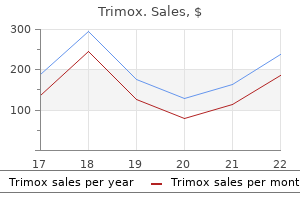

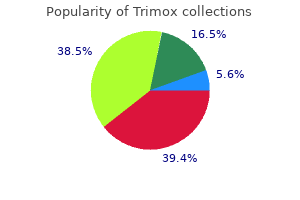

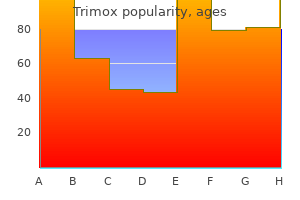

Trimox 500mg lowest price

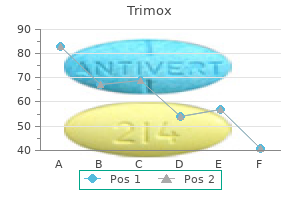

Pulmonary Venules and Veins Pulmonary capillary blood is collected into venules that are structurally almost identical to the arterioles virus facts buy trimox 250mg low cost. In fact, Duke34 obtained satisfactory gas exchange when an isolated cat lung was perfused in reverse. The pulmonary veins do not run alongside the pulmonary arteries but lie some distance away, close to the septa which separate the segments of the lung. Most of the lymph from the left lung usually enters the thoracic duct whilst the right side drains into the right lymphatic duct. However, the pulmonary lymphatics often cross the midline and pass independently into the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian veins on the corresponding sides of the body. The acoustic reflection technique for non-invasive assessment of upper airway area. Acoustic reflectometry for airway measurements in man: implementation and validation. Smaller is better- but not too small: a physical scale for the design of the mammalian pulmonary acinus. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Alveolar volumesurface area relation in air and saline filled lungs fixed by vascular perfusion. Three-dimensional architecture of elastin and collagen fiber networks in the human and rat lung. Bronchial Circulation35 the conducting airways (from trachea to the terminal bronchioles) and the accompanying blood vessels receive their nutrition from the bronchial circulation which arises from the systemic circulation. The bronchial circulation therefore provides the heat required for warming and humidification of inspired air, and cooling of the respiratory epithelium causes vasodilation and an increase in the bronchial artery blood flow. About one third of the bronchial circulation returns to the systemic venous system, the remainder draining into the pulmonary veins, constituting a form of venous admixture (page 125). The bronchial circulation also differs from the pulmonary circulation in its capacity for angiogenesis. As a result, the blood supply to most lung cancers (Chapter 29) is derived from the bronchial circulation. Pulmonary Lymphatics There are no lymphatics visible in the interalveolar septa, but small lymph vessels commence at the junction between alveolar and extraalveolar spaces. There is a well-developed lymphatic system around the bronchi and pulmonary vessels, capable of containing up to 500 ml of lymph, and draining towards the hilum. Down to airway generation 11 the lymphatics lay in a potential space around the air passages and vessels, separating them from the lung parenchyma. This space becomes distended with lymph in pulmonary oedema and accounts for the characteristic butterfly shadow of the chest radiograph. The effects of dobutamine and dopamine on intrapulmonary shunt and gas exchange in healthy humans. Biomechanics of the lung parenchyma: critical roles of collagen and mechanical forces. The bioengineering dilemma in the structural and functional design of the blood-gas barrier. Ultrastructural appearances of pulmonary capillaries at high transmural pressures. Mouth breathing and nasal breathing are controlled by pharyngeal muscles, particularly those of the tongue and soft palate. Mouth breathing becomes obligatory with nasal obstruction from common diseases and is required when hyperventilating for example, during exercise, to reduce respiratory resistance to high gas flows. Fine control of vocal fold position and tension is also achieved by the larynx to facilitate phonation, the laryngeal component of speech. This requires excellent coordination between the respiratory and laryngeal muscles to achieve the correct, and highly variable, airflows through the vocal folds. Airway integrity is maintained by the presence of cartilage in the airway walls down to about the eleventh generation (small airways with diameter 1 mm) but beyond this airway patency is dependent on the elasticity of the surrounding lung tissue in which the airway is embedded. The epithelium is mostly made up of ciliated cells: pseudostratified in the upper airway, columnar in large airways and cuboidal in bronchioles. Other cells in the epithelium are basal cells (the stem cells for other cell types), mast cells and nonciliated epithelial cells (Clara cells) of uncertain function. The epithelial cells lining acinar airways gradually thin from cuboidal in the terminal bronchioles to become continuous with the alveolar epithelial cells. A fibre scaffold of collagen and elastin maintains the structure of the acinus, with interconnected axial fibres running along the airways, peripheral fibres extending from the visceral pleura into the lung tissue and septal fibres forming the alveolar structure itself. This basketlike structure of fibres includes many components under tension, such that when a small area is damaged large holes can occur as seen, for example, in emphysema. Alveoli contain type 1 epithelial cells over the gas exchange area, type 2 epithelial cells in the corners of the alveoli which produce surfactant and are the stem cells for type 1 cells, and alveolar macrophages responsible for removal of inhaled particles in the alveolus. Pulmonary blood vessels branch in a similar pattern to their corresponding airways, and, unlike their systemic counterparts, are virtually devoid of muscular tissue. Pulmonary capillaries form a dense network around the walls of alveoli, weaving across the septa and bulging into the alveoli with their active sides exposed to the alveolar gas. The bronchial circulation is separate from the pulmonary circulation, arising from the systemic circulation and supplying the conducting airways, with some of its venous drainage returning to the right side of the systemic circulation and some draining directly into the pulmonary veins. An isolated lung will tend to contract until eventually all the contained air is expelled. Thus in a relaxed subject with an open airway and no air flowing, for example, at the end of expiration or inspiration, the inward elastic recoil of the lungs is exactly balanced by the outward recoil of the thoracic cage. The movements of the lungs are entirely passive and result from forces external to the lungs. With spontaneous breathing the external forces are the respiratory muscles, whereas artificial ventilation is usually in response to a pressure gradient developed between the airway and the environment. In each case, the pattern of response by the lung is governed by the physical impedance of the respiratory system. Work performed in overcoming elastic resistance is stored as potential energy, and elastic deformation during inspiration is the usual source of energy for expiration during both spontaneous and artificial breathing. This chapter is concerned with the elastic resistance afforded by lungs (including the alveoli) and chest wall, which will be considered separately and then together. Compliance is usually expressed in litres (or millilitres) per kilopascal (or centimetres of water) with a normal value of 1. Compliance may be described as static or dynamic depending on the method of measurement (page 29). Elastance is the reciprocal of compliance and is expressed in kilopascals per litre. The Nature of the Forces Causing Recoil of the Lung For many years it was thought that the recoil of the lung was due entirely to stretching of the yellow elastin fibres present in the lung parenchyma. In 1929 von Neergaard (see section on Lung Mechanics in online Chapter 2: the History of Respiratory Physiology) showed that a lung completely filled with and immersed in water had an elastance that was much less than the normal value obtained when the lung was filled with air. Thus the gas pressure within a bubble is always higher than the surrounding gas pressure because the surface of the bubble is in a state of tension. Alveoli resemble bubbles in this respect, although the alveolar gas is connected to the exterior by the air passages. Thus gas would tend to flow from smaller alveoli into larger alveoli and the lung would be unstable which, of course, is not true. Similarly, the retractive forces of the alveolar lining fluid would increase at low lung volumes and decrease at high lung volumes, which is exactly the reverse of what is observed. These paradoxes were clear to von Neergaard and he concluded that the surface tension of the alveolar lining fluid must be considerably less than would be expected from the properties of simple liquids and, furthermore, that its value must be variable. Observations 30 years later confirmed this when alveolar extracts were shown to have a surface tension much lower than water and which varied in proportion to the area of the interface. As the bar is moved to the right, the surface film is concentrated and the surface tension changes as shown in the graph on the right of the figure. The course of the relationship between pressure and area is different during expansion and contraction, and a loop is described. In contrast to a bubble of soap solution, the pressure within an alveolus tends to decrease as the radius of curvature is decreased. Gas tends to flow from the larger to the smaller alveolus and stability is maintained.

