Buy 250 mg ritonavir free shipping

While there are reports of hearing preservation with either total or partial tumor resection via the retrosigmoid route treatment zenker diverticulum cheap ritonavir 250mg on-line, it is our experience that this goal is rarely, if ever, accomplished, at least with larger tumors or in cases of more severe disease. Promises of "tumor debulking with hearing preservation" should be viewed with suspicion. Similar to patients with sporadic tumors, maintenance of useful hearing can be achieved in a significant portion of patients with an otherwise low complication rate. In most cases, this limits the option of early surgical intervention to "first side" treatment in those who retain good hearing bilaterally. The choice of early surgical intervention should be offered only to patients with proven growing tumors with favorable imaging characteristics. Fundal tumor impaction, as well as involvement of the cochlea or vestibule, precludes successful hearing preservation in most cases. Lack of abnormal enhancement along the course of the facial nerve in the temporal bone does not, however, preclude the possibility of encountering a facial nerve tumor intraoperatively. Microsurgery for Neurofibromatosis Type 2 Focusing on Vestibular Schwannoma number of patients will choose this option rather than continuing to wait until tumors grow too large to consider any attempt at hearing preservation surgery. While long-term hearing prognosis is thought to be improved in patients who have had hearing preserved after proactive surgery, follow-up studies have shown that new or recurrent tumors develop in a significant percentage of cases. Of course, middle fossa decompression is a palliative measure that does not affect tumor growth and may indeed make further interventions more complicated. The combination of middle fossa decompression and bevacizumab or other novel therapies may hold promise in preserving function. Evidence of polyclonality in neurofibromatosis type 2-associated multilobulated vestibular schwannomas. Neurofibromatosis 2 leads to higher incidence of strabismological and neuro-ophthalmological disorders. Surgical management of vestibular schwannomas and hearing rehabilitation in neurofibromatosis type 2. Microsurgery management of vestibular schwannomas in neurofibromatosis type 2: indications and results. Hearing preservation with the middle cranial fossa approach for neurofibromatosis type 2. Middle fossa decompression for hearing preservation: a review of institutional results and indications. In the initial series, only about 5% of patients were capable of significant open-set speech discrimination. Possible factors for improved performance include choice of approach, positioning, choice of device, and nuances of surgical technique. Outcome of translabyrinthine surgery for vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2. Strategy for the surgical treatment of vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. One retrospective report from the Mayo Clinic examined the effect of dose on tumor response, taking into account that their institution continued to use a margin dose of 14 Gy until 1996. Current functional outcomes should be superior with advanced radiosurgery techniques,23 as with other tumor types. Based on the analysis of Seferis et al,33 the reported overall risk of malignant transformation after radiation treatment over 20 years is 25. A limitation with many of these studies is that there lacks histology to confirm a previously benign lesion. Diagnosis, management, and new therapeutic options in childhood neurofibromatosis type 2 and related forms. Long-term natural history of neurofibromatosis Type 2-associated intracranial tumors. Spontaneous regression of vestibular schwannomas after resection of contralateral tumor in neurofibromatosis Type 2. Concordance of bilateral vestibular schwannoma growth and hearing changes in neurofibromatosis 2: 82. Of the studies that reported on malignant transformation in Table 1, none were observed. In a population study of nearly 5,000 cases from Sheffield, England, there was no increased rate of malignancy of any kind after radiosurgery. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: an analysis of tumor control, complications, and hearing preservation rates. Stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of acoustic neuromas associated with neurofibromatosis Type 2. Clinical experience with gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery in the management of vestibular schwannomas secondary to type 2 neurofibromatosis. Radiosurgical treatment of vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: tumor control and hearing preservation. Tumor control and hearing preservation after Gamma Knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas in neurofibromatosis type 2. Long-term follow-up studies of Gamma Knife surgery for patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. Safety of radiosurgery applied to conditions with abnormal tumor suppressor genes. Linear acceleratorbased stereotactic radiosurgery for bilateral vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for meningiomas in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. Current strategies target the abnormal merlin-controlled growth regulator pathways through blockade of surface receptors or intracellular signaling pathways, and/or target the tumors microenvironment (endothelial cells) by inhibiting neoangiogenesis. Multiple proneoplastic pathways are activated in merlin-deficient cells and significant "cross-talk" exists, leading to treatment failure or development of drug resistance. Small-molecule inhibitors (those ending in "-inib") are novel in that they are able to cross the cell membrane to affect the intracellular domain of cell-surface receptors and also block the activation of various downstream signaling pathways intracellularly; while this potentially increases their breadth of inhibition, it may also lead to more "off-target" adverse side effects. To date, several preclinical and clinical studies have made progress toward these goals. Currently, the major benchmarks to evaluate drug efficacy include (1) hearing outcomes as measured by speech discrimination (word recognition) scores and (2) radiographic outcomes based on changes in tumor volume. Moreover, these results were inferior to those obtained in the retrospective series of patients treated with bevacizumab, where a 70% of patients achieved a volumetric response (when defined as 15% volume reduction) and 57. In addition, patients treated with lapatinib did not show regression of coexisting meningiomas, as these tumors continued to progress with many of the patients during the study. These epigenetic modifications in gene expression result in upregulation of proapoptotic genes and downregulation of survival genes, which effectively lowers the apoptotic threshold of tumor cells. Advances in bioinformatics are leading to a better understanding of the functional relationships between differentially expressed genes and the molecular players of dysregulated pathways. High-throughput screening of compound libraries with phenotypic assays is serving as an efficient, nonbiased, empirical technique for researchers to quickly conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests to aid in the drug discovery and target identification process. With the development of increasingly novel molecular-targeted therapies, a surge of preclinical and clinical trials is sure to follow in the coming years ahead. Immunohistochemical demonstration of vascular endothelial growth factor in vestibular schwannomas correlates to tumor growth rate. Bevacizumab for progressive vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Bevacizumab induces regression of vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Efficacy and biomarker study of bevacizumab for hearing loss resulting from neurofibromatosis type 2-associated vestibular schwannomas. The ErbB inhibitors trastuzumab and erlotinib inhibit growth of vestibular schwannoma xenografts in nude mice: a preliminary study. Aspirin intake correlates with halted growth of sporadic vestibular schwannoma in vivo. Nilotinib alone or in combination with selumetinib is a drug candidate for neurofibromatosis type 2. Dissecting and targeting the growth factor-dependent and growth factor-independent extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in human schwannoma.

