Discount azithromycin 250 mg visa

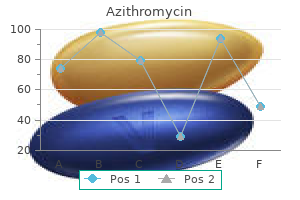

These responses antibiotics for uti chlamydia order 500 mg azithromycin overnight delivery, produced by rapidly reversing the pat tern of black and white squares, are easier to detect and to measure than are flash responses and are more consistent in waveform from one individual to another. The pattern shift stimulus applied first to one eye and then to the other, can demonstrate conduction delays in the visual pathways of patients who have had disease of the optic nerve-even when there are no residual signs of reduced visual acuity, visual field abnormalities, alterations of the optic nerve head, or changes in pupillary reflexes. Furthermore, the presence of a normal visual evoked response belies blindness from a lesion in the anterior visual pathways and their projections to the occipital cor tex. Glaucoma and other dis eases involving structures anterior to the retinal ganglion cells, if severe enough to affect the optic nerve, may also produce increased latencies. The use of these tests in detecting psychogenic blindness has already been mentioned. By presenting the pattern-shift stimulus to one hemifield, it is possible to isolate a lesion to an optic tract or radiation, or one occipital lobe, but with much less precision than that provided by the usual monocular testing. Between 1,000 and 2,000 clicks, delivered first to one ear and then to the other, are recorded through scalp elec trodes and superimposed on each other by computer and thereby maximized. The presence of wave I and its absolute latency test the integrity of the auditory nerve. The most important are the interwave latencies between I and ill, and ill and V (see Table 2-4). A lesion that affects one of the auditory nuclear relay stations or its immediate connections manifests itself by a delay in the appearance or an absence of all subsequent waves; in other words, the nuclei behave as if they are connected in series. These effects are more pronounced on the side of the stimulated ear than contralaterally. This is difficult to understand, as a majority of the cochlear-superior olivary-lateral lemniscal-medial geniculate fibers cross to the opposite side. It is also surprising that a lesion of one relay station would allow impulses, even though delayed, to continue their ascent and be recordable in the cerebral cortex. Bilateral prolongation of latencies, demonstrated by separate stimulation of each eye, can be caused by lesions in both optic nerves, the optic chiasm, or the visual pathways posterior to the chiasm. A compressive lesion of an optic nerve will have the same effect as a primarily demyelinating one. Diagram of the proposed electrophysiologic-anatomic correlations in human subjects. The impulses generated in large touch fibers by 500 or more stimuli and averaged by computer can be traced through the corresponding peripheral nerves, spinal roots, and posterior columns to the cune ate and gracile nuclei in the lower medulla, through the medial lemniscus to the contralateral thalamus, and thence to the sensory cortex of the parietal lobe. The normal waveforms are designated by the symbols P (positive) and N (negative), with a number indicating the interval of time in milli seconds from stimulus to recording. As shorthand for the polarity and approximate latency, the summated wave that is recorded at the cer vicomedullary junction is termed N/P13, and the corti cal potential from median nerve stimulation seen in two contiguous waves of opposite polarity is called N19-P22. The set of responses shown at left is from a normal subject; the set at right is from a patient with multiple sclerosis who had no sensory symptoms or signs. Each trace is the averaged response to 1,024 stimuli; the superimposed trace represents a repetition to demonstrate waveform consistency. Recordings with pathologically verified lesions at these levels are to be found in the monograph by Chiappa. This test has been most helpful in establishing the existence of lesions in spinal roots, posterior columns, and brainstem in disorders such as the ruptured lumbar and cervical discs, multiple scle rosis, and lumbar and cervical spondylosis when the clinical data are uncertain. The cerebral counterpart also pertains-namely, that obliteration of the cortical waves (assuming that all preceding waves are unaltered) reflects profound damage to the somatosensory pathways in the hemisphere or to the cortex itself. For example, the bilat eral absence of cortical somatosensory waves after cardiac arrest is a powerful predictor of a poor clinical outcome; the persistent absence of a cortical potential on one side after stroke usually indicates such profound damage that only a limited clinical recovery is to be expected. This technique, introduced by Marsden and associates, painlessly stimulates only the largest motor neurons (presumably Betz cells) and the fastest-conducting axons. The difference in time between the motor cortical and cervical activa tion of hand or forearm muscles reflects the conduction velocity of the cortical-cervical cord motor neurons. The technique has been used to understand the organization, function, and recovery of the motor cortex and the patho physiology of stroke, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Endogenous Event-Related Evoked Potentials Among the very late brain electrical potentials (> 100-ms latency) that can be extracted from background activity by computer methods, are a group that cannot be clas sified as sensory or motor but rather as psychophysical responses to environmental stimuli. These responses are of very low voltage, often fleeting and inconsistent, and of unknown anatomic origin. The most studied types occur approximately 300 ms (P300) after an attentive subject identifies an unexpected or novel stimulus that has been inserted into a regular train of stimuli. Almost any stimulus modality can be used and the potential occurs even when a stimulus has been omitted from a regular pattern. The amplitude of the response depends on the difficulty of the task and has an inverse relation ship to the frequency of the unexpected or "odd" event; the latency depends on the task difficulty and other fea tures of testing. There is therefore no single P300; instead, there are numerous types, depending on the experi mental paradigm. Prolongation of the latency is found with aging and in dementia as well as with degenerative diseases such as Parkinson disease, progressive supra nuclear palsy, and Huntington chorea. The P300 remains a curiosity for the clinical neurologist because abnormalities are detected only when large groups are compared to normal indi viduals, and the technique is not as standardized as the conventional evoked potentials. A review of the subject can be found in sections by Altenmiiller and Gerloff and by Polich in the Niedermeyer and Lopes DaSilva text on electroencephalography. A description of these methods and their clinical uses is found in the chapters dealing with cerebral function (Chap. The study of mitochondrial genetics has allowed the detection of an entire category of diseases that affect this subcellular structure, as detailed in Chap. Brain biopsy, aside from its main use in the direct sampling of a suspected neoplasm, may be diagnostic in cases of granulomatous angiitis, some forms of encepha litis, infectious abscesses. Biopsy of the pachymeninges or leptomeninges may disclose vasculitis, sarcoidosis, other granulomatous infiltrations, or an obscure infec tion, but its sensitivity is low. Biopsy is now generally avoided in cases of suspected prion disease because of the risk of transmitting the causative agent. In choosing to perform a biopsy in any of these clinical situations, the paramount issue is the likelihood of establishing a definitive diagnosis-one that would permit successful treatment or otherwise enhance the management of the disease. American Electroencephalographic Society: Guidelines in elec troencephalography, evoked potentials, and polysomnography. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 5th ed. Polich J: P300 in clinical applications, in Niedermeyer E, Lopes DaSilva F (eds): Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 4th ed. Strupp M, Schueler 0, Straube A, et aJ: "Atrauma tic" Sprotte needle reduces the incidence of post-lumbar puncture headache. The large motor neurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord and the motor nuclei of the brainstem. The motor neurons in the frontal cortex ad jacent to the rolandic fissure transmitted to muscle. Because the m otor fi bers that extend fro m the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord are not confi ned to the pyram idal 3. Several brainstem nuclei that project to the spinal cord, notably the pontine and medul the upper motor neurons, to d isti ng u ish them from the lower motor neurons. Defin itions Paralysis means loss of voluntary movement as a result of interruption of one of the motor pathways at any point from the cerebrum to the muscle fiber. The word plegia comes from a Greek word meaning "to strike," and the word palsy is from an old French word that has the same mean ing as paralysis. One generally uses paralysis or plegia for severe or complete loss of motor function and paresis for partial loss. All variations in the force, range, rate, and type of move ment are determined by the number and size of motor units called into action and the frequency and sequence of firing of each motor unit. Weak movements involve relatively few small motor units; powerful movements recruit many more units that accumulate to an increasing size. Within a few days after interruption of a motor nerve, the individual denervated muscle fibers begin to contract spontaneously. Inability of the isolated fiber to maintain a stable membrane potential is the likely explanation.