Purchase trimox master card

Progressive loss of intracortical inhibition following traumatic brain injury detected by transcranial magnetic stimulation and mechanomyogram in rats 700 bacteria in breast milk discount trimox 500 mg without a prescription. Neuroprotective effect of ceftriaxone on the penumbra in a rat venous ischemia model. Ceftriaxone preserves glutamate transporters and prevents intermittent hypoxia-induced vulnerability to brain excitotoxic injury. The glutamate and neutral amino acid transporter family: physiological and pharmacological implications. Early expression of glutamate transporter proteins in ramified microglia after controlled cortical impact injury in the rat. Loss of parvalbumin interneurons underlies impaired cortical inhibition in post-traumatic epileptogenesis. Mechanism of ceftriaxone induction of excitatory amino acid transporter-2 expression and glutamate uptake in primary human astrocytes. The number of glutamate transporter subtype molecules at glutamatergic synapses: chemical and stereological quantification in young adult rat brain. Selective vulnerability of dentate hilar neurons following traumatic brain injury: a potential mechanistic link between head trauma and disorders of the hippocampus. The role of glutamate receptors in traumatic brain injury: implications for postsynaptic density in pathophysiology. Prolonged memory impairment in the absence of hippocampal cell death following traumatic brain injury in the rat. High-density microarray analysis of hippocampal gene expression following experimental brain injury. Immature cortical neurons are uniquely sensitive to glutamate toxicity by inhibition of cystine uptake. Astrocytic glutamate transporter-dependent neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity: an in vitro study of maslinic acid. Glutamate uptake disguises neurotoxic potency of glutamate agonists in cerebral cortex in dissociated cell culture. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Noninvasive brain stimulation to modulate neuroplasticity in traumatic brain injury. Hippocampal immediate early gene transcription in the rat fluid percussion traumatic brain injury model. The beta-lactam antibiotic, ceftriaxone, provides neuroprotective potential via anti-excitotoxicity and anti-inflammation response in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Once the conceptual context has been established, pharmacological properties, proposed mechanisms of action, and empirical studies relating to memantine in particular will then be summarized. In contrast, memantine is an open-channel blocker, which yields qualitatively distinct pharmacological properties and a more benign side effect profile. Intracellular targets include signaling molecules such as kinases, phosphatases, other enzymes, and scaffold proteins. Unacceptable psychotomimetic side effects for these drugs, such as hallucinations and coma, were identified during clinical trials for stroke. Furthermore, the uncompetitive nature of memantine suggests that the proportion of the current blocked by the drug should increase in response to higher levels of glutamate, such as those seen in acute ischemia, while the block should be minimal when agonist levels are low (Chen et al. Additionally, memantine demonstrates rapid blocking and unblocking kinetics at low concentrations. One early hypothesis was formulated to account for the symptomatic improvement observed with memantine (eg, improved memory), rather than prevention of ongoing chronic neurodegeneration or neuroprotection from an acute insult. This hypothesis posited that hyperglutamatergic states increased synaptic "noise," thereby limiting the capacity to detect true physiological signal, effectively decreasing the signal-to-noise ratio. It is possible that synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors are linked to different signaling complexes or that different subunit compositions (eg, GluN2A vs GluN2B) are associated with different molecular cascades. Memantine is currently available in three formulations: oral solution, tablet, and extended-release capsule. The manufacturer recommends gradual titration, beginning at one-quarter of the full dose, with incremental increases of the same dose at weekly intervals, until the target dose is reached. At these doses, the most common side effects include dizziness, headache, confusion, and constipation. Renal clearance involves active tubular secretion moderated by pH-dependent tubular reabsorption. As such, dosage reduction should be considered in conditions that alkalinize the urine (eg, urinary tract infections, use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, or administration of sodium bicarbonate) since these could lead to increased drug accumulation in the plasma. A dosage adjustment is not recommended for patients with mild to moderate hepatic failure, but the drug should be used with caution in patients with severe renal failure. Caution would also be indicated in treating pregnant patients, nursing mothers, children, and patients with concurrent seizure disorder since safety and efficacy have not been established in well-validated studies involving these populations. Co-administration of drugs that rely on the same renal cationic system for elimination of memantine could affect plasma levels of both drugs. The authors then explored the impact of memantine on indirect excitotoxicity, namely stress models that rely upon energy depletion and endogenous glutamate release. Promising results with memantine have also been reported in rodent models of ischemic stroke. In summary, memantine appears to provide some degree of neuroprotection to hippocampal, cerebellar, and cortical cells in various models of direct and indirect excitotoxicity. It also reduces neuronal damage secondary to hypoxicischemic events and, therefore, improves neurological outcomes. Memantine appears to provide neuroprotection from excitotoxic insults in a dose-dependent fashion. A small number of preclinical studies have studied combination therapies, in which memantine is one component. Combination therapy (100 pM 17-estradiol and 10 M memantine) was more effective than either monotherapy alone and remained neuroprotective when administered at 1 h postinjury (but not 2 h postinjury). Prior research from this group had shown that memantine reduced hematoma volume but not brain edema, while the converse pattern was true for celecoxib (ie, celecoxib reduced edema but not hematoma volume). Similarly, memantine monotherapy was effective in attenuating apoptotic caspase-3 activity, yielding no significant difference between memantine monotherapy and combination therapy. Overall, the findings of this study suggest that memantine was relatively effective in targeting hemorrhage volume and apoptosis, while celecoxib was fairly effective in targeting cerebral edema and inflammation. The combination treatment was effective in targeting multiple facets of neuropathology in a way that was not achieved by either monotherapy, presumably secondary to pharmacologic effects upon several pathophysiological pathways (Sinn et al. Although behavioral performance was similarly improved by the combination therapy and monotherapies, it is possible that behavioral distinctions could be identified on more sensitive or complex tasks were they to be administered to humans in a clinical trial. Unfortunately, this study did not include an appropriate comparison group, such as a placebo group. It included a heterogeneous group of patients, most of whom had been injured less than 6 months before treatment initiation. In the context of human injuries, patients sometimes have not been transported to specialized trauma centers and diagnosed with brain injury within the initial golden hour. It is possible that pretreatment or concurrent treatment with memantine could confer some neuroprotection from these secondary insults. Several studies have used accelerated titration schedules and higher maximal doses in various disorders. Undesirable side effects, such as dizziness and fatigue, are more likely to be observed with high doses or accelerated titration schedules (Thurtell et al. This could potentially be most directly evaluated by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Alternatively, it could be attempted empirically in patients who exhibit chronic memory problems at the time of treatment initiation. The ideal dose, titration schedule, and treatment duration for any given patient subpopulation or indication remain to be determined. Furthermore, preclinical studies have shown that memantine also confers neuroprotection to cerebellar and cortical cells. However, even with delayed treatment initiation, memantine may confer some neuroprotection from secondary ischemic injuries and Wallerian degeneration. Rather, the rationale for this indication relies almost entirely on symptomatic improvement observed in other disorders.

