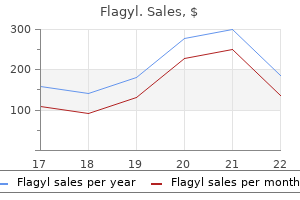

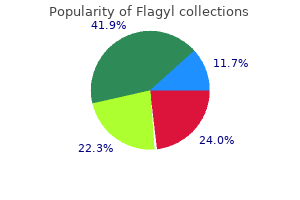

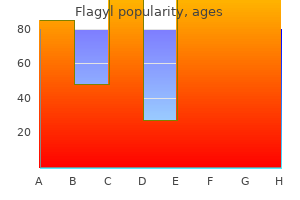

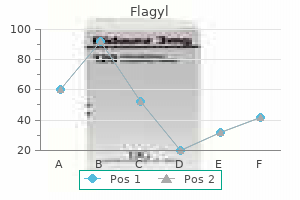

Order flagyl amex

The density of its fibre meshwork antibiotics for acne infection purchase flagyl overnight delivery, and therefore its physical properties, varies with different parts of the body, and with age and gender. The dermis is vital for the survival of the epidermis, and important morphogenetic signals are exchanged at the interface between the two both during development and postnatally. The dermis can be divided into two zones: a narrow, superficial papillary layer and a deeper reticular layer. Basal layer melanocytes and scattered dermal cells (possibly of neural origin) are also positive for S100. Two major categories of cell are present in postnatal dermis, permanent and migrant, as is typical of all general connective tissues. The permanent resident cells include cells of organized structures such as nerves, vessels and cells of the arrector pili muscles, and the fibroblasts, which synthesize all components of the dermal extracellular matrix. It is well differentiated in the limbs and the perineum, but is thin where it passes over the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet, the sides of the neck and face, around the anus, and over the penis and scrotum. It is almost absent from the external ears and atypical in the scalp and in the palms and soles. It provides mechanical anchorage, metabolic support and trophic maintenance to the overlying epidermis, as well as supplying sensory nerve endings and blood vessels. Lying under each epidermal surface ridge are two longitudinal rows of papillae, one on either side of the epidermal rete pegs, through which the sweat ducts pass on the way to the surface. Hairs Hairs are filamentous cornified structures present over almost the entire body surface. Hairs are absent from several areas of the body, including the thick skin of the palms, soles, the flexor surfaces of the digits, the thin skin of the umbilicus, nipples, glans penis and clitoris, the labia minora and the inner aspects of the labia majora and prepuce. The presence, distribution and relative abundance of hair in certain regions such as the face (in males), pubis and axillae, are secondary sexual characteristics that play a role in socio-sexual communication. There are individual and racial variations in density, form, distribution and pigmentation. Hair density varies from approximately 600 per cm2 on the face to 60 per cm2 on the rest of the body. In length, hairs range from less than a millimetre to more than a metre, and in width from 0. They can be straight, coiled, helical or wavy, and differ in colour depending on the type and degree of pigmentation. Curly hairs tend to have a flattened cross-section, and are weaker than straight hairs. Over most of the body surface, hairs are short and narrow (vellus hairs) and in some areas these hairs do not project beyond their follicles. In other regions they are longer, thicker and often heavily pigmented (terminal hairs); these include the hairs of the scalp, the eyelashes and eyebrows, and the postpubertal skin of the axillae and pubis, and the moustache, beard and chest hairs of males. The presence in females of coarse terminal hairs in a male-like pattern is termed hirsutism and can be familial or a sign of an endocrine disorder involving excess androgen production. Reticular layer the reticular layer merges with the deep aspect of the papillary layer. Its bundles of collagen fibres are thicker than those in the papillary layer and form a strong but deformable three-dimensional lattice that contains a variable number of elastic fibres. The predominant parallel orientation of the collagen fibres may be related to the local mechanical forces on the dermis and may be involved in the development of skin lines. Hair follicle Hypodermis the hypodermis (tela subcutanea; subcutaneous tissue) is a layer of loose connective tissue of variable thickness that merges with the deep aspect of the dermis. It is often adipose, particularly between the dermis and musculature of the body wall. It mediates the increased mobility of the skin, and its adipose component contributes to thermal insulation, acts as a shock absorber and constitutes a store of metabolic energy. Subcutaneous nerves, vessels and lymphatics travel in the hypodermis, their main trunks lying in its deepest layer, where adipose tissue is sparse. In the head and neck, the hypodermis also contains striated muscles, such as platysma, which are remnants of more extensive sheets of skin-associated musculature found in other mammals (panniculus adiposus). The amount and distribution of subcutaneous fat varies according to gender: it is generally more abundant and more widely distributed in females, whereas it diminishes from the trunk to the extremities in males. The total amount of subcutaneous fat tends to increase in both males and females in middle age. It may extend deep (3 mm) into the hypodermis, or may be superficial (1 mm) within the dermis. Typically, the long axis of the follicle is oblique to the skin surface; with curly hairs it is also curved. There are cycles of hair growth and loss, during which the follicle presents with different appearances. The hair follicle, hair shaft and hair root extend E almost vertically through the field, the follicle joining the interfollicular epidermis (E). The acini (A) of a sebaceous gland, which is also sectioned tangentially through its capsule (centre bottom, below the portion of the hair follicle in section), open into the follicle in centre field. A dermal hair papilla invaginates the bulb, and along the basal layer of the epidermis, at its interface with the dermis, melanocytes insert their dendrites among the keratinocytes forming the hair. The dermal hair papilla invaginates the bulb from its fibrous outer sheath, carrying a loop of capillaries. Melanocytes in the germinal matrix (equivalent to the basal layer of interfollicular epidermis) extend dendrites into the adjacent layers of keratinocytes, to which they pass melanosomes. During the resting or telogen phase, the inferior segment of the follicle is absent. The innermost part is the inferior segment, which includes the hair bulb region extending up to the level of attachment of the arrector pili muscle at the follicular bulge. Between this point and the site of entry of the sebaceous duct is the isthmus, above which is the infundibulum, or dermal pilary canal, which is continuous with the intraepidermal pilary canal. Below the sebaceous duct, the hair shaft and follicular wall are closely connected, and towards the upper end of the isthmus the hair becomes free in the pilary canal. A thick, specialized basal lamina, the glassy membrane, marks the interface between dermis and the epithelium of large hair follicles. The dermal hair papilla is an important cluster of inductive mesenchymal cells, which is required for hair follicle growth in each cycle throughout adult life; it is a continuation of the layer of adventitious mesenchyme that follows the contours of the hair follicle. A hypothetical line drawn across the widest part of the hair bulb divides it into a lower germinal matrix and an upper bulb. The germinal matrix is formed of closely packed, mitotically active pluripotential keratinocytes, among which are interspersed melanocytes and some Langerhans cells. Radially, successive concentric rings of cells give rise to the cortex and cuticle of the hair and, outside this, to the three layers A fully developed hair shaft consists of three concentric zones, which are, from outermost to inner, the cuticle, cortex and medulla. Each has different types of keratin filament proteins and different patterns of cornification. Immature cuticle cells have dense amorphous granules aligned predominantly along the outer plasma membrane with a few filaments. The cortex forms the greater part of the hair shaft and consists of numerous closely packed, elongated squames, which may contain nuclear remnants and melanosomes. Immature cortical cells contain bundles of closely packed filaments but no dense granules, and when fully cornified, they have a characteristic thumbprint appearance with filaments arranged in whorls. The medulla, when present, is composed of loosely aggregated and often discontinuous columns of partially disintegrated cells containing vacuoles, scattered filaments, granular material and melanosomes. When fully differentiated, cells of both layers have a thickened cornified envelope enclosing keratin filaments embedded in a matrix. As they cornify, the cuticle cells of the inner root sheath and hair become interlocked. The distended sebocytes are filled with their oily secretion (sebum), which is discharged into the hair follicle by the holocrine disintegration of secretory cells. Note that the cuticular cells overlap each other; their free ends point towards the apex of the hair. The outer root sheath, beginning at the level of the upper bulb, is a single or double layer of undifferentiated cells containing glycogen. At the isthmus all remaining cell layers of the follicle sheath become flattened, compressed and attenuated.