Diseases

- Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome GCPS

- Fatal familial insomnia

- Graham Boyle Troxell syndrome

- Eosinophilic granuloma

- Thrush

- Hydatidiform mole

- Protein S acquired deficiency

- Ceroid lipofuscinois, neuronal 2, late infantile

- Nakamura Osame syndrome

Buy azithromycin 100mg with amex

A removal of the modulating influence of the cerebellum on the a mechanism antimicrobial gorilla glass purchase azithromycin online pills, but it is uncertain whether the disinhib ited motor activity is then expressed through corticospinal or reticulospinal pathways. For example, pentylenetetra zol (Metrazol) injections evoke myoclonus in the limbs of animals, and the myoclonus persists after transection of corticospinal and other descending tracts until the lower brainstem (medullary reticular) structures are destroyed. The subject has been reviewed by Wilkins and colleagues and by Ryan and associates. As pointed out by Suhren and associates and by Kurczynski, the condition is transmitted in some families as an autosomal dominant trait. In the proband described by Kurczynski, affected infants were persistently hyper tonic and hyperreflexic (up to 2 to 4 years of age) and had nocturnal and sometimes diurnal generalized myoclonic jerks, all of which subsided with maturation. Later in life, excessive startle must be distinguished from epileptic seizures, which may begin with a startle or massive myoclonic jerk (startle epilepsy) and from the multiple tic disorder, Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, of which startle may be a prominent manifestation (Chap. With idiopathic startle disease, even with a fall, there is no loss of consciousness, and the manifestations of tic and other neurologic abnormalities are absent. Others, on the basis of testing by somatosen sory evoked potentials, have suggested that hyperactive long-loop reflexes constitute the physiologic basis of startle disease (Markand et al). Wilkins and coworkers consider hyperexplexia to be an independent phenomenon (dif ferent from the normal startle reflex) and to fall within the spectrum of stimulus-sensitive myoclonic disorders. Presumably, the altered glycine receptor in startle disease is the source of some form of hyperexcitability in one or another of the motor or reticular alerting systems. The nature of the phenomenon displayed by the "jumping Frenchmen of Maine" has been disputed. The syndrome was described originally by James Beard, in 1868 among small pockets of French-speaking lumber j acks in northern Maine. The subjects displayed a greatly exaggerated response to minimal stimuli, to which there was no adaptation. The reaction consisted of jumping, raising the arms, screaming, and flailing of limbs, some times with echolalia, echopraxia, and a forced obedience to commands, even if this entailed a risk of serious injury. A similar syndrome in Malaysia and Indonesia is known as latah and in Siberia as myriachit. This syndrome has been framed in psychologic terms as conditioned responses (Saint-Hilaire et al) or as culturally deter mined behavior (Simons). This normal startle reflex is probably a protective reaction, being seen also in animals, and its purpose seemingly is to prepare the organism for escape. By pathologic startle we refer to a greatly exaggerated startle reflex and to a group of other stimulus-induced disorders of which startle is a predominant part. In most ways, startle cannot be sepa rated from myoclonus (simplex) except for its generalized nature and a striking evocation by various stimuli. Any stimulus-most often an auditory one but also a flash of light, a tap on the neck, back, or nose, or even the pres ence of someone behind the patient-can normally evince a sudden contraction of the orbicularis, neck, and spinal musculature and even the legs. However, in the abnor mal startle response that occurs in the diseases discussed below, the contraction is of greater amplitude and is more widespread, with less tendency to habituate. Aside from exaggerated forms of the normal startle reflex, the commonest isolated syndrome is so-called startle disease, also referred to as hyperexplexia or hyperekplexia (see Gastaut and Villeneuve). Also, the act of flexing the neck and bring ing the arms close to the torso may reduce the intensity of an attack (Vigevano maneuver). When limited to the neck muscles, the most common type of focal dystonia, the spasms may be more pronounced on one side, with rota tion and partial extension of the head (idiopathic cervical dystonia, or torticollis), or the posterior or anterior neck muscles may be involved predominantly and the head becomes hyperextended (retrocollic spasm, or retrocollis) or inclined forward (procollic spasm, or anterocollis). Other dystonias restricted to craniocervical muscle groups are spasms of the orbicularis oculi, causing forced closure of the eyelids (blepharospasm) and contraction of the muscles of the mouth and jaw, which may cause forceful opening or closure of the jaw and retraction or pursing of the lips (oromandibular dystonia). With the latter condition, the tongue may undergo forceful involuntary protrusion; the throat and neck muscles may be thrown into violent spasm when the patient attempts to speak or the facial muscles may contract in a grimace; the laryn geal muscles may be involved, imparting a high-pitched, strained quality to the voice (spasmodic dysphonia). More often, spasmodic dysphonia (sometimes incor rectly termed "spastic" dysphonia) occurs as an isolated phenomenon (Chap. These movement disorders are involuntary and can not be inhibited, thereby differing from habit spasms or tics. At one time, torticollis was thought to be a type of psychological disorder but all now agree that it