Cheap 500 mg trimox fast delivery

Four pathways are involved in controlling muscle tone in small bronchi and bronchioles: 1 virus 68 affecting children discount 250mg trimox overnight delivery. Local cellular mechanisms these may conveniently be considered as discrete mechanisms, but in practice there is considerable interaction between them, particularly in disease. Neural control is the most important in normal lung, with direct stimulation and humoral control contributing under some circumstances. Cellular mechanisms, particularly mast cells, have little influence under normal conditions but are important in airway disease (Chapter 27). Neural Pathways14,15 Parasympathetic System this system is of major importance in the control of bronchomotor tone and when activated can completely obliterate the lumen of small airways. Afferents arise from receptors under the tight junctions of the bronchial epithelium and respond either to noxious stimuli acting directly on the receptors (see later) or from cytokines released by cellular mechanisms such as mast cell degranulation. In addition, expiration from total lung capacity at four levels of expiratory effort are shown. Within limits, peak expiratory flow rate is dependent on effort but, during the latter part of expiration, all curves converge on an effort-independent section where flow rate is limited by airway collapse. The pips above the effort-independent section probably represent air expelled from collapsed airways. Some degree of resting tone is normally present15 and therefore may permit some degree of bronchodilation when vagal tone is reduced in a similar fashion to vagal control of heart rate. The reflex is not a simple monosynaptic reflex, because there is considerable central nervous system modulation of the response, which offers a potential role for the brain in controlling the degree of airway hyperresponsiveness in lung disease. Indeed it appears unlikely that there is any direct sympathetic innervation of the airway smooth muscle, although there may be an inhibitory effect on cholinergic neurotransmission in some species. Noncholinergic Parasympathetic Nerves15 the airways are provided with a third autonomic control which is neither adrenergic nor cholinergic. This is the only potential bronchodilator nervous pathway in man, though the exact role of these nerves in humans remains uncertain. Physical and Chemical Effects Direct stimulation of the respiratory epithelium activates the parasympathetic reflex as previously described causing bronchoconstriction. Physical factors known to produce bronchoconstriction include mechanical stimulation of the upper air passages by laryngoscopy and the presence of foreign bodies in the trachea or bronchi. Inhalation of particulate matter, an aerosol of water or just cold air may cause bronchoconstriction, the latter being used as a simple provocation test. Many chemical stimuli result in bronchoconstriction including liquids with low pH such as gastric acid and gases such as sulphur dioxide, ammonia, ozone and nitrogen dioxide. However, cardiac effects from 1-receptor stimulation in the heart were believed to be responsible for an increase in mortality during acute asthma, and the development of 2-specific drugs. The therapeutic effect of 2-agonists is more complex than simple relaxation of airway smooth muscle as they are also known to inhibit the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and most of the bronchoconstrictor mediators shown in Table 3. These inflammatory cells are all stimulated by a variety of pathogens, but some may also be activated by the direct physical factors described in the previous paragraph. Once activated, cytokine production causes amplification of the response, and a variety of mediators are released that can cause bronchoconstriction (Table 3. The agonist binds to three amino acid residues on the third and fifth transmembrane domains, and by doing so stabilizes the receptor G-protein complex in the activated state. The intracellular C-terminal region of the protein (green) is the area susceptible to phosphorylation by intracellular kinases causing inactivation of the receptor and downregulation. The agonist binding site is within this hydrophobic core of the protein, which sits within the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. This affects the interaction of drugs at the binding site in that more lipophilic drugs form a depot in the lipid bilayer from which they can repeatedly interact with the binding site of the receptor, producing a much longer duration of action than hydrophilic drugs. Studies of these phenotypes continue, with some differences observed between individuals in terms of clinical picture or response to therapy,24,25 but the contribution that different 2-receptor phenotypes make to the overall prevalence of asthma appears to be minimal. Tachykinin, histamine and leukotriene receptors responsible for bronchoconstriction from other mediators (Table 3. Activation of phospholipase C by protein Gq also liberates intracellular diacylglycerol that activates another membrane-bound enzyme protein kinase C. They are more useful in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than asthma (Chapter 27), because only in the former disease is increased parasympathetic activity thought to contribute to symptoms. These drugs have similar binding affinities for both M2 and M3 receptors, giving rise to opposing effects on the degree of stimulation of airway smooth muscle. Differences in relative numbers of M2 and M3 receptors between individuals and in different disease states14 will therefore explain the variability in response seen with inhaled anticholinergic drugs. Inflammatory mediators stimulate phospholipase A2 to produce arachidonic acid from the phospholipid of the nuclear membrane. Leukotriene Antagonists30 Even in nonasthmatic individuals, leukotrienes are potent bronchoconstrictors, so the therapeutic potential of leukotriene antagonists has been extensively investigated. Activation of phospholipase A2 by inflammatory cells initiates the pathway, which ultimately produces three leukotrienes (Table 3. Leukotrienes have a wide range of activities apart from bronchoconstriction, in particular amplification of the inflammatory response by chemotaxis of eosinophils. They are therefore most likely to be of benefit in prevention of bronchospasm in chronic asthma, but their place in asthma therapy remains uncertain. There are two principal mechanisms of compensation for increased inspiratory resistance. The first operates immediately and even during the first breath in which resistance is applied. It seems probable that the muscle spindles indicate that the inspiratory muscles have failed to shorten by the intended amount, and their afferent discharge then augments the activity in the motoneurone pool of the anterior horn. This is the typical servo operation of the spindle system with which the intercostal muscles are richly endowed (page 79). This reflex, mediated at the spinal level, is preserved during general anaesthesia (page 310). In awake humans, the spinal response is accompanied by a further stimulus to ventilation mediated in suprapontine areas of the brain, possibly in the cerebral cortex. If the response does indeed depend on cortical activity, this would explain why resistive loading during physiological sleep can be problematic (Chapter 14). Note that there is an immediate augmentation of the force of contraction of the inspiratory muscles. This continues with successive breaths until the elastic recoil is sufficient to overcome the expiratory resistance. Patients show a remarkable capacity to compensate for acutely increased resistance such that arterial Pco2 is usually normal. However, the efficiency of these mechanisms in maintaining alveolar ventilation carries severe physiological consequences. In common with other muscles, the respiratory muscles can become fatigued, which is a major factor in the onset of respiratory failure. A raised Pco2 in a patient with increased respiratory resistance is therefore always serious. Also, intrathoracic pressure will rise during acutely increased expiratory resistance and so impede venous return and reduce cardiac output (page 468) to the point that syncope may occur. Expiratory Resistance Expiration against a pressure of up to 1 kPa (10 cmH2O) does not usually result in activation of the expiratory muscles in conscious or anaesthetised subjects. The additional work to overcome this resistance is, in fact, performed by the inspiratory muscles. In the case of the respiratory tract, the difficulty centres around the measurement of the pressure gradient between mouth and alveolus. Problems also arise because of varying nomenclature and different methods for measuring different components of respiratory system resistance (Table 3. Normal values for total respiratory system resistance are variable because of the large changes with lung volume and methodological differences, but typical values for a healthy male subject are shown in Table 3. For this purpose, pressures were selected at the times of zero air flow when pressures were uninfluenced by air flow resistance. The shaded areas in the pressure trace indicate the components of the pressure required to overcome flow resistance and these may be related to the concurrent gas flow rates. Alternatively, the intrathoracic to mouth pressure gradient and respired volume may be displayed as x- and y-coordinates of a loop. The use of an oesophageal balloon makes the method a little invasive, but it does allow continuous measurement of resistance.