Purchase flagyl with visa

Axons from cells in the cortex extend through the intermediate zone which becomes cerebral white matter virus january 2014 generic 400mg flagyl overnight delivery. Once the earliest cortical layers have formed, cells originating from the ganglionic eminences migrate tangentially into the cortical layers and form interneurones. The intermediate zone gradually transforms into the white matter of the hemisphere. Meanwhile, other deep progenitor cells produce generations of glioblasts, which also migrate into the more superficial layers. As proliferation wanes and finally ceases in the ventricular and subventricular zones, their remaining cells differentiate into general or specialized ependymal cells, tanycytes or subependymal glial cells. The time of the proliferation of different cortical neurones varies according to their laminar destination and cell type. The first groups of cells to migrate are destined for the deep cortical laminae and later groups pass through them to more superficial regions. The subplate zone is most prominent during mid-gestation; it contains neurones surrounded by a dense neuropil and is the site of the most intense synaptogenesis in the embryonic cortex. The cumulative effect of this radial and tangential growth is evident in a marked expansion of the surface area of the cortex without a comparable increase in its thickness (Rakic 1988, Rakic 2009). Because the head is large at birth, measuring one-quarter of the total body length, the brain is also proportionally larger and constitutes 10% of the body weight, compared with 2% in the adult. The greater part of the increase occurs during the first year, at the end of which the volume of the brain has increased to 75% of its adult volume. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the fifth year and 95% by 10 years, attaining adult size by the seventeenth or eighteenth year, largely as a result of the continuing myelination of various groups of nerve fibres. At full term, the general arrangement of sulci and gyri is present, but the insula is not completely covered, the central sulcus is situated further rostrally, and the lateral sulcus is more oblique than in the adult. Most of the developmental stages of sulci and gyri have been identified in the brains of premature infants. Of the cranial nerves, the olfactory nerve and the optic nerve at the chiasma are much larger than in the adult, whereas the roots of the other nerves are relatively smaller. The cerebral ventricles are larger in the neonatal brain than they are in the adult. As the head moves down the birth canal and is compressed, the cerebrospinal fluid is pushed out into the venous sinuses; this does not happen in a caesarean delivery. B, the main migratory paths of interneurones derived from the three subdivisions of the ganglionic eminence. The pallidum also contributes interneurones to the formation of the cerebral cortex. The vast species differences between invertebrate, murine, nonhuman primate and primate nervous systems have long posed particular, sometimes intractable, problems for neuroscientists exploring the evolution of the human cerebral cortex. Current understanding of the pre- and postnatal events that regulate the numbers of neurones and their associated glia; the dynamics of neuronal migration to proper layers, columns and regions; the enormous expansion of the cortical surface; and the development of connectivity, particularly networks mediating higher cognitive functions and language, remains in its infancy for the human cortex. Although the biological significance of the inside-out gradient of neurogenesis is yet to be established, it is known that, if that gradient is disturbed, by either genetic or epigenetic factors, neurones display abnormal cortical function. The consequences of failure or delay in neuronal migration cause a wide range of disorders, such as lissencephaly, schizophrenia, autism and mental retardation (Wu et al 2014). Studies suggest three successive stages of the human oligodendrocyte lineage (pre-oligodendrocyte, immature oligodendrocyte, and mature oligodendrocyte) in human cerebral white matter between midgestation and term birth (Back et al 2001). Ventrodorsal gradients of oligodendrocyte precursor cell density and of myelination are described in the telencephalon. The sequence of myelination of the motor pathways may explain, at least partially, the order of development of muscle tone and posture in the premature infant and neonate. Myelin appears to start first around longer axons; thus, in the preterm infant, axial extension precedes flexion, whereas finger flexion precedes extension. By term, the neonate at rest has a strong flexor tone accompanied by adduction of all limbs. Neonates also display a distinct preference for a head position facing to the right, which appears to be independent of handling practices and may reflect the normal asymmetry of cerebral function at this Myelination Central nervous system Preterm period (w) 10 20 Fibre growth. Cingulum Association fibres in occipital, frontal, temporal and parietal lobes External capsule Extreme capsule. Comparison of postnatal rates of myelination in human and primate brains shows that humans achieve approximately 60% of adult myelination during adolescence (compared to 96% in chimpanzees). Miller et al (2012) suggest this schedule of neural connectivity in humans might contribute to the development of functional circuitry with greater plasticity and capacity to be shaped by postnatal environmental and social interactions. The greatest delay in myelination is seen in the prefrontal cortex, an area where many neural circuits concerned with learning and memory develop only after sexual maturity has been attained. Reflexes present at birth A number of reflexes are present at birth and their demonstration is used to indicate normal development of the nervous system and responding muscles. Five tests of neurological development are most useful in determining gestational age. The spinal reflex arc is fully developed by the eighth week of gestation and lower limb flexor tone is detectable from about 29 weeks. The Babinski response, which involves extension of the great toe with spreading of the remaining toes in response to stimulation of the lateral aspect of the sole of the foot, is elicited frequently in neonates; it reflects poor cortical control of motor function by the immature brain. Examination of the motor system and evaluation of these reflexes allow assessment of the nervous system in relation to gestational age. The neonate also exhibits complex reflexes, such as nasal reflexes and sucking and swallowing. Infants with a corrected gestational age of 32 weeks or more have a better-developed sucking reflex and are quicker in achieving oral feeding (Neiva et al 2014). An auditory reflex present at term is the production of otoacoustic emissions from sensory cell activity in the inner ear in response to sound and is now routinely tested in neonates as an assessment of normal hearing. Nasal reflexes produce apnoea via the diving reflex, sneezing, sniffing, and both somatic and autonomic reflexes. Stimulation of the face or nasal cavity with water or local irritants produces apnoea in neonates. Breathing stops in expiration, with laryngeal closure, and infants exhibit bradycardia and a lowering of cardiac output. Blood flow to the skin, splanchnic areas, muscles and kidneys decreases, whereas flow to the heart and brain is protected. Different fluids produce different effects when introduced into the pharynx of preterm infants. A comparison of the effects of water and saline in the pharynx showed that apnoea, airway obstruction and swallowing occur far more frequently with water than with saline, suggesting the presence of an upper airway chemoreflex. Reflux of gastric content into the oesophagus is a wellrecognized cause of apnoea and constitutes an acute life-threatening event in infants. Reflex responses to the temperature of the face and nasopharynx are necessary to start pulmonary ventilation. Midwives have, for many years, blown on the faces of neonates to induce the first breath. Sucking and swallowing are a particularly complex set of reflexes, partly conscious and partly unconscious. As a combined reflex, sucking and swallowing require the coordination of several of the 12 cranial nerves. The neonate can, within the first couple of feeds, suck at the rate of once per second, swallow after five or six sucks, and breathe during every second or third suck. Air moves in and out of the lungs via the nasopharynx, and milk crosses the pharynx en route to the oesophagus without apparent interruption of breathing and swallowing, or significant misdirection of air into the stomach or fluids in the trachea. The concept of nonnutritive and nutritive sucking has been introduced to account for the different rates of sucking seen in the neonate. Non-nutritive sucking, when rhythmic negative intraoral pressures are initiated that do not result in the delivery of milk, can be spontaneous or stimulated by an object in the mouth. This type of sucking tends to be twice as fast as nutritive sucking; the sucking frequency for non-nutritive sucking is 1.