is a localized form of dystonia. The tremor in particular may cause difficulty in diagnosis if the slight degree of underlying dystonia is not appreciated by careful observation and by palpation of the involved muscles. Any of the typical forms of restricted dystonia may represent a tardive dyskinesia; i. Also, restricted dystonias of the hand or foot often emerge as components of a number of degenerative diseases Parkinson disease, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy (all described in Chap. These dystonias may also occur in meta bolic diseases such as Wilson disease and nonwilsonian hepatolenticular degeneration. Rarely, a focal dystonia emerges transiently after a stroke that involves the stria topallidal system, mainly the internal segment of the pallidum or the thalamus, but the varied locations of these infarctions makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the mechanism of dystonia. Several such cases that fall into the category of symptomatic or secondary dys tonias are described by Krystkowiak and colleagues and by Munchau and colleagues. The pathogenesis of the idiopathic focal dystonias is uncertain, although there is evidence that some of them, like the generalized dystonias, are genetically determined. Authoritative commentators, including Marsden, classed the apparently idiopathic adult-onset focal dystonias with the category of genetically determined generalized torsion dystonia. This view is based on several lines of evidence: the recognition that each of the focal dystonias may appear as an early component of generalized syndrome in chil dren, the occurrence of focal and segmental dystonias in family members of these children, as well as a tendency of the dystonia in some adult patients to spread to other body parts. The genetics of primary torsion dystonia is more complex than portrayed here, and is reviewed in Chap. It is noteworthy that no consistent pathologic changes have been demonstrated in any of the idiopathic or genetically determined dystonias. Most physiologists cast the disorder in terms of reduced cortical inhibition of unwanted muscle contractions, as summarized by Berardelli and colleagues. Specific physiologic changes in the cortical areas that are pertinent to the dystonias asso ciated with overuse of certain body parts (occupational dystonias) are described below. The quality of the neck and head movements varies; they may be deliberate and smooth or jerky but most often cause a persistent deviation of the head to one side. Sometimes brief bursts of myoclonic twitching or a slightly irregular, high-frequency tremor accompanies deviation of the head, possibly representing an effort to overcome the contraction of the neck muscles; however, the tremor tends to beat in the direction of the dystonic movement. At times the tremor is far more dominant than is the dystonia, causing difficulty in diagnosis. The spasms are often worse when the patient stands or walks and are characteristically reduced or abolished by a contactual stimulus, such as placing a hand on the chin or neck or exerting mild but steady counterpressure on the side of the deviation or sometimes on the opposite side, or bringing the occiput in contact with the back of a high chair. In chronic cases, as the dystonic position typically becomes increasingly fixed in position, the affected muscles undergo hypertrophy. Pain in the contracting muscles is a common complaint, especially if there is associated cervical arthropathy. The most prominently affected muscles are the ster nocleidomastoid, levator scapulae, and trapezius. The levator spasm lifts the affected shoulder slightly, and tautness in this muscle is sometimes the earliest feature. As a general observation, we have been impressed with information gained from palpating the muscles of the neck and shoulder in order to establish which muscles are the predominant causes of the spasm and to direct treatment to them as noted further on. In most patients the spasms remain confined to the neck muscles and per sist in unmodified form, but in some the spasms spread, involving muscles of the shoulder girdle and back or the face and limbs. About 15 percent of patients with tor ticollis also have oral, mandibular, or hand dystonia, 10 percent have blepharospasm, and a similarly small num ber have a family history of dystonia or tremor (Chan et al). As already noted, no neuropathologic changes have been found in the single case studies reported by Tarlov and by Zweig and colleagues. Spasmodic torticollis is resistant to treatment with L-dopa and other antiparkinsonian agents, although occasionally they give slight relief. They are, however, effective in those few instances in which dystonia is a prelude to Parkinson disease. In a few of our patients (four or five of several dozens), the condition disap peared without therapy, an occurrence observed in 1 0 to 20 percent in the series of Dauer et al. In their experience, remissions usually occurred during the first few years after onset in patients whose disease began relatively early in life; however, nearly all these patients relapsed within 5 years. Tre atm e nt the periodic (every 3 to 6 months) injection of small amounts of botulinum toxin directly into several sites in the affected muscles is by far the most effective form of treatment. All but 10 percent of patients with torticollis have had some degree of relief from symptoms with this treatment. Adverse effects (excessive weakness of injected muscles, local pain, and dysphagia-the latter from a systemic effect of the toxin) are usually mild and transitory. Five to 10 percent of patients eventually become resistant to repeated injec tions because of the development of neutralizing antibodies to the toxin (Dauer et al).