Order trimox 250 mg with visa

In this approach nosocomial infection buy generic trimox on-line, the group facilitator is the process expert, and the group members are the content experts. Yalom and Leszcz suggested that the role of the group leader should be to activate the group and illuminate the here-and-now process of what is occurring between group members. Kottler (2000) and Kottler and Englar-Carlson (2015) reasserted the notion that the person of the group leader is the most useful tool ever present and available to the counselor. Common emotional expressions experienced in counseling include anger outbursts, crying, and laughter. Dopamine is a naturally occurring pleasure hormone released by the brain in anticipation of, or in response to , enjoyable stimuli. Interpersonal Learning Catharsis 190 Neuro-Informed Group Work Reflective Question Group counseling provides an environment for members to wrestle How might you draw on the with the likely sources of dysfuncpower of the group to help tion, such as anxiety regarding the Susan Meaning-making and taking on responsibility are essential to living a life of purpose, not just to managing symptoms. The integration of the brain regions associated with survival (hindbrain), emotions (midbrain), and cognition (forebrain) enables the capacity for higher order thinking, such as the development of insight (Siegel, 2015). Our Brain-Based Approach to Group Counseling Ramachandran (2000) suggested that human brains are best studied in relationship to one another rather than in isolation. However, they do not experience the localized pain (the needle prick) because the brain sends a nullifying message that conflicts with (neutralizes) the mirrored experience. People have the capacity to understand the pain of others as separate from their own, at least under healthy circumstances. This chapter outlined an approach to group work that is experiential and process based, using neuroscientific findings to explain why such an approach can be beneficial. In our brain-based approach to group counseling, we prepared Susan for the group during the planning and prescreening processes. We facilitated positive expectations for the group experience, assisting Susan to tolerate the ambiguity of the group experience. For instance, when Susan experienced the intolerable state of not story-telling, we encouraged her to demonstrate what it felt like to hold back. Through this process, Susan came to develop a new skill set, that of bringing her behavior into harmony-congruence-with her verbalizations. This renewed sense of wholeness played out in her relationships with her group members. Eventually, Susan became more congruent in her relationships outside of group, in her personal life. Conclusion this chapter outlined an approach to group work that is experiential and process based, using neuroscience findings to explain why and how such an approach can be beneficial. Group facilitators do not need extensive neuroscientific knowledge to use the principles of neuro-informed counseling. The numerous points of interactions (dyads and triads) between and among members to which a facilitator must attend. Therapeutic factors that make it difficult for the group to come together to work on their goals. The connections among individuals that produce a network of functioning that is similar to neural networks. The primarily cognitive process in group counseling that requires the use of multiple neural synapses. Nothing is wrong with storytelling because catharsis is one of the therapeutic factors. Group members are often disingenuous and should not be trusted to tell their story. The power of asking: How communication affects selfishness, empathy, and altruism. The neuroscience of human relationships: Attachment and the developing social brain (2nd ed. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Oxytocin conditions intergroup relations through upregulated in-group empathy, cooperation, conformity, and defense. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: A review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Intentional interviewing and counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (8th ed. The human mirror neuron system: A link between action observation and social skills. Mirror neurons and imitation learning as the driving force behind "the great leap forward" in human evolution. The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Brief counseling that works: A solution-focused therapy approach for school counselors and other mental health professionals (3rd ed. Field Neuroscience can inform effective practice in addressing career-related issues. To effectively integrate neuroscience into career counseling, counselors may need to adjust their perspective to see career issues as a clinical mental health counseling presenting problem, like and unlike other presenting problems, rather than as a stand-alone problem. This is an issue of philosophical proportions, so to proceed carefully and as clearly as possible, it is helpful to use translational neuroscience to guide the process. In other words, translational approaches assist with the process of applying basic scientific information to clinical practice (Woolf, 2008). One key approach to using translational neuroscience in career-focused counseling is through metaphors. The purpose of this chapter is to explore how neuroscientific literature and principles offer an innovative, metaphoric perspective on neuro-informed careerfocused counseling. I (Chad Luke) owe a debt of gratitude to Seth Hayden for using this term in a panel presentation at the American Counseling Association Conference and Expo, ushering in new verbiage for describing the work counselors do with career-related issues. Your initial intake paperwork shows that she has been a stay-at-home mom rearing three children for the past 14 years. At this time, her children are in middle and high school and require a different type of active parenting, allowing her time to reflect on her role in the family, community, and world. During the first session, she reports feeling some emptiness as she has entered her 40s and is no longer parenting small children. She thinks she wants to further explore occupational options (simple career advice, right As she has researched job options, she has been experiencing increased anxiety with disrupted sleep, including nightmares about getting fired from jobs. She has a history of generalized anxiety, although it has not been consistently treated or even diagnosed. She states that although her family is stable financially, she wants to make a tangible contribution to the household. Adapted from the work of Savickas (1998), this taxonomy can help counselors and clients make sense of career-focused counseling and neuroscience integration. Zunker (2016) echoed this in describing career-related issues in terms of work environment (inter) and worker traits (intra). This is useful in particular to counselors seeking integration because neuroscientific findings have application to personal (Siegel, 2012) and social (Cozolino, 2010) development. Busacca also identified three areas of career difficulties, broadening the perception of career issues beyond career decision making to career choice, career entry, and career transition. This chapter explores neuroscience applications for both intra- and interpersonal domains, as well as the different levels of career concerns. The relationship between the intrapersonal and interpersonal domains can be understood through the theory of Frank Parsons and Donald Super. Work perforpoint at which she enters mance and satisfaction are optimal counseling The importance of outwardly expressing a self-concept has been emphasized not only by Parsons and Super but also by other important career theorists such as Strong, Holland, and Savickas. Vocational Identity in the Brain So where might one find the self (or, alternatively, the identity) in the brain One proposition is that the self is the totality of experiences and that these experiences are stored as memories-more specifically, as autobiographical memory. Autobiographical memory refers to the memories related to oneself in context: experiences, relationships, and environments.