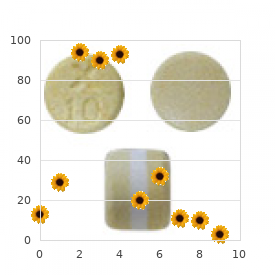

| Comparative prices of Flagyl | ||

| # | Retailer | Average price |

| 1 | Limited Brands | 102 |

| 2 | RadioShack | 161 |

| 3 | Tractor Supply Co. | 526 |

| 4 | Target | 748 |

| 5 | Neiman Marcus | 109 |

Generic flagyl 200mg line

There is also a projection to the lateral reticular nucleus (a precerebellar relay nucleus) antibiotics for sinus infection types purchase flagyl uk. Innocuous cutaneous stimuli may inhibit or excite a particular cell, whereas noxious stimuli are often excitatory. They are concerned with the control of movement, muscle tone and posture, the modulation of spinal reflex mechanisms and the modulation of transmission of afferent information to higher levels. Corticospinal and corticonuclear tracts Corticospinal and corticonuclear fibres arise from neurones in the cerebral cortex. The majority of corticospinal and corticonuclear fibres arise from cells situated in the primary motor cortex (area 4) and the premotor cortex (area 6). Within the grey matter the dotted lines show the laminar pattern, while within the white matter they are an approximate guide to the topography of the tracts. In the monkey, 30% of corticospinal fibres arise from area 4, 30% from area 6, and 40% from the parietal regions. The cells of origin of corticospinal and corticonuclear fibres vary in size according to their cortical origins and are clustered into groups or strips. The largest neurones (giant pyramidal neurones, Betz cells) are located in the primary motor cortex of the precentral gyrus. Corticospinal and corticonuclear fibres descend through the subcortical white matter to enter the genu and posterior limb of the internal capsule. As they continue caudally through the pons, they are separated from its ventral surface and fragmented into fascicles by transversely running pontocerebellar fibres. Corticonuclear fibres leave to terminate in association with the cranial nerve motor nuclei of the midbrain, pons and medulla. In the lumbar and sacral regions, where the dorsal spinocerebellar tract is absent, the lateral corticospinal tract reaches the dorsolateral surface of the cord. As it descends, its fibres terminate in progressively lower spinal segments, which means that the tract diminishes in size. The lateral corticospinal tract also contains some uncrossed corticospinal fibres. The ventral corticospinal tract diminishes as it descends and usually disappears completely at mid-thoracic cord levels. It may either be absent or, internal organization very rarely, contain almost all the corticospinal fibres. Near their termination, most fibres of the tract cross the median plane in the ventral white commissure to synapse on contralateral neurones. The vast majority of corticospinal fibres, irrespective of the tract in which they descend, therefore terminate in the spinal cord on the side contralateral to their cortical origin. Knowledge of the detailed termination of corticospinal fibres is based largely on animal studies, but is supplemented by data from postmortem studies on human brains using anterograde degeneration methods. Experimental evidence shows that precentral corticospinal axons influence the activities of both and motor neurones, facilitating flexor muscles and inhibiting extensors, which are the opposite effects to those mediated by lateral vestibulospinal fibres. Evidence from animal studies shows that direct projections from the precentral cortical areas to spinal motor neurones are concerned with highly fractionated, precision movements of the limbs. Accordingly, in primates, precentral corticospinal fibres are mainly distributed to motor neurones supplying the distal limb muscles. Corticospinal projections may use glutamate or aspartate, often co-localized, as excitatory neurotransmitters. Phylogenetically these fibres represent the oldest part of the corticospinal system. They are concerned with the supraspinal modulation of the transmission of afferent impulses to higher centres, including the motor cortex. Experimental studies in primates indicate that isolated transection of corticospinal fibres at the level of the pyramid (pyramidotomy) results in flaccid paralysis or paresis of the contralateral limbs and loss of independent hand and finger movements. The paralysis is initially flaccid but later becomes spastic, and is most marked in the distal muscles of the extremities, especially those concerned with individual movements of the fingers and hand. The latter is usually interpreted as pathognomonic of corticospinal damage, but it is not always present in patients with confirmed corticospinal lesions. Some of the sequelae of stroke damage in the internal capsule, in particular hyperreflexia and hypertonia, are due to the involvement of other pathways in addition to the corticospinal tract. These include descending cortical fibres to brainstem nuclei, such as the vestibular and reticular nuclei, which also give rise to descending projections that influence motor neurone activity. The terminal zones of the tract correspond to those of corticospinal fibres from the motor cortex. Animal studies demonstrate that the effects of rubrospinal fibres on and motor neurones are similar to those of corticospinal fibres. Tectospinal tract Vestibulospinal tracts the vestibular nuclear complex lies in the lateral part of the floor of the fourth ventricle, at the level of the pontomedullary junction. It descends ipsilaterally, initially in the periphery of the ventrolateral spinal white matter, but subsequently migrating into the medial part of the ventral funiculus at lower spinal levels. Thus, fibres projecting to the cervical, thoracic and lumbosacral segments of the cord arise from neurones in the rostroventral, central and dorsocaudal parts, respectively, of the lateral vestibular nucleus. Unlike the lateral tract, it contains both crossed and uncrossed fibres, and does not extend beyond the mid-thoracic cord level. The vestibular nuclei exert a strong excitatory influence upon the antigravity muscles by way of the medial and lateral vestibulospinal tracts. The antigravity muscles include the epaxial muscles of the vertebral column and the extensor muscles of the lower limbs. Reticulospinal tracts Rubrospinal tract the rubrospinal tract arises from neurones in the caudal magnocellular part of the red nucleus (an ovoid mass of cells situated centrally in the midbrain tegmentum; p. The origin, localization, termination and functions of rubrospinal connections are poorly defined in humans, and the tract appears to be rudimentary. In animals, the tract descends as far as lumbosacral levels, whereas in humans it appears to project only to the upper three the reticulospinal tracts pass from the brainstem reticular formation to the spinal cord. The medullary reticulospinal tract arises from the nucleus gigantocellularis, which lies dorsal to the inferior olivary complex. Terminations of reticulospinal fibres that originate in the medulla are, in general, more dorsally placed than those that originate in the pons, although there is considerable overlap. The course and location of the reticulospinal tracts are poorly defined in humans. Studies in humans have reported that the reticulospinal fibres in general do not form welldefined tracts but are scattered throughout the ventral and lateral columns (Nathan et al 1996). Both and motor neurones are influenced by reticulospinal fibres, through polysynaptic and monosynaptic connections. The pontine reticulospinal tract appears to be tonically active and is excitatory to the antigravity muscles, including the epaxial muscles of the vertebral column and the extensor muscles of the lower limbs. On the other hand, the medullary reticulospinal tract is inhibitory to antigravity muscles. The cells of origin of the medullary reticulospinal tract receive input from the corticospinal tract and the rubrospinal 303 cHapter the tectospinal tract arises from neurones in the intermediate and deep layers of the superior colliculus of the midbrain. They make polysynaptic connections with motor neurones serving muscles in the neck, facilitating those that innervate contralateral muscles and inhibiting those that innervate ipsilateral ones. In animals, unilateral electrical stimulation of the superior colliculus causes turning of the head to the contralateral side, an effect mainly mediated through the tectospinal tract. Descending in the ventral funiculus and ventral part of the lateral funiculus of the cord, these axons terminate on phrenic motor neurones supplying the diaphragm and thoracic motor neurones that innervate intercostal muscles. A pathway with somewhat similar course and terminations to that of the solitariospinal tract originates from the nucleus retroambiguus. Both pathways subserve respiratory activities by driving inspiratory muscles, and some descending axons from the nucleus retroambiguus facilitate expiratory motor neurones.