Buy azithromycin 100mg

The image is essen tially a map of the hydrogen content of tissue antibiotics for strep uti cheap azithromycin 250mg online, therefore reflecting largely the water concentration, but influenced also by the physical and chemical environment of the hydrogen atoms. The terms Tl- and T2-weighting refer to the time constants for proton relaxation; these may be altered to highlight certain features of tissue structure. Lesions within the white matter, such as the demyelination of multiple sclerosis, are more easily seen on T2-weighted images, appearing hyperintense against normal white matter (Table 2-3). These sequences can reveal lobar microhemorrhages as seen in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Abnormalities such as syringomyelia, herni ated discs, tumors, epidural or subdural hemorrhages, areas of demyelination, and abscesses are well delineated. Additional radiofrequency pulses can be applied to Tl- and T2-weighted images in order to selectively sup press signal from fluid or fat. The vertebral bodies are separated by intervertebral ctiscs and the spinous processes are seen posteriorly. The conus meduUaris terminates at the L2 vertebral level (A-B) and the nerve roots of the cauda equina are clearly seen within the posterior thecal sac (A-C). The nerve roots of the cauda equina are seen within the posterior thecal sac (A-C). In C and F, traversing nerve roots within the lateral recess of the spinal canal are seen. Some form of sedation is required in these individuals and most hospitals have services to safely accomplish conscious sedation for this purpose. Studying a patient who requires a ventilator is also dif ficult but manageable by using either manual ventilation or nonferromagnetic ventilators (Barnett et al). For this reason it is wise, in appropriate patients, to obtain plain radiographs of the orbits so as to detect metal in these regions. However, many new implant able medical devices have been developed that do not distort the magnetic field. Most of the newer, weakly ferromagnetic prosthetic heart valves, joint prostheses, intravascular access ports, aneurysm clips, and ven tricular shunts and adjustable valves do not represent an untoward risk for magnetic imaging although shunt valves may require resetting. However, current data indicate that imaging may be performed provided that the study is medically indicated. In recent years, an additional risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, a severe cutaneous sclerosing disease, has been linked to the administration of gadolinium. The problem had not been appreciated previously in part because of its rarity (the frequency has not been well established) and because of a delay in the appearance of sclerosis in the kidney, of several days to two months. Fat-suppression, which can be applied to T1 or T2 sequences, can be used to dem onstrate inflamm ation of the optic nerve, visualize patho logic inflammation within the vertebral bodies, and show thrombus within the false lumen of a cervical dissection. Preferential movement of water molecules along a particular direction, for example, parallel to white matter tracts, is referred to as anisotropy. This phenom enon is seen when the free movement of water within a tissue becomes more isotropic, as with vasogenic edema. The caudate nuclei, pu tamen, and thalamus appear brigh ter than the internal capsule. Note that white matter appears brighter than gray matter and the corpus callosum is well defined. The pons, medulla, and cervicomedullary j unction are well delineated, and the pi tuitary gland is demonstrated with a normal posterior pituitary bright spot. However, a surprising number of incidental brain lesions of consequence are also exposed. For example, a large survey of asymptomatic adults who were being followed in the "Rotterdam Study" is in accord with several prior studies in which cerebral aneurysms were found in approximately 2 percent, meningiomas in 1 percent, and a smaller but not insignificant number of vestibular schwannomas and pituitary tumors; the menin giomas, but not the aneurysms, increased in frequency with age. One percent had the Chiari type I malformation, and a similar number had arachnoid cysts. In addition, seven percent of adults older than age 45 years had occult strokes, mostly lacunar. Because this survey was performed with out gadolinium infusion, it might be expected that even more small lesions could be revealed (Vemooij et al). This modality detects damage to , or displace ment of white matter tracts because of trauma, vascular injury, or tumor, in extraordinary detail. Tractography is also occasionally used in surgical planning to localize critical white matter tracts avoid their inadvertent tran section during operations. This technique has also been used in pre-surgical planning in order to avoid damage to eloquent cortex, and in epilepsy to help localize seizure foci. The technique has been applied to specially labeled ligands of beta-amyloid, producing images of the deposition of this protein in Alzheimer disease. No doubt this approach will become increasingly important in the study of degenerative diseases and their response to treatment. The ability of the technique to quantitate neurotransmitters and their receptors also promises to be of importance in the study of Parkinson disease and other degenerative conditions. However, this technology is costly and does not always add to the certainty of diagnosis. Radioligands (usually containing iodine) are incor porated into biologically active compounds, which, as they decay, emit only a single photon. This procedure allows the study of regional cerebral blood flow under conditions of cerebral ischemia and regional degen erative diseases of the cortex or during increased tissue metabolism. A time-intensity curve is produced, from which measurements of cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, and transit time can be derived. Perfusion imaging has provided a means of detecting regions of ischemic tissue, and to monitor the elevated blood volume in certain brain tumors. Choline (Cho), a marker of membrane turnover, is elevated in some rapidly dividing tumors. Progressive cord ischemia from an ill-defined vascular process ensues over the following hours. This same complication may occur at other levels of the cord following visceral or spinal angiography. They can reliably detect intracranial vascular lesions and extracranial arterial ste nosis and are supplanting conventional angiography. Angiogra phy this technique has evolved over the past century to the point where it is a safe and valuable method for the diag nosis of aneurysms, vascular malformations, narrowed or occluded arteries and veins, arterial dissections, and angi itis. However, new endovascular procedures for the ablation of aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, and vascular tumors still may require the incorporation of conventional angiography. Following local anesthesia, a needle is placed in the femoral or brachial artery; a can nula is then threaded through the needle and along the aorta and the arterial branches to be visualized. In this way, a contrast agent is injected to visualize the arch of the aorta, the origins of the carotid and vertebral sys tems, and the extensions of these systems through the neck and into the cranial cavity and the vasculature in and surrounding the spinal cord. Experienced arteriogra phers can visualize the cerebral and spinal cord arteries down to about 0. With cur computer processing it is possible to produce images of the major cervical and intracranial arteries with relatively small amounts of contrast medium introduced through smaller catheters than those used previously. High concentrations of the injected contrast may induce vascu lar spasm and occlusion, and clots may form on the cath eter tip and embolize the artery. This data can be reconstructed into an image that reflects flow related enhancement. The use of these and other methods for the investigation of carotid artery disease is discussed further below and in Chap. U ltrasonography In recent years this technique has been refined to the point where it has become a principal methodology for clinical study of the fetal and neonatal brain and an important ancillary test for evaluating the cerebral vessels in adults. The instrument for this application consists of a trans ducer capable of converting electrical energy to ultra sound waves of a frequency ranging from 5 to 20 kHz. Different tissues have specific acoustic impedances and send echoes back to the transducer, which displays them as waves of variable height or as points of light of varying intensity. In this way, one can obtain images in the neonate of choroid plexuses, ventricles, and central nuclear masses. Intracerebral and subdural hemorrhages, mass lesions, and congenital defects can readily be visualized. Similar instruments are used to insonate the basal vessels of the circle of Willis ("transcranial Doppler"), the cervical carotid and vertebral arteries, and the temporal arteries for the study of cerebrovascular disease. Their greatest use is in detecting and estimating the degree of stenosis of the origin of the internal carotid artery. Occasionally, a cerebral or systemic ischemic lesion is produced, prob ably the result of either particulate atheromatous material dislodged by the catheter, thrombus formation at or near the catheter tip, or less often, by dissection of the artery by the catheter.