Cheap trimox 250mg

The laminins are more than simple structural molecules antimicrobial quartz trimox 250 mg generic, having complex interactions with membrane proteins and the intracellular cytoskeleton24 to help regulate cell shape and permeability, etc. The endothelial cells abut against one another at fairly loose junctions of the order of 5 nm wide. Macrophages pass freely through these junctions under normal conditions, and polymorphs can also pass in response to chemotaxis (page 423). Like the endothelium, the flat part of the cytoplasm is devoid of organelles except for small vacuoles. The tightness of these junctions is crucial for prevention of the escape of large molecules, such as albumin, into the alveoli, thus preserving the oncotic pressure gradient essential for the avoidance of pulmonary oedema (see page 408). Nevertheless, these junctions permit the free passage of macrophages, and polymorphs may also pass in response to a chemotactic stimulus. Their position in the lung means alveolar epithelial cells are exposed to the highest concentrations of oxygen of any mammalian cell, and they are sensitive to damage from high concentrations of oxygen (Chapter 24), but recent work suggests they may have active systems for preventing oxidative stress. Note the large nucleus, the microvilli and the osmiophilic lamellar bodies thought to release surfactant. The cytoplasm contains characteristic striated osmiophilic organelles that contain stored surfactant (page 18). They are resistant to oxygen toxicity, tending to replace type I cells after prolonged exposure to high concentrations of oxygen. They can reenter the body but are remarkable for their ability to live and function outside the body. Macrophages form the major component of host defence within the alveoli, being active in combating infection and scavenging foreign bodies such as small dust particles. They contain a variety of destructive enzymes but are also capable of generating reactive oxygen species (Chapter 24). Dead macrophages release the enzyme trypsin, which may cause tissue damage in patients who are deficient in the protein 1-antitrypsin. The media of the pulmonary arteries is about half as thick as in systemic arteries of corresponding size. Pulmonary arteries lie close to the corresponding airways in connective tissue sheaths. Pulmonary Capillaries Pulmonary capillaries tend to arise abruptly from much larger vessels, the pulmonary metarterioles. Inflation of the alveoli reduces the cross-sectional area of the capillary bed and increases resistance to blood flow (Chapter 6). One capillary network is not confined to one alveolus but passes from one alveolus to another, and blood traverses a number of alveolar septa before reaching a venule. From the functional standpoint it is often more convenient to consider the pulmonary microcirculation rather than just the capillaries. These vessels differ radically from their counterparts in the systemic circulation and are virtually devoid of muscular tissue. Structurally there is no real difference between pulmonary arterioles and venules. The Alveolar Surfactant the low surface tension of the alveolar lining fluid and its dependence on alveolar radius are due to the presence of a surface-active material known as surfactant. The fatty acids are hydrophobic and generally straight, lying parallel to each other and projecting into the gas phase. The molecule is thus confined to the surface where, being detergents, they lower surface tension in proportion to the concentration at the interface. After release surfactant initially forms areas of a lattice structure termed tubular myelin, which is then reorganized into monolayered or multilayered surface films. In reality, the situation is considerably more complex, and at present poorly elucidated. Other Effects of Surfactant Pulmonary transudation is also affected by surface forces. Surface tension causes the pressure within the alveolar lining fluid to be less than the alveolar pressure. Because the pulmonary capillary pressure in most of the lung is greater than the alveolar pressure (page 408), both factors encourage transudation, a tendency checked by the oncotic pressure of the plasma proteins. Thus the surfactant, by reducing surface forces, diminishes one component of the pressure gradient and helps to prevent transudation. Multilayered, less wettable, rafts of surfactant are interspersed with fluid pools. Scarpelli developed different techniques for preparing lung tissue for microscopy. It would therefore be premature to consign the well-established bubble model of alveolar recoil to the history books, but physiologists should be aware that cracks have begun to appear in the longstanding physiological concept. Inset, detail of the surfactant layer showing connection between phospholipid monolayer and bilayer (not to scale). The pressure within an alveolus is always greater than the pressure in the surrounding interstitial tissue except when the volume has been reduced to zero. Airways begin to close at the closing capacity and there is widespread airway closure at residual volume. Otherwise, the oesophageal pressure may be used to indicate the pleural pressure, but there are conceptual and technical difficulties. The alveoli in the upper part of the lung have a larger volume than those in the dependent part, except at total lung capacity. The greater degree of expansion of the alveoli in the upper part results in a greater transmural pressure gradient, which decreases steadily down the lung at approximately 0. At first sight it might be thought that the subatmospheric intrapleural pressure would result in the accumulation of gas evolved from solution in blood and tissues. In fact the total of the partial pressures of gases dissolved in blood, and therefore tissues, is always less than 1 atm (see Table 24. Time Dependence of Pulmonary Elastic Behaviour If an excised lung is rapidly inflated and then held at the new volume, the inflation pressure falls exponentially from its initial value to reach a lower level attained after a few seconds. This also occurs in the intact subject and is readily observed during an inspiratory pause in a patient receiving artificial ventilation (page 30). It is broadly true to say that the volume change divided by the initial change in transmural pressure gradient corresponds to the dynamic compliance, whereas the volume change divided by the ultimate change in transmural pressure gradient. The respiratory frequency has been shown to influence dynamic pulmonary compliance in the normal subject, but frequency dependence is much more pronounced in the presence of pulmonary disease. This resembles the behaviour of perished rubber or polyvinyl chloride, both of which are reluctant to accept deformation under stress but, once deformed, are again reluctant to assume their original shape. Note that inspiratory and expiratory curves form a loop that gets wider the greater the tidal volume. For a particular lung volume, the elastic recoil of the lung during expiration is always less than the distending transmural pressure gradient required during inspiration at the same lung volume. Causes of Time Dependence of Pulmonary Elastic Behaviour There are many possible explanations of the time dependence of pulmonary elastic behaviour, the relative importance of which may vary in different circumstances. If a spring is pulled out to a fixed increase in its length, the resultant tension is maximal at first and then declines exponentially to a constant value. However, if different parts of the lungs have different time constants, the distribution of inspired gas will be dependent on the rate of inflation and redistribution (pendelluft) will occur when inflation is held. These properties give the fast alveolus a shorter time constant and are preferentially filled during a short inflation. This preferential filling of alveoli with low compliance gives an overall higher pulmonary transmural pressure gradient. A slow or sustained inflation permits increased distribution of gas to slow alveoli and tends to distribute gas in accord with the compliance of the different functional units. There should then be a lower overall transmural pressure and no redistribution of gas when inflation is held. Gas redistribution is therefore unlikely to be a major factor in healthy subjects, but it can be important in patients with airways disease. Below a certain lung volume, some alveoli tend to close and only reopen at a greater lung volume and in response to a higher transmural pressure gradient than that at which they closed. The direct relationship between compliance and resistance results in inspired gas preferentially delivered to the stiff alveoli if the rate of inflation is rapid.