200 mg flagyl fast delivery

Large myelinated axons are first affected; unmyelinated axons and autonomic fibres escape; and pilo- and vasomotor functions are scarcely affected virus martin garrix cheap flagyl 250mg with mastercard. Slowly progressing ischaemia Conduction block caused either by a haematoma or aneurysm, or by bleeding into compartments produces early and deep autonomic paralysis and loss of power that extends over hours or days, whilst deep pressure sense and some joint position sense persist. These symptoms are seen in war wounds, when nerves become compressed and strangled by scar tissue or by the cicatrix deep to split skin grafts, and may progress over a period of weeks or months. Compression-induced focal paranodal myelin deformation may be involved; experimental studies using a cuff inflated to high pressure around a limb produced slippage of paranodal myelin at nodes of Ranvier lying under the edges of the cuff, i. There was relief of pain but only incomplete recovery so that subsequent flexor to extensor transfer was necessary. Relief of pain and recovery follow rapidly in lesions that have persisted for many months, or even years. Prolonged conduction block of war wounds the characteristic features of classical neurapraxia (see above), caused by the nearby passage of a missile, are likely to be provoked by a momentary displacement or stretching of the nerve trunks. However, a different pattern of conduction block has been recognized in recent conflicts, where the patient is exposed, at close range, to the shock wave of an explosion without any wound or fracture, or signs of significant injury to the soft tissues at the level of the nerve lesion. In these cases, the smallest fibres are most deeply affected and they may not recover. A Degenerative lesions There are essentially two types of degenerative lesion, with very different potentials for recovery. In the second, which approximates to neurotmesis, not only the Schwann cell basal lamina tubes, but also the connective tissue sheaths around the fascicle are interrupted; spontaneous axonal regeneration following this type of injury will be imperfect and disorderly, or may not occur at all. A, the ulnar nerve exposed during flexor muscle slide 8 weeks after supracondylar fracture. The epineurial vessels and also the ulnar recurrent collateral vessels are occluded, and the nerve is compressed by the swollen infarcted muscle. Nerves within a swollen ischaemic limb or tense compartment become compressed and anoxic. Nerves that have become displaced into a fracture or joint are tethered and become subjected to compression, stretching and anoxia. These nerves are not severed by the initial injury; the first lesion is axonotmesis and spontaneous recovery is probable if the cause is removed. However, if this does not happen, the lesion continues to deepen into that of neurotmesis and spontaneous recovery will not occur. Tip of proximal stump Within a few hours of injury, the cut ends of a transected axon seal off, forming end bulbs. The end bulb that forms at the proximal tip of axons in the proximal stump is transformed into a growth cone from which multiple needle-like filopodia and broader sheet-like lamellipodia grow out. The filopodia are rich in actin, and may extend or retract within a matter of minutes. Each axon forms new branches or sprouts: collateral sprouts arise from nodes of Ranvier at levels where the axons are still intact; terminal sprouts arise from the tips of the surviving axons. The axon sprouts and fine cytoplasmic processes derived from their associated Schwann cells form clusters, regenerating units, surrounded by Schwann cell basal laminae. Sprouts within one regenerating unit represent the regenerative effort of one neurone and its axon. Within a few days of injury, the calibre of axons in the proximal stumps is reduced and nerve conduction velocity in the proximal segment falls. A Distal stump During the first 2 or 3 weeks after injury, the constitutive tissue response within a denervated distal stump involves numerous events: some sequential, others consecutive. These include the production of debris, as axons and their myelin sheaths are degraded; an increase in local blood flow; activation of resident macrophages, and recruitment and influx of exogenous macrophages; and proliferation of fibroblasts and Schwann cells. There is a growing consensus that Schwann cells express distinct motor and sensory phenotypes, and that this fundamental difference affects the ability of Schwann cell tubes to selectively support regenerating neurones. For example, expression of osteopontin and clusterin is upregulated in Schwann cells in transected peripheral nerves: the two secreted factors appear to facilitate regeneration of motor or sensory neurones, respectively (Wright et al 2014). While the microenvironment of an acutely denervated distal stump facilitates axonal regrowth because it provides a vascularized segment of longitudinally orientated, laminin-rich basal lamina tubes filled with axon-responsive Schwann cells, a chronically denervated distal stump is associated with poor axonal regeneration and poor functional recovery (Sulaiman and Gordon 2009). Biopsies taken during late repairs, especially when the injury has been complicated by arterial injury or by sepsis, often show remarkably few Schwann cells lying within a densely collagenous matrix. These findings underscore the clinical observation that there is a relatively narrow window of opportunity when surgical intervention is most likely to produce positive results (Lundborg 2000). A, A median nerve extricated from a supracondylar fracture in a 9-year-old girl 3 days after injury; there was complete recovery. B, A median nerve extricated from a supracondylar fracture in a 13-year-old girl 8 weeks after injury; there was no recovery. Not only is the neuronal cell body separated from its continual supply of retrogradely transported neurotrophins, but also its central connections rapidly alter; many neurones thus isolated will die. Amputation provides a model of the effect of permanent axonotomy on the spinal cord: there is extensive loss of neurones in the dorsal root ganglia and in the anterior horn, and a diminution of the large myelinated axons in the ventral and dorsal roots (Dyck et al 1984, Suzuki et al 1993). Neuronal death is more severe in more proximal neurotmesis, and less marked after axonotmesis than after neurotmesis. Neurotmesis in the neonate produces a more rapid and much greater incidence of sensory and motor neurone death than in the adult. The neuronal cell bodies and their axons, investing Schwann cells and associated basal laminae remain intact, healthy and conducting for a long time after the injury. Somatic efferent fibres, being separated from their cell bodies, degenerate; postganglionic autonomic efferent axons also degenerate, as a result of damage to their grey rami communicantes. Healthy myelinated and unmyelinated fibres in the ventral root of the eighth cervical nerve avulsed from the spinal cord 6 weeks previously. The myelinated efferent fibres have undergone Wallerian degeneration and there is a notable increase in the amount of endoneurial collagen. A degenerate efferent myelinated fibre (right) compared with a healthy myelinated afferent fibre (left). After avulsion injury, human dorsal root ganglion neurones show dramatic changes in the expression of genes involved in neurotransmission, trophism, cytokine function, signal transduction, myelination, transcription regulation and apoptosis (Rabert et al 2004). Somewhat counterintuitively, it appears that their expression may be upregulated after injury. Manipulating the many cellular and molecular responses that occur during the injury response in the peripheral nervous system remains an as yet unachieved goal of reconstructive surgery. Reinnervation of muscle spindles and Golgi tendon receptors is generally good after crush lesions (axonotmesis). A muscle spindle may become reinnervated by afferents normally destined for the Golgi tendon organ; many tendon organs remain denervated and the regenerated endings are frequently abnormal in appearance. The reorganization of motor units after repair causes significant alterations in the mechanical input to an individual tendon organ. Muscles usually exhibit weakness, impaired coordination and reduced stamina after nerve repair. There may be selective failure of regeneration of the largest-diameter fibres and of coactivation of the and efferents. The normal movement of joints is brought about by smoothly coordinated and controlled activity in muscles that is precisely and delicately regulated by inhibition and facilitation of the motor neurones. The conversion of an antagonist to an agonist is the basis of musculotendinous transfer; it is common to see patients actively extending the knee or the ankle and toes as soon as the postoperative splint is removed after hamstring to quadriceps transfer or anterior transfer of tibialis posterior. Reinnervated muscles usually fail to convert after muscle transfer, irrespective of their power. Perhaps the defective reinnervation of the deep afferent pathways from the muscle spindles and the tendon receptors blinds muscles, which are, after all, sensory as well as effector organs. Cutaneous sensory receptors similarly undergo a slow degenerative change after denervation and after 3 years they may disappear.