Trusted ritonavir 250mg

In addition 72210 treatment ritonavir 250 mg overnight delivery, many clinicians recommend the use of isobaric solutions to reduce the risk of nonuniform distribution within the intrathecal space. Attention to patient positioning, total local anesthetic dose, and careful neurologic examination (evaluating for preferential sacral block) will assist in the decision to inject additional local anesthetic in the face of a patchy or failed block (31) (Tables 12-3 and 12-4). In all cases, the injury occurred after a large volume of anesthetic solution intended for the epidural space was accidentally administered intrathecally. Subsequent laboratory investigations evaluating the toxic contributions of 2-chloroprocaine, bisulfite, epinephrine, and pH reported that the commercial solution of 3% chloroprocaine (containing 0. If maldistribution is suspected, use maneuvers to increase the spread of local anesthetic. If well-distributed sensory anesthesia is not achieved before the dose limit is reached, abandon the technique. Local anesthetic neurotoxicity: Clinical injury and strategies that may minimize risk. Schneider and colleagues (3) reported four cases of severe radicular back pain occurring after resolution of hyperbaric lidocaine spinal anesthesia. No sensory or motor deficits were detected on examination, and the symptoms resolved spontaneously within several days. In addition, the incidence was higher among patients positioned with knees or hips flexed (genitourinary, arthroscopy) than in patients positioned supine (herniorrhaphy), presumably because the flexion results in additional stretch on the nerve roots. The pain was described as severe in 30% of patients and resolved within a week in over 90% of cases. There was no evidence of neurologic deficits; in all patients, the symptoms disappeared spontaneously by the 10th postoperative day. More recently, these experiments were repeated with a more appropriate animal model and yielded different results: nerve injury scores were greater after administration of plain chloroprocaine compared to those of chloroprocaine containing bisulfite. These findings suggest clinical deficits associated with unintentional intrathecal injection of chloroprocaine likely resulted from a direct effect of the anesthetic, not the preservative. In addition, the data suggest that bisulfite can actually reduce neurotoxic damage induced by intrathecal local anesthetic (33). Sacral dermatomes should always be included in an evaluation of the presence of a spinal block. If an injection is repeated, the technique should be modified to avoid reinforcing the same restricted distribution. Therefore, the clinician must determine the appropriate intrathecal solution, including adjuvants, given the surgical duration and intraoperative position for each individual patient. Systemic hypotension or localized vascular insufficiency with or without a spinal anesthetic may produce spinal cord ischemia resulting in flaccid paralysis of the lower extremities (including sphincter dysfunction) or anterior spinal artery syndrome (44). Classically, proprioception and sensation are spared or preserved, relative to motor loss. Characteristics of anterior spinal artery syndrome, spinal abscess, and spinal hematoma are reported in (45) (Table 12-6). However, in laboratory investigations, the alterations in blood flow are not accompanied by changes in histology or behavior. Likewise, large clinical studies have failed to identify the use of vasoconstrictors as a risk factor for temporary or permanent deficits. Most presumed cases of vasoconstrictorinduced neurologic deficits have been reported as single case reports, often with several other risk factors present (2,49). Finally, the addition of vasoconstrictors may potentiate the neurotoxic effects of local anesthetics. In a laboratory model, it was determined that the neurotoxicity of intrathecally administered lidocaine was increased by the addition of epinephrine (50). The intrathecal administration of 2-chloroprocaine is under reconsideration due to the concern regarding toxicity, as previously mentioned. Recent studies suggest a local anesthetic toxicity, although the mechanism may not be identical to that of cauda equina syndrome (43). Although many anesthesiologists believe that the reversible radicular pain is on one side of a continuum leading to irreversible cauda equina syndrome, no data support this concept. It is important to distinguish between factors associated with serious neurologic complications, such as cauda equina syndrome, and transient symptoms when making recommendations for the clinical management of patients. Chapter 12: Neurologic Complications of Neuraxial Block 301 containing vasoconstrictors appears to be very low. Clinicians should be aware of other surgical and patient factors predisposing to spinal cord ischemia, including major aortic vascular or spinal column procedures, arthrosclerosis, sustained hypotension, and anemia. Although neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia reduce the risk of venous thrombosis, a significant risk remains, even in the presence of a continuous epidural infusion containing a local anesthetic (53). The risk factors for thromboembolism include trauma, immobility/paresis, malignancy, previous thromboembolism, increasing age (over 40 years), pregnancy, estrogen therapy, obesity, smoking history, varicose veins, and inherited or congenital thrombophilia. Not surprisingly, only the healthiest patients undergoing minor surgery are not considered candidates for thromboprophylaxis postoperatively. Guidelines for antithrombotic therapy including appropriate pharmacologic agent, degree of anticoagulation desired, and duration of therapy continue to evolve. There is a trend toward initiating thromboprophylaxis in close proximity to surgery. Likewise, the duration of prophylaxis has been extended to a minimum of 10 days following total joint replacement or hip fracture surgery, whereas the recommended duration for hip procedures is 28 to 35 days. It has been demonstrated that the risk of bleeding complications is increased with the duration of anticoagulant therapy. The interaction of prolonged thromboprophylaxis and previous neuraxial instrumentation, including difficult or traumatic needle insertion, is unknown. Clinical outcomes, such as fatal pulmonary embolism and symptomatic deep venous thrombosis are not primary endpoints. Despite the successful reduction of asymptomatic thromboembolic events with routine use of antithrombotic therapy, an actual reduction of clinically relevant events has been more difficult to demonstrate. In a review of the literature between 1906 and 1994, Vandermeulen and colleagues (52) reported 61 cases of spinal hematoma associated with epidural or spinal anesthesia. In 87% of patients, a hemostatic abnormality or traumatic/difficult needle placement was present. Importantly, although only 38% of patients had partial or good neurologic recovery, spinal cord ischemia tended to be reversible in patients who underwent laminectomy within 8 hours of onset of neurologic dysfunction. Importantly, the presence of postoperative numbness or weakness was typically attributed to local anesthetic effect rather than spinal cord ischemia, which delayed the diagnosis. Patient care was rarely judged to have met standards (1 of 13 cases), and the median payment was very high. It is impossible to conclusively determine risk factors for the development of spinal hematoma in patients undergoing neuraxial blockade solely through review of the case series, which represent only patients with the complication and do not define those who underwent uneventful neuraxial analgesia. However, large inclusive surveys that evaluate the frequencies of complications (including spinal hematoma), as well as identify subgroups of patients with higher or lower risk, enhance risk stratification. In the series by Moen and co-workers (8) involving nearly 2 million neuraxial blocks, 33 spinal hematomas occurred. The methodology allowed for the calculation of frequency of spinal hematoma among patient populations. For example, the risk associated with epidural analgesia in women undergoing childbirth was significantly less (one in 200,000) than that in elderly women undergoing knee arthroplasty (one in 3,600, p <0. Likewise, women undergoing hip fracture surgery under spinal anesthesia had an increased risk of spinal hematoma (one in 22,000) compared to all patients undergoing spinal anesthesia (one in 480,000). They also consistently demonstrate the need for prompt diagnosis and intervention. Neuraxial Anesthesia and Anticoagulation Practice guidelines or recommendations summarize evidencebased reviews. However, the rarity of spinal hematoma defies a prospective-randomized study, and no current laboratory model exist. As a result, the consensus statements developed by the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine represent the collective experience of recognized experts in the field of neuraxial anesthesia and anticoagulation. They are based on case reports, clinical series, pharmacology, hematology, and risk factors for surgical bleeding. An understanding of the complexity of this issue is essential to patient management.