Purchase azithromycin discount

In such cases also bacteria during pregnancy azithromycin 250mg on line, a right homonymous hemianopia will be absent, but the alexia may be combined with agraphia and other elements of the Gerstmann syndrome, i. This entire constellation of symptoms is sometimes referred to as the syndrome of the angular gyrus. There is a tendency for patients with anomia to attri bute their failure to forgetfulness or to give some other implausible excuse for the disability, suggesting that they are not completely aware of the nature of their difficulty, but some are aware of the defect. Of course, there are many more patients who fail not only to name objects but also to recognize the correct word when it is given to them. Anomie aphasia has been associated with lesions in different parts of the language area, typically in the left temporal lobe. In these cases, the lesion has been deep to the posterior temporal lobe, particularly in the left thalamus, or in the middle temporal convolution, in a location to interrupt connections between sensory language areas and the hippocampal regions concerned with learning and memory. Occasionally; anomia appears with lesions caused by occlusion of the temporal branches of the posterior cerebral artery; and it is in these instances that we have seen the most pronounced cases of anomia, usually asso ciated with a right hemianopia and alexia but normal writing ability. Anomia may be a prominent manifesta tion of transcortical motor aphasia (see later) and may be associated with the Gerstrnann syndrome, in which case the lesions are found in the frontal lobe and angular gyrus, respectively. An anomie type of aphasia is often an early sign of Alzheimer and Pick disease (minor degrees of it are com mon in old age) and is a principal feature of one type of degenerative lobar cerebral atrophy in the category of the primary progressive aphasias (see Chap. The syndrome is also encountered as a transient phenomenon during recovery from stroke. The relation to disorders of prosody, which is produced by lesions of the nondominant hemisphere, is unclear. LeCours and Lhermitte made an analysis of the disorder based on the obligate use of diphthongs in certain languages; these were not proper! An extensive examination of one case and references to additional ones can be found in the article by Kurowski and colleagues. It might be supposed that all the rules of language derived from the study of aphasia would be applicable to agraphia. One must be able to formulate ideas in words and phrases in order to have something to write as well as to say; hence, disorders of writing, like disorders of speaking, reflect all the basic defects of language. In speech, only one final motor pathway coordinating the movements of lips, tongue, larynx, and respiratory muscles is available, whereas if the right hand is para lyzed, one can still write with the left one, or with a foot, and even with the mouth by holding a pencil between the teeth (a contrivance used by individuals whose arms are paralyzed by cervical root avulsion from motorcycle accidents). Paraphasias appear in the writings of aphasics much the same as they do in speech. The writing of a word can be accomplished either by the direct lexical method of recalling its spelling or by sounding out its phonemes and transforming them into learned graphemes (motor images), i. Some authors state that in agraphia there is a specific difficulty in transforming phonologic information, acquired through the auditory sense, into orthographic forms; others see it as a block between the visual form of phonemes, and the cursive movements of the hand (Basso et al). In support of the latter idea is the fact that reading and writing usually develop together and are long preceded by the development of speech as a means of communication. Pure agraphia as the initial and sole disturbance of language function is a rarity, but such cases have been described as summarized by Rosati and de Bastiani. Pathologically verified cases are virtually nonexistent, but imaging sometimes discloses a lesion of the posterior perisylvian area. This is in keeping with the observation that a lesion in or near the angular gyrus will occasion ally cause a disproportionate disorder of writing as part 39). As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the notion of specific center for writing in the posterior part of the second frontal convolution (the "Exner writing area") has been questioned (see Leischner). However, Croisile and associates do cite cases of dysgraphia in which a lesion (in the case they reported, a hematoma) was located in the centrum semiovale beneath the motor parts of the frontal cortex and direct electrical stimulation of the cortex rostral to the primary motor hand area disturbs handwriting without affecting other language or manual tasks according to Roux and colleagues, a veritable apraxia of writing. Quite apart from these aphasic agraphias, in which spelling and gramm atical errors abound, there are spe cial forms of agraphia caused by abnormalities of spatial perception and praxis. Disturbances in the perception of spatial relationships underlie constructional agraphia. In this circumstance, letters and words are formed clearly enough but are wrongly arranged on the page. Words may be superimposed, reversed, written diagonally or in a haphazard arrangement, or from right to left; in the form associated with right parietal lesions, only the right half of the page is used. Usually one finds other con structional difficulties as well, such as inability to copy geometric figures or to make drawings of clocks, flowers, and maps, etc. Here, language formulation is correct and the spatial arrangements of words are respected, but the hand has lost its skill in forming letters and words. There may be an uncertainty as to how the pen should be held and applied to paper; apraxias (ideomotor and ideational) are present in the right hander. Also worth brief comment is mirror writing, in which script runs in the opposite direction to normal with each letter also being reversed. Some normal individuals have an unusual facility to produce mirror writing, and it has been reported in developmentally delayed left-handed children. Those few instances in which mirror writing is acquired tend to be transient and incomplete with strokes in various parts of the left hemisphere, or rarely, the right hemisphere or bifrontal lesions (see the review by Schott). During the early phases of recovery, spon taneous speech is reduced in amount and is dysfluent; less often, speech is fluent and paraphasic to the point of jargon. This configuration has been termed "mixed transcortical aphasia," a syndrome originally described in bilateral border-zone infarctions or large left-frontal lesions. Complete recovery in a matter of weeks is the rule unless the underlying cause is a tumor. The head of the caudate, ante rior limb of the internal capsule, or the anterosuperior aspect of the putamen are the structures involved in dif ferent patients. The aphasia is characterized by nonflu ent, dysarthric, paraphasic speech and varying degrees of difficulty with comprehension of language, naming, and repetition. The lesion is vascular as a rule, and a right hemiparesis is usually associated with it. In addition to the neurologic forms of agraphia, described above, psychologists have defined a group of linguistic agraphias, subdivided into phonologic, lexical, In general, and semantic types. These linguistic models are based on loss of the ability to write (and to spell) particular classes of words. For example, the patient may be unable to spell pronounceable nonsense words, with preserved ability to spell real words (phonologic agraphia); or there may be preserved ability to write nonsense words but not irregular words, such as striatocapsular aphasia recovers more slowly and less completely than thalamic aphasia. These two subcortical aphasias, thalamic and striata capsular, resemble but are not identical to the Wernicke and Broca types of aphasia, respectively. For further discussion, the reader is directed to the articles of Naeser and of Alexander and their colleagues. The orthographic qualities of writing deteriorate in many motor disorders such as Parkinson disease, tremors, dystonias, and spasticity, but careful inspection shows that language content is normal. Pathologic changes in parts of the cerebrum other than the peri sylvian regions may secondarily affect language func tion. Other examples are the lesions in the mediorbital or superior and lateral parts of the frontal lobes, which impair all motor activity to the point of abulia or akinetic mutism. If the patient is less severely hypokinetic, his speech tends to be laconic, with long pauses and an inability to sustain a monologue. Extensive occipital lesions will, of course, impair reading, but they also reduce the utilization of all visual and lexical stimuli. Deep cerebral lesions, by causing fluctuating states of inattention and disorientation, induce fragmentation of words and phrases and sometimes protracted, uncontrol lable talking (logorrhea). The nonaphasic language disor ders of the confusional states, emphasized by Geschwind, have already been mentioned. Also common in global or multifocal cerebral dis eases are defects in prosody, both expressive and recep tive. These appear in numerous states that affect global cerebral function, such as Alzheimer disease as well as with lesions of the nondominant (right) perisylvian region, as noted in Chap. The methods of language rehabilitation are special ized, and it is advisable to call in a person who has been trained in this field. However, inasmuch as a part of the benefit is also psychologic, an interested family member or schoolteacher can be of help if a speech therapist is not available in the community. Frustration, depression, and paranoia, which complicate some aphasias, may require psychiatric evaluation and treatment. The developmental language disorders of children pose special problems and are considered in Chap. In general, recovery from aphasia that is due to cerebral trauma is usually faster and more complete than that from aphasia because of stroke. The various dis sociative speech syndromes and pure word mutism also tend to improve rapidly and often completely. In general, the outlook for recovery from any particular aphasia is more favorable in a left-handed person than in a right handed one.