Order flagyl 400 mg online

The plasma membrane of erythrocytes is 60% lipid and glycolipid antimicrobial island dressing cheap flagyl 500 mg online, and 40% protein and glycoprotein. Glycophorins A and B (each with a molecular mass of approximately 50 kDa) span the membrane, and their negatively charged carbohydrate chains project from the outer surface of the cell. The filamentous protein, spectrin, is responsible for maintaining the shape of the erythrocyte. A dimer is formed of 1 and 1 spectrin monomers, and two dimers then come together to form a tetramer (Machnicka et al 2013). These are joined by junctional complexes that contain (among other proteins) ankyrin, short actin filaments, tropomyosin and protein 4. Erythrocyte membrane flexibility also contributes to the normally low viscosity of blood. Molecular defects in the cytoskeleton result in abnormalities of red cell shape, membrane fragility, premature destruction of erythrocytes in the spleen and haemolytic anaemia (Iolascon et al 1998). Fetal erythrocytes up to the fourth month of gestation differ markedly from those of adults, in that they are larger, are nucleated and contain a different type of haemoglobin (HbF). They can interact with naturally occurring or induced antibodies in the plasma of recipients of an unmatched transfusion, causing agglutination and lysis of the erythrocytes. Erythrocytes of a single individual carry several different types of antigen, each type belonging to an antigenic system in which a number of alternative antigens are possible in different persons. Leukocytes also bear highly polymorphic antigens encoded by allelic gene variants. In practice, leukocytes are often divided into two main groups: namely, those with prominent stainable cytoplasmic granules, the granulocytes, and those without. Granulocytes this group consists of eosinophil granulocytes, with granules that bind acidic dyes such as eosin; basophil granulocytes, with granules that bind basic dyes strongly; and neutrophil granulocytes, with granules that stain only weakly with either type of dye. Haemoglobin Haemoglobin (Hb) is a globular protein with a molecular mass of 67 kDa. It consists of globulin molecules bound to haem, an ironcontaining porphyrin group. The oxygen-binding power of haemoglobin is provided by the iron atoms of the haem groups, and these are maintained in the ferrous (Fe++) state by the presence of glutathione within the erythrocyte. The haemoglobin molecule is a tetramer, made up of four subunits, each a coiled polypeptide chain holding a single haem group. Mutations in the haemoglobin chains can result in a range of pathologies (Forget and Bunn 2013). Neutrophil granulocytes Neutrophil granulocytes (neutrophils) are also referred to as polymorphonuclear leukocytes (polymorphs) because of their irregularly Lifespan Erythrocytes last between 100 and 120 days before being destroyed. As erythrocytes age, they become increasingly fragile, and their surface charges decrease as their content of negatively charged membrane glycoproteins diminishes. Aged erythrocytes are taken up by the macrophages of the spleen (Mebius and Kraal 2005) and liver sinusoids, usually without prior lysis, and are hydrolysed in phagocytic vacuoles where the haemoglobin is split into its globulin and porphyrin moieties. Globulin is further degraded to amino acids, which pass into the general amino-acid pool. Iron is removed from the porphyrin ring and either transported in the circulation bound to transferrin and used in the synthesis of new haemoglobin in the bone marrow, or stored in the liver as ferritin or haemosiderin. The remainder of the haem group is converted in the liver to bilirubin and excreted in the bile. The recognition of effete erythrocytes by macrophages appears to take place by a number of mechanisms (Bratosin et al 1998). The neutrophil nucleus is more segmented (four lobes are visible) and the granules are smaller and more electron-dense than in the basophil. Each haemoglobin molecule contains two -chains and two others, so that several combinations, and hence a number of different types of haemoglobin molecule, are possible. For example, haemoglobin A (HbA), which is the major adult class, contains 2 - and 2 -chains; a variant, HbA2 with 2 - and 2 -chains, accounts for only 2% of adult haemoglobin. Haemoglobin F (HbF), found in fetal and early postnatal life, consists of 2 - and 2 -chains. In the genetic condition thalassaemia, only one type of chain is expressed normally, the mutant chain being absent or present at much reduced levels. Thus, a molecule may contain 4 -chains (-thalassaemia) or 4 -chains (-thalassaemia). In haemoglobin S (HbS) of sickle-cell disease, a point mutation in the -chain gene (valine substituted for glutamine) causes the haemoglobin to polymerize under conditions of low oxygen concentration, thus deforming the red blood cell. Conversely, those with group O, universal donors, can give blood to any recipient, since anti-A and anti-B antibodies in the donated blood are diluted to insignificant levels. The Rhesus antigen system is determined by three sets of alleles: namely, Cc, Dd and Ee. Inheritance of the Rh factor also obeys simple Mendelian laws; it is therefore possible for a Rhesus-negative mother to bear a Rhesus-positive child. Under these circumstances, fetal Rh antigens can stimulate the production of anti-Rh antibodies by the mother; as these belong to the IgG class of antibody they are able to cross the placenta. For most of the pregnancy the stroma stops the blood group antibodies from crossing into the fetal circulation. However, immediately prior to birth, the antibodies can cross this barrier and cause destruction of fetal erythrocytes. In the first such pregnancy little damage usually occurs because anti-Rh antibodies have not been induced, but in subsequent Rh-positive pregnancies massive destruction of fetal red cells may result, causing fetal or neonatal death (haemolytic disease of the newborn). Sensitization of the maternal immune system can also result from abortion or miscarriage, or occasionally even from amniocentesis, which may introduce fetal antigens into the maternal circulation. Treatment is by exchange transfusion of the neonate or, prophylactically, by giving Rh-immune (anti-D) serum to the mother after the first Rh-positive pregnancy, which destroys the fetal Rh antigen in her circulation before sensitization can occur. The cells may be spherical in the circulation, but they can flatten and become actively motile within the extracellular matrix of connective tissues. The numerous cytoplasmic granules are heterogeneous in size, shape and content, but all are membrane-bound and contain hydrolytic and other enzymes. Two major types can be distinguished according to their developmental origin and contents. Non-specific or primary (azurophilic) granules are formed early in neutrophil maturation. Specific or secondary granules are formed later, and occur in a wide range of shapes including spheres, ellipsoids and rods. These contain strong bacteriocidal components including alkaline phosphatase, lactoferrin and collagenase, none of which is found in primary granules. In mature neutrophils the nucleus is characteristically multilobed with up to six (usually three or four) segments joined by narrow nuclear strands; this is known as the segmented stage. The earliest to be released under normal conditions are juveniles (band or stab cells), in which the nucleus is an unsegmented crescent or band. In certain clinical conditions, even earlier stages in neutrophil formation, when cells display indented or rounded nuclei (metamyelocytes or myelocytes) may be released from the bone marrow. Neutrophil cytoplasm contains few mitochondria but abundant cytoskeletal elements, including actin filaments, microtubules and their associated proteins, all characteristic of highly motile cells. They can phagocytose microbes and small particles in the circulation and, after extravasation, they carry out similar activities in other tissues. They function effectively in relatively anaerobic conditions, relying largely on glycolytic metabolism, and they fulfil an important role in the acute inflammatory phase of tissue injury, responding to chemotaxins released by damaged tissue. Phagocytosis of cellular debris or invading microorganisms is followed by fusion of the phagocytic vacuole with granules, which results in bacterial killing and digestion. Actively phagocytic neutrophils are able to reduce oxygen enzymatically to form reactive oxygen species including superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide, which enhance bacterial destruction probably by activation of some of the granule contents (Segal 2005, Nathan 2006). Phagocytosis is greatly facilitated by circulating antibodies to molecules such as bacterial antigens, which the body has previously encountered. Antibodies coat the antigenic target and bind the plasma complement protein, C1, to their non-variable Fc regions. This activates the complement cascade, which involves some 20 plasma proteins synthesized mainly in the liver, and completes the process of opsonization.