Order ritonavir 250 mg mastercard

Such procedures include major abdominal vascular surgery (64) medications memory loss buy ritonavir, transcutaneous hepatic biliary drainage (65), thoracoabdominal esophagectomy (66), and inguinal hernior- Nonsurgical Applications When the block is used for diagnostic purposes, only small volumes of local anesthetic solution should be injected, so as to limit spread centrally or to adjacent lumbar nerves. Some physicians use fluoroscopy or a nerve stimulator to position the needle precisely and then inject only 0. Complications It is possible to inject into intravascular, epidural, or subarachnoid spaces during performance of this block. Should the needle be inserted too far medially, it could enter a vertebral foramen or penetrate a dural sleeve to produce spinal anesthesia. Perineural spread of solution into the epidural space may also occur, with a consequent variable degree of anesthesia over the lower extremities. Intravascular injection can be minimized by aspiration tests, and by avoiding large-volume injections. Intraperitoneal injection, or puncture of retroperitoneal (kidney) or intra-abdominal organs, is possible. These nerves enter the rectus sheath at the posterolateral border of the body of that muscle. The tendinous intersections of the rectus tend to create segmental distributions of individual intercostal nerves, but some overlap of adjacent fibers occurs. Posteriorly, it is strong and readily identifiable down to the level of the umbilicus, but then it fades into a thin sheath of transversalis fascia, which adheres closely to the peritoneum below the semicircular line of Douglas. The posterior rectus sheath above the umbilicus is quite substantial and can serve as a "backboard" for injecting local anesthetic solution. This solution will be confined by the tendinous intersections, but within those limits will spread up and down to anesthetize the peripheral motor and sensory branches of the intercostal nerves. These are delineated by a vertical line through umbilicus and horizontal lines at umbilical level, and midway between umbilicus and xiphisternum, and umbilicus and pubis, respectively. C: Needle penetrates rectus muscle and is halted by resistance of posterior rectus sheath. Note the latter structure is absent below the line midway between umbilicus and pubis. Sonoanatomy of Rectus Sheath Block Technique the patient lies supine, and the anesthesiologist may stand at either side. If performed while the patient is awake, skin wheals are raised at the middle of each segment of the rectus muscle body that can be palpated between tendinous intersections. A reusable or short-bevel 5-cm, 22-gauge needle is passed through skin and subcutaneous tissue until it meets the firm resistance of the anterior rectus sheath. The block should be discontinued unless this sheath can be convincingly demonstrated upon advancing the needle. With controlled, steady pressure, the needle is pushed to penetrate this sheath with a definite snap. Advancing further passes the needle through the softer belly of the muscle, and as the needle approaches the posterior rectus sheath, the anesthesiologist will feel firm resistance again. Using this posterior sheath as a backboard, 10 mL of local anesthetic solution is injected. Willschke and colleagues (69) have described the performance of ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block in children undergoing umbilical hernia repair. The use of ultrasound may help the anesthesiologist decrease the incidence of complications and improve the success rate of the block. Ultrasound-guided Rectus Sheath Block Technique Using ultrasonic guidance, the target is kept in the center of the field of view, and the needle entry site is at the lateral-most end of the linear transducer. Nonsurgical Applications Rectus block may be useful in diagnosing abdominal nerve entrapment syndromes or localized myofascial problems. Surgical Applications the rectus sheath block can provide good intra- and postoperative analgesia for abdominal surgery requiring a midline incision. The block has proven useful in the management of surgical pain after incisional and umbilical hernia repair, postpartum and laparoscopic tubal ligation, cesarean section when a midline incision is used (70), and outpatient laparoscopy (71). It is widely used for pediatric patients, particularly in the ambulatory surgical setting. Complications It is difficult to identify the posterior rectus sheath where it lies near the xiphoid and pubis. Attempting this block at these levels may result in penetration of peritoneum and underlying organs such as liver, intestine, bladder, or uterus. In the patient with a distended abdomen, the thinly stretched rectus may prevent clear identification of anterior and posterior sheaths. A visible bulge in the abdominal wall upon injection indicates that the needle is too superficial, and a poor block will result. The block is more difficult in the obese, cachectic, or elderly patient with poor abdominal muscle tone. The procedure is repeated on either side of the midline, as blockade of the contralateral sensory afferents is necessary to obtain midline analgesia. At or near the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, the twelfth thoracic and iliohypogastric nerves lie between the internal and external oblique muscles. These three nerves continue anteromedially and become superficial as they terminate in branches to skin and muscles of the inguinal region. Ultrasound transducer and needle positioning during ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block. As already reported, the use of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve blocks is popular, yet clinical experience with this technique indicates block failure rates of 10% to 25% (72). Willschke and co-workers (73) have reported that the use of ultrasound in locating the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves yields a higher success rate than the classic landmark technique. Four percent of patients in the ultrasound group required supplemental intraoperative analgesia compared to 26% in the landmark group. They also reported a significant reduction in the volume of anesthetic agent required for successful block in the ultrasound group. Thus, ultrasonic guidance would appear to improve the quality and success rate of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block when compared to traditional landmark techniques. Visualization of the needle, nerve, and peritoneum should help prevent nerve injury and also visceral injury associated with traditional, blind techniques. Ultrasound appearance of anesthetic solution injected into the posterior rectus sheath. Using the anterior superior iliac spine as a primary point of orientation, the anesthesiologist can block these nerves. Success depends on spreading a large volume of anesthetic solution between abdominal wall muscle layers. The block is inadequate to provide total anesthesia for inguinal herniorrhaphy, because structures that enter the inguinal canal through the internal inguinal ring will not be anesthetized, but the surgeon can block the latter adequately with direct local infiltration of the spermatic cord during the procedure. A 23-gauge needle is advanced under real-time ultrasonic guidance, and local anesthetic is deposited along the needle entry path. The needle is attached to sterile extension tubing, which is connected to a 20-mL syringe and preflushed with local anesthetic solution to clear all air from the system. It is important not to advance the needle without good visualization, which may require transducer adjustment. Technique the procedure can be performed with the patient lying in the supine position, awake or anesthetized. The skin puncture point is 1 cm medial and 1 cm inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine. A characteristic "click" may be felt on penetrating the external oblique, at which point 6 to 8 mL of local anaesthetic is injected, following aspiration, in increments of 2. Advancing the needle further will result in a second characteristic "click" as the needle penetrates the internal oblique. A further 6 to 8 mL is injected at this point (with the usual precautions) to anesthetize the ilioinguinal nerve. A similar subcutaneous injection can be made toward the midline to block other branches of the subcostal nerve. If herniorrhaphy is to be performed, a second skin wheal may be raised 2 to 3 cm above the midinguinal point. Infiltration of 10 to 15 mL of local anesthetic solution in fan-wise fashion will anesthetize the genitofemoral nerve, sympathetic fibers, and peritoneal sac. Thus, it may be preferable for the surgeon to inject 2 to 3 mL of local anesthetic circumferentially into the spermatic cord as soon as it is exposed. Surgical Applications Ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks can provide adequate anesthesia for field block for groin surgery (in combination with genitofemoral nerve block/surgical infiltration at deep and superficial inguinal rings) and postoperative analgesia.