Order trimox

In the early 1980s improved immunosuppression led to a resurgence of interest and the technique has now become an established form of treatment bacteria que come carne humana discount trimox 500mg with amex. The function of a transplanted lung is important for the well-being of the recipient, but also furthers our understanding of certain fundamental issues of pulmonary physiology. Clinical Aspects62-64 Indications Patients who are considered for transplant have severe respiratory disease, and are receiving optimal therapy, but still have a life expectancy of less than 2 to 3 years. In recent years the number of donor organs available has remained static while the number of candidates for lung transplants has risen rapidly. Cadaveric donor lungs are taken from patients with limited smoking history and no evidence of lung disease. Strategies to improve the number of lung transplants performed include living-related lobar transplants (see the next section), extending donor selection criteria using more objective tests of lung function or using nonheartbeating donors. With current organ preservation solutions, lung transplants must be performed within 6 to 8 h of organ removal. The donor lung is implanted, with anastomoses of the main bronchus, the left or right pulmonary artery and a ring of left atrium containing both pulmonary veins of one side. Double-lung transplant performed at a single operation is a more complex procedure for which sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass are required. The donor lungs are implanted with anastomoses of either the trachea or both bronchi, the main pulmonary artery and the posterior part of the left atrium containing all four pulmonary veins. A simpler alternative is to transplant two lungs sequentially (termed a double single-lung transplant) through bilateral thoracotomies, and this has now almost completely replaced double-lung transplant. Total cardiopulmonary bypass is, of course, essential and the anastomoses involve the right atrium, the aorta and the trachea. Single-lung transplantation is favoured, partly because mortality may be lower following this operation, but also because each suitable donor can be used to transplant two recipients. The same selection criteria apply as for cadaveric transplantation, thus patients with cystic fibrosis must have bilateral transplants and therefore two related donors. Survival figures are at least comparable with other forms of lung transplantation, and evidence is emerging of better survival in paediatric lung transplants when living-related, rather than cadaveric, organs are used. Outcome Following Transplant Given the nature of the surgery it is not surprising that there is significant perioperative and early postoperative mortality. Thereafter, mortality rates are low when consideration is given to the 2-year predicted survival of recipients before transplant, and half of patients now survive at least 6 years. These improvements in ventilatory performance contribute to the huge improvement in quality of life following lung transplant. Exercise performance depends on many factors, which, in addition to pulmonary function, include circulation, condition of the voluntary muscles, motivation and freedom from pain on exertion. Improvement in performance does occur following lung transplantation, but exercise limitation remains common, with maximal oxygen uptake (page 228) of about half of normal. There is no evidence that this limitation results from poor pulmonary function, and a muscular origin is more likely,70 possibly related to myopathy induced by immunosuppressant drugs. Treatment involves escalation of immunosuppressive therapy and supportive management as for other forms of lung injury. Recovery of the transplanted lung may occur, but mortality from acute rejection is high. Chronic rejection in the lung manifests itself as obliterative bronchiolitis syndrome, the origin of which is not clear but which occurs in up to half of patients by 5 years posttransplant. Both conditions feature arterial hypoxaemia, pyrexia, leucocytosis, dyspnoea and reduced exercise capacity. Physiological Effects of Lung Transplant Transplantation inevitably disrupts the nerve supply, lymphatics and the bronchial circulation. The condition of the recipient is further compromised by immunosuppressive therapy. Denervated Lung the transplanted lung has no afferent or efferent innervation and there is no evidence that reinnervation occurs in patients. It was therefore expected that denervation of the lung, with block of pulmonary baroreceptor input to the medulla, would have minimal effect on the respiratory rhythm. This is in contrast to the dog and most other laboratory animals, in which vagal block is known to cause slow deep breathing. Bilateral vagal block in human volunteers was already known to leave the respiratory rhythm virtually unchanged, and it was therefore no great surprise when it was shown that bilateral lung transplant had no significant effect on 32 Pulmonary Surgery 493 the respiratory rate and rhythm in patients, after the early postoperative period. The cough reflex, in response to afferents arising from below the level of the tracheal or bronchial anastomosis, is permanently lost after lung transplantation. Similarly, a bilateral single-lung transplant will be preferable to a double-lung transplant, because the potent carinal cough reflex remains intact. The abnormality in cough reflex is a major contributor to lung infection following transplant, along with altered mucous clearance as described later. During exercise in patients with a single-lung transplant, the already high blood flow to the transplanted lung does not seem to increase further, and the normal recruitment of apical pulmonary capillaries (page 93) cannot be demonstrated. This, together with the absent cough reflex below the line of the airway anastomosis, means that the patient is at a disadvantage in clearing secretions. Side effects of immunosuppression compound these changes and lead to enhanced susceptibility to infection of the transplanted lung. Though these factors clearly do not preclude long-term survival of the graft, one-quarter of deaths following lung transplantation result from infection. British Thoracic Society guideline for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy in adults. Alterations in pulmonary mechanics and gas exchange during routine fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy: a standardized approach to therapy for hyperhidrosis. The effect of standard posterolateral versus muscle- sparing thoracotomy on multiple parameters. Respiratory muscle strength after lung resection with special reference to age and procedures of thoracotomy. Treatment of complicated spontaneous pneumothorax by simple talc pleurodesis under thoracoscopy and local anaesthesia. Bronchial blocker lung collapse technique: nitrous oxide for facilitating lung collapse during one-lung ventilation with a bronchial blocker. Hypoxaemia associated with one-lung anaesthesia: new discoveries in ventilation and perfusion. Effects of propofol vs sevoflurane on arterial oxygenation during one-lung ventilation. Effects of thoracic epidural anaesthesia on pulmonary venous admixture and oxygenation during one-lung ventilation. Effect of thoracic epidural anesthesia with different concentrations of ropivacaine on arterial oxygenation during one-lung ventilation. Inhaled nitric oxide administration during one-lung ventilation in patients undergoing thoracic surgery. Reducing tidal volume and increasing positive end-expiratory pressure with constant plateau pressure during one-lung ventilation: effect on oxygenation. Setting individualized positive end-expiratory pressure level with a positive end-expiratory pressure decrement trial after a recruitment maneuver improves oxygenation and lung mechanics during one-lung ventilation. Does a protective ventilation strategy reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after lung cancer surgery Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation of lung cancer patients: a review of the literature. Neoalveolarisation contributes to compensatory lung growth following pneumonectomy in mice. Intraoperative tidal volume as a risk factor for respiratory failure after pneumonectomy. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 10: bullectomy, lung volume reduction surgery, and transplantation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A randomized clinical trial of lung volume reduction surgery versus best medical care for patients with advanced emphysema: a two-year study from Canada. Changes in arterial oxygenation and self-reported oxygen use after lung volume reduction surgery. Computed tomography predictors of response to endobronchial valve lung reduction treatment.