Syndromes

- Brain (acoustic neuroma, childhood brain tumors)

- Help with financial and social issues

- Surgery to treat eyelid drooping or eyes that are not aligned

- Difficulty falling asleep

- Have the person breathe through the mouth. The person should not breathe in sharply. This may force the object in further.

- Barium enema

- Complete blood count

Generic flagyl 250mg mastercard

Each axon branches near its terminal to innervate from several to hundreds of muscle fibres bacteria 100x buy flagyl 200 mg low cost, the number depending on the precision of motor control required (Shi et al 2012). The detailed structure of a motor terminal varies with the type of muscle innervated. Two major types of ending are recognized, innervating either extrafusal muscle fibres or the intrafusal fibres of neuromuscular spindles. In the latter type, the axon gives off numerous branches that form a cluster of small expansions extending along the muscle fibre; in the absence of propagated muscle excitation, these excite the fibre at several points. Both types of ending are associated with a specialized receptive region of the muscle fibre, the sole plate, where a number of muscle cell nuclei are grouped within the granular sarcoplasm. The sole plate contains numerous mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complexes. The axon terminal contains mitochondria and many clear, 60 nm spherical vesicles similar to those in presynaptic boutons, which are clustered over the zone of membrane apposition. It is ensheathed by Schwann cells whose cytoplasmic projections extend into the synaptic cleft. Endings of fast and slow twitch muscle fibres differ in detail: the sarcolemmal grooves are deeper, and the presynaptic vesicles more numerous, in the fast fibres. When the depolarization of the sarcolemma reaches a particular threshold, it initiates an action potential in the sarcolemma, which is then propagated rapidly over the whole cell surface and also deep within the fibre via the invaginations (T-tubules) of the sarcolemma, causing contraction. Thus the contraction of a muscle fibre is controlled by the firing frequency of its motor neurone. Neuromuscular junctions are partially blocked by high concentrations of lactic acid, as in some types of muscle fatigue. Dynamic - and -efferents innervate dynamic bag1 intrafusal fibres, whereas static - and -efferents innervate static bag2 and nuclear chain intrafusal fibres. Structural and functional studies have demonstrated at least four types of joint receptor; their proportions and distribution vary with site. Type I endings are encapsulated corpuscles of the slowly adapting mechanoreceptor type and resemble Ruffini endings. They lie in the superficial layers of the fibrous capsules of joints in small clusters and are innervated by myelinated afferent axons. Being slowly adapting, they provide awareness of joint position and movement, and respond to patterns of stress in articular capsules. They are particularly common in joints where static positional sense is necessary for the control of posture. A, Whole-mount preparation of teased skeletal muscle fibres (pale, faintly striated, diagonally orientated structures). The terminal part of the axon (silver-stained, brown) branches to form motor end-plates on adjacent muscle fibres. The sole plate recesses in the sarcolemma, into which the motor end-plates fit, are demonstrated by the presence of acetylcholinesterase (shown by enzyme histochemistry, blue). There is no fixed junction with well-defined pre- and postjunctional specializations. Unmyelinated, highly branched, postganglionic autonomic axons become beaded or varicose as they reach the effector smooth muscle. They are packed with mitochondria and vesicles containing neurotransmitters, which are released from the varicosities during conduction of an impulse along the axon. Unlike skeletal muscle, the effector tissue is a muscle bundle rather than a single cell. Cholinergic terminals, which are typical of all parasympathetic and some sympathetic endings, contain clear spherical vesicles like those in the motor end-plates of skeletal muscle. A third category of autonomic neurones has non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic endings that contain a wide variety of chemicals with transmitter properties. These terminals are formed in many sites, including the lungs, blood vessel walls, the urogenital tract and the external muscle layers and sphincters of the gastrointestinal tract. In the intestinal wall, neuronal somata lie in the myenteric plexus, and their axons spread caudally for a few millimetres, mainly to innervate circular muscle. Purinergic neurones are under cholinergic control from preganglionic sympathetic neurones. Autonomic efferents innervate exocrine glands, myoepithelial cells, adipose tissue (noradrenaline (norepinephrine) released from postganglionic sympathetic axons binds to 3-receptors on adipocytes to stimulate lipolysis) and the vasculature and parenchymal fields of lymphocytes and associated cells in several lymphoid organs, including the thymus, spleen and lymph nodes. Macroscopically, as a nerve root is traced towards the spinal cord or the brain, it splits into several thinner rootlets that may, in turn, subdivide into minirootlets. The arrangement of roots and rootlets varies according to whether the root trunk is ventral, dorsal or cranial. Thus, in dorsal roots, the main root trunk separates into a fan of rootlets and minirootlets that enter the spinal cord in sequence along the dorsolateral sulcus. Excitatory and inhibitory synapses on the surfaces of the dendrites and soma cause local graded changes of potential that summate at the axon hillock and may initiate a series of all-or-none action potentials, which in turn are conducted along the axon to the effector terminals. From this mantle, numerous glial processes project into the endoneurial compartment of the peripheral nerve, where they interdigitate with its Schwann cells. They are thought to prevent cell mixing at these interfaces not only by helping dorsal root ganglion afferents navigate their path to targets in the spinal cord but also by inhibiting motoneurone cell bodies exiting to the periphery. The distribution of sodium ions is opposite to that for potassium ions, but at rest the sodium conductance of the membrane is low. Neurones receive, conduct and transmit information by changes in membrane conductance for sodium, potassium, calcium or chloride ions. Increase in the sodium or calcium conductance causes an influx of these ions and results in a depolarization of the cell, while chloride influx or potassium efflux results in hyperpolarization. Plasma membrane permeability to these ions is altered by the opening or closing of ion-specific transmembrane channels, triggered by voltage changes or chemical signals such as transmitters (Catterall 2010). Chemically triggered ionic fluxes may be either direct, where the chemical agent (neurotransmitter) binds to the channel itself to cause it to open, or indirect, where the neurotransmitter is bound by a transmembrane receptor molecule that activates a complex second messenger system within the cell to open separate transmembrane channels. Electrically induced changes in membrane potential depend on the presence of voltage-sensitive ion channels, which, when the transmembrane potential reaches a critical level, open to allow the influx or efflux of specific ions. In all cases, the channels remain open only transiently, and the numbers that open and close determine the total flux of ions across the membrane (Bezanilla 2008). The types and concentrations of transmembrane channels and related proteins, and therefore the electrical activity of the membranes, vary in different parts of the cell. Dendrites and neuronal somata depend mainly on neurotransmitter action and show graded potentials, whereas axons have voltage-gated channels that give rise to action potentials. In graded potentials, a flow of current occurs when a synapse is activated; the influence of an individual synapse on the membrane potential of neighbouring regions decreases with distance. Thus synapses on the distal tips of dendrites may, on their own, have relatively little effect on the membrane potential of the cell body. The electrical state of a neurone therefore depends on many factors, including the numbers and positions of thousands of excitatory and inhibitory synapses, their degree of activation, and the branching pattern of the dendritic tree and geometry of the cell body. The integrated activity directed towards the neuronal cell body is converted to an output directed away from the soma at the site where the axon leaves the cell body, at its junction with the axon hillock. Voltage-sensitive channels are concentrated at this trigger zone, the axon initial segment, and when this region is sufficiently depolarized, an action potential is generated and is subsequently conducted along the axon. Sodium channels within the newly depolarized segment open and positively charged sodium ions enter, driving the local potential inside the axon towards positive values. This inward current in turn depolarizes the neighbouring, downstream, nondepolarized membrane, and the cyclic propagation of the action potential is completed. Several milliseconds after the action potential, the sodium channels are inactivated, a period known as the refractory period. The length of the refractory period determines the maximum frequency at which action potentials can be conducted along a nerve fibre; it varies in different neurones and affects the amount of information that can be carried by an individual fibre.