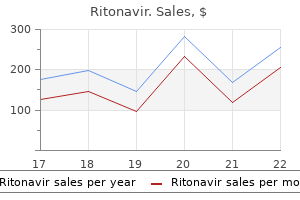

| Comparative prices of Ritonavir | ||

| # | Retailer | Average price |

| 1 | Dillard's | 627 |

| 2 | Kroger | 447 |

| 3 | Foot Locker | 367 |

| 4 | Tractor Supply Co. | 111 |

| 5 | AutoZone | 841 |

| 6 | Bon-Ton Stores | 197 |

| 7 | Macy's | 562 |

| 8 | Bed Bath & Beyond | 640 |

| 9 | Safeway | 705 |

Ritonavir 250 mg cheap

Changes in expression of two tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels and their currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons after sciatic nerve injury but not rhizotomy treatment 1st 2nd degree burns cheap ritonavir 250mg on-line. Changes in the expression of tetrodotoxinsensitive sodium channels within dorsal root ganglia neurons in inflammatory pain. Sodium channel 2 subunits regulate tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels in small dorsal root ganglion neurons and modulate the response to pain. Upregulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel 2 subunit in neuropathic pain models: Characterization of expression in injured and non-injured primary sensory neurons. Intrinsic lidocaine affinity for Na channels expressed in xenopus oocytes depends on alpha (hH1 vs. Distinct domains of the sodium channel beta3-subunit modulate channel-gating kinetics and subcellular location. Time dependent block and resurgent tail currents induced by mouse 4154-167 peptide in cardiac Na+ channels. Tetrodotoxin-resistant action potentials in dorsal root ganglion neurons are blocked by local anesthetics. Stereoisomerism and differential activity in excitation block by local anesthetics. Stereoselective inhibition of neuronal sodium channels by local anesthetics: Evidence for two sites of action Point mutations at N434 in D1-S6 of 1 Na+ channels modulate binding affinity and stereoselectivity of local anesthetic enantiomers. Topical Review: Interactions of local anesthetics with voltage-gated Na+ channels. Cocaine-induced closures of single batrachotoxin-activated Na+ channels in planar lipid bilayers. Differences in steady-state inactivation between Na channel isoforms affect local anesthetic binding affinity. Differential properties of tetrodotoxin-sensitive and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Determination of the full dose-response relation of intrathecal bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine, combined with sufentanil, for labor analgesia. Characteristics of ropivacaine block of Na+ channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Local anesthetic inhibition of G protein-coupled receptor signaling by interference with Galpha(q) protein function. Some properties of inhibitory action of lidocaine on the Ca2+ current of single isolated frog sensory neurons. Slow calcium and potassium currents in frog skeletal muscle: their relationship and pharmacological properties. Somatosensory, proprioceptive and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. The critical role of concentration for lidocaine block of peripheral nerve in vivo. The effects of epinephrine on the anesthetic and hemodynamic properties of ropivacaine and bupivacaine after epidural administration in the dog. Subanesthetic concentrations of lidocaine selectively inhibit a nociceptive response in the isolated rat spinal cord. Changes of response pattern of sensory afferent in rats exposed to sub-blocking concentrations of lidocaine. The effects of 4-amino pyridine and tetraethylammonium ions on normal and demyelinated mammalian nerve fibres. Susceptibility to lidocaine of impulses in different somatosensory afferent fibers of rat sciatic nerve. Differential peripheral axon block with lidocaine: Unit Studies in the cervical vagus nerve. Differential slowing and block of conduction by lidocaine in individual afferent myelinated and unmyelinated axons. Preferential block of small myelinated sensory and motor fibers by lidocaine: In vivo electrophysiology in the rat sciatic nerve. Onset, intensity of blockade and somatosensory evoked potential changes of the lumbosacral dermatomes after epidural anesthesia with alkanized lidocaine. Physical and chemical properties of drug molecules governing their diffusion through the spinal meninges. Pharmacokinetic nature of tachyphylaxis to lidocaine in peripheral nerve blocks and infiltration anesthesia in rats. Local anesthetics drugs: Penetration from the spinal extradural space into the neuraxis. Sites of sensory blockade during segmental spinal and segmental peridural anesthesia in man. Clinical observations suggesting a changing site of action during induction and recession of spinal and epidural anesthesia. Local anesthetic inhibition of voltage-activated potassium currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Blockade of Na+ and K+ currents by local anesthetics in the dorsal horn neurons of the spina cord. A trial of intravenous lidocaine on the pain and allodynia of postherpetic neuralgia. Time-dependent descending facilitation from the rostral ventromedial medulla maintains, but does not initiate, neuropathic pain. Differential blockade of nerve injury-induced thermal and tactile hypersensitivity by systemically administered brain-penetrating and peripherally restricted local anesthetics. Multiple phases of relief from experimental mechanical allodynia by systemic lidocaine: Responses to early and late infusions. Prolonged alleviation of tactile allodynia by intravenous lidocaine in neuropathic rats. The analgesic response to intravenous lidocaine in the treatment of neuropathic pain. How strong is the evidence for the efficacies of different drug treatments for neuropathic pain Efficacy and safety of mexiletine in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. Effect of oral mexiletine on capsaicin-induced allodynia and hyperalgesia: a double-blind, placebocontrolled crossover study. Intravenous lidocaine infusion-a new treatment of chronic painful diabetic neuropathy. Perioperative intravenous lidocaine has preventive effects on postoperative pain and morphine consumption after major abdominal surgery. Administration of local anesthetics to relieve neuropathic pain: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Response to intravenous lidocaine infusion predicts subsequent response to oral mexiletine: a prospective study. The cardiovascular effects of convulsant doses of lidocaine and bupivacaine in the conscious dog. Bupivacaine and lidocaine blockade of calcium mediated slow action potentials in guinea pig ventricular muscle. Neurotoxicity of lidocaine involves specific activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, but not ex- 170. Bupivacaine cardiovascular toxicity: Comparison of treatment with bretylium and lidocaine. Hydrophobic and ionic factors in the binding of local anesthetics to the major variant of human 1 -acid glycoprotein. Pretreatment or resuscitation with a lipid infusion shifts the dose-response to bupivacaine-induced asystole in rats. Lipid infusion accelerates removal of bupivacaine and recovery from bupivacaine toxicity in the isolated heart. Transient neurologic toxicity after hyperbaric subarachnoid anesthesia with 5% lidocaine. Concentration dependence of lidocaine-induced irreversible conduction loss in frog nerve.

