical cord levels. Because the anterior roots exit in a somewhat irregular pattern, this sulcus is not as distinct as the posterolateral sulcus. The spinal cord, in turn, is attached to the dural sac by the laterally placed denticulate ligaments and by the filum terminale internum. This latter structure extends caudally from the end of the spinal cord, the conus medullaris, and terminates in the attenuated (closed) portion of the dural sac, which is located adjacent to the S2 vertebra. The arachnoid mater adheres to the inner surface of the dura mater, and the pia mater is intimately attached to the surface of the cord. Note that the lateral corticospinal tract and the anterolateral system receive a dual blood supply; also note the topographic arrangement of corticospinal fibers. The anterior white commissure is located on the anterior midline and is separated from the central canal by a narrow band of small cells. The posterolateral tract, the tract of Lissauer, is a small bundle of lightly myelinated and unmyelinated fibers capping the posterior horn. The gray matter of the spinal cord is composed of neuron cell bodies, their dendrites and the initial part of the axon, the axon terminals of fibers synapsing in this area, and glial cells. The spinal gray matter is divided into a posterior (dorsal) horn, an anterior (ventral) horn, and the region where these meet, commonly called the intermediate zone (or intermediate gray). In his original, and detailed, description of the spinal laminae (1952, 1954), Rexed specifically named this latter region area X and not lamina X, a term frequently used. In adults the conus medullaris is located at the level of the L1 or L2 vertebral body. This cistern contains the posterior and anterior roots from spinal segments L2 to Coc1 as they sweep caudally. White Matter the white matter of the spinal cord is divided into three large regions, each of which is composed of individual tracts or fasciculi. At cervical levels, this area consists of the gracile and cuneate fasciculi; collectively, these are commonly referred to as the posterior (dorsal) columns. There is a large amount of white matter because a full complement of ascending and descending fiber tracts is present.