Discount 250mg flagyl amex

They ramify within the adventitia and antibiotic 300mg buy flagyl with mastercard, in the largest of arteries, penetrate the outermost part of the media. The larger veins are also supplied by vasa vasorum but these may penetrate the wall more deeply, perhaps because of the lower oxygen tension. Nervi vasorum Blood vessels are innervated by efferent autonomic fibres that regulate the state of contraction of the musculature (muscular tone) and thus the diameter of the vessels, particularly the resistance arteries and arterioles. Perivascular nerves branch and anastomose within the adventitia of an artery, forming a meshwork around it. Nerves are occasionally found within the outermost layers of the media in some of the large muscular arteries. Nervi vasorum are small bundles of axons, which are almost invariably unmyelinated and typically varicose. The density of innervation varies in different vessels and in different areas of the body; it is usually sparser in veins and larger lymphatic vessels. Large veins with a pronounced muscle layer, such as the hepatic portal vein, are well innervated. Some vessels in the brain may be innervated by intrinsic cerebral neurones, although neural control of brain vessels is of minor importance compared with metabolic and autoregulation (local response to stretch stimuli). Vasoconstrictor adrenergic fibres release noradrenaline (norepinephrine), which acts on -adrenergic receptors in the muscle cell membrane. In addition, circulating hormones and factors such as nitric oxide, prostaglandins and endothelin, which are released from endothelial cells, exert a powerful effect on the muscle cells. Neurotransmitters reach the muscle from the adventitial surface of the media, whereas hormonal and endothelial factors diffuse from the intimal surface. In a few tissues, sympathetic cholinergic fibres inhibit smooth muscle contraction and induce vasodilation. Vascular smooth muscle exhibits endogenous (myogenic) activity in response to stretch and shear. Most arteries are accompanied by nerves that travel in parallel with them to the peripheral organs that they supply. However, these paravascular nerves are quite independent and do not innervate the vessels they accompany. Pericytes Pericytes are present at the outer surface of capillaries and the smallest venules (postcapillary venules), where an adventitia is absent and there are no muscle cells. They are elongated cells, whose long cytoplasmic processes are wrapped around the endothelium. Pericytes are scattered in a discontinuous layer around the outer circumference of capillaries. They are gradually replaced by smooth muscle cells as vessels converge and increase in diameter. Pericytes are enclosed by their own basal lamina, which merges in places with that of the endothelium. Most display areas of close apposition with endothelial cells, and occasionally form adherens junctions where their basal laminae are absent. Pericyte cytoplasm contains actin, myosin, tropomyosin and desmin, which suggests that they are capable of contractile activity. They also have the potential to act as mesenchymal stem cells, and participate in repair processes by proliferating and giving rise to new blood vessel and connective tissue cells. Pericytes, or closely related cells, may be the source of myofibroblasts that contribute to fibrosis in disease processes (reviewed in Duffield (2012)). Perivascular macrophages are attached to the outer walls of capillaries and to other vessels; they are phenotypically distinct from parenchymal microglia, which are also of monocytic origin. A thin layer of meningeal cells derived from the pia mater surrounds arterioles but disappears at the level of capillaries. They begin as dilated, blind-ended tubes with larger diameters and less regular cross-sectional appearances than those of blood capillaries. The smaller lymphatic vessels are lined by endothelial cells, which have numerous transcytotic vesicles within their cytoplasm and so resemble blood capillaries. However, unlike capillaries, their endothelium is generally quite permeable to much larger molecules: they are readily permeable to large colloidal proteins and particulate material such as cell debris and microorganisms, and also to cells. Permeability is facilitated by gaps between the endothelial cells, which lack tight junctions (discontinuous endothelium), and by pinocytosis. The lymphatic system provides an important transport pathway for leukocytes and defence against infection (reviewed in Saharinen et al (2004)). Lymph is formed from interstitial fluid, which is derived from blood plasma via filtration in the microcirculation. Much of the filtered fluid is reabsorbed by the time the blood leaves the venules, but about 15% or 8 litres per day enters the lymphatics. Lymphatic vessels take up this residual fluid by passive diffusion and the transient negative pressures in their lumina, which are generated intrinsically by contractile activity of smooth muscle in the largest lymphatic vessel walls, and extrinsically by compression of the lymph vessels as a result of contraction of adjacent muscle or arterial pulsation. Lymphatic capillaries are prevented from collapsing by anchoring filaments, which tether their walls to surrounding connective tissue structures and exert radial traction. In most tissues, lymph is clear and colourless; in the lymphatic capillaries it has an identical composition to interstitial fluid. In contrast, lymph from the small intestine is dense and milky, reflecting the presence of lipid droplets (chylomicrons) derived from fat absorbed by the mucosal epithelium. The terminal lymphatic vessels in the mucosa of the small intestine are known as lacteals and the lymph as chyle. Lymphatic capillaries are not ubiquitous: they are not present in cornea, cartilage, thymus, the central or peripheral nervous system or bone marrow, and there are very few in the endomysium of skeletal muscles. Typically, lymph percolates through a series of nodes before Cerebral vessels Major branches of cerebral arteries that lie in the subarachnoid space over the surface of the brain have a thin outer coating of meningeal cells, usually one layer thick, where adjacent meningeal cells are joined by desmosomes and gap junctions. Veins on the surface of the brain have very thin walls, and the smooth muscle layers in the wall are often discontinuous. As arteries enter the subpial space and penetrate the brain, they lose their elastic laminae, and consequently the cerebral cortex and white matter typically contain only arterioles, venules and capillaries. The exceptions are the large penetrating vessels in the basal ganglia, where many arteries retain their elastic laminae and thick smooth muscle media. Enlarged perivascular spaces form around these large arteries in ageing individuals. Arterioles and venules in the cortex and white matter can be distinguished from each other because arterioles are surrounded by a smooth muscle coat, whereas veins and venules have larger lumina and thinner walls. There are exceptions to this arrangement: the lymph vessels of the thyroid gland and oesophagus, and of the coronary and triangular ligaments of the liver, all drain directly to the thoracic duct without passing through lymph nodes. In the larger vessels, a thin external connective tissue coat supports the endothelium. Elastic fibres are sparse in the tunica intima, but form an external elastic lamina in the tunica adventitia. The valves are semilunar, generally paired and composed of an extension of the intima. Their edges point in the direction of the current, and the vessel wall downstream is expanded into a sinus, which gives the vessels a beaded appearance when they are distended. Deep lymphatic vessels usually accompany arteries or veins, and almost all reach either the thoracic duct or the right lymphatic duct, which usually joins the left or right brachiocephalic veins respectively at the root of the neck. The thoracic duct is structurally similar to a medium-sized vein but the smooth muscle in its tunica media is more prominent. Larger vessels have their own plexiform vasa vasorum and accompanying nerve fibres. If their walls are acutely infected (lymphangitis) this vascular plexus becomes congested, marking the paths of superficial vessels by red lines that are visible through the skin and tender to the touch. New vessels form readily after damage, beginning as solid cellular sprouts from the endothelial cells of persisting vessels that subsequently become canalized. Cell branching and fine cross-striations are clearly visible and indicate the intracellular organization of sarcomeres. Dyad Myofibril Lymphoedema Insufficient lymphatic drainage leads to accumulation of fluid in the tissues (oedema) and swelling, typically in the limbs.