Cheap ritonavir 250mg overnight delivery

Postoperative infusion of amino acids induces a positive protein balance independently of the type of analgesia used medicine ball slams purchase ritonavir canada. Accelerated postoperative recovery programme after colonic resection improves physical performance, pulmonary function and body composition. Epidural analgesia enhances functional exercise capacity and health-related quality of life. Metabolic control of non-insulin dependent diabetic patients undergoing cataract surgery: Comparison of local and general anesthesia. Comparison of analgesic methods for total knee arthroplasty: Metabolic effect of exogenous glucose. Epidural analgesia enhances the postoperative anabolic effect of amino acids in diabetes mellitus type 2 patients undergoing colon surgery. Effect of laparoscopic colon resection on postoperative glucose utilization and the protein sparing effect. Thoracic epidural analgesia facilitates the restoration of bowel function and dietary intake in patients undergoing laparoscopic colon resection with a traditional, non-accelerated, perioperative care program. Intravenous lidocaine infusion facilitates acute rehabilitation after laparoscopic colectomy. The presence of uncontrolled acute pain may potentially result in widespread adverse responses that may contribute to a number of perioperative complications. Schricker and Carli, the effective management of acute pain may attenuate several of these adverse responses and, in turn, improve patient outcomes. Many different classes of analgesic agents and different analgesic techniques exist, each of which has a unique profile. However, regional anesthesia and analgesic techniques, including neuraxial and peripheral regional analgesia, are especially effective in the provision of postoperative analgesia and attenuation of perioperative pathophysiology. In this article, we review the evidence, focusing on available systematic review and meta-analyses, for the effects of regional anesthetic and analgesia techniques (both peripheral and neuraxial) on patient outcomes. Clinicians should recognize that the neurobiology of nociception is extremely complex, with multiple levels of redundancy such that no "hardwired" or "final common" pathway exists for the process of nociception. Comprehensive discussions of the neuroanatomy and pharmacology of nociception are provided in Chapters 31 through 33. For the purposes of the present chapter, we will concisely survey these processes and limit our description of central nociceptive processing to that taking place in the spinal cord. Primary afferent nociceptors, which are distinct from those that carry innocuous somatic sensory information, convert a wide range of environmental noxious stimuli into electrochemical signals. The electrochemical signals processed by the primary afferent nociceptors are transmitted toward the spinal cord in the small diameter A- and C-fibers that primarily transmit nociceptive information. Primary sensory afferent nociceptors synapse with neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neurotransmission across the synapse, originating from peripheral afferent A- and Cfibers, is mediated by a number of peptides and amino acids that interact with specific receptors postsynaptically. Central (Spinal) Nociceptive Processing and Descending Modulation Although the primary afferents release neurotransmitters to activate the second-order neurons in the spinal cord, the specific actions depend on the particular receptor activated, since the second-order neurons in the dorsal horn contain a wide variety of neurotransmitter receptors. Actual transmission of nociceptive information may also be modified by descending inhibitory systems including serotonin, enkephalin, and noradrenergic neurons (see Chapters 31 and 32). Although not all nociceptive input results in a pathologic process, a certain percentage of patients who undergo surgical procedures will exhibit prolonged central sensitization and chronic pain. Pathologic nociceptive input may cause a central sensitization that is marked by hyperexcitable spinal neurons that exhibit a decreased threshold for activation, increased and prolonged response to noxious input, expansion of receptive fields, possible spontaneous activity, and activation by normally non-noxious stimuli (33). Ultimately, transcriptional changes (including induction of genes), structural changes in synaptic connections. However, over the subsequent postoperative days, a prolonged phase of postoperative ileus occurs. The presumed etiology of the latter is distinct, and involves an enteric molecular inflammatory response that impairs local neuromuscular function and activates neurogenic inhibitory pathways (10). Our understanding of the mechanisms of postoperative ileus is not complete, and it is likely that these three mechanisms are not discrete phenomena but interrelated (10). Effects on Individual Organ Systems the noxious stimuli and resultant pathophysiology associated with surgery may affect many organ systems and result in postoperative complications, particularly in patients in certain subgroups. Cardiovascular It has traditionally been thought that an imbalance of myocardial oxygen supply and demand, such as an increase in demand. Although many factors may contribute to an imbalance of myocardial oxygen supply and demand, uncontrolled postoperative pain may be especially detrimental and contribute to cardiac morbidity through activation of the sympathetic nervous system, other surgical stress responses, and the coagulation cascade. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity can increase myocardial oxygen demand by increasing heart rate, blood pressure, and contractility or even decrease myocardial oxygen supply, which in turn may lead to angina, dysrhythmias, and areas of myocardial infarction (5). In addition, sympathetic activation may enhance perioperative hypercoagulability, which may contribute to perioperative coronary thrombosis or vasospasm, thus reducing myocardial oxygen supply (7,8). Coagulation It is recognized that hypercoagulability occurs in association with surgical procedures. Nevertheless, the primary components of the coagulation systems comprise cellular. The normal process of coagulation involves several steps including initiation (damaged vascular endothelium expresses tissue factor, which ultimately leads to generation of thrombin), amplification (augmentation of the effects of thrombin), propagation (formation of clot), and stabilization (formation of a stable fibrin meshwork that protects the clot from fibrinolytic attack) (12). However, following surgery, the normal process of coagulation may become unbalanced, which may result in a tendency toward thrombosis. Immediately after surgical incision, there are increases in levels of tissue factor, tissue plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator Pulmonary the pathophysiology of pulmonary dysfunction after surgery is multifactorial. Although the pathophysiology of breathing and respiratory muscle function following surgery is complex, it is clear that anesthetic or analgesic agents administered in the perioperative period affect the central regulation of breathing and activities of respiratory muscles. This incoordination of respiratory muscle function (which may last well into the postoperative period) will impair lung mechanics (9), increasing the risk of hypoventilation, atelectasis, and pneumonia. Visceral stimulation may decrease phrenic motoneuron output, which results in a decrease in diaphragmatic descent and lung volumes (9). A subsequent meta-analysis (20) indicated that the 30-day mortality after mixed orthopedic procedures was significantly lower with use of neuraxial anesthesia (versus general anesthesia) although many methodologic issues are present when interpreting the evidence. Large-scale observational data also suggest that postoperative epidural analgesia may be associated with a significantly lower odds of death (23). A 5% random sample of the Medicare claims database from 1997 through 2001 was analyzed. Patients undergoing a variety of surgical procedures (colectomy, esophagectomy, gastrectomy, hysterectomy, liver resection, nephrectomy, pulmonary resection, radical retropubic prostatectomy, and total knee replacement) were stratified according to the presence (n = 12,780 subjects) or absence (n = 55,943) of a bill for postoperative epidural analgesia. Not unexpectedly, there was a significantly lower mortality in patients who received postoperative epidural analgesia for higher-risk procedures. In addition, an excessive amount or enhanced transmission of serotonin, which is important for mediating mood, sleep, and cognition, can result in confusion and restlessness (15). Immunologic Function It is clear that patients experience an alteration in immune status following surgery. This hyperinflammatory response is followed by significant cell-mediated immunosuppression marked by monocyte deactivation, decreased microbicidal activity of phagocytes, and an overall imbalance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and immunocompetent cells (17,18). Cytokines released into the peritoneal fluid during abdominal surgery may decrease organ function and increase the risk of anastomotic leakage, particularly during sepsis (18). The resultant immunosuppression may lead to an increased risk of postoperative infection and could in theory influence outcomes in oncologic patients. However, it is possible that laparoscopic surgery, which results in less trauma than conventional open surgery, might be associated with a reduced inflammatory response and subsequent immunosuppression due to a decrease in the production of cytokines and in activation of cellular and humoral immune responses (18). Given that 8 million of the 27 million patients in the United States who have surgery every year have coronary artery disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease, cardiac-related events are one of the most common causes of perioperative mortality (24). Within the United States alone, 1 million patients annually have perioperative cardiac complications (at an estimated cost of $20 billion) (25) and worldwide, approximately 5% of the surgical population will develop some type of perioperative cardiac complication (26). Pooled estimate of randomized controlled trials indicating that use of perioperative neuraxial anesthesia (compared to general anesthesia) is associated with a significantly lower odds (30%) of 30-day mortality after a variety of surgical procedures. Thoracic epidural analgesia may increase the diameter of stenotic epicardial coronary arteries in patients with coronary artery disease without changing the diameter of nonstenotic segments, and it does not induce any changes in coronary perfusion pressure, total myocardial blood flow, coronary venous oxygen content, or regional myocardial oxygen consumption (27). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses examine the effects of neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia on cardiovascu- lar events.