Purchase silagra pills in toronto

In the spinal cord erectile dysfunction over 60 buy silagra discount, the posterior part of the ventricular zone and adjacent intermediate zone become the alar cell columns or alar plate, which will differentiate into the posterior horn. The corresponding layers in the anterior part of the developing neural tube become the basal cell columns or basal plate, which will differentiate into the anterior horn. As development proceeds, the ventricular zone will essentially disappear, while the intermediate zone with its maturing neurons will progressively enlarge to form the adult derivatives. Consequently, the adult derivatives are the products of cell division in the ventricular zone, migration and formation of the intermediate zone, and maturation within this intermediate zone. The development of the alar and basal plates, and then the subsequent posterior and anterior horns, is a dynamic process. The cortical plate forms at the interface of the marginal zone and the intermediate zone and is composed of neurons that originate from the ventricular zone. These postmitotic immature neurons traverse the intermediate zone, using the radially oriented processes of radial glia as a scaffold to become the cortical plate. Cell migration on radial glia is characteristically seen in all portions of the developing nervous system. The subplate is a narrow region located immediately internal to the cortical plate. The histogenesis of the cerebellar cortex is a slight modification of the cerebral cortex plan due to the presence of an external germinal layer. This external germinal layer originates from the rhombic lip, an alar plate derivative, and is located within the marginal layer. It defines the longitudinal axis of the embryo, determines the orientation of the vertebral column, and persists as the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disks. Associated with this process is the production of cell adhesion molecules in the notochord. These molecules diffuse from the notochord into the neural plate and function to join the primitive neuroepithelial cells into a tight unit. Within the neuroectoderm, some neuroepithelial cells elongate and become spindle shaped. Most of the neural tube forms from the neural plate by a process of infolding called primary neurulation. This part of the neural tube will give rise to the brain and to the spinal cord through lumbar levels. The most caudal portion of the neural tube, which will give rise to sacral and coccygeal levels of the cord, is formed by a process called secondary neurulation. This thickening A Ventricular zone Marginal zone Ventricular zone B Intermediate zone Marginal zone Subventricular zone Ventricular zone Intermediate zone elevates the edges of the neural plate to form neural folds. At about 20 days, the neural folds first contact each other to begin the formation of the neural tube. The rostral opening, the anterior neuropore, closes at about 24 days, and the caudal opening, the posterior neuropore, closes about 2 days later. Neurulation is brought about by morphologic changes in the neuroblasts, the immature and dividing future neurons in the ventricular zone. As mentioned previously, these cells are elongated and are oriented at right angles to the dorsal surface of the neural plate, which will be the inner wall of the neural canal. Microfilaments in each cell form a circular bundle parallel to the future luminal surface, whereas microtubules extend along the length of the cell. The contraction of the circular bundle of microfilaments causes the microtubules to splay out like the rays of a fan. This forms an elongated conical cell with its apex at the neural groove and its base at the edge of the neural fold. Neurulation does not occur in embryos exposed to colchicine, which depolymerizes microtubules, or to cytochalasin, which inhibits microfilamentbased contraction. Congenital malformations associated with defective neurulation are called dysraphic defects. The process of induction also means that the proper development of a structure is dependent on the proper development of its neighbors. There is an intimate relationship of neural tissue to the surrounding bone, meninges, muscles, and skin. Because of this relationship, a failure of neurulation often impairs the formation of these surrounding structures. Several well-controlled clinical trials have proven that supplementation with the vitamin folic acid can reduce the incidence of neural tube defects. In the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study, carried out in Great Britain and published in 1991, women who had previously been delivered of a child with a dysraphic defect were assigned to either a folic acid supplementation group or a control group during a subsequent pregnancy. Folic acid supplementation reduced the incidence of neural tube defects by about 70% relative to that in untreated controls. Dysraphic defects have also been observed in infants born to mothers who had circulating antibodies to the folate receptor. Department of Agriculture has established a Recommended Daily Allowance for folic acid supplementation of 600 g/day before and during pregnancy. In addition, drugs taken for epilepsy, such as valproic acid and carbamazepine, can cause dysraphic defects. Rostral to the spinal cord, the developing neural tube differentiates in a more complex manner (D) to accommodate more complex structures such as the cerebellar and cerebral cortices. Most dysraphic disorders occur at the location of the anterior or posterior neuropore. In this defect, the brain is not formed, the surrounding meninges and skull may be absent, and there are facial abnormalities. The defect extends from the level of the lamina terminalis, the site of anterior neuropore closure, to the region of the foramen magnum. Encephaloceles are most common in the occipital region, but they may also occur in frontal and parietal locations. This defect may go unnoticed until early adulthood and is often associated with a cavitation of the spinal cord (syringomyelia) or of the medulla (syringobulbia). Defects in the closure of the posterior neuropore cause a range of malformations known collectively as myeloschisis. The defect always involves a failure of the vertebral arches at the affected levels to form completely and fuse to cover the spinal cord (spina bifida). If the skin is not closed over the vertebral defect, leaving a patent aperture, the malformation is called spina bifida aperta. In the latter case, the neural tissue may be the lower part of the spinal cord or, more commonly, a portion of the cauda equina. Infants with meningomyelocele may be unable to move their lower limbs or may not perceive pain sensations from skin innervated by nerves passing through the lesioned area. A cell mass, the caudal eminence, appears just caudal to the neural tube and then enlarges and cavitates. The caudal eminence joins the neural tube, and its cavity becomes continuous with the neural canal. Magnetic resonance image of meningohydroencephalocele (A) and drawings of meningocele (B), meningoencephalocele (C), and meningohydroencephalocele (D). The malformation is covered with skin in most cases, but the site may be marked by unusual pigmentation, hair growth, telangiectases (large superficial capillaries), or a prominent dimple. A common abnormality is tethered cord syndrome, in which the conus medullaris and filum Pons Syringobulbia terminale are abnormally fixed to the defective vertebral column. The sustained traction damages the spinal cord and causes variable weakness, sensory loss and asymmetric growth of the legs and feet, and problems with bowel and bladder control. Infants born to mothers with diabetes mellitus can have caudal regression syndrome, which affects the development of the embryonic structures in the caudal region including the spinal cord. Primary Brain Vesicles Occipital bone Cerebellum in foramen magnum Spinal cord Syrinx in cervical cord During the fourth week after fertilization, in which the anterior neuropore closes, there is rapid growth of neural tissue in the cranial region. A second bend in the neural tube at the level of the mesencephalon is the mesencephalic (or cephalic) flexure. The pontine flexure divides the hindbrain into the myelencephalon caudally and the metencephalon rostrally.