Crystalline DMSO (Msm (Methylsulfonylmethane)). Azithromycin.

- What other names is Msm (methylsulfonylmethane) known by?

- What is Msm (methylsulfonylmethane)?

- Osteoarthritis. Taking MSM by mouth seems to modestly reduce some symptoms of arthritis such as pain and joint movement, but it might not reduce other symptoms such as stiffness.

- Dosing considerations for Msm (methylsulfonylmethane).

- How does Msm (methylsulfonylmethane) work?

- Are there safety concerns?

- Chronic pain, muscle and bone problems, snoring, allergies, scar tissue, stretch marks, wrinkles, protection against sun/wind burn, eye swelling, dental disease, wounds, cuts, hayfever, asthma, stomach upset, constipation, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), mood elevation, obesity, poor circulation, hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes mellitus type 2 (NIDDM), and other conditions.

Source: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=96524

Azithromycin 250mg free shipping

Initially the j erks are ran dom but late in the disease they may attain an almost rhythmic and symmetric character antibiotics for acne initial breakout buy cheap azithromycin 100 mg online. In addition there is an exaggerated startle response, and violent myoclonus may be elicited by tactile, auditory, or visual stimuli in advanced stages of the disease. In this condition too, there is a progressive destruction of neurons, mainly but not exclusively in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices, and a striking degree of gliosis. In addition to parenchy mal destruction, the cortical tissue shows a fine-meshed vacuolation, hence the designation subacute spongiform encephalopathy. In yet another group of myoclonic dementias, the most prominent associated abnormality is a progressive deterioration of intellect. Like the myoclonic epilepsies, the myoclonic dementias may be sporadic or familial and may affect both children and adults. The notion that monophasic-restricted myoclonus always emanates from the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, or brain stem cannot be sustained, as there are forms that are traceable to a purely spinal cause. The problem takes the form of an almost continuous arrhythmic jerking of a restricted group of muscles, often on one side of the body. Such a subacute spinal myoclonus of obscure origin was described many years ago by Campbell and Garland, and similar cases continue to be cited in the literature. We have seen several in which myoclonus was isolated to the musculature of the abdominal or thoracic wall on one side or to the legs; only rarely were we able to establish a cause, and the spinal fluid has been normal. This form has been referred to as "propriospinal" when it involves repetitive flexion or extension myoclonus of the torso that is aggravated by stretching or action. Examples of myelitis with irregular and strictly seg mental myoclonic jerks (either rhythmic or arrhythmic) have been reported in humans and have been induced in animals by the Newcastle virus. In our experi ence, this type of myoclonus has occurred following zos ter myelitis, postinfectious transverse myelitis, and rarely with multiple sclerosis, epidural cord compression, or after traumatic spinal injury. A paraneoplastic form has also been described, usually associated with breast cancer (Chap. When highly ionic contrast media was in the past used for myelography, painful spasms and myoclo nus sometimes occurred in segments where the dye was concentrated by a block to the flow of spinal fluid. Treatment is difficult and one resorts to a combina tion of antiepileptic drugs and benzodiazepines, just as in cerebral myoclonus. The glycine inhibitor levetiracetam reportedly has been successful when other drugs have failed (Keswani et al). When the patient is relaxed, the limb and other skeletal muscles are quiet (except in the most severe cases); only seldom does the myoclonus appear during slow, smooth (ramp) movements. Only the limb that is moving is involved; hence it is a localized, stimulus evoked myoclonus. Speech may be fragmented by the myoclonic jerks, and a syllable or word may be almost compulsively repeated, as in palilalia. Lance and Adams found the irregu lar discharges to be transmitted via the corticospinal tracts, preceded in some cases by a discharge from the motor cortex. Chadwick and coworkers postulated a reticular loop reflex mechanism, while Hallett and col leagues (1977) found that a cortical reflex mechanism was operative in some cases and a reticular reflex mechanism in others. Several clinical trials and case reports have suggested that the antiepileptic levitiracetam may be useful (Krauss et al, 2001). Sensory relationships are a prominent fea ture of polymyoclonus, particularly those related to metabolic disorders, and will eventually shed some light on the mechanism. Repeated stimuli may recruit a series of incremental myoclonic jerks that culmi nate in a generalized convulsion, as often happens in the familial myoclonic syndrome of Unverricht-Lundborg. Conversely, it is just as likely that these potentials origi nate from subcortical structures that project both to the descending motor pathways and upward to the cortex. In humans, the indication is that postanoxic action myoc lonus has its basis in reflex hyperactivity of the reticular formation and that the only consistent damage is in the cerebellum rather than in the cerebral cortex (see above, under "Intention or Action Myoclonus"). As already noted, several types of myoclonus are closely coupled with cerebellar cortical degenerations. Pathologic examinations have been of little help in determining the essential sites of this unstable neuronal discharge because in most cases, the neuronal disease is so diffuse. Nonetheless, the most restricted lesions associated with myoclonus are located in the cerebellar cortex, dentate nuclei, and pretectal region. Trihexyphenidyl or benzotro pine, in high doses, may allow some amelioration but they are difficult to tolerate. In the past decade, the use of deep brain stimulation has found some success in the treatment of idiopathic cervical dystonia. The internal segments of the globus pallidus and the subthalamic nuclei have been used as targets. This approach is certainly preferable to the former use of ablative lesions in these areas and in the thalami. In the most severe cases and those refractory to treatment with botulinum toxin, a combined sectioning of the spinal accessory nerve and of the first three cervi cal motor roots bilaterally has been successful in reducing spasm of the muscles without totally paralyzing them. Considerable relief has been achieved for as long as 6 years in one-third to one-half of cases treated in this way (Krauss et al; Ford et al). Blepharospasm Patients in mid and late adult life, predominantly women, may present with the complaint of inabil ity to keep their eyes open that is a manifestation of involuntary closure of the eyelids. During conversation, the patient struggles to overcome the spasms and is distracted by them. Reading and watching television are impossible at some times but surprisingly easy at others. Jankovic and Orman in a survey of 250 such patients found that 75 percent pro gressed in severity over the years to the point, in about 1 5 percent of cases, of making the patients functionally blind. Some instances of blepharospasm are a compo nent of the Meige syndrome that includes jaw spasms (see next section). However, the spasms persist in dim light and even after anesthesia of the cor neas. Blepharospasm may occur as an isolated phenomenon, but just as often it is combined with oromandibular spasms and sometimes with spasmodic dysphonia, torticollis, and other dystonic fragments. With the exception of a depressive reaction in some patients, psychiatric symptoms are lacking, and the use of psychotherapy, biofeedback, acupuncture, behavior modification therapy, and hypnosis has gener ally failed to cure the spasms. No neuropathologic lesion or neurochemical profile has been established in any of these disorders (Marsden et al; see also Hallett). Finally, eye closure with fluttering of the lids in patients with a high degree of suggestibility is usually indicative of a psychological disorder. Blepharospasm induced by pain from ocular conditions such as iritis and rosacea of the eyelids has already been mentioned. Lingual, Facial, and Oromandibular Spasms these special varieties of involuntary movements also appear in later adult life, with a peak age of onset in the sixth decade. Common terms for this condition are Meige syn drome, after the French neurologist who gave an early description of it, and Brueghel syndrome, because of the similarity of the grotesque grimace to that of a subject in a Brueghel painting called De Gaper. Difficulty in speak ing and swallowing (spastic or spasmodic dysphonia) and blepharospasm are also frequently conjoined, and occasionally patients with these disorders develop torti collis or dystonia of the trunk and limbs. All these prolonged, forceful spasms of facial, tongue, and neck muscles have followed the administration of pheno thiazine and butyrophenone drugs. More often, however, the dyskinetic disorder induced by neuroleptics is some what different, consisting of choreoathetotic chewing, lip smacking, and licking movements (tardive orofacial dyskinesia, rabbit-mouth syndrome; see later). In the treatment of blepha rospasm, a variety of antiparkinsonian, anticholinergic, and tranquilizing medications may be tried, but one should not be optimistic about the chances of success. A few of our patients have had temporary and partial relief from L-dopa and we have found it useful to conduct a brief trial in most patients. Sometimes the blepharospasm disappears spontaneously (in 13 percent of the cases in the series of Jankovic and Orman). Thermolytic destruc tion of part of the fibers in the branches of the facial nerves that innervate the orbicularis oculi muscles is reserved for the most resistant and disabling cases. Reflex blepharospasm, as Fisher has called this phenomenon, takes liberty with the term as it more in the character of an apraxia of opening of the lids. A homolateral blepharospasm has also been observed with a small thalamomesencephalic infarct. In one patient there were foci of neuro nal loss in the striatum (Altrocchi and Forno); another patient showed a loss of nerve cells and the presence of Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra and related nuclei (Kulisevsky et al); both are of uncertain significance. A form of focal dystonia that affects only the jaw mus cles has been described (masticatory spasm of Romberg); a similar dystonia may be a component of orofacial and generalized dystonias.