Buy generic ritonavir 250 mg line

Although intrathecal local anesthetics treatment 1st degree av block purchase ritonavir 250 mg on-line, but not opioids, may induce perioperative thoracic cardiac sympathectomy, the hemodynamic changes (hypotension) associated with this technique makes it unpalatable in patients with cardiac disease. Epidural techniques with opioids and/or local anesthetics also initiate reliable intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. Administration of thoracic epidural local anesthetics (not opioids) can reliably attenuate the perioperative stress response as well as induce perioperative thoracic cardiac sympathectomy. The ultimate decision regarding anesthetic technique should be made only after thoughtfully considering many factors. One must keep in mind that morbidity and mortality following abdominal aortic reconstruction is likely influenced most by maintenance of perioperative hemodynamic stability. This may be safely achieved in many ways (with or without associated neural blockade). Intrathecal techniques, as applied to patients undergoing abdominal aortic reconstruction, are primarily limited to use of intrathecal morphine for postoperative analgesia. Use of more lipophilic opioids, such as fentanyl, would only provide shortterm analgesia and would not be appropriate for these long surgeries. Use of intrathecal local anesthetics would provide analgesia for a longer period of time, yet the induced sympathectomy is undesirable in these patients, especially during hemodynamic changes associated with aortic clamping and unclamping. A wide variety of epidural techniques (local anesthetics and/or opioids) without (157,158) or (more commonly) with general anesthesia may be used. Most clinicians use a mixture of epidural local anesthetic and opioid throughout the intraoperative period (along with general anesthesia) and well into the immediate postoperative period following tracheal extubation (159,160). Thus, a wide variety of intrathecal and/or epidural techniques may be safely used in patients undergoing abdominal aortic reconstruction. Although regional anesthesia may be used alone, most clinicians use these techniques to supplement general anesthesia. An enormous amount of possibilities exist that allow one to achieve desired perioperative goals safely and efficaciously. Lower Extremity Revascularization A wide variety of anesthetic techniques and drugs may be used safely in patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization. Because the required surgical incisions are smaller and more peripheral than those used during thoracoabdominal and abdominal Abdominal Aortic Reconstruction A wide variety of anesthetic techniques and drugs may be used safely in patients undergoing abdominal aortic reconstruction. Despite this, the vast majority of neural blockade techniques for patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization involve intrathecal and/or epidural techniques (164). Although most anesthesiologists supplement a general anesthetic, a fair amount of lower extremity revascularizations can be performed solely under intrathecal and/or epidural techniques, in contrast to thoracoabdominal and abdominal aortic reconstruction. Selection of technique is similar to considerations for patients undergoing aortic reconstruction: intrathecal/epidural route and administration of local anesthetic/opioid and the associated changes in the stress response and hemodynamics. This may be safely achieved many ways, with or without associated neural blockade. Outcome Two early clinical studies indicated that use of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in patients following noncardiac surgery may beneficially affect outcome (7,8). In 1987, Yeager and associates, in a small (n = 53 patients), randomized, controlled clinical trial involving patients undergoing major thoracic/vascular surgery, revealed that patients who were managed to receive epidural anesthesia and analgesia demonstrated decreased postoperative morbidity and improved operative outcome (8). Furthermore, studies assessing outcome cannot determine whether potential benefits result from the intraoperative anesthetic technique, from the postoperative pain regimen, or from a combination of the two. Also, there is little evidence from well-designed clinical studies to demonstrate improved pulmonary outcome with regional anesthetic techniques. However, a recent review of the role of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in surgical practice, by Moraca and associates (166), indicates that epidural anesthesia/analgesia may improve postoperative outcome. Specifically, in four large studies they assessed involving high-risk (aortic reconstruction) surgery patients, significant reductions in cardiac morbidity were associated with use of intraoperative and postoperative epidural anesthesia/analgesia using local anesthetics plus opioids (166). In addition, they concluded that intraoperative epidural administration of local anesthetics may blunt the physiologic hypercoagulable surgical stress response and thus modify the perioperative hypercoagulable state, stating "reductions in morbidity due to thrombotic complications in complex vascular operations make epidural anesthesia and analgesia the standard of care in these settings" (166). Perhaps the only substantial clinical benefit of regional anesthetic techniques in patients undergoing vascular surgery is enhanced postoperative graft patency. Christopherson and co-workers (174) and Tuman and co-workers (7) report an approximately five-fold greater incidence of graft occlusion following general anesthesia alone. The proposed mechanism that perhaps explains this observation is that general anesthesia alone is associated with a hypercoagulable state in the immediate postoperative period, whereas regional anesthetic techniques may attenuate this effect (176). It appears from several studies that fibrinolysis is decreased after general anesthesia yet is normal following regional anesthesia. These findings may be linked to stress response attenuation with regional anesthesia, thus profoundly affecting postoperative catecholamines, acute phase reactants, and platelets. Another important potential mechanism for increased lower extremity graft patency with regional anesthetic techniques may be increased lower extremity blood flow associated with sympathectomy (177). Thus, as with cardiac surgery, clear deficiencies in the literature prohibit definitive analysis of the risk-benefit ratio of intrathecal and epidural anesthesia and analgesia techniques as applied to patients undergoing vascular surgery. Although some evidence from meta-analyses suggest that there may be benefits from regional anesthetic techniques on postoperative pulmonary complications, postoperative myocardial infarction, and even mortality, these have mostly not been confirmed by recent randomized controlled clinical trials. In summary, although regional anesthetic techniques certainly provide excellent pain relief following vascular surgery, the supposition that the techniques decrease morbidity and mortality remains unproven. Spinal anesthesia to upper thoracic dermatomes produces a decrease in mean arterial blood pressure that is accompanied by a parallel decrease in coronary blood flow (178,179). Exactly what percentage of blood pressure decrease is acceptable remains speculative, especially in patients with coronary artery disease. Disturbances in myocardial oxygenation appear to occur in patients with coronary artery disease if coronary perfusion pressure is allowed to decrease by more than 50% during induction of thoracic epidural anesthesia with local anesthetics (180). Furthermore, if -adrenergic agonists are used to increase blood pressure during this time, detrimental effects (vasoconstriction) may occur on the native coronary arteries and bypass grafts (181,182). Hypotension also appears to be relatively common when thoracic epidural local anesthetics are used in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Volume replacement, -adrenergic agonists, and/or -adrenergic agonists are required in a fair proportion of patients, and coronary perfusion pressure may decrease in susceptible patients. In fact, myocardial depression has been detected in patients receiving thoracic epidural anesthesia with bupivacaine, a clinical effect at least partially caused by increased blood concentrations of the drug (184). Concomitant use of -adrenergic blockers may further decrease myocardial contractility in this setting (185,186). Patients undergoing cardiac surgery who were randomized to receive intermittent boluses of thoracic epidural bupivacaine intraoperatively followed by continuous infusion postoperatively exhibited significantly increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressures following cardiopulmonary bypass when compared with patients managed similarly without epidural catheters (10. Two case reports also indicate that the use of epidural anesthesia and analgesia may either mask myocardial ischemia or initiate myocardial ischemia (187,188). Oden and Karagianes describe the perioperative course of an elderly patient who had a history of exertional angina and underwent uneventful cholecystectomy (188). Easley and associates describe the perioperative course of a middle-aged patient without cardiovascular symptoms ("borderline" hypertension) who was scheduled for exploratory laparotomy (187). Prior to surgery, a low thoracic epidural catheter was inserted and local anesthetic was administered (sensory level peaked by pin-prick at T2). The patient at this time began complaining of left-sided jaw pain, and substantial (2. Surgery was cancelled, and the patient was treated with aspirin and nitroglycerin. Coronary angiography on the following day was unremarkable, and a presumptive diagnosis of coronary artery spasm was made. It was believed by these authors that low thoracic epidural-induced sympathectomy led to alterations in the sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. Following administration of intrathecal or epidural opioids, the most common side effect is pruritus. The incidence varies widely (from 0% to 100%) and is often identified only after direct questioning of patients. The incidence of urinary retention varies widely (from 0% to 80%), and occurs most frequently in young male patients. When intrathecal or epidural opioids are used in patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery, the incidence of pruritus, nausea and vomiting, and urinary retention is similar to that just described.