Diseases

- Warman Mulliken Hayward syndrome

- Acrofacial dysostosis Catania form

- Iophobia

- Chylous ascites

- Cartilage hair hypoplasia

- Rh disease

- Miller Fisher syndrome

- Liver neoplasms

- Charcot Marie Tooth disease, neuronal, type D

- Hemophilia A

Order silagra 100mg on line

Its roots exit into the interpeduncular fossa (and cistern) via a delicate groove on the lateral wall of this midline space young healthy erectile dysfunction generic silagra 100mg line, the oculomotor sulcus. This innervation involves ipsilateral muscles except for the superior rectus motor neurons, whose axons decussate within the nucleus to enter the contralateral oculomotor nerve. Although seemingly significant, this crossed pathway is typically ignored in the clinical setting because the effect of losing the innervation to the (contralateral) superior rectus muscle is usually masked by the actions of the functionally intact muscles in that orbit. Emerging from the midbrain, the nerve passes between the posterior cerebral and superior cerebellar arteries, enters the interpeduncular cistern, and then penetrates the dura lateral to the sella turcica to course within the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus (see Chapter 8). In the orbit, the oculomotor nerve divides into superior and inferior divisions, each division forming a few small communicating branches to the ciliary ganglion in addition to their muscle branches. There are four smooth muscles related to each orbit that require visceromotor innervation. In contrast, the dilator pupillae muscle and the superior tarsal muscle are activated by sympathetic innervation. Postganglionic sympathetic fibers exit the superior cervical ganglion and course, via the internal carotid plexus, to join the ophthalmic artery. Coursing into the orbit with the latter artery via the optic canal, sympathetic postganglionic fibers may join the ciliary ganglion directly, may join the nasociliary nerve (a branch of V2 from which the long ciliary branches originate), or may join the oculomotor nerve and then enter the ciliary ganglion. Once in the ciliary ganglion, the sympathetic fibers continue, without synapsing, into the short ciliary nerves to reach the dilator pupillae muscle. Note the apposition of this nerve root to the superior cerebellar artery and the posterior cerebral artery. The oculomotor nerve passes through the superior orbital fissure along with the abducens and trochlear roots. Although it is known that the extraocular muscles contain muscle spindles, the oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens nerves are regarded as purely motor nerves. The spindle afferent fibers appear to join sensory nerves in the orbit, such as the frontal and nasociliary nerves, and eventually pass through V1 to reach their cell bodies in the trigeminal ganglion. From here, sensory information enters the brainstem via the sensory root of the trigeminal nerve. The oculomotor nucleus does not receive direct cortical projections via the corticonuclear system. Consequently, cortical and capsular lesions have an effect on the actions of muscles innervated by the oculomotor nerve, but this effect is indirect and results from the loss of cortical input to the brainstem gaze control centers. Lesions involving the oculomotor nucleus, the oculomotor nerve in the interpeduncular cistern, or the nerve in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus all generally have the same result. As a result, the ipsilateral eye assumes an abducted and depressed position (down and out) owing to the unopposed action of the lateral rectus and superior oblique muscles. The patient also experiences diplopia (double vision) because the image seen by each eye cannot be directed to corresponding portions of each retina because most of the extraocular muscles in one eye are not functional. Furthermore, interruption of the preganglionic parasympathetic fibers in the oculomotor nerve results in characteristic signs and symptoms in the ipsilateral eye. First, the pupil is dilated (mydriasis) and nonreactive to light because the sphincter pupillae muscle is denervated (the dilator pupillae muscle, innervated by sympathetic fibers, is intact). Second, the lens in the ipsilateral eye cannot accommodate because the ciliary muscle is also denervated. Third, although the innervation to the superior tarsal muscle is intact because the course of the sympathetic fibers does not involve the oculomotor nerve outside the orbit, the upper eyelid exhibits ptosis (droop) because the levator palpebrae has been denervated by the oculomotor nerve lesion. Because the parasympathetic fibers are located near the periphery (outer surface) of the oculomotor nerve, visceromotor signs and symptoms, such as a subtle ptosis or mildly diminished pupil reactivity, can appear before the onset of, or in the absence of, any extraocular muscle dysfunction with external compressive injury to the oculomotor nerve. The external compression affects the superficially located, smaller-diameter visceromotor fibers first. In contrast, in diabetic patients, the onset of an eye movement disorder may not be accompanied by visceromotor signs or symptoms. Isolated lesions of the oculomotor nerve distal to its passage through the superior orbital fissure are relatively rare and produce variable symptoms, depending on the location of the lesion. Neuroanatomy in Clinical Context: An Atlas of Structures, Sections, Systems, and Syndromes. Cranial Neuroimaging and Clinical Neuroanatomy: Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Computed