Order line azithromycin

Flexion movements of the hands may then occur arrhythmically once or several times a minute antibiotics for acne resistance azithromycin 500 mg line. The same lapses in sus tained muscle contraction can be provoked in any muscle group-including, for example, the protruded tongue, the closed eyelids, or the flexed trunk muscles. Sometimes, asterixis can be elicited best by asking the patient to place his hand flat on a table and raise the index finger. This sign was first observed in patients with hepatic encephalopathy but was later noted with hypercapnia, uremia, and other metabolic and toxic encephalopathies. Asterixis may also be evoked by phenytoin and other anticonvulsants, usually indicating that these drugs are present in excessive concentrations. Similar rapid lapsing movements of the head or arms sometimes appear dur ing drowsiness in normal persons ("nodding off"). Unilateral asterixis occurs in an arm and leg on the side opposite an anterior thalamic infarction or small hemorrhage, after stereotaxic thalamotomy; and with an upper midbrain lesion, usually as a transient phenom enon after stroke. One-sided or focal myoclonic jerks are the dominant feature of a particular form of childhood epilepsy-so-called benign epilepsy with rolandic spikes (Chap. Myoclonus may be associated with atypi cal petit mal and akinetic seizures in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (absence or petit mal variants); the patient often falls during the brief lapse of postural mechanisms that follows a single myoclonic contraction. These types of special "myoclonic epilepsies" are discussed further below and in Chap. Focal simple myoclonus is also one of the notable fea tures of degenerative neurologic conditions, particularly corticobasal ganglionic degeneration; it is generally seen in a limb that is made rigid by this process. As a result, an arm may suddenly flex, the head may jerk backward or forward, or the trunk may curve or straighten. In this and other forms of myoclonus, the muscle contraction is brief (20 to 50 ms)-i. The speed of the myoclonic contraction is the same whether it involves a part of a muscle, a whole muscle, or a group of muscles. Some of the patients register little complaint, accept ing the constant intrusions of motor activity with sto icism; they generally lead relatively normal, active lives. Occasionally there is hint of a mild cer ebellar ataxia and, in one family studied by R. Adams, essential tremor was present as well, both in family mem bers with polymyoclonus and in those without. Both the tremor and myoclonus were dramatically suppressed by the ingestion of alcohol. In a Mayo Clinic series reported by Aigner and Mulder, 19 of 94 cases of polymyoclonus were of this "essential" type. Several of the sleep-related syndromes that involve repetitive leg movements include an element of myoc lonus. In a few patients, mainly older ones with severe "restless legs syndrome," the myoclonus and dyskinesias may become troublesome in the daytime as well. It was probably in the course of this description that the term myoclonus was used for the first time. Muscles were involved diffusely, particularly those of the lower face and proximal segments of the limbs, and the myoclonus persisted for many years, being absent only during sleep. Over the years, the term paramyoclonus multiplex, or polymyoclonus has been applied to all varieties of myo clonic disorder (and other motor phenomena as well), to the point where it has nearly lost its specific connotation. Polymyoclonus may occur in pure or "essential" form as a benign, often familial, nonprogressive disease or as part of a more complex progressive syndrome that may prove disabling and fatal. More importantly, there are several acquired forms that are associated with various neurologic diseases as discussed below. The myoclonus takes the form of irregular twitches of one or another part of the body, involving groups of muscles, single muscles, or even a Myoclonic epilepsy constitutes an important syndrome of multiple etiologies. A relatively benign idiopathic form, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, has been mentioned and is discussed extensively in Chap. A more seri ous type of myoclonic epilepsy, which in the beginning may be marked by polymyoclonus as an isolated phe nomenon, is eventually associated with dementia and other signs of progressive neurologic disease (familial variety of Unverricht and Lundborg). An outstanding feature of the latter is a remarkable sensitivity of the myoclonus to stimuli of all sorts. If a limb is passively or actively displaced, the resulting myoclonic jerk may lead, through a series of progressively larger and more or less synchronous jerks, to a generalized convulsive seizure. In late childhood this type of stimulus-sensitive myoclonus is usually a manifestation of the juvenile form of lipid storage disease, which, in addition to myoclonus, is char acterized by seizures, retinal degeneration, dementia, rigidity, pseudobulbar paralysis, and, in the late stages, by quadriplegia in flexion. Another form of stimulus-sensitive (reflex) myoclo nus, inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, begins in late childhood or adolescence and is associated with neu ronal inclusions (Lafora bodies thus Lafora-body disease) in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex and in brainstem nuclei. Unlike Lafora-body disease, the Baltic variety of myoclonic epilepsy has a favorable prognosis, particularly if the seizures are treated with valproic acid. Under the title of cherry-red-spot myoclonus syn drome, Rapin and associates have drawn attention to a familial (autosomal recessive) form of diffuse, incapaci tating intention myoclonus associated with visual loss and ataxia. The earliest sign is a cherry-red spot in the macula that may fade in the chronic stages of the illness. The specific enzyme defect appears to be a deficiency of lysosomal alpha-neu roaminidase (sialidase), resulting in the excretion of large amounts of sialylated oligosaccharides in the urine. This has been referred to as type 1 sialidosis to distinguish it from a second type, in which patients are of short stature (as a result of chondrodystrophy) and often have a defi ciency of beta-galactosidase in tissues and body fluids. In patients with sialidosis, a mucopolysaccharide-like material is stored in liver cells, but neurons show only a nonspecific accumulation of lipofuscin. A similar clinical syndrome of myoclonic epilepsy is seen in a variant form of neuroaxonal dystrophy and in the late childhood-early adult neuronopathic form of Gaucher disease, in which it is associated with supranuclear gaze palsies and cerebel lar ataxia (Chap. A subacute encephalopathy with dif fuse myoclonus may occur in association with the auto antibodies that are characteristically a component of Hashimoto thyroiditis and also in Whipple disease (both are discussed in Chap. An acute onset of polymyoclo nus with confusion occurs with lithium intoxication; once ingestion is discontinued, there is improvement (slowly over days to weeks) and the myoclonus is replaced by diffuse action tremors, which later subside. Diffuse, severe myoclonus may be a prominent feature of early tetanus and strychnine poisoning. Polymyoclonus that occurs in the acute stages of anoxic encephalopathy should be distinguished from postanoxic action or intention myoclonus that emerges with recovery from cardiac arrest or asphyxiation (it is discussed below and in Chap. The factor common to all these disorders is the presence of diffuse neuronal disease. Cerebral hypoxia (acute and severe) Uremia Hashimoto thyroiditis Lithium intoxication Haloperidol and sometimes phenothiazine intoxication Hepatic encephalopathy (rare) Cyclosporine toxicity Nicotinic acid deficiency encephalopathy Tetanus Other drug toxicities Focal and spinal forms of myoclonus Herpes zoster myelitis Other unspecified viral myelitis Multiple sclerosis Traumatic spinal cord injury Arteriovenous malformation of spinal cord Subacute myoclonic spinal neuronitis Paraneoplastic spinal myoclonus Myoclonus in association with signs of cerebellar incoordination, including opsoclonus (rapid, irregular, but predominantly conjugate movements of the eyes in all planes as described in Chap. Many of the childhood cases are associated with occult neuroblas toma, and some have responded to the administration of corticosteroids. In adults, a similar syndrome has been described as a remote effect of carcinoma (mainly of lung, breast, and ovary as discussed at length in Chap. As mentioned above, diffuse myoclonus is a promi nent and often early feature of the prion transmis sible illness Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, characterized by rapidly progressive dementia, disturbances of gait and coordination, and all manner of mental and visual aberrations (see Chap. A combination of several of these medications is usually required to make the patient functional. In the cases described by Thompson and colleagues, the problem began with brief periods of spasm of the pterygoid or masseter muscle on one side. Early on, the differential diagnosis includes bruxism, hemifacial spasm, the odd rhythmic jaw move ments associated with Whipple disease, and tetanus. As the illness progresses, forced opening of the mouth and lateral deviation of the jaw may last for days and adven titious lingual movements may be added. An intermittent spasm that is confined to one side of the face (hemifacial spasm) is not, strictly speak ing, a dystonia and is considered with disorders of the facial nerve in Chap. In patients with Parkinson disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, or Wilson disease and with other lesions in the rostral brainstem, light closure of the eyelids may induce blepha rospasm and an inability to open the eyelids voluntarily. We have seen an instance of blepharospasm as part of paraneoplastic midbrain encephalitis, and there have been several reports of it with autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus but the mechanism in these cases is as obscure as for the idiopathic variety. High doses of benztropine and related anticholinergic drugs may be helpful, but are not as good as botulinum toxin treatment. Many other drugs have been used in the treatment of these craniocervical spasms, but none has effected a cure. Berardelli et al have reviewed other theories pertaining to the physiology of the focal dystonias. It had been claimed that the patient can be helped by a decondition ing procedure that delivers an electric shock whenever the spasm occurs or by biofeedback, but these forms of treatment have not been rigorously tested and have been largely abandoned in favor of botulinum treatments. Men and women are equally affected, most often between the ages of 20 and 50 years. The spasm may be painful and c an spread into the forearm or even the upper arm and shoulder.