Buy discount flagyl 250 mg on-line

Bone organic matrix includes small amounts of various macromol ecules attached to collagen fibres and surrounding bone crystals infection near eye buy flagyl pills in toronto. The functions of some of these molecules are described with osteoblasts (see below). Osteoblasts Osteoblasts are derived from osteoprogenitor (stem) cells of mesenchy mal origin present in bone marrow and other connective tissues. In relatively quiescent adult bone, they appear to be present mostly on endosteal rather than periosteal surfaces, but they also occur deep within compact bone wherever osteons are being remodelled. Osteoblasts are responsible for the synthesis, deposition and minerali zation of the bone matrix, which they secrete. They contain prominent bundles of actin, myosin and other cytoskeletal proteins associated with the maintenance of cell shape, attachment and motility. Their plasma membranes display many extensions, some of which contact neighbouring osteoblasts and embedded osteocytes at intercellular gap junctions. This arrangement facilitates coordination of the activities of groups of cells. Osteo calcin is required for bone mineralization, binds hydroxyapatite and calcium, and is used as a marker of new bone formation. Osteonectin is a phosphorylated glycoprotein that binds strongly to hydroxyapatite and collagen; it may play a role in initiating crystallization and may be a cell adhesion factor. Large multicellular osteoclasts (white arrow) are actively resorbing bone on one surface, while a layer of osteoblasts (black arrow) is depositing osteoid on another. Osteoblasts that have become trapped in the matrix to form osteocytes are shown in the centre (white arrowhead). Their branching dendrites contact those of neighbouring cells via the canaliculi seen here within the bone matrix. Several other osteocyte lacunae are present, out of the focal plane in this section, and tangential to the osteon axis. The bone sialoproteins, osteopontin and thrombospondin, mediate osteoclast adhesion to bone surfaces by binding to osteoclast integrins. Although extracellular fluid is generally supersaturated with respect to the basic calcium phosphates, mineralization does not occur in most tissues. In bone, osteoblasts secrete osteocalcin (binds calcium at levels sufficient to concentrate the ion locally) and contain membranebound vesicles full of alkaline phosphatase (cleaves phosphate ions from various molecules to elevate concentrations locally) and pyrophos phatase (degrades inhibitory pyrophosphate in the extracellular fluid). The vesicles bud off from the osteoblast surface into newly formed osteoid, where they initiate hydroxyapatite crystal formation. Some alkaline phosphatase reaches the blood circulation, where it can be detected in conditions of rapid bone formation or turnover. Bonelining cells are flattened epitheliallike cells that cover the free surfaces of adult bone not undergoing active deposition or resorption. Generally considered to be quiescent osteoblasts or osteoprogenitor cells, they line the periosteal surface and the vascular canals within osteons, and form the outer boundary of the marrow tissue on the endosteal surface of marrow cavities. Internal resorption of the bone has produced large, irregular dark spaces (trabecularization). The rather narrow rim of cytoplasm is faintly basophilic, contains relatively few organelles and surrounds an oval nucleus. Numerous fine branching processes containing bundles of microfilaments and some smooth endoplasmic reticulum emerge from each cell body. At their distal tips, these processes form gap junctions with the processes of adjacent cells (osteocytes, osteoblasts and bone lining cells) so that they are in electrical and metabolic continuity. Extracellular fluid fills the small, variable spaces between osteocyte cell bodies and their rigid lacunae, which may be lined by a variable (0. The same fluid fills the narrow channels or canaliculi that surround the long processes of the osteocytes. Canaliculi do not usually extend through and beyond the reversal line surrounding each osteon and so do not communicate with neighbouring systems. In wellvascularized bone, osteocytes are longlived cells that actively maintain the bone matrix. The average lifespan of an osteocyte varies with the metabolic activity of the bone and the likelihood that it will be remodelled, but is measured in years. Old osteocytes may retract their processes from the canaliculi; when they die, their lacunae and canaliculi may become plugged with cell debris and minerals, which hinders diffusion through the bone. Dead osteocytes occur com monly in interstitial bone (between osteons) and in central regions of trabecular bone that escape surface remodelling. Their cytoplasm contains numerous mitochondria and vacu oles, many of which are acid phosphatasepositive lysosomes. Rough endoplasmic reticulum is relatively sparse but the Golgi complex is extensive. A welldefined zone of actin filaments and associated proteins occurs beneath the ruffled border around the circumference of a resorption bay, in a region termed the sealing zone. They dissolve bone minerals by proton release to create an acidic local environment, and they remove organic matrix by secreting lysosomal (cathepsin K) and nonlysosomal. Calcitonin, produced by C cells of the thyroid follicle, reduces osteoclast activity. Osteoclasts differentiate from myeloid stem cells via macrophage colonyforming units. Osteoclast differen tiation inhibitors are potential therapeutic agents for bone loss associated disorders. Newly synthesized collagenous osteoid matrix (M) is seen in the centre field, with a mineralization front (electron-dense area) below (arrows). At the borders of lamellae, packing of col lagen fibres into bundles is less perfect and intermediate and random orientations of collagen predominate. Adjacent osteons may encroach on one another because they are usually formed at different times, during suc cessive periods of bone remodelling. The main direction of collagen fibres within osteons varies: in the shaft of long bones, fibres are more longitudinal at sites that are subjected mainly to tension, and more oblique at sites subjected mostly to compression. It has been estimated that there are 21 million osteons in a typical adult skeleton. Each osteon is permeated by the canal iculi of its resident osteocytes, which form pathways for the diffusion of metabolites between osteocytes and blood vessels. Each canal contains one or two capillaries lined by fenestrated endothe lium and surrounded by a basal lamina, which also encloses typical pericytes. The bony surfaces of osteonic canals are perforated by the openings of osteocyte canaliculi and are lined by collagen fibres. Haversian canals communicate with each other and directly or indi rectly with the marrow cavity via vascular (nutrient) channels called Woven and lamellar bone the mechanical properties of bone depend not only on matrix compo sition, as described above, but also on the manner in which the matrix constituents are organized. In woven (or bundle) bone, the collagen fibres and bone crystals are irregularly arranged. The diameters of the fibres vary, so that fine and coarse fibres intermingle, producing the appearance of the warp and weft of a woven fabric. It is formed by highly active osteo blasts during development, and is stimulated in the adult by fracture, growth factors or prostaglandin E2. Lamellar bone, which makes up almost all of an adult skeleton, is more organized and is produced more slowly. In trabeculae and the outer (periosteal) and inner (endosteal) surfaces of cortical bone, a few lamellae form continuous circumferential layers that are more or less parallel to the bony surfaces.

Purchase flagyl 400mg with visa