Tomography. Haines Overview-212 Development of the Diencephalon-212 Basic Organization-214 Dorsal Thalamus (Thalamus)-215 Anterior Thalamic Nuclei-215 Medial Thalamic Nuclei-215 Lateral Thalamic Nuclei-216 Intralaminar Nuclei-219 Midline Nuclei-219 Thalamic Reticular Nucleus-219 Summary of Thalamic Organization-219 Internal Capsule-220 Hypothalamus-220 Lateral Hypothalamic Zone-220 Medial Hypothalamic Zone-221 Afferent Fiber Systems-222 Efferent Fibers-222 Ventral Thalamus (Subthalamus)-222 Epithalamus-222 Vasculature of the Diencephalon-223 involved in the control of visceromotor (autonomic) functions. In this respect, the hypothalamus regulates functions that are "automatically" adjusted (such as blood pressure and body temperature) without our being aware of the change. In contrast, conscious sensation and some aspects of motor control are mediated by the dorsal thalamus. The ventral thalamus and epithalamus are the smallest subdivisions of the diencephalon. The ventral thalamus includes the subthalamic nucleus, which is linked to the basal nuclei of the forebrain and functions in the motor sphere; lesions in the subthalamus give rise to characteristic involuntary movement disorders. The cell groups that give rise to the diencephalon form in the caudomedial portion of the prosencephalon, bordering on the space that will become the third ventricle. The developing brain at this level consists initially of a roof plate and the two alar plates; it lacks a well-defined floor plate and basal plates. This groove, the hypothalamic sulcus, divides the alar plate into a superior (dorsal) area, the future dorsal thalamus, and an inferior (ventral) portion, the future hypothalamus. This choroid plexus is continuous through the interventricular foramina with that of the lateral ventricles. Elsewhere, in locations around the perimeter of the third ventricle, specialized patches of ependyma lie on the midline and form unpaired structures called the circumventricular organs. These cellular regions are characterized by the presence of fenestrated capillaries, which implies an absence of the blood-brain barrier. The diencephalon includes the dorsal thalamus, hypothalamus, ventral thalamus, and epithalamus, and it is situated between the telencephalon and the brainstem. In general, the diencephalon is the main processing center for information destined to reach the cerebral cortex from all ascending sensory pathways (except those related to olfaction). The right and left halves of the diencephalon, for the most part, contain symmetrically distributed cell groups separated by the space of the third ventricle. Some of the thalamic nuclei receive somatosensory, visual, or auditory input and transmit this information to the appropriate area of the cerebral cortex. Other thalamic nuclei receive input from subcortical motor areas and project to those parts of the overlying cortex that influence the successful execution of a motor act. A few thalamic nuclei receive a more diffuse input and accordingly relate in a more diffuse way to widespread areas of the cortex. The hypothalamus is also composed of multiple nuclear subdivisions and is connected primarily to portions of the forebrain, brainstem, and spinal cord. This part of the diencephalon is 212 the Diencephalon 213 are thought to release metabolites and neuropeptides into the cerebrospinal fluid or into the cerebrovascular system. A downward extension of the floor of the third ventricle, the infundibulum, meets the Rathke pouch, an upward outpocketing of the stomodeum, the primitive oral cavity. By the end of the second month, the Rathke pouch loses its connection with the developing oral cavity but maintains its attachment to the infundibulum. Lateral (A) and midsagittal (B) views of the forebrain at about 8 to 9 weeks of gestational age. The cross-sectional views (C, D) are taken from the planes shown in B and emphasize diencephalic structures. The interventricular foramen is the space (containing a small portion of choroid plexus) located between the column of the fornix and the anterior tubercle of the thalamus. These tumors mimic lesions of the pituitary gland and may cause visual problems, diabetes insipidus, and increased intracranial pressure. The dorsal thalamus is located superior to the hypothalamic sulcus and extends from the interventricular foramen caudally to the level of the splenium of the corpus callosum. The hypothalamus lies inferior to the hypothalamic sulcus and is bordered rostrally by the lamina terminalis and caudally by a line that extends from the posterior aspect of the mammillary body superiorly to intersect with the hypothalamic sulcus. Epithalamic structures are located posteriorly and caudally, in close apposition to the posterior commissure, and include the pineal gland, the habenular nuclei, and the main afferent bundle of these nuclei, the stria medullaris thalami. The last cell group is located in the portion of the internal medullary lamina that separates the lateral and medial nuclear groups. In addition, there are midline thalamic nuclei located just superior to the hypothalamic sulcus. Although considered here as components of the lateral nuclear group, the geniculate nuclei are sometimes considered as a separate part of the thalamus, the metathalamus. It receives a variety of ascending inputs and projects, via thalamocortical fibers to various cortical areas or gyri, and receives reciprocal connections, via corticothalamic fibers, from those cortical targets to which it sends projections.