Buy genuine ritonavir on line

Similar ganglia are present around the origin of the superior mesenteric artery coming from a lower origin in the spine medications you can take while nursing discount 250 mg ritonavir amex. These ganglia contain the soma of the postganglionic sympathetic neurons providing vascular tone to the abdominal vascular structures, as well as regulation of hormonal and metabolic functions of the viscera. Through these ganglia pass the preganglionic parasympathetic neurons that connect with their terminal synapses in the viscera that they are traveling to . The ganglia also include sensory afferent fibers that carry pain signals from the abdominal viscera and peritoneum. Another important visceral sensory structure is the superior hypogastric plexus located in front of the sacral promontorium. However, it has been recognized that the phrenic nerves also provide sensory visceral innervation to the diaphragm from both the thoracic as well as the abdominal directions. In fact, because the phrenic nerves share dermatomes with the somatic innervation of the shoulder, patients who have had intrathoracic procedures frequently complaint about ipsilateral shoulder pain in spite of excellent incisional and chest tube area analgesia. However, this pain can also result from other sources including myocardial ischemia, a chest drain impinging on the apex of the pleura and the brachial plexus, and malposition or compression of the shoulder during the surgery (see also Chapter 45). Consideration should be given to this innervation when 520 Chapter 23: Neural Blockade for Abdominal and Thoracic (Non-vascular) Surgery 521 esophageal surgery is planned with a neck (as well as thoracic) incision (1). Physiologic Considerations of Thoracic Epidural Blockade Cardiovascular Effects Cardiovascular changes occur when local anesthetics are injected into the thoracic epidural space. The extension and intensity of the changes depend upon the volume/mass of local anesthetic injected, the age of the patient, and the spinal level at which the anesthetic agents are deposited. These factors affect the impact on the sympathetic nervous system produced by the local anesthetics. The nerve roots in the intervertebral foramina contain afferent sympathetic fibers, as well as efferent fibers regulating the "tone" of the vascular structures they innervate. These are small neurons that are easily blocked by small concentrations of local anesthetics, leaving the arteries and veins to regulate their caliber in a "low-resistance state. Pooling of venous blood decreases central venous pressure, cardiac output, and subsequently, blood pressure (2). A compensatory vasoconstriction in the vasculature of the unblocked regions may attenuate to certain extent the drop in blood pressure and increase cardiac output in healthy individuals. Thoracic epidural anesthesia leads to compensatory reduction of myocardial work and oxygen demand. As shown by echocardiographic testing, a reduction in mean arterial pressure leads to myocardial wall motion dysfunction only during lumbar epidural anesthesia, not during thoracic epidural anesthesia (4) (see Chapter 11). The visceral sympathetic innervation reaching the suprarenal gland will also be blocked. As a consequence, the systemic circulation of catecholamines released by the adrenal gland will decrease, thus compounding the drop in peripheral resistance, venous return, cardiac output, and blood pressure. Hypotension can be profound in patients with poor cardiovascular reserve and requires prompt action to correct. On the other hand, hypotension and hypoperfusion of the respiratory centers in the brainstem from thoracic blockade can produce severe changes in the respiratory physiology (see Chapter 11). Mankikian also demonstrated that postoperative thoracic epidural block corrects postoperative diaphragmatic dysfunction. The unopposed bronchial reactivity due to the sympathetic blockade might be attenuated by the systemic effect of the local anesthetics (see Chapter 11). General anesthesia, postoperative immobilization, and systemic administration of opioids and sedative drugs adversely affect ventilation and gas exchange and cause respiratory complications. An ideal anesthesia and analgesia technique for thoracotomy should be rapid in onset, facilitate recovery, and should provide optimum analgesia for a minimum of 3 postoperative days (as long as chest drains are in situ). Patients should be able to move, take deep breaths, produce effective coughs, and cooperate with physiotherapy. The most common regional anesthesia techniques for thoracic surgical procedures involving the opening of the chest include thoracic epidural, paravertebral, intercostal, and interpleural blockade. Thoracic Epidural Blockade Thoracic epidural anesthesia is achieved by approaching the epidural space with a paramedian or mid-line technique. Thoracic epidural anesthesia has been used for lung, chest wall, esophageal, and plastic/reconstructive surgeries (see Chapter 11). Epidural local anesthetics increase Pao2 and decrease the incidence of pulmonary infections and pulmonary complications overall. Effectiveness of the sensory block should be established before induction of general anesthesia with either cold or pin-prick testing and by autonomic response such as a decrease in blood pressure or pupillary reflex dilation in response to noxious stimulation (13). Intraoperative thoracic epidural blockade has been shown to decrease chronic pain after thoracotomy (14,15). One-lung ventilation causes significant increases in shunt fraction associated with a decrease in Pao2. Shunt fraction and alveolar-arterial differences in Pao2 do not change with thoracic epidural anesthesia. To affect the mechanical function of the intercostal muscles, a thoracic epidural blockade would require a highly concentrated local anesthetic covering segments from T2 to T8. It is suggested that patients with cardiopulmonary disease and impaired oxygenation before one-lung ventilation might benefit from thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with general anesthesia. In a meta-analysis of 65 studies, Ballantyne and associates concluded that postoperative epidural pain control may significantly decrease pulmonary morbidity (17). The Direct Search Procedure technique has been utilized to find proper doses, infusion rates, and combinations of drugs to achieve optimal analgesia with thoracic epidural anesthesia (19,20). A sophisticated mathematical model tested multiple solutions and infusion rates based on bupivacaine, fentanyl, and clonidine. The three best combinations of bupivacaine dose (mg/h), fentanyl dose (g/h), clonidine dose (g/h), and infusion rate (mL/h) were: 9-21-5-7, 8-30-0-9, and 13-250-9. Adding epinephrine to mixtures of opioids with low-concentration solutions of local anesthetics has proven beneficial for thoracic epidural analgesia (20), but the role of clonidine remains undetermined. Epidural catheters placed in the lumbar area for thoracic/upper abdominal surgery require hydrophilic opioids to produce analgesic effects in the thoracic region. To achieve maximal analgesia, the epidural catheter should be placed in the dermatome corresponding to the mid-point of the surgical incision. Increasing the infusion rate to improve analgesia produces unwanted motor blockade in the lower extremities and impairs mobilization. Likewise, catheters inserted above T4 tend not to cover the insertion site of the chest drains, producing only partial analgesia. Blocking the upper thoracic dermatomes is usually accompanied by hypotension secondary to cardiac sympathetic blockade, decrease in cardiac output, and blockade of the sympathetic innervation of the suprarenal glands. Compensatory sympathetic activity and vasoconstriction occur in the nonblocked distal territories (25,26). Moderate intravascular volume load and cardiostimulant drugs are recommended to reestablish cardiac output and blood pressure in this scenario. Up to 50% of the patients faint when placed in the sitting position for epidural catheterization (27). Sedation and glycopyrrolate or atropine before the procedure may decrease this side effect. Postoperative analgesia may be associated with primary failure (inadequate analgesia immediately postoperatively) or secondary failure (initial ad- equate analgesia followed by an increase in pain/inadequate analgesia).