Buy discount azithromycin 100mg on-line

The patient with a head injury may also have suffered a fracture of the cervical vertebrae antibiotics for dogs for sale purchase 500 mg azithromycin with visa, in which case caution must be exercised in moving the head and neck as well as in intubation lest the spinal cord be inadvertently damaged. These matters are discussed in detail further on, under "Management of the Acutely Comatose Patient. Persons who accompany the comatose patient to the hospital should be encouraged to remain until they have been questioned. A large number of com pounds may reduce alertness to the point of profound somnolence or stupor, particularly if there are underlying medical problems. Prominent in lists of iatrogenic drug intoxications are anesthetics, sedatives, antiepileptic drugs, opiates, certain antibiotics, antide pressants, and antipsychosis compounds. Chronic admin istration of nitroprusside for hypertension can induce stupor from cyanide toxicity. From an initial survey, many of the common causes of coma, such as severe head injury, alcoholism or other forms of drug intoxication, and hyper tensive brain hemorrhage, are readily recognized. Fever is most often the result of a systemic infection such as pneumonia or bacterial meningitis or viral encephalitis. Fever should not be too easily ascribed to a brain lesion that has disturbed the temperature-regulating center, so-called central fever, which is a rare occurrence. Hypothermia is observed in patients with alcohol or barbiturate intoxication, drown ing, exposure to cold, peripheral circulatory failure, advanced tuberculous meningitis, and myxedema. Slaw breathing points to opiate or barbiturate intoxica tion and occasionally to hypothyroidism, whereas deep, rapid breathing (Kussmaul respiration) should suggest the presence of pneumonia, diabetic or uremic acidosis, pulmonary edema, or the less-common occurrence of an intracranial disease that causes central neurogenic hyper ventilation. Diseases that elevate intracranial pressure or damage the brain often cause slow, irregular, or cyclic Cheyne-Stokes respiration. The various disordered patterns of breathing and their clinical significance are described fur ther on. Vomiting at the outset of sudden coma, particularly if combined with pronounced hypertension, is characteristic of cerebral hemorrhage within the hemispheres, brainstem, cerebellum, or subarachnoid spaces. Marked hypertension is observed in patients with cerebral hemorrhage and in hypertensive encephalopathy and in children with mark edly elevated intracranial pressure. Hypotension is the usual finding in states of depressed consciousness because of diabetes, alcohol or barbiturate intoxication, internal hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, dissecting aortic aneurysm, septicemia, Addison disease, or massive brain trauma. The heart rate, if exceptionally slow, suggests heart block from medications such as tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants, or if combined with periodic breathing and hypertension, an increase in intracranial pressure. Telangiectases and hyperemia of the face and conjunctivae are the common stigmata of alcoholism; myxedema imparts a characteristic puffiness of the face, and hypopituitarism an equally characteris tic sallow complexion. A macular-hemorrhagic rash indicates the possibility of meningococcal infection, staphylococcal endocarditis, typhus, or Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Excessive sweating suggests hypoglycemia or shock, and excessively dry skin, diabetic acidosis, or uremia. Large blisters, sometimes bloody, may form over pres sure points such as the buttocks if the patient has been motionless for a time; this sign is particularly characteris tic of the deeply unresponsive and prolonged motionless state of acute sedation, alcohol and opiate intoxication. The spoiled-fruit odor of diabetic ketoacidotic coma, the uriniferous odor of uremia, the musky and slightly fecal fetor of hepatic coma, and the burnt almond odor of cyanide poisoning are dis tinctive enough to be identified by physicians who possess a keen sense of smell. The predominant postures of the limbs and body; the presence or absence of spontaneous movements on one side; the position of the head and eyes; and the rate, depth, and rhythm of respiration each give substan tial information. By gradually increas ing the strength of these stimuli, one can roughly estimate both the degree of unresponsiveness and changes from hour to hour. Vocalization may persist in stupor and is the first response to be lost as coma appears. Grimacing and deft avoidance movements of stimulated parts of the body are preserved in stupor; their presence substanti ates the integrity of corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts. These signs have been elegantly summarized by Fisher based on his own observations. The widely adopted Glasgow Coma Scale, constructed originally as a quick and simple means of quantitating the responsiveness of patients with cerebral trauma, can be used in the grading of other acute coma-producing diseases as mentioned earlier in this chapter (see also Chap. It is usually possible to determine whether coma is associated with meningeal irritation. In all but the deep est stages of coma, meningeal irritation from either bacte rial meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage will cause resistance to the initial excursion of passive flexion of the neck but not to extension, turning, or tilting of the head. Meningismus is a fairly specific but somewhat insensitive sign of meningeal irritation as commented in Chap. In the infant, bulging of the anterior fontanel is at times a more reliable sign of meningitis than is a stiff neck. A temporal lobe or cerebellar herniation or decere brate rigidity may also create resistance to passive flexion of the neck and be confused with meningeal irritation. A coma-causing lesion in a cerebral hemisphere can be detected by careful observation of spontaneous move ments, responses to stimulation, prevailing postures, and by examination of the cranial nerves. Hemiplegia is revealed by a lack of restless movements of the limbs on one side and by inadequate protective movements in response to painful stimuli. The weakened limbs are usually slack and, if lifted from the bed, they "fall flail. A lesion in one cerebral hemisphere causes the eyes to be turned away from the paralyzed side (toward the lesion, as described below); the opposite occurs with brainstem lesions. In most cases, a hemiplegia and an accompanying Babinski sign are indicative of a contralateral hemispheral lesion; but with lateral mass effect and compression of the opposite cerebral peduncle against the tentorium, extensor posturing, a Babinski sign, and weakness of arm and leg may appear ipsilateral to the lesion (the earlier-mentioned Kernahan-Woltman sign). A moan or grimace may be provoked by painful stimuli applied to one side but not to the other, reflecting hemianesthesia. Of the various indicators of brainstem function, the most useful are pupillary size and reactivity, ocular move ments, oculovestibular reflexes and, to a lesser extent, the pattern of breathing. These functions, like consciousness itself, are dependent on the integrity of structures in the midbrain and rostral pons. As a transitional phenomenon, the pupil may become oval or pear-shaped or appear to be off center (corec topia) because of a differential loss of innervation of a portion of the pupillary sphincter. The light-unreactive pupil continues to enlarge to a size of 6 to 9 mm diameter and is soon joined by a slight outward deviation of the eye. In unusual instances, the pupil contralateral to the mass may enlarge first; this has reportedly been the case in 10 percent of subdural hematomas but has been far less frequent in our experience. As midbrain displacement continues, both pupils dilate and become unreactive to light, probably as a result of compression of the oculomo tor nuclei in the rostral midbrain (Rapper, 1990). The last step in the evolution of brainstem compression tends to be a slight reduction in pupillary size on both sides, to 5 mm or smaller. Normal pupillary size, shape, and light reflexes indicate integrity of midbrain structures and direct attention to a cause of coma other than a mass. Pontine tegmental lesions cause extremely miotic pupils (<1 mm in diameter) with barely perceptible reaction to strong light; this is characteristic of the early phase of pon tine hemorrhage. The ipsilateral pupillary dilatation from pinching the side of the neck (the ciliospinal reflex) is usu ally lost in brainstem lesions. The Homer syndrome (miosis, ptosis, and reduced facial sweating) may be observed ipsi lateral to a lesion of the brainstem or hypothalamus or as a sign of dissection of the internal carotid artery. With coma caused by drug intoxications and intrin sic metabolic disorders, pupillary reactions are usually spared, but there are notable exceptions. Serum concen trations of opiates that are high enough to cause coma have as a consistent sign pinpoint pupils, with constric tion to light that may be so slight that it is detectable only with a magnifying glass. High-dose barbiturates may act similarly, but the pupillary diameter tends to be 1 mm or more. Systemic poisoning with atropine or with drugs that have atropinic qualities, especially the tricyclic anti depressants, is characterized by wide dilatation and fix ity of the pupils. Hippus, or fluctuating pupillary size, is occasionally characteristic of metabolic encephalopathy. A unilaterally enlarged pupil is an early indicator these are altered in a variety of ways in coma. In light coma of metabolic origin, the eyes rove conjugately from side to side in seemingly random fashion, sometimes resting briefly in an eccentric position. These movements disappear as coma deepens, and the eyes then remain motionless and slightly exotropic. A lateral and slight downward deviation of one eye suggests the presence of a third-nerve palsy, and a medial deviation, a sixth-nerve palsy. During a focal seizure the eyes turn or jerk toward the convuls ing side (opposite to the irritative focus).

Cheap 250mg azithromycin fast delivery