Discount trimox line

The high incidence of respiratory complications in this group makes them an ideal study population antibiotics for acne prone skin buy 500 mg trimox visa, but there remains little information regarding the respiratory effects of perioperative smoking and more minor surgery. Nicotine, which is responsible for many untoward cardiovascular changes, has a half-life of only 30 minutes, whereas carboxyhaemoglobin has a half-life of 4 hours when breathing air. A smoking fast of just a few hours will therefore effectively remove the risks associated with carbon monoxide and nicotine. Other studies have failed to demonstrate this effect, and there are concerns that the original investigations had insufficient statistical power to conclusively prove a benefit to continuing to smoke 19 Smoking and Air Pollution 285 before major surgery. In the longer term these effects are likely to be mediated by changes in gene expression by the airway and even quite low-level smoke exposure, as seen with passive smoking, causes changes in the expression of 128 different genes with a host of physiological roles. Evidence of in vivo oxidative stress in smokers is based mainly on measures of antioxidant activity in both the lungs and blood. Compared with nonsmokers, human smokers have reduced levels of vitamin E in alveolar fluid, reduced plasma concentrations of vitamin C and greatly increased superoxide dismutase and catalase activity in alveolar macrophages. There are two groups of compounds with carcinogenic activity, found mostly in the tar of the particulate phase. Tobacco-related nitrosamines and nicotine derivatives are also carcinogenic, and, because of their ease of absorption into the blood, are responsible for cancer formation not only in the respiratory tract and oesophagus but also in more distant organs such as the pancreas. Knowledge about these carcinogens has led to many attempts to reduce their concentration in smoke by modifying the cigarette, and tar levels in cigarettes have declined almost threefold since 1955. However, these changes have had little impact on the incidence of lung cancer (page 426), and smoking cessation remains the best way to avoid all smoking-related cancers. Oxidative Injury29 There is compelling evidence that oxidative injury, including peroxidation of membrane lipids, is an important component of the pulmonary damage caused by cigarette smoke. These effects are likely to be mediated by upregulation of the genes for phospholipase A2 and various peroxidase enzymes. Cell-Mediated Oxidative Damage this results from smoking-induced activation of, or enhancement of, neutrophil and macrophage activity in the respiratory tract. This suggests that the interaction of particulate matter and alveolar macrophages releases a neutrophil chemoattractant, and that neutrophils are subsequently activated to release either proteases or reactive oxygen species. This activation may be a direct response to cigarette smoke or may Immunological Activation31 Smokers have elevated serum IgE levels compared with nonsmokers, the cause of which is uncertain but may be twofold. Direct toxicity and oxidative cell damage result in greater airway mucosal cell permeability, allowing better access for allergens to underlying immunologically active cells. Smoking also increases the activity of some T-lymphocyte subsets that are responsible for producing interleukin-4, a cytokine well known for stimulating IgE production, and is known to produce a long-term systemic inflammatory response. In spite of these controls, increased overall energy requirements and the internal combustion engine have ensured that air pollution remains a current problem. At the same time as levels of pollutants have been reduced in many parts of the world evidence of their harmful effects on health has increased, and air pollution remains a global problem. Air pollution is associated with a greater prevalence of cardiac disease,35 incidence of lung cancer36 and an increased natural-cause mortality,37 though a link with nonmalignant respiratory mortality remains unproven. However, particulates and nitrogen oxides are invariably produced, and this remains a source of sulphur dioxide. Secondary pollutants are formed in the atmosphere from chemical changes to primary pollutants. Because in still conditions mixing of air masses is slow to occur, the relatively cold air sits on top of the warm air below. Respiratory Effects of Pollutants32 Recommended maximum levels of common pollutants are shown in Table 19. The extent to which these levels are achieved varies greatly between different countries and from year to year. Petrol engines that ignite the fuel in an oxygen-restricted environment produce varying quantities of carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons such as benzene and polycyclic aromatic compounds. Ozone is a secondary pollutant formed by the action of sunlight on nitrogen oxides, and therefore highest levels tend to occur in rural areas downwind from cities and roads. In all areas, the dependence on sunlight means that ozone levels slowly increase throughout the day reaching peak levels shortly after the evening rush hour. Ozone is toxic to the respiratory tract, with effects dependent on both concentration and duration of exposure. This variability in response is partly a result of differing genetic susceptibility. Even so, there is good evidence that high ozone concentrations are associated with increased hospital attendance and respiratory problems, particularly in children. Normal atmospheric levels have no short-term effect on healthy subjects, but asthmatic patients may develop bronchoconstriction at between 100 and 250 parts per billion. Particulate matter consists of a mixture of soot, liquid droplets, recondensed metallic vapours and organic debris. The disparate nature of particulate pollution reflects its extremely varied origins, but in the urban environment, diesel engines are a major source. Their small size means they should be breathed in and out without being trapped by the airway lining fluid (page 206). However, some particles are retained in the lung, where they remain in the long term, probably contained within macrophages, and without any evidence of systemic absorption. Indoor air quality generally reflects that of the outdoor air except that ozone levels are invariably low indoors due to the rapid reaction of ozone with the synthetic materials that make up much of the indoor environment. In addition to pollutants from outside, there are three specific indoor pollutants. Allergens Warm moist air, poor ventilation and extensive floor coverings provide ideal conditions for house dust mite infestation and the retention of numerous other allergens. This is believed to contribute to the recent upsurge in the prevalence of atopic diseases such as asthma, and is discussed in Chapter 27. Smokers, who have permanently elevated carboxyhaemoglobin levels, appear to be resistant to these symptoms. However, long-term exposure does seem to be clinically significant by, for example, causing worsening of asthma symptoms in children. Indoor Air Pollution56 Worldwide, the most common form of indoor air pollution is smoke produced by fires used for cooking, leading to calls for improved cook stoves to reduce the use of indoor open fires. As for the outdoor pollution described earlier these pollutants are associated with the development of many respiratory problems,58 including respiratory infections in children. This has led to dramatic changes in indoor air quality, including warmer temperatures, higher humidity levels and reduced ventilation. The respiratory effects of passive smoking were described earlier (page 283), and 19 Smoking and Air Pollution 2. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross-sectional population study. Expression of genes involved in oxidative stress responses in airway epithelial cells of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Adverse effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on innate immunity in infants. Perioperative respiratory events in smokers and nonsmokers undergoing general anaesthesia. The effect of passive smoking on the incidence of airway complications in children undergoing general anaesthesia. Smoking cessation reduces postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Threshold of biologic responses of the small airway epithelium to low levels of tobacco smoke. Focus on antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant strategies in smoking related airway diseases. Air pollution as a carcinogen further strengthens the rationale for accelerating progress towards a low carbon economy. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Association of indoor nitrogen dioxide exposure with respiratory symptoms in children with asthma. There are more than a billion smokers worldwide, a third of whom will die as a result of smoking. How much of these is inhaled depends on the number of cigarettes smoked, make-up of the cigarette. The airway changes and reflex bronchoconstriction lead to airway narrowing and closure, disturbing ventilation perfusion relationships. These changes affect lung volumes, which decline more quickly throughout life in smokers.