Discount ritonavir 250mg mastercard

No single algorithm or guideline can address the management challenges for a heterogenous patient population symptoms zenkers diverticulum buy discount ritonavir 250 mg on-line. A patient-centered approach, with individualized regimes, including procedures and drugs, will ensure a high standard of patient comfort without compromising safety. Patient comfort during regional anesthesia is also an important teaching point for trainees (9). In ensuring patient comfort during regional anesthesia, several steps are involved. Both cart-based and portable, compact ultrasound machines are now available and suited for nerve imaging. In theory, visual guidance can impart confidence to anesthesiologists, improve safety of patients, and enhance efficient time utilization in the operating room. Outcomes data to demonstrate convincingly that the clinical benefits of ultrasound are pending. There is no doubt that this imaging technology will be a valuable and enduring part of practice in regional anesthesia. In this article, where relevant, ultrasound-guided block techniques and available literature will be discussed. Preoperative Preparation, Psychology and Communication Psychology and communication play an important part in the success of any anesthetic technique (10). Premedication Pharmacologic premedication facilitates patient comfort during regional anesthesia performance (11). Advantages of premedication include improved patient satisfaction, acceptance, and cooperation. Disadvantages include unpredictable response, side effects, and interference with cooperation (12). In some cases, particularly with elderly patients and in ambulatory surgery, premedication is omitted. General Principles of Ultrasound-guided Nerve Block Techniques Certain general principles apply to the successful use of ultrasound to guide nerve block techniques: the quality of ultrasonographic nerve images is dependent on the quality of the ultrasound machine and transducers, proper transducer selection. Sterile conducting gel and a sterile plastic sheath to fully cover the entire transducer should be used especially for catheter techniques. Ultrasonography provides anatomic information, while a motor response to nerve stimulation provides functional information about the nerve in question. Observing local anesthetic spread is a valuable feature of ultrasound in addition to real-time visual guidance to navigate the needle toward the target nerve. This approach is preferred when it is important to track the needle tip at all times. In this case, the ultrasound image captures a transverse view of the needle, which is shown as a hyperechoic "dot" on the screen. Accurate moment-to-moment tracking of the needle tip location can be difficult, and needle tip position is often inferred indirectly by tissue movement and local anesthetic spread. This approach, however, is particularly useful for continuous catheter placement along the long axis of the nerve. A: Short-axis needle approach with block needle perpendicular to the ultrasound beam. T12 is not an intercostal nerve because it does not run a course between two ribs; it is more appropriately termed a subcostal nerve. Some of its fibers unite with fibers from the first lumbar nerve and are terminally represented as the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. The first are the paired gray and white rami communicantes, which pass anteriorly to and from the sympathetic ganglion and chain. The second branch arises as the posterior cutaneous branch and supplies the skin and muscles in the paravertebral region. The third branch is the lateral cutaneous division, which arises just anterior to the midaxillary line. This branch is of most concern to the anesthesiologist because it immediately sends subcutaneous fibers coursing both posteriorly and anteriorly to supply skin of much of the chest and abdominal wall. In the upper five nerves, this branch terminates after penetrating the external intercostal and pectoralis major muscles to innervate the breast and front of the thorax. The lower six anterior cutaneous nerves terminate after piercing the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle, to which they supply motor branches. Some final branches continue an- teriorly and become superficial near the linea alba, to provide cutaneous innervation to the midline of the abdomen. Medial to the posterior angles of the ribs, the intercostal nerves lie between the pleura and the fascia of the internal intercostal muscle. In the paravertebral region, there is only fatty connective tissue between nerve and pleura. At the angle of the rib (6 to 8 cm from the spinous processes), the nerve comes to lie between the internal intercostal muscle and the intercostalis intimus muscle. Cadaver studies have shown that the nerve itself remains subcostal only 17% of the time, has most frequently (73%) moved inferiorly into the midzone between ribs, and is often branching at this point (16). The costal groove becomes a sharp inferior edge of the rib, about 5 to 8 cm anterolateral to the angle of the rib. Note also (a) the spinal nerves and dorsal root ganglia in the region of intervertebral foramen, with risk of perineurial spread into spinal fluid after intraneural injection in this region; (b) direct injection into an intervertebral foramen may reach spinal fluid by means of a dural cuff; (c) local anesthetic may gain access to epidural space by diffusing into an intervertebral foramen; (d) close to the midline, the intercostal nerve lies directly on the posterior intercostal membrane and pleura; and (e) paravertebrally, solution may diffuse to rami communicantes and sympathetic chain. Section is shown in region of costal groove, which extends from near the head of the rib to 5 to 8 cm anterior to the angle of the rib. At the level of the angle of the rib, the intercostal nerve (one or more) lies inferior to vein and artery in the intercostal groove. The prone position is particularly favored if bilateral blocks are to be performed. A pillow is placed under the abdomen to decrease the lumbar lordosis and to accentuate the intercostal spaces posteriorly. The arms should be allowed to hang down from the edge of the block table to permit the scapula to rotate as far laterally as possible. The next step is to palpate laterally to the edge of the sacrospinalis group of muscles, where the ribs are most superficial. This distance is somewhat variable, depending on body size, muscle mass, and physique, but is usually 6 to 8 cm from the midline. Subsequent lines are drawn somewhat parallel to the first one, but with a trend to angle medially at the upper levels as the sacrospinalis muscles taper, so as to avoid the scapulae. The caudal end of the line should cross near the end of the shortened twelfth rib, which is generally easy to palpate. For thoracic or other unilateral chest wall surgery, only the appropriate side and ribs are marked. The needle insertion point is infiltrated with local anesthetic using a 25-gauge needle. The ribs and intercostal spaces are thicker at the angle of the rib, allowing a larger margin of safety before pleura is contacted. Note finger palpating rib still in place and hand holding syringe firmly braced against back. The lowest (most inferior) intercostal nerve is blocked first because the lower ribs are easy to palpate. Note left hand now rests against the back and holds the needle as it is walked off the inferior edge of the rib and advanced 3 mm. A 25-gauge 15-mm or a 23-gauge 25-mm needle is introduced in 20-degree cephalad orientation through the skin between the tip of the retracting fingers and advanced until it contacts rib. Intercostal nerve blocks can also be placed at the midaxillary line while the patient is lying supine. A systematic review of randomized trials indicates that intercostal infusion provides analgesia that is at least as effective as an epidural and significantly better than systemic opioids alone (21). The ribs appear as dense, dark oval structures with a bright surface (periosteum). A dark shadow is cast deep to the rib on ultrasound, illustrating the phenomenon of echo shadowing.