Order silagra 50 mg mastercard

If a hypothetical neuron were spherical (for simplicity) and 20 m in diameter erectile dysfunction family doctor generic 50 mg silagra, it would have a surface area of almost 1300 m2, a capacitance of 11 pF per cell, and thus a charge of 1 pC (picocoulomb) when the membrane voltage is 90 mV. Although this may seem to be a lot, the cell volume of this neuron would be 4 pL (picoliters) and contain 250 billion potassium ions and 25 billion chloride ions. Together, these two ions alone are 40,000 times the number required to charge the membrane. Pain and a Syndrome of Periodic Paralysis Pathologic conditions may alter the concentration of ions ordinarily seen in nerve cells (Table 3. For instance, tissue injury causes a local increase in the potassium concentration as these cells release their contents. Thus one source of pain is simply the direct stimulation of nerve endings by elevated potassium concentration in the tissue interstitium. Because the conductance paths are in parallel, the driving forces of the ions combine in proportion to their relative permeabilities to generate a voltage across the membrane capacitance. In rare individuals who have certain genetic abnormalities, extracellular concentration of potassium can fall dramatically when epinephrine or insulin stimulates its uptake by muscle cells, leading to muscle weakness and even paralysis. Surprisingly, the muscle membrane potentials are less negative than normal, just the opposite of what the Nernst equation predicts. This membrane potential change is slow, allowing the muscle fiber to undergo accommodation and so become inexcitable. Two distinct families of pore-forming proteins kill bacteria and those cells that harbor viruses. As a consequence, the formation of just a single C9 aggregate or insertion of a single perforin molecule results in a large flow of ions. If Vm = -90 mV (to take a simple example), the driving force on the sodium will be (- 90 mV) - (+ 70 mV) = - 160 mV Because one ampere is the flow of 6. By following the movements of the various ions due to the electrical forces on them, it is possible to see that the cell gains osmotic particles and so swells. For instance, because the net driving force on sodium is negative, it will enter the cell, with its positive charge tending to cancel the negativity of the membrane potential. Thus, when sodium and chloride enter the cell, water follows, and the cell swells. Thus attack by complement or killer T cells leads inexorably to cell swelling and lysis both because important metabolic contents are lost and because the osmotic pressures exerted by the remaining cell proteins cause cell swelling and death. Microbial Attacks: Antibiotics Insertion of ion channels into cell membranes is also a weapon deployed by many microorganisms. Antibiotics such as amphotericin and gramicidin, and -staphylotoxins from Staphylococcus aureus, lyse cells by broaching their membranes with large pores. When it is used clinically, amphotericin preferentially attacks fungal cells in fungal meningitis, but there is a narrow therapeutic range because amphotericin also attacks cell membranes in the nervous system. In overwhelming sepsis, -staphylotoxins attack the Electrochemical Basis of Nerve Function 41 Table 3. Similarly, nervous input is electrically integrated by the combined actions of excitatory and inhibitory synapses on nerve cell bodies. The remainder of this chapter explains how the principles governing chemical and electrical forces contribute to the function of the nervous system. These graded responses are generator potentials that can be the direct result of the stimulus opening or closing membrane channels or increasing the current through existing membrane channels. More often, intermediary chemical signals connect the initial sensation to the opening of membrane channels, processes that are discussed further in Chapter 4. Mechanotransduction-the sensing of touch, of hearing, of cell volume change-is the direct result of stretch-activated channels opening as the cell membrane is deformed. Mechanosensitive channels have diverse structures, proving that there is no single way to detect strain on the cell membrane. Piezo channels are large trimers, having 14 transmembrane segments per monomer, distinctive paddles on the outside face, and anchor points and smaller beams on the inside. The pore opens when the membrane pulls on the closed conformation (blue-gray), lowering the paddles and torqueing the beams flat (yellow-brown). Functionally, these channels, along with assorted accessory proteins, are used for distinct purposes. For instance, one use of Piezo2 is to sense prolonged or transient vibrations in Merkel cells or