Cheap trimox 250 mg otc

Horses are obligate nasal breathers with an upper respiratory tract poorly designed for extreme exercise oral antibiotics for dogs hot spots purchase 500 mg trimox. Despite these efficient physiological responses, hypoxia and hypercapnia during exercise do occur in racehorses and are only rarely seen in humans (page 233). Compared with humans exercise hyperventilation in horses does not fully match the metabolic requirement of the muscles, and this contributes to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Hyperventilation relative to exercise performed is greater in ponies, and hypoxia and hypercapnia during exercise less common, though of course their exercise capacity is much less. This indicates that of the various physiological changes developed in racehorses, the ability of the muscles to consume oxygen has outstripped the capacity of the cardiorespiratory system to deliver it. During times of metabolic stress, including severe exercise, horses increase their haematocrit by mobilizing their huge splenic reserves of blood, in some cases doubling haematocrit and oxygen delivery. Diving Mammals Diving mammals rely on breath holding for dives and have multiple adaptations that permit remarkably long times under water and the attainment of great depths. Such feats depend on a variety of biochemical, cardiovascular and respiratory adaptations. For most diving mammals complete alveolar collapse is believed to occur at depths between 30 and 100 m,43 effectively stopping gas exchange and preventing the development of high partial pressures of nitrogen in the lung. This complete collapse is only possible because of extremely compliant chest wall and alveoli and relatively rigid airways, allowing air to move from the alveoli into the airway as the animal dives. This structure has evolved to minimize the risk of developing widespread pulmonary infection with the septa acting as physical barriers to prevent infection spreading between lobes. The total alveolar surface area and alveolar capillary density of the ruminant lung is small compared with other domestic mammals of a similar size. Although the lungs are sufficient to provide the basic metabolic requirements, ruminants have a limited respiratory reserve which is accommodated by having a generally sedentary lifestyle. The diffuse pulmonary oedema which occurs in many bovine diseases results in oedematous enlargement of the septa leading to further restriction of the remaining functional lung parenchyma. Bacterial colonization leads to a diffuse acute pleuropneumonia, obliterating functional lung tissue and impairing gas exchange in the same way as in humans. It is also accepted that the development of severe respiratory disease in young cattle reduces their productivity in later life through reduced longevity, increased time taken to produce a calf and increased mortality, all of which have economic impact. The resulting cellular damage is similar to that seen with pulmonary oxygen toxicity in other mammals, with damage to type 1 alveolar epithelial cells and later in the process proliferation of type 2 epithelial cells (page 351). The interstitial oedema increases the thickness of the interlobular septa causing compression of the nearby parenchymal tissue, limiting the area available for gas exchange. The clinical presentation of these pathological changes can be severe, and even the effort required to move cattle off the affected pasture can cause a further decline in lung function and gas exchange leading to sudden death. Vena Caval Thrombosis Lung disease as a result of venous embolization occurs in cattle, illustrating the role of the lung as a circulation filter (page 203). Caval thromboses are most commonly observed in the caudal vena cava but can also originate in the cranial vena cava. A common cause of septic emboli is rupture of a hepatic abscess directly into the caudal vena cava, but they can also develop by haematogenous spread from infection within the 25 Comparative Respiratory Physiology 373 hoof, udder or uterus in adults,51 or an infected umbilicus in calves. Pulmonary abscesses occur early in the disease process, and due to the distinct lobular nature of the bovine lung may be associated with few clinical signs as the infection remains contained within one lobe. As more regions of lung become involved through the dissemination of further emboli, respiratory distress is observed due to the loss of more lung parenchyma. This makes the equids susceptible to more widespread lung disease than seen in ruminants. Although it can occur in any horse it is more often reported and investigated in racing animals due to the effect on their performance when racing. It is normally diagnosed by direct observation using an endoscope while the horse exercises. Laryngeal paralysis and hemiplegia are insidious in onset and cause a slow but progressive obstruction leading to gradually worsening exercise hypercapnia. This leads to impaired exercise performance and progressively worsening exercise-induced hypoxaemia, although hypercapnia does not seem to be exacerbated. In maximally exercising horses the pressure within the pulmonary arteries and capillaries can reach levels close to 80 to 100 mm Hg. These changes may be compounded in racing horses by vascular remodelling of pulmonary veins occurring predominantly in the caudodorsal lung region. The most likely explanation is the unique combination in an exercising horse of a huge cardiac output associated with very low intrathoracic pressures due to their susceptibility to airway obstruction. Evolution of vertebrate haemoglobins: Histidine side chains, specific buffer value and Bohr effect. Historical reconstructions of evolving physiological complexity: O2 secretion in the eye and swimbladder of fishes. Oxygen binding properties, capillary densities and heart weights in high altitude camelids. Comparative physiology of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension: historical clues from brisket disease. Right ventricular hypertrophy with heart failure in Holstein heifers at elevation of 1,600 meters. Maximum O2 uptake, O2 debt and deficit, and muscle metabolites in Thoroughbred horses. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses in Thoroughbred horses during treadmill exercise. Tracheal compression delays alveolar collapse during deep diving in marine mammals. The evolution of a physiological system: the pulmonary surfactant system in diving mammals. Comparative respiratory strategies of subterranean and fossorial octodontid rodents to cope with hypoxic and hypercapnic atmospheres. Recent advances and trends in the comparative morphometry of vertebrate gas exchange organs. Development, structure, and function of a novel respiratory organ, the lung-air sac system of birds: to go where no other vertebrate has gone. Local control of pulmonary blood flow and lung structure in reptiles: Implications for ventilation perfusion matching. Association of 3-methyleneindolenine, a toxic metabolite of 3-methylindole, with acute interstitial pneumonia in feedlot cattle. Putative mechanisms of toxicity of 3-methylindole: from free radical to pneumotoxicosis. Coughing in thoroughbred racehorses: risk factors and tracheal endoscopic and cytological findings. Lung region and racing affect mechanical properties of equine pulmonary microvasculature. Ultimately all these systems involve providing a large enough area of a thin diffusion barrier across which gases can diffuse. For more complex systems, the way in which the respiratory gases come into contact with blood is crucial to efficiency with tidal breathing (mammals) much less efficient than a countercurrent system (birds and fish). Homeothermic (warm-blooded) animals require much greater respiratory activity then ectothermic (coldblooded) animals to obtain the large amount of oxygen needed to keep warm. In land-dwelling molluscs (slugs and snails) the mantle is filled with air to supplement integumental gas exchange. Gas movement along the tracheae and into the tissues is by diffusion and limits the size to which these animals can grow. Another disadvantage is loss of water vapour which is minimized by spiracles on the body surface controlling the amount of air gaining access to the tracheae. By using air sacs to ventilate the lung during both inspiration and expiration birds can have a lung which does not need to expand and contract with breathing. As a result the lung-diffusion barrier is thin and its perfusion arranged in such a way to form a countercurrent system. Pulmonary venous blood gas levels are close to those of inspired gas, which allows birds to fly at high altitude. Amphibians and reptiles have a dual circulation with separate systemic and pulmonary circulations, but most have a single ventricle and changes in pulmonary vascular resistance control the relative distribution of flow to the two circulations. Fish have a single circulation with the gills in series with the other organs exposing them to higher pressures requiring greater strength and a thicker diffusion barrier than lungs. Haemerythrin contains a protein-bound iron found in some marine animals which can store oxygen for up to 2 h.