their A sensory nerve fibers. Pathologically, mutations of mechanoreceptors underlie certain congenital syndromes of extreme contractures that are present at birth; two Piezo2 variants that have an increased probability for the channel to be in the open state underlie distal arthrogyrposis type 5. Ligands that bind to receptors may either activate them (agonists) or keep them from functioning (antagonists). Our body uses many different transmitters acting on many, many distinctly different receptors to confer specificity of action throughout the nervous system. As with the generator potentials, neurotransmitters act to open membrane channels either directly or via intermediary signals. Direct activation of synaptic channels occurs in the cys-loop and glutamatergic receptor families as well as in one purinergic receptor type (Table 3. All synaptic receptor molecules have a distinct region that specifically binds the transmitter. In the presence of the transmitter, three loops of the subunit come together with a loop of the or subunit to form a box of nonpolar and aromatic amino acids, primarily tryptophans and tyrosines. A plant product, curare was the first nondepolarizing muscle relaxant used clinically. The specificity, duration of action, and potency of effect are largely due to the extremely high affinity of the drug to the binding site, which in turn reflects how well the drug fits into the box-like geometry of the amino acids that comprise the 1 and the 1 interfaces. Because of this distinction, hexamethonium was used to block the sympathetic nervous system at the ganglionic level as an antihypertensive. The other cys-loop receptors also have characteristic activators and inhibitors that are analogous to those active at the nicotinic receptor. The membrane domain is composed of 20 helices (4 per subunit), 5 of which (1 per subunit) are mobile and form the ion pore. The remaining helices are hydrophobic and form a rigid pentagonal frame embedded in the membrane. The Electrochemical Basis of Nerve Function 43 inhibitory activity and leading to a hyperexcitable state, a tool used long ago by medical students to remain alert for examinations; this was effective but only within a very narrow range of dosing because slightly higher doses cause convulsions. Thus specificity of action within the nervous system is conferred by the different structures of the various receptor molecules in their transmitter-recognition region. Excitatory and Inhibitory Synaptic Currents the specific recognition of a transmitter molecule is only one of the two necessary functions of a receptor molecule; the second is to effect a change in the target cell. Depolarizing blockers are partial agonists as well, with a real but limited ability to effectively trigger action potentials (hence depolarizing), leading to unwanted muscle contractions during induction of anesthesia, a cause of muscle soreness the next day. The cleft transmitter (A) concentration rises within a millisecond as it diffuses from its release site and then declines with time as it is hydrolyzed by cleft acetylcholinesterase. The postsynaptic current (G) is the sum of activities of many single channels (B through F), which together cause a depolarization in the surrounding muscle membrane (H). In this case, afferent nerve fibers from the carotid body baroreceptors are seen to fire rhythmically in response to the increase in arterial blood pressure during systole. These fibers have a low degree of tonic activity plus a superimposed phasic discharge proportional to the rate of change in blood pressure. As the sodium ions first enter the nerve cell and then potassium ions leave, electrical charges are removed and then added to the extracellular fluid. The four different groups each have a characteristic set of functions, which is more fully described in Chapter 17. At a low stimulus strength, only the A peak appears, as the largest fibers have the lowest thresholds. For a 30-cm separation between the stimulating and the recording electrodes, the delay should be 4 ms because the expected conduction velocity is expected to be 80 m/s or more. In a diabetic or a compression neuropathy, the speed would decline or conduction would fail altogether. An extracellular recording of a small bundle of baroreceptor afferents (A) measures the electrical currents of action potentials that fire in response to changes in blood pressure, plotted in the lower trace. An intracellular recording from a myelinated nerve axon measures the voltages associated with an action potential (B): a 50-s electrical stimulus at time zero, the rapid upstroke to a peak voltage greater than 0 mV, and a complete recovery by 1 ms.

Discount silagra